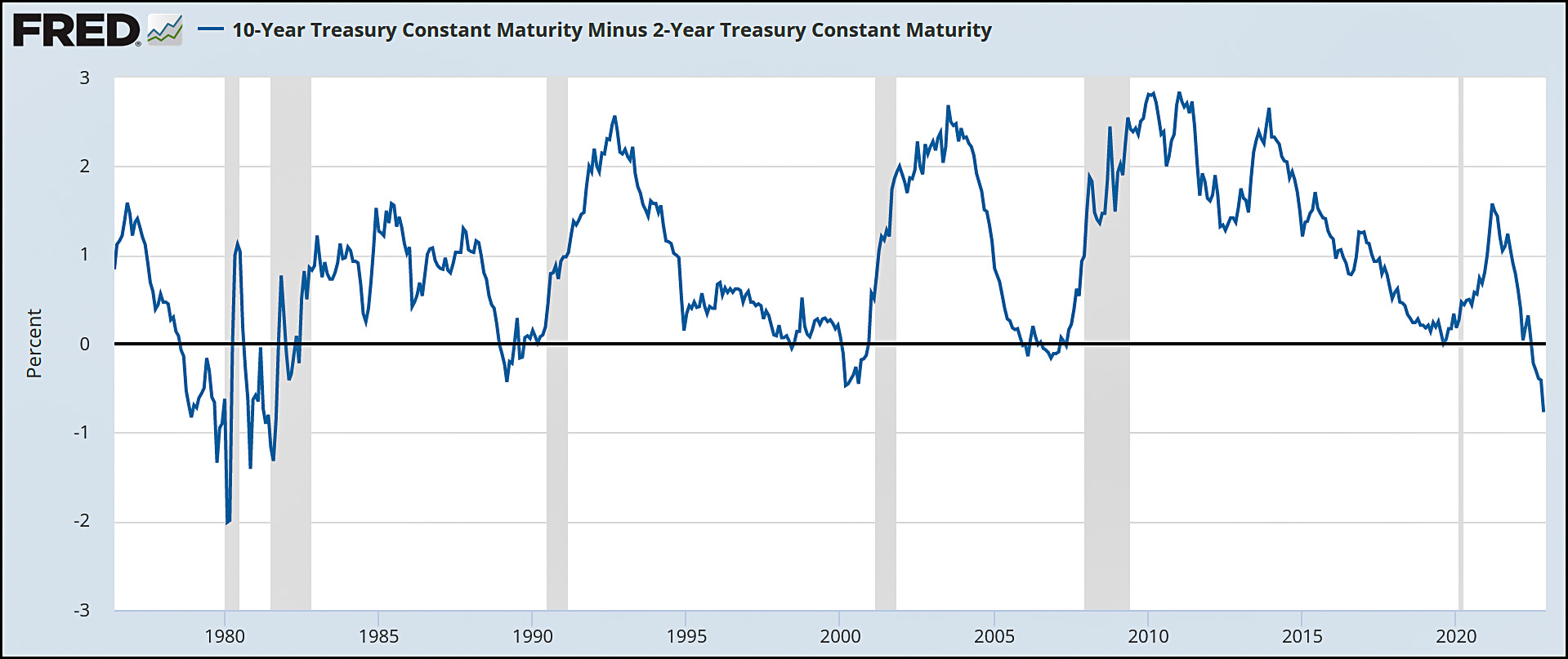

The Wall Street Journal points out today that our ongoing yield curve inversion is getting worse and worse:

Judging from this, we were already due for a natural recession to start sometime in the first half of 2023. Then, a few months ago, the Fed started jacking up interest rates, which will put downward pressure on the economy at about the same time. The Fed could respond to this double disaster by lowering interest rates—which it will—but of course it will be a year too late for that.

Judging from this, we were already due for a natural recession to start sometime in the first half of 2023. Then, a few months ago, the Fed started jacking up interest rates, which will put downward pressure on the economy at about the same time. The Fed could respond to this double disaster by lowering interest rates—which it will—but of course it will be a year too late for that.

