Suppose you have a test for a rare condition that affects one person in a million. If you test a million people, you will, on average, find one person with the condition. However, if the test is 99% accurate (which is very good!) then 1% of the results will be wrong and you'll get 10,000 false positive results. This means that if you're one of the people who get a positive result, there's only one chance in 10,001 that you actually have the rare condition.

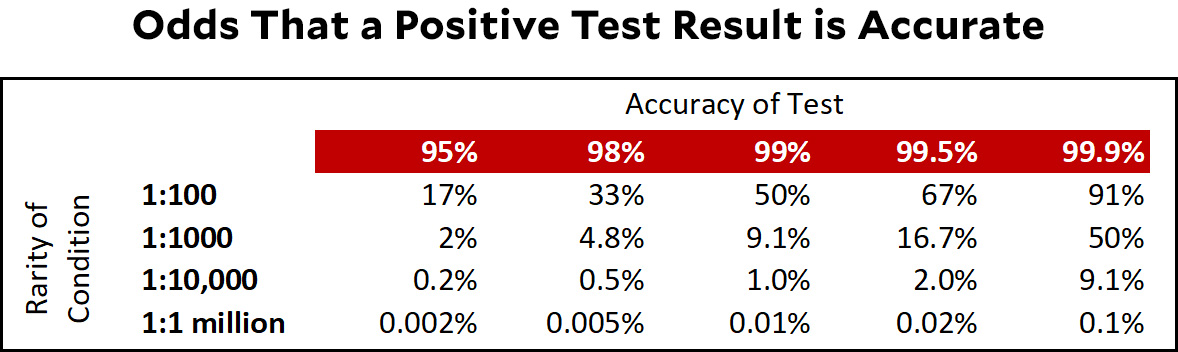

This is called the base rate problem and it's nothing more than simple arithmetic. It depends solely on the accuracy of the test and the rarity of the condition. Here's a quickie table that shows how likely it is that a positive result is actually correct under different circumstances:

With this in mind, you might want to read a piece in today's New York Times, "When They Warn of Rare Disorders, These Prenatal Tests Are Usually Wrong." Just keep in mind that nothing in it is really the result of an "investigation" and none of it has to do with poorly performing tests. The whole thing is purely mathematical and anybody with even a modest mathematical background was aware of it all along.

With this in mind, you might want to read a piece in today's New York Times, "When They Warn of Rare Disorders, These Prenatal Tests Are Usually Wrong." Just keep in mind that nothing in it is really the result of an "investigation" and none of it has to do with poorly performing tests. The whole thing is purely mathematical and anybody with even a modest mathematical background was aware of it all along.

POSTSCRIPT: I should clarify something. When I say "anybody with even a modest mathematical background was aware of it all along," by anybody I mean the scientists at the test companies—and, therefore, everyone else at the test companies too. They have no excuse for not being clear about this all along.

So the story is "reporter and public encounter math, become frightened"?

I think the story is rather, “reporter tries to explain math to public who are generally unaware, and are frightened by things they don’t understand.”

No. The reporter was egregiously innumerate.

He also clearly did not understand that when you are talking about a devastating genetic condition, it is extremely valuable to be told "Your baby has a 5% chance of having this condition instead of a .001% chance like most babies. You can use another more expensive test that might cause a miscarriage to either rule out or confirm this possibility."

Sorry, Michael, I thought Lounsbury was referring to Kevin drum and his story.

In either case, unfortunately, hoping the general public will understand conditional probabilities, let alone Bayesian calculations, is whistling in the wind.

The NYT reporter was claiming that the testing companies have been essentially representing the chance of having the disease as 100% giving no information about the true probability. Doctors also may not have been informing patients about the likelihood of a false positive. There are also other questions about the reliability of the evidence for the tests.

It isn't just the general public. I've had to explain MTBF (mean time between failure) calculations to senior SW engineers. Many of them get suicidal (metaphorically) at the way complex processes and equipment inexorably go to hell as the number of components go up. Economics isn't the only "dismal science".

Hardware engineers are much tougher minded, and can resolve their frustrations more satisfactorily with a large enough sledgehammer be fore going back to the drawing board.

Yes.

And this is also the problem with much of the scary stories and reporting on both vaccine risks and covid risks re things like long covid .

