Remember the Great Resignation? Fed economist Bart Hobijn says there's nothing to it:

The labor market recovery since the depth of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020 has been the fastest in postwar history....At the same time, the share of workers quitting their jobs—either to take new jobs or to exit the labor force—has also hit its highest level since 2000, when the data began being collected.

This recent spike in quits has been referred to as the “Great Resignation.” Some have interpreted it as a wave of resignations, driven by people reconsidering their career prospects and work-life balance, that is drastically altering the labor supply. In this Economic Letter, I provide two pieces of evidence that cast doubt on this narrative and, instead, suggest that the high rate of quits is simply a reflection of the rapid pace of overall labor market recovery.

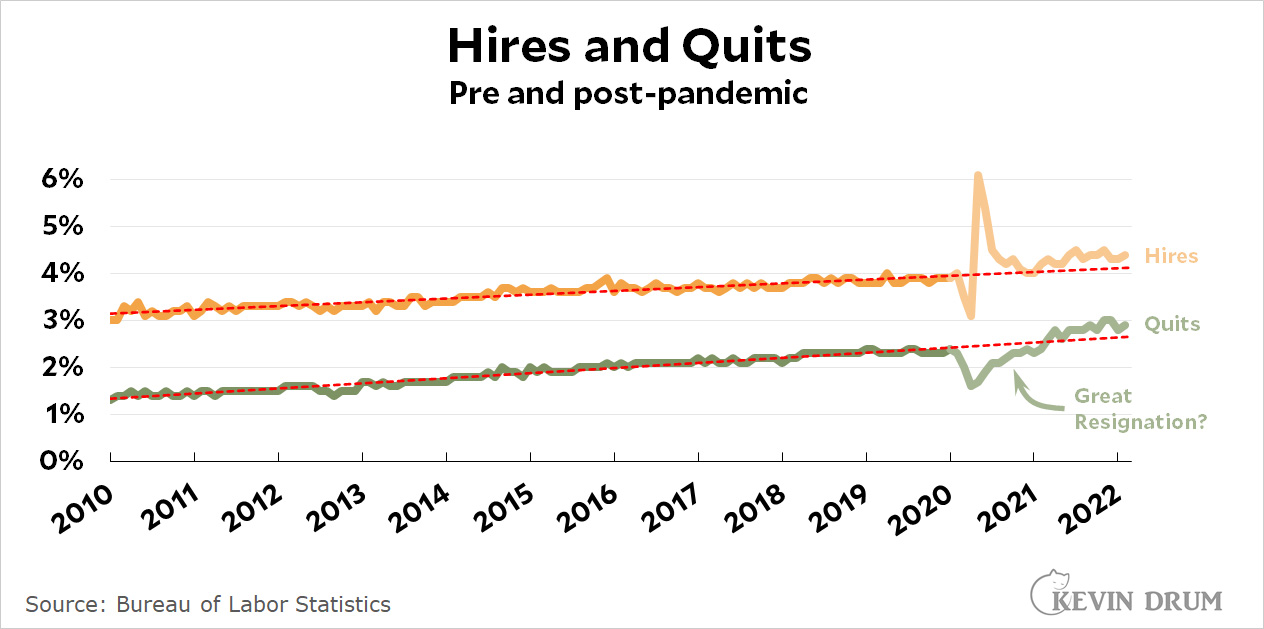

Go ahead and read Hobijn's piece for the details, but I continue to wonder where this narrative ever came from in the first place. For starters, here's the rate of both hires and quits during the Great Recovery of the past decade:

The quit rate dropped precipitously at the start of the pandemic for obvious reasons: workers were being laid off by the millions and no one in their right mind wanted to enter a job market like that.

The quit rate dropped precipitously at the start of the pandemic for obvious reasons: workers were being laid off by the millions and no one in their right mind wanted to enter a job market like that.

