Take a look at this photo:

- This is a small white house.

- This is a white small house.

The answer is #1, of course. The second description sounds obviously wrong even though it just changes the order of the adjectives. Native English speakers understand this intuitively even if nobody ever taught it to them. I certainly don't remember this ever being a topic in any of my English classes.

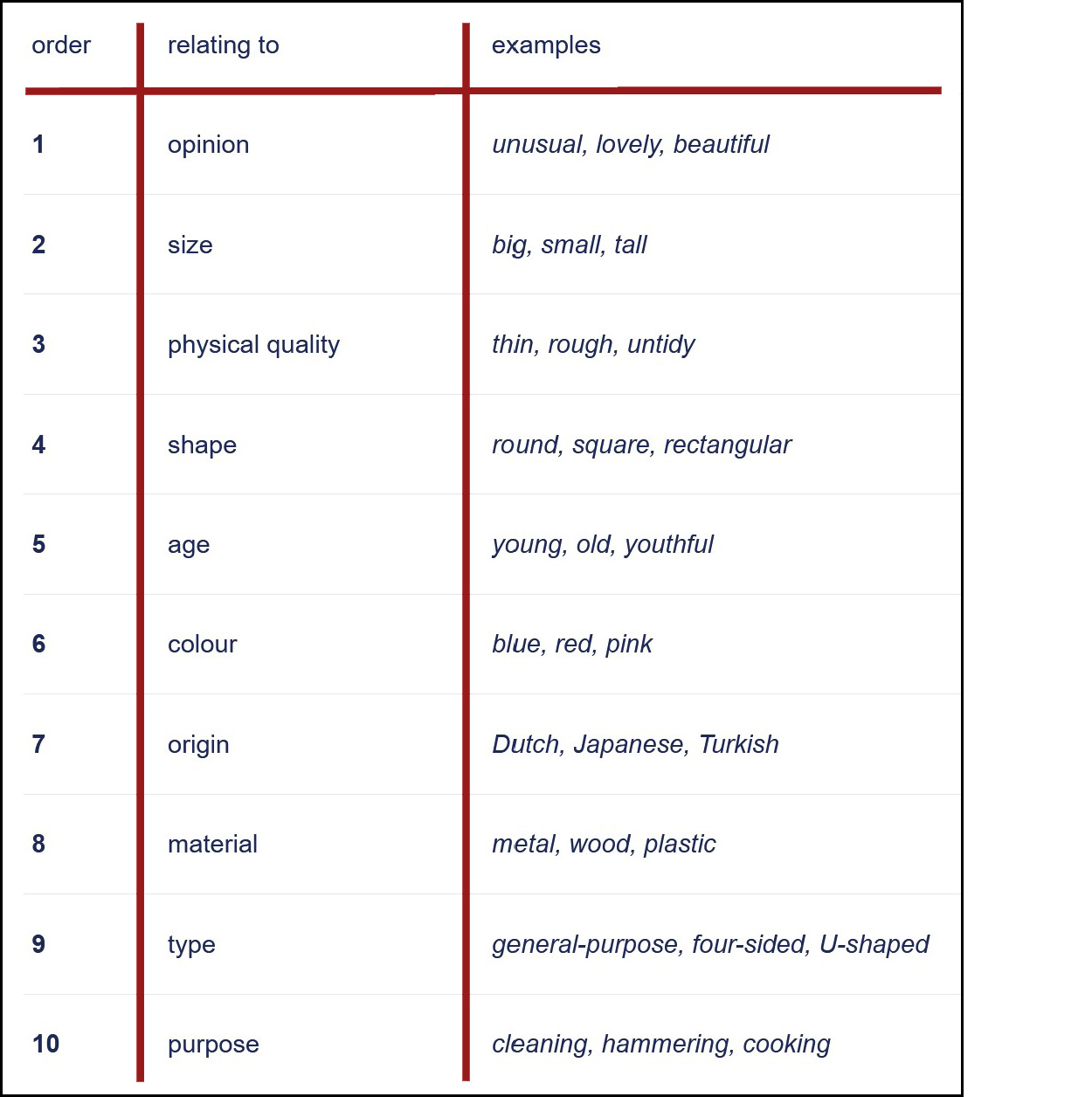

But is this an actual rule? It turns out the answer is yes. The Cambridge Dictionary provides this handy table:

Some of you know this already, but I only found out about it a year ago. I happened to be reading a piece about teaching ESL and it turns out this adjective order stuff is a huge pain for English learners. Now you know.

Some of you know this already, but I only found out about it a year ago. I happened to be reading a piece about teaching ESL and it turns out this adjective order stuff is a huge pain for English learners. Now you know.

so.....