The issue is not really just the small % age of actual cases. It is also the number of false test results being too high in comparison The issue is really just that the false test % age is far higher than the true occurrence percentage . And that can be the case if the true percentage is very very low even if the false test percentage is also low but just not as low as kevin illustrates. But same sort of issue in reverse if you treat the test as whether someone does NOT have a condition and the true occurrence of that condition is very high. Note that, in Kevin's pre natal example , the opposite affects occurs on the other direction. If you get a negative test result, then the chance that the condition really exists but the negative test result is wrong is vanishly small given that the actual occurrence is so small. Two sides to this coin in every case.

Consider the anecdotal reports of people dropping dead unexpectedly within a few days of being vaccinated when seemed in good health and think of that report as a " test " of whether someone's death is caused by the vaccine. I.e does dying within a few days of the vaccine mean the death is caused by the vaccine? Well that " test " is also highly accurate because in the overwhelming number of cases the person does not die within a few days anyway and dies years later. And all those negative tests results are 100% accurate . And there are a few sudden deaths of healthy people who drop dead suddenly for no apparent reason every month . So, when millions of people are getting vaccinated that month , expected that a few will drop dead soon after vaccination just by chance.

But consider long covid and consider the " test " to be having one of the long list of possible symptoms within 6 months of covid illness. But think of it as testing for NOT having long covid, not having it. That test may be highly accurate too if very few have long covid but the list of symptoms is so extensive that almost anyone has one of them in a 6 month period. The true percentage of not having those symptoms is so small that it overwhelms the number who are actually having those symptoms due to long covid . Thus the reports of long covid can be greatly inflated if you use as evidence just having such a lengthy list of common symptoms

The biggest problem with the NYT article is that it made it sound like these tests were all useless, since they had pretty bad positive predictive value (the chance that a positive result means you have the problem).

But the key takeaway is that these are useful screening tests because they have very high negative predictive value -- if you test negative, you almost certainly don't have the condition, which can save you the (slightly) more dangerous CVS procedure. But they are screening tests, which in this case means that since the PPV is only something like 10%-30%, you're probably negative even if you test positive and will definitely need a real test (amnio or CVS) in that case.

Still, these tests might cut out 90% or more of the need for amnio / CVS.

The main issue seems to be that doctors are unaware of or don't understand this basic math, or aren't advising their patients about it. This is the real problem :

> 14 patients who got false positives... Eight said they never received any information about the possibility of a false positive, and five recalled that their doctor treated the test results as definitive.

I mean I do stats professionally but if my doc told me I had X, I'm not immediately redoing the probability calculations myself, and it's crazy to expect patients to. In fairness though even practicing doctors, really, shouldn't have to do this themselves... It should be made clear on the test label that it's a preliminary test that may indicate follow-up, not a definitive test.

fyi:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/jan/02/2021-year-when-interpreting-covid-statistics-crucial-to-reach-truth

This is true but incomplete. The easy solution is to retest positives: The probability of getting two false positives in a row does not depend on the scarcity of the condition. It depends solely on the accuracy of the test. To be safe you'd want to use a different test for confirmation if available.

If the false-positive rate is 10% (i.e. 90% accuracy) the probability of having a two false positives in a row is 1%, if 1% (99% accuracy) it is 0.01%.

The problem is actually more complicated because these tests also miss some cases; they produce false negative results. Which is a problem in the case of communicable diseases: Some people walk around infectious yet confident that they are not.

BTW a good example for a test where that becomes a problem is PSA: If the test is positive it means you MAY have prostate cancer. If it is negative you may still have it. Either way the majority of cases do not need much care as they grow so slowly that you are still going to die from something else.

Do false positives occur randomly, or will repeating the test on the same person likely produce the same result, even if it's false?

One issue with mass use of screening tests is that they scare the bejesus out of people. But one compounding issue is the way the results are presented to patients.

When my daughter was pregnant for the first time, she was told that there was a 1 in 500 chance that her baby had some awful birth defect. She didn’t like those odds at all! I then told her that this meant was that was a 99.8% chance her child did NOT have that condition, and she liked those odds a lot better! (She’s very numerate and understands statistics.)

Drum’s final line (“… anybody with even a modest mathematical background was aware of it all along”) is unfair. As has been pointed out by others, when we’re faced with some potentially terrible medical news, our inner statistician goes away, to be replaced by the reptilian monster within shouting, “OMG, I’M GOING TO DIE!!!”