But that turned around shortly and the quit rate went back up. Critically, though, the quit rate merely rebounded to its old Great Recovery trendline. It may be that 3% is a "record" quit rate, but it's only very slightly above trend. Plus there's this:

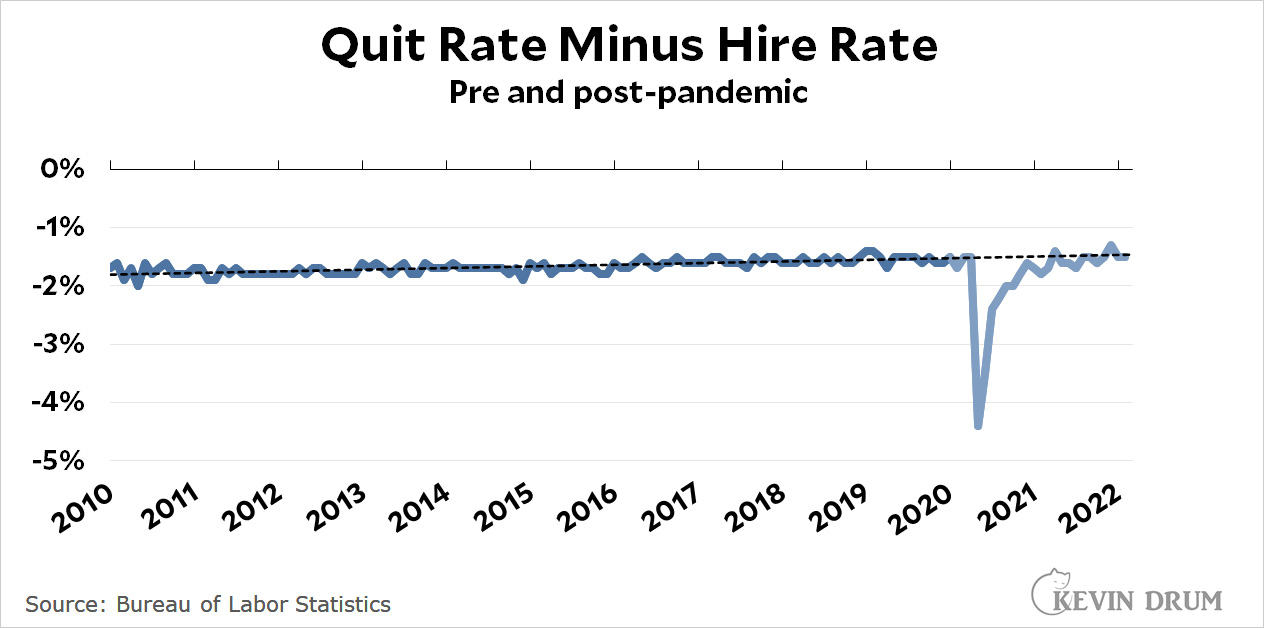

This chart shows the difference between the hire rate and the quit rate. As you can see, it's very, very stable. The quit rate during the Great Recovery has been consistently about two percentage points below the hire rate.

This chart shows the difference between the hire rate and the quit rate. As you can see, it's very, very stable. The quit rate during the Great Recovery has been consistently about two percentage points below the hire rate.

Bottom line: There was never really anything to the Great Resignation theory. Quits and hires spiked and rebounded during the pandemic year of 2020 but were back to normal by the start of 2021. I'm not sure why you need anything more than this to understand what was going on.

The media tends to get fixated on a narrative framework, and then it takes a lot of time and effort to push them off that framework - especially if it complies with their ideological prior beliefs (we still get tons of folks thinking everything is turning into the "gig economy"). "Great Resignation" got there early, and then stuck around.

I have a theory....

In April/May 2020, a bunch of marginal restaurants, especially in urban areas, closed shop. A lot of others had to scramble to stay afloat, and folks working restaurant work tend to not have much buffer, so the food service labor market was scrambled for a while.

This happened right as lots of white-collar folks were getting used to working at home, and ordering food delivery a lot, because they couldn't do a lot of other self-comforting activities. So they noticed restaurant failures and staff issues, and decided the whole economy was doing the same.

Then you get three journalists swapping hot takes on Twitter, and your next 12 weeks of business columns are all set but for the writing.

Funny. But also sad at how plausible an explanation that it.