We are so fucked. I sure hope I'm wrong about all this.

NOTE: Normally investors demand higher interest rates for longer-term bonds in order to protect themselves against unexpected inflation and Fed rate increases. For example, if the yield on a 10-year bond is 5% and the yield on a 2-year bond is 3%, the yield curve is 5% - 3%, or +2%. This is normal

Sometimes, however, investors are so convinced that near-term prospects are poor—i.e., a recession is coming—that they expect the Fed to fight it by lowering short-term rates. To protect against this they demand super-high rates for short-term bonds. When this happens you get a situation like we have right now: 10-year yields of 3.68%, 2-year yields of 4.42%, and an inverted yield curve of -0.74%.

We will be properly chastened for ever thinking redistributative houghts, however, and hey, having your expectations dashed builds character.

but gas prices will be lower...that's a plus...

I don’t know what makes a recession ‘natural’. Finding the mythical ‘business cycle’ in the drunkard’s walk plotted here is a fool’s errand. We have recessions because economists know as much about how the economy actually works as Theodoric of York knew about disease.

Same. What's "natural" about it? It's always the result of something (or really, a bunch of somethings or somebodies).

What's "natural" about it? It's always the result of something.

Sure, but that "always" is the key word: we always enter recession, in the fullness of time. I mean, maybe in some parallel universe there are economies that never have periods of contracting activity, but in the universe we live in, they eventually, inevitably arrive.

Yeah. Our ancestors no doubt thought outbreaks of smallpox were inevitable.

Right, I understand that, but to say they're "natural" implies that there's nothing to be done about lessening or preventing them, and that there's nothing that ever causes them - they just happen. Not to mention the other socioeconomic ills that come with them (increased redistribution of wealth to wealthier people chief among them).

Same thing with calling car crashes "accidents", just different stakes.

I'd say it's because a) we have a limited toolkit, i.e., no fiscal levers to speak of, and b) no national policy. If you think that's not by design, well, have I got a bridge for you.

The Fed's maneuvering was already well anticipated in January 2022. So I don't see a one-two punch here. Yield curve inversion, Fed moves, they're both aspects of a single phenomenon. Maybe there will be a recession, but it's not a sure thing.

In January 2022, the 3/5/10 year yield was 1.5/1.8/1.9.

In November 2022, the 3/5/10 year yield is 4.2/3.9/3.7.

I'm not sure that the Feds moves were well anticipated back in January. At least not by the people investing in US bonds. What am i missing?

I do agree that it's not a sure thing.

I guess the actual rate of inflation matters a lot more for short-term yields than what anyone expects the Fed to do. Or, to put it another way, thinking that the Fed is going to raise interest rates _if_ inflation doesn't let up is a little different from seeing that inflation is _not_ letting up and knowing that the Fed _will_ raise interest rates.

It's not a sure thing. The underlying strength of the economy seems pretty formidable, tech sector excepted. Mind you, I personally expect we'll be in recession at some point next year, but two recession?

Reading today in Bloomberg that is a kind of misinterpretation. When the yield curve steepens, that’s when things get bad. Here is the article since I know many don’t have Bloomberg. It is long…

By Cameron Crise

(Bloomberg) -- You could probably excuse punters for

trading like we are in something of a holding pattern for the

time being. The next two-and-a-bit weeks will see the release of

key economic data (payrolls and CPI) as well as the final Fed

announcement of the year. There’s little to be gained from

leaning too far over your skis at this point.

Looking ahead into 2023, it sure feels like the fate of the

US economy is perched on a knife edge, though markets aren’t

exactly pricing imminent recession as a foregone conclusion. The

inversion of the yield curve certainly confirms that we’re in a

late-cycle environment, but when will we re-steepen? That likely

depends on just how far the inversion goes.