A red brick house.

is really supposed to be

A brick red house.

???

Well no. Color comes before material.

Did I mention, it was a house with vinyl siding the color being "brick red"?

😉

In that case it should have been "brick-red house" (a house that's the color of red bricks), which is not the same as a "brick red house" (a red house made of bricks").

"Brick-red house" uses the hyphen to signify that "brick" is modifying "red," not "house." That obviates the ambiguity you point out.

The color red is describing the brick, not the house.

That's another one that confuses ESL speakers. We put a string of modifiers in front of a noun, some of which modify the noun and are therefore adjectives, and some of which modify adjectives and so are adverbs, and it's not always obvious which is which. Just to make it even more confusing, the modifiers are often nouns in their own right in other contexts. For instance, is a "small dog house" a house for a small dog or is it a small house for a dog? In that phrase "dog" which is commonly used as a noun, is an adjective and "small" which is usually an adjective, may be an adverb.

If the brick-red house were that color, but not made of bricks, I'd use a hyphen for the compound adjective.

Speaking of which, build vs. made?

I sometimes tutor ESL for students and that is a brutal challenge for non-natives. It is an EASY way to tell if someone is a native speaker or not. The order confuses non-natives.

I see no reason to make it a lesson for English learners unless they plan to work in handling public communications with native English speakers.

Over time they might pick it up, but it seems like a matter of stylistic nuance.

i don't imagine it would be a lesson except for a very advanced class, but i can see it as something that would come up in the course of teaching and you'd want to be able to explain it when asked.

It's true. If this is the only think you are getting wrong then you are already an excellent English speaker.

I taught ESL for a while, many years ago. I sometimes think about how I would approach this now. Were I to do it now, and if I had the freedom to set up my own curriculum, I'd focus mostly on vocabulary and phrases and very little on rules. Someone who knows lots of words and phrases but uses incorrect grammar is still easy to understand. Someone who can conjugate all the verbs but has few words at hand can't even ask where the bathroom is.

Native English speakers don't understand such word order "intuitively", that is instinctively, although according to Noam Chomsky a lot of language is instinctive. Word order may be completely different in other languages - for example in romance languages adjectives usually follow the noun. What kids of the right age do is memorize words and the somewhat arbitrary word order of a language at a very high rate. If they hear "small white house" once or twice they have this phrase in memory - they don't have to learn the rules according to the Cambridge Dictionary (and nobody teaches those rules). This ability usually drops off with age. I would bet that the non-English speakers who have difficulty with the order of adjectives are the older people who have passed the age of rapid language learning.

I think it's mostly the opposite. Native English speakers do not only memorize specific strings of adjectives—they learn the rules of adjective order implicitly and then intuitively apply them without consciously thinking what they're doing. The proof is that you can give multiple native English speakers new strings of adjectives they've never heard before and they'll all put them in the right places with far higher than random chance (and far higher than non-Native English speakers). For instance, how should these words go together?

small Turkish donkey red cooking unusual

English has no real rules.

I would say " A small house, that is white."

This is utter nonsense. Of course English has real rules. This is why "John hit Bob." and "Bob hit John." mean different things. That being said, there are a lot of fake rules people make up for various reasons and get very huffy about. The hallmark is that native speakers learn the real rules without their being explicitly taught. Listen to a toddler speaking and you will hear various grammatical errors. Come back a few years later and they are gone. Feel free to correct the toddler if you want, but it won't make a damn bit of difference. The kid will learn English grammar at the same pace regardless. The bogus rules are the ones that you have to learn explicitly. The tipoff is that there is an industry selling grammar advice to native speakers. This advice is pretty much entirely bogus. People won't pay to learn the real stuff, because they already know it.

Now that we are talking about "learning" grammar "rules," the one that so many have learned but that is entirely incorrect, is that when you refer to yourself in some kind of serial clause you always say "I" and never "me".

As in: John and I are going to the store.

But also: Grandma gave a Christmas present to John and I.

It is absolutely unbelievable how many people don't know that one of these is incorrect.

Now as to why so many kids intuitively don't want to use the subject form of "I" when connecting via a conjunction even when it's part of the subject of the sentence, I don't know. But that at least is an honest mistake and has a certain colloquial charm. Using the subject pronoun where the object pronoun is needed . . . that requires a bad education and makes you sound like a stuffy, over-precise prig, like refusing to split infinitives or end a sentence in a pronoun. And it's wrong!

I think I know what makes people tend to say "John and me" all the time, or "John and I" all the time, and in this case the taught grammar rule is just not natural. I learned it and understand it, but I often get it wrong when I'm speaking without thinking.