Not only plausible, but probable (abstracting away from the particular details to the overall narrow personal experience supported by self-reinforcing circle of exchanges and illustrated by ad-hoc anectdote-as-date).

The profound innumeracy of journalists makes the profession structurally bad at covering this specific kind of subject. One should generally distrust and discard the early takes on any social trend where the reporting is not derived from actual statistics - regardless if one feels it may be true or not.

Yeah, the stories came out way ahead of any reliable data and were too appealing to revise.

The real quit rate to watch is retiring baby boomers. Baby boomers were big cohort, and coming on the heels of a Depression baby bust they left a job vacuum behind them. Now, they're retiring, and companies have to reopen their hiring pipelines. Local examples include Alaska Air with its pilot shortage and the Washington State Ferry system which is now runny a janky schedule.

And they'll be drawing down their 401K's...so less money in stock market?

Alas, I can find averages for age cohorts, but not total amounts (nor do I know if "average" is an average of those with 401K's or total in 401K's over total population in cohort).

Plus, more than a million people died, and presumably at least some of them were workers. Do they show up as quits?

Nope.

Most of the million were old, long retired, or with a disability. No, it was not a effect.

Asserted with no source to back it up. Lots of elderly people still are workers, thanks to the insufficiency of Social Security combined with lack of savings/pensions. And lots of non-seniors have died too, 250k or so according to this site. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1191568/reported-deaths-from-covid-by-age-us/

Also, fck off troll.

Do not feed the troll.

It is ironic your reply to the troll about assertion contains its own unsupported ideological assertion ('lots of elderly are workers, thanks to insufficiency of...").

Of course 250k non-seniors is, in a pool of 350+ millions population, essentially a non factor.

Ironically the Troll's comment is probably largely accurate from an overall statistical PoV (although any accuracy on his part is accidental).

Talks amongst yourselves, I'm feeling verklempt....

Alot of people were like my sister: Pickier about what job they picked next, holding onto the last one until they were laid off, then picking back up with one that met their expectations.

Who knew there was a way to be out of work in food service, teaching, and theater at the same time?

The Quits vs Hires chart from thr Fed website (link below) certainly makes both the level and rate of change look dramatically different than the chart that Kevin posted.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=NVo3

The next chart (link below) is indexed to the start of the Covid recession and shows how Quits and Hires have changed since Covid appeared. This chart certainly gives the impression that something dramatic happened and its hard to wave it off as a narrative gone astray.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=NVoD

Yes, I would like to hear Kevin address the discrepancies here. Is it or is it not true that month after month set a record for the number of people who left their jobs?

Bbbbut, it must have been real, Mother Jones said so and even made it "The Big Feature" of their January/February 2022 issue: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2022/01/record-quits-great-resignation-labor-workers-pandemic/ ...

Here is something missing from thr Great Resignation analysis.

Look at the change in 'People not in the labor force':

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=NVpI

Thats dramatic and it hasn't fully resolved itself like the Fed paper and Kevin's post would imply. Quits rose dramatically as did 'People not in the labor force'.

Using only Hires and Quits is obviously missing something....layoffs are missing and likely alot of those hires are people who were laid off, not just people who quit. Not sure how to determine how many Quits are out of the labor force.

I believed the narrative only because of what was happening around me. I’m stuck in a job that pays so so and is one of those bottom-of-the-barrel blame-them-for-everything jobs. Lost lots of people as the economy recovered and the one new person is qualified for a much better job in the company and Is just hanging out untIl that better job is open soon. Also several small restaurants and fast food joints near me in Denver have closed early or for a Day or two cause they can’t find enough workers.

Same here. My department (university IT) is down to 75% strength because of quits, and management is struggling to find anyone to replace them.

I have a friend who runs a retail store, and he says things are similar in his world. Everyone is having trouble finding workers.

While I often appreciate Kevin's "show me the numbers" take as a corrective to hyperventilating media frenzy, this all feels a little glib. Economic statistics are notoriously squirrelly, and you really really need to dig into the details and understand exactly what is being measured.