* It’s little secret that recession talk is heating up. Yield-

curve inversions are generally misunderstood by the financial

chattering classes, who underestimate the time lags between

inversion and an economic contraction. Indeed, as this column

has been at pains to point out over the years, it’s the re-

steepening of the curve that’s the real recession signal, not

the inversion. Still, it’s notable just how much interest in a

possible recession has ticked up, whether you look at a Google

Trends analysis or a running tally of news stories mentioning

the term.

* To be sure, some sectors of the economy are showing clear

vulnerability, and even the labor market is perhaps less healthy

than it appears at first glance given the uptick in continuing

claims. For now, however, financial markets appear remarkably

sanguine about the prospects for the economic cycle -- the

recession probability model discussed a week-and-a-half ago now

suggests just a 5% chance of an economic contraction within the

next year!

* I’d take the “over” there, and I suspect just about everyone

else would, too. That in turn raises the question of how long

the curve can keep inverting, and when it might re-steepen into

positive territory. We’re in kind of an interesting environment,

because market interest rate pricing isn’t “pure” -- it’s

heavily influenced by the Fed’s own forward guidance. This is

the case not only for the near-term trajectory of policy rates

(where the FOMC seems committed to maintaining restrictive

policy for some time), but also the long-term equilibrium (the

2.5% long-run policy rate estimate provides an anchor for yields

further out the curve.)

* While the precise timing of a recession might matter if you

are an economist, those engaged in taking market risk are more

concerned with the performance of financial assets. In other

words, how the curve trades (the ultimate magnitude of the

inversion and when it will end) matters more than when the NBER

ultimately determines a peak in the economic cycle. So what’s

the prognosis? Let’s have a look.

* While many recession models, including the one employed in

this column, use the 3m-10y yield curve as a signal for the

economic cycle, from a trading perspective 2s-10s is generally

far more relevant. The past pattern of behavior of 2s-10s

inversions yields a fairly consistent relationship that makes a

lot of sense when you think about it: the greater the magnitude

of an inversion, the longer that it tends to persist.

* Plugging the current peak inversion (78 bps) into the

regression formula yields an estimated time of inversion of 145

trading days -- about two months beyond the current span. That

would be consistent with a Fed capitulation and legitimate pivot

in the first meeting of 2023. In normal circumstances, that

might be a realistic result in the event of weak payroll figures

this week and next month, as well as further downside surprises

in inflation. Given this year’s Fed rhetoric, however, that

seems awfully premature.

* Of course, there is no guarantee that we have already seen the

peak inversion of the cycle; after all, the curve is only three

bps “steeper” than that threshold at the time of writing. It is

also worth questioning whether there is a purely linear

relationship between the inversion peak and duration, given that

much of the correlation is driven by a couple of outliers. I ran

a similar analysis, but on the natural log of the inversion (the

absolute value of the inversion, to be precise). The r-squared

isn’t quite as high, but the distribution around the regression

line looks a lot more balanced.

* This methodology yields an estimated time of inversion of 197

trading days -- a little more than four months beyond the

current episode. A payroll shocker in early April, anyone?

Obviously, trying to pinpoint the exact date of a disinversion

is a bit of a fool’s exercise, but it is still interesting to

note that if the curve doesn’t keep inverting, history would

suggest that a re-steepening into positive territory isn’t too

far away. The chart of the 2-year is actually pretty consistent

with that notion -- the break of a looming head-and-shoulders

neckline would target yields around 3.84%.

* OK, that is still above the current level of the 10-year

yield, so it wouldn’t necessarily result in a disinversion.

Still, that sort of move would certainly get more tongues

wagging! Another way to approach this problem is to assume that

Fed guidance is rock solid and the curve doesn’t disinvert until

a year from now. What’s the peak level of inversion implied by

such a long duration of an inverted curve?

* Using the formula from the log chart above, we can back out an

answer: 120 bps. That actually seems kind of reasonable if and

as the Fed keeps ratcheting rates up. Would it really surprise

you to see the 2-year at 4.80% and the 10-year at 3.60% over the

next couple of months? Me neither.