I have asked myself why I get it wrong, and my feeling is that my language center looks to the words most closely connected with "I/me" and chooses the word that fits that near context, which takes precedence over the farther-away context. So in "John and (I/me)", my brain wants to settle on one choice of "I" or "me" to fit the "somebody and somebody" form. Even though the taught grammar rule doesn't work that way.

Not really. Being intelligible is not a rule it's a consequence of language. You might as well say it's a rule that you need to eat. But unlike other languages like French there is no language rule making body in English.

I'm afraid you're still wrong. Every language has rules, and English is no different. The rules exist even if they are unspoken. That there is no Académie Anglaise is irrelevant.

Language represents a shared rough consensus among a group of speakers (or, perhaps, a collection of shibboleths). Even without official rules, you can imagine a virtual machine consisting of the rough consensus within the group that a given statement is "correct." If we were to treat American English as a single consensus-group (which we shouldn't - see below), its "correctness machine" would accept the statement "the small white house" as valid, and suggest that "the white small house" is wrong in some way. The two sentences are equally intelligible (barring edge cases arising from conversational context), but one clearly sounds "right" and the other clearly sounds "wrong" to native speakers. This means there is a rule, even if no official body ever tried to impose it. The chart Kevin posted is based on attempts by linguists to describe the unspoken rules governing adjective order in English, based on observation and by asking native speakers to rate statements as sounding like "good" or "incorrect" English.

To further muddy the issue, though, these rough consensus rules can and do change over time. In English, "data" is now often considered a mass noun (taking a singular verb), even if older scientists kick and scream at this heresy (which their students ignore and continue saying "the data is..."). "Cool" and "hot" can now be antonyms or synonyms depending on context, which exercised older folks to no end in the 20th century. The new rules are still rules, though - watch any teenager cringing at their parents using slang the wrong way. Slang may exist in an informal register, but it nevertheless obeys its own rules.

And to return to a point in the second paragraph, these rough consensus rules are not consistent across a population. Native English speakers in Pittsburgh will confuse native English speakers from Los Angeles by referring to them as "yinz," while native English speakers from Atlanta might prefer "y'all" as the second-person plural pronoun. And all this is to say nothing of the incredible divergence in what is considered normal speech among specialist groups - a bunch of (American) football enthusiasts and a bunch of neuroscientists will have very different expectations of what you mean by the word "spike" (and may even expect it to be a different part of speech). A given individual will often be part of more than one such consensus group, and will fluidly exchange one "flavor" of speech for another (a process known as "code switching") based on context - and they may even be unaware that they are doing so.

As an aside, even a language's "official" rules often don't describe reality very well. Let's look at your example of French. The Académie Française sets nominal rules for French, but these rules have less effect on actual spoken French than you seem to believe (or than the Académie itself would prefer). For a well-trodden example, take the word for "computer:" the Académie insists it is "un ordinateur" (following IBM's marketing department coinage), but in French spoken by native speakers in France it isn't at all uncommon to hear "un computer." This is by no means the only example.

All this is to say: every language has rules. Some languages have "governing" bodies that fool themselves into thinking they are able to dictate usage. The actual rules are unspoken, are (mostly) subconsciously understood by speakers, change over time, and change dramatically with social context. But they are still rules.

This would almost be a decent argument if there were only one way to be intelligible, used across all languages. But of course this is not even close to true. English uses word order to show who is doing the hitting and who is being hit. Latin uses case markers. These are rules of grammar. I suspect that you are so used to hearing "rules" used for bogus stuff like not ending a sentence with a preposition that you have internalized the notion that rules of grammar are bogus.

We do have rules. One we are taught early in school is that one's voice goes up at the end of a question.

It turns out that ISN'T the rule.

The rule is one's voice goes up at the end of a questionif the speaker is expecting a yes or no response. The voice goes down if the speaker is expecting an informational response.

That's why this conversation:

Q: Is your car blue or red?

A: Yes

will result in the urge to pucnh the responder IF THE VOICE WENT DOWN, and not IF THE VOICE WENT UP. Try it yourself.

It actually looks like a duplex (i.e., two houses).

Native speakers don't understand the rule "intuitively," of course. They learn it without consciously knowing that they've learned it.

What's really hard to keep track of is how location prepositions (e.g., in, on, at, etc.) vary from one language to another, even with closely related languages.

Location prepositions are often arbitrary. For instance, I learned "by accident". When I see or hear "on accident" it grates, even though it's become common usage. By the same token some people wait "on line" and some wait "in line". To me "on line" means, approximately, "connected to the internet". Waiting on line is what you do while waiting for a web site or app to load.

Waiting on line was an expression used by all my relatives in northern New Jersey and NYC area. No other area seems to use that construct. It predates the internet age.