And Hobijn, incidentally, does NOT say there's "nothing to" the Great Resignation. He just says it's typical of rapid economic recoveries.

Are you saying even the people who work in university IT are unhappy with university IT?

I have a friend who runs a retail store, and he says things are similar in his world. Everyone is having trouble finding workers.

Krugman has joined the skeptics club. As he points out, prime age workforce participation is back to where it was in 2019.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/05/opinion/great-resignation-employment.html

"I have a friend" is the classic intro to anecdote.

While there may be a bit of a point in the first chart, why is no one criticizing the second chart?

One of the entire points of the great resignation (for a better job) is wiped out if you subtract hires from quits. Like, what? Also, what somebody else said: those hires may be some of the lay offs returning to the workforce, and the increased quits are more people leaving it. Some of that washes out, but there would clearly be two stories in there.

Back to the first chart: another commenter posted the FRED non-farm quits/hires chart and it shows quits increasing by about 50% and hires only increasing by about 10%. That's a pretty stark change. The index-to-start-of-pandemic version that shows quits at 125% or so and hires at 111% or so elucidates it further. The narrative arose, and justifiably so, because prior to the pandemic these were pretty much in lockstep - although you might actually be able to see the start of employees calling bullshit on employers leading up to the pandemic, and the pandemic merely interrupted its beginning and accelerated the new trend.

I'm not even a Marxist and that's what I see in the data. I have hope that the political pendulum may finally swing back towards labor just a little bit. The first Amazon union and the coverage surrounding it is another check in that column for me as well.

Thanks for this analysis.

The great resignation was about as real as the death of cities.

Maybe the NYT's will do a thoughtful piece connecting both. Thrown in that trend of teenage girls turning tricks for mall money for good measure.

I am not sure whole economy trends show the real picture. There probably were not a lot of quits in industries that had a lot of layoffs and there were likely more in industries that were doing really well. In the technology industry, I saw more recruiter emails and cold calls than usual and feel like people were moving between companies a bit more than usual. The company I work for is a frequent "top 10 place to work for" so I saw less quits personally. Anecdotally though I am hearing from my friends that work for companies that are forcing a back to office policy, that there is a big talent drain.

It is hard to measure this stuff though because many industries are at the extremes. If you go either from 3% quits to 6% or 200% to 300% it's hard for a casual observer to notice.

The PROBLEM with Hobijn's analysis is the ages he uses and the fact that many of the facets of COVID, and the associated relief bills muddied an already fluid situation

In not particular order

The age group most affected by quits was the older group. They retired IN DROVES to avoid COVID and the associated lack of income. They checked their retirement accounts and saw that they could either collect a reduced Soc Sec amount early OR they could hold off by drawing down their 401Ks or just plain tough it out until full retirement age.

THIS had the affect of "positions" being vacated. When those positions became active again the group that would NORMALLY come BACK to work did not - these jobs were filled by the most qualified candidates the employers could find

Which then lead to:

Less qualified individuals were left with a LOAD of job openings to choose from. (those that could move UP into slightly higher skill set jobs did so)

The boomers are the LEAST educated portion of our work force. Keep in mind that far less of us (as a percentage of the total population of boomers) had college degrees than subsequent groups did. We WANTED college education for our children and their children

But something else is at play here.

Each succeeding group from the boomers

The millenials, The Gen - Xers etc were SMALLER groups because birthrates for those groups had already started declining.

Quite frankly the groups following the boomers were smaller in number but much more highly educated. So when the economy started rebounding you did NOT have the same number of workers but you had the same number of positions and even MORE new positions being created by Biden's economic expansion - coupled with the boomers who were demanding more "services" be provided for them (restaurants, bars and touristy spots). Once COVID declined the increased numbers of boomers wanted to travel and go out to eat only to find restaurants, bars, and hotel staffs severely limited in numbers)

One question remains in my mind though

During the initial phases of COVID there was a program called the payroll protection program that paid employers to keep people who may not have been working on the employers payrolls. How did THAT affect the numbers?

Pingback: The Great Resignation as “Take This Job and Shove It!” - Angry Bear