Journalists were promised there wouldn’t be any math when they chose to go into J school. It actually was a reason cited often by my friends at my alma mater when I asked why they wanted to go into a (even back then) dying career.

The New York Times story is mainly about making people aware that false positives happen and that screening for very rare disorders might not be a good idea if there is no particular reason to suspect one of these disorders. Anyway, doctors should make sure patients understand the low predictive power of some tests, and the need for more invasive testing to confirm a positive result.

"[A]nybody with even a modest mathematical background" does not include most Times reporters or readers, most patients, including pregnant women, and probably not most doctors (although it medicine is considered a STEM field, the doctors I know are not particularly numerate). So I don't really take the point of Kevin's criticism.

The issue / story here isn't the base rate problem, but the fact that these tests are being done and marketed seemingly without enough (any?) disclosures or safeguards. I do stats for a living and recently had a test like this done, and had they come back with a positive result I would have assumed they had taken the base rate into account when reporting it to me. After all, when you get a cancer screening and it shows results, they don't call you and say "you 99% have cancer!" -- they say "we need to do some more tests" for precisely this reason.

when the tests are wrong, are they systemically wrong, or randomly wrong?

If we give the test 10 times at once, do we now have a test that is 20 9's accurate? Or is it still just 99% accurate?

I'm in the camp that the *story* is good, because most Americans are innumerate. According to the article, the companies advertise their findings as "reliable" and "highly accurate," offering "total confidence" and "peace of mind." Even if some of those are technically true, in context, they're highly misleading. I'm not even sure the "total confidence" one is technically true, because you cannot, after taking this test, have "total confidence" that your fetus has one of the conditions.

The article also says that 6 percent of patients who get this test get an abortion without a confirmation test. Presumably, you wouldn't spend money on this test in the first place if you were already planning to get an abortion. So, regardless of what you think about abortion, the test is resulting in a lot of terminations of *wanted* pregnancies that may be perfectly healthy.

I read the NYT report more as a warning that doctors are doing a very poor job of explaining the test results and what they main probably because the test companies are making unfonded claims and doctors are not particularly numerate.

Yeah, this was my takeaway. The testing companies were implying that the tests were completely accurate to drive sales.

I also think the NYT article is, on net, a positive contribution. The more prospective parents understand that a positive test result does not mean their baby will definitely have a problem, the better. It also, contra Kevin, did involve more work than just noticing that lots of people don't understand prior probability: the false positive rates of these tests had to be estimated via a rudimentary meta-analysis, not read off of a datasheet.

It doesn't do a very good job, however, of clearly laying out the statistical concepts. It retains everyday definitions of terms like accuracy (which isn't even used consistently between specialists) and reliability while hinting at the complexity these definitions mask, without introducing the technical terminology required to present the complexity precisely (sensitivity, specificity, base rate).

On the other hand, it's really hard to explain statistical concepts in words (as innumerable word-salad Methods sections will attest), and it's even harder when the audience ranges from professional statisticians to people who haven't ever had to learn probability.

I think the article does a decent job of trying to discuss a real problem resulting from a complicated reality without turning into a stats lesson. You might say "well, but people need a stats lesson," and I might even agree, but good luck getting them to sit still or keep reading through one.

So I'm not surprised stats-savvy folks have been lambasting it, but I also think the criticisms are mostly missing the point of the article, which is **not** to provide a lesson in Bayesian inference. It's to say, as persuasively as possible, "if you thought this thing, think again, and seek out competent advice, because the testing companies won't explain it to you and your doctor will generally be unable to do so either."

Doctors are not always equipped to handle the base rate fallacy and screening tests for conditions that are only somewhat rare. Atul Gawande wrote about too many cancer screenings as more or less the same problem back in 2015- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/05/11/overkill-atul-gawande

Slightly different in that those screenings are picking up something that's there just unlikely to cause harm but in both cases it's a test is picking up a false positive from the patient's perspective. And in both cases generally requires at least a much more invasive test as follow up where without the screening that wouldn't be necessary. But on the other hand the screening tests in either case can be incredibly useful if there is a medical reason to suspect the person actually has an increased risk for the condition. That's a consistent problem in the US, getting the right people the appropriate care, but not having the companies that make that product try to sell it to 10 or 100 times that number of people.