* Obviously, we are in an environment of enhanced uncertainty on

the economy, and increasingly about the trajectory of monetary

policy. As inflation keeps decelerating and the labor market

weakens, policy expectations are going to exhibit a lot more

two-way volatility than has been the case for most of this year

-- at some point, the Fed will turn more dovish (or less

hawkish.) A base case of further curve inversion that is

reversed by the spring actually seems pretty reasonable. Let’s

see if the data and the Fed play along.

* NOTE: Cameron Crise is a macro strategist who writes for

Bloomberg. The observations he makes are his own and not

intended as investment advice. For more markets commentary, see

the Markets Live blog.

Many thanks for the effort you went to in posting this article!

A further note, heavily anticipated recessions tend to be shallow and mild - it is surprise crises (as in 2008) and particularly banking / financial crises that tend to be particularly deep and destructive.

Thanks for the read of the entrails. But the pressing question remains, how many economists do we need to toss into Mauna Loa to avoid a crash? I kid!

Cheap Money Yesterday!

Cheap Money Today!

Cheap Money Tomorrow!

Or so seems Kevin’s desire.

Generally - although it is largely clearly politics-driven motivated reasoning rather than a truly rational opting for cheap money (as the hand-wringing over interest rates returning simply to pre-2008 financial crisis normal is not rationally a catastrophic issue).

For Lefties they can rather more profitably read Krugman for proper and well-grounded reflexion.

Lowering the cost of investment while increasing employment and wage gains for the working class is not such a bad desire.

Why would expensive money be a good thing?

ahhh.....

When cheap money goes towards consolidations and "rent seeking" to build monopolies and monopsony, then it is "bad". Of course, that is also a function of the regulatory environment and tax set up.

That said, the Fed's have pushed rates way too high, relatively speaking.

Why would expensive money be a good thing?

Why would ever-cheapening money be a good thing? Most people don't have the means to automatically acquire more dollars to cancel out the effects of the dollar's loss of value. And so their living standards take a hit. Sometimes (especially for the non-wealthy) painfully so.

It's high time to do unto the aristos what they did unto the kings of yesteryear. We don't have nice things not because of happenstance or coincidence, but because of enemy action.

You seem to be calling for off with their heads.

Liquidate the Kulaks, etc.

I'm thinking of something more along the lines of Runnymede. My ancestors hailed from the Hanseatic League, so I come by it honest.

One recession may be "barrelling" not two.

and that is how inflation - supply-demand imbalance - is cooled.

A modest recession that bleeds out inflation and then has a rebound is a better result for the Democrats than ongoing financially-comfortable-educated urban Democrats inflation denialism

Neither is good, but given the choice between inflation and recession, the proper choice is always inflation; its a more equitable sharing of the burden.

There are lots of people out there who don’t care about anything bad happening unless and until it happens to them. We generally call them MAGA Republicans, which have eaten most of the non MAGA Republicans and quite a few ostensible Democrats. (The “I voted for Obama then Trump” crowd.) Lounsbury is among them.

Doesn’t matter how many people need to starve or die or be ruined forever, as long as the Lounsbury’s of the world don’t have to pay a dime more for gas, chicken, whatever ever again. And there are tens of millions of Lounsbury’s in America, which is why we’ll go down the path of making future home purchases more expensive in order to somehow lower food and gas prices today.

Oh, he's not even that. Lounsbury's lack of a formal education has given him a massive inferiority complex, which is why he presents as a troll, subtype butthead-oppositional.

Oh, for sure, demand for gas, and its price, will come down when we fix it so a couple million workers no longer have jobs to which to drive.

given the choice between inflation and recession, the proper choice is always inflation...

Your "always" is doing heavy lifting. It depends on the level of inflation and (alternately) the intensity of the recession. It also depends in part on the structure of the safety net (if any) a given country operates. Mild, temporary inflation is better than a harsh recession for most Americans, agreed. A long slog of double-digit price increases is bad, though, and moreover makes the eventual recession harsher still. Unlike Kevin, I think there's a fair chance we'll all be thanking Jerome Powell two years from now, because the Fed's reasonably decisive action (I wish they had acted sooner, mind you) might well mean the downturn is shallow, and doesn't last too long.

Kevin, this is getting embarrassing for you.

First of all, the 2/10 curve didn't invert until July. We weren't "already due for a natural recession to start sometime in the first half of 2023" before the Fed started raising rates. The rate rises started in March and got serious in May.

But more importantly, the yield curve inverted because of the rate hikes! This isn't a 1-2 punch. It's all the same thing! The rate hikes caused the yield curve inversion. Overnight interbank lending (the "rates" that the Fed hikes) are quite high and anticipated to get higher, so short term Treasury yields are up. But long term they are unlikely to stay this high, so long term Treasury yields are not up as much. This is what caused the yield curve inversion.

We might be headed towards a recession, but it is not a 1-2 punch double recession - it's just the one "the Fed raised rates too high and didn't reverse course quickly enough to avoid a mild recession" recession.

By the way - what is your definition of "so fucked"? What does "so fucked" look like? Unemployment rate at 8%? 6%? 5%? Because we might get a "recession" without seeing the unemployment rate ever get that high. Is that "so fucked?" I guess it depends on your definition.

Thanks for putting words to this. It does seem to be this exactly:

"Overnight interbank lending (the "rates" that the Fed hikes) are quite high and anticipated to get higher, so short term Treasury yields are up. But long term they are unlikely to stay this high, so long term Treasury yields are not up as much."

I'm not even sure they're expected to go higher anymore. And I think everybody expects that the Fed will have to back off slightly on what the rate is, which I think is what is reflected in the 10Y yields.

"We are so fucked" is definitely a change from the "That thing you're worried about? It doesn't really matter." attitude that has become pretty standard on this blog.

To be fair, I believe that Kevin is talking dominoes; as the economy goes, so goes the 2024 elections. And I find I cannot gainsay that opinion.

My cousin could truly receive money in their spare time on their laptop. their best friend had been doing this 4 only about 12 months and by now cleared the debt. in their mini mansion and bought a great Car.

That is what we do.. https://earningblue.blogspot.com/

The inverted curve is just another factor on how the Fed has overreacted. For those who argue for “expensive” capital vs “cheap money” the real question is what helps society more-what approach leads to greatest GDP growth and what benefits the greatest amount of people. The evidence suggests that “cheap money” is preferable. Higher interest rates are simply a manner for restrained growth which obviously is what the Fed is trying to accomplish: the theory being that the lesser the flow of capital the lesser the inflation but that is not always the case unless one wants to simply slow down economic activity (excessively relative high rates would freeze most lending) and people would eventually stop spending which presumably would lead to less inflation, but to state the obvious: rates can be increased in such a way that they create more harm than good-there is no inflation when people don’t buy or sell goods or services but there is also no economy.

And apropos of nothing here's Krugman on the relative hardships of inflation, who it helps and who it doesn't. His argument, as he readily admits, has an asterisk on the asterisk.

http://www.richsalaries55.blogspot.com/

My cousin could genuinely get cash in their extra time on their PC. their dearest companion had been doing this 4 somewhere around a year and at this point cleared the obligation. in their smaller than usual house and purchased an extraordinary Vehicle.

That is our specialty. http://www.richsalaries55.blogspot.com/

Lags have been addressed already - a distributed lag would be the best phrase to describe the response with the effect of policy spread over time. And why begin in May rather than March?

More importantly, the Fed was fighting inflation back in late 2021 when they started to aggressively unwind Quantitative Easing (QE) and reduce the monetary base (MB). Looking at how MB changes would be a much more useful approach than looking at interest rate changes.