Prepositions are crazy.

"Native speakers don't understand the rule "intuitively," of course."

While I agree about the main sentence, the "of cource" is not that obvious. Chomsky and friends, for example, will claim this kind of things are built in the LAD (Language Acquisition Device).

Sure, but it's still learned, not intuitive.

After you've learned, it becomes intuitive.

It's not like the early graphical user interfaces for computer operating systems which the companies said were "intuitive" when they clearly were not, at least not until people learned them.

This will come in handy to describe my lovely, small, thin, round, old, red, Japanese, wood, general-purpose cleaning utensil.

I remember when I had a Japanese old general-purpose wood thin lovely round cleaning red small utensil. But you probably couldn't relate.

If you want real fun with stuff you know without knowing you know it, look up phrasal verbs. These also give ESL students fits.

Yes! German has load of those, too.

Clever way to feature another one of your neat photographs!

The hardest thing I found when helping non-native speakers is the many uses of prepositions that are inherently meaningless and must be learned by brute memorization:

I’m into that.

I’m over that (because it’s behind me).

I’m all over that.

I’m above that (because it’s beneath me).

I’m onto that.

I’m behind that.

Truly maddening.

So true! And things like the difference between "I don't know anything about that" and "I don't know about that".

...Or the difference between "few good men" and "a few good men," Which trips up deaf people because they generally don't use the little words at all in their language.

Just as tough are just general colloquialisms that native speakers take so much for granted we don't even think about them. I once had a Chinese ESL student who was very bright and actually spoke excellent English but wanted to learn to speak more like a native speaker. As an exercise I gave her a short Newsweek article (this was the early 90s) to read and she basically couldn't make heads or tails of it because it was chock full of phrases like "make heads or tails". At the time it really took me by surprise. I remember having a conversation with her about what it means to say to someone "Let's play it by ear."

Indeed. I'm down with that!

If you're over it, then it isn't behind you, it's under you. But I'm past all that.

I have actually seen this ordered list before, and at least to some degree I guess most of it comes natural even to me even though I'm not a native English speaker. But it raises a question:

In Swedish we don't have rules quite like this, although some ordering may come more natural than others. You can pretty much choose to say either "the small yellow house" or "the yellow small house", but the meaning can be interpreted slightly differently. The first alternative is probably the most common, if the two characteristics 'small' and 'yellow' are of the same importance (or if 'small' is more significant than 'yellow'), but the second alternative gives a slight emphasis on 'yellow', for example if there are several small houses to choose from and you want to point out the yellow one you would probably choose this alternative.

So my question is this: If you want to achieve the latter interpretation, i.e. talk about the yellow one among several small houses (but you still have to include 'small' because there are other, larger houses around as well), can it at all be done by breaking the order of adjectives or would that just sound wrong? I.e. is the rule so strict that you have to work around it (like for example emphasizing 'yellow' as you speak)?

Such more or less unknown but oh so important rules in various languages are so intriguing!

I think English could work basically the same way in a similar context. Generally you'd say "little yellow house" but context might change that in some cases, especially in conversation.

In English, you would only say, "the yellow small house," in order to draw attention to its yellowness being a distinguishing factor, to separate it from other small houses that are already part of the conversation.

This is incorrect. "the small yellow house" and "the yellow small house" would both be entirely usable English and the preference would depend on context.

Discussing a number of yellow houses situated among a bunch of blue houses, where the yellow houses vary in size: small yellow house

Discussing a number of small houses situated among a bunch of large houses, and one of the small houses is yellow: yellow small house

So although the ordering is "a rule" it can be bent for contextual reasons, where the context consists in part of the *most* distinguishing factor(s).

That's exactly what I said.

Ah, so you did. Mea culpa, apologies.

Totally agree with y'all's point, but I think it's notable that while these order rules can certainly be bent, native speakers follow them the vast majority of the time. It's pretty rare that you want to emphasize the yellowness of the small, yellow house.

As a super quick check, a search in Google for the string "yellow small house" in books turns up 11 results, a few of which seem to be junk results that don't actually include the phrase. Meanwhile the same search for "small yellow house" has 450 results. (Searching in books bc they are full of real fluent language, while the web includes a lot of search-engine optimization, weird computer-format phrases, etc.)

Furthermore, my guess is that if a native would say "the yellow little house" people would realize that the order is changed to emphasize the color aspect, while the result might be a bit different if I say the same thing. Since I have an accent that reveals my non-nativeness, a listener may very well deduce that I simply don't grasp the rule regarding the order of adjectives, not realizing my intent. So, probably better to stick to the correct order and instead emphasize 'yellow' if needed.

On the other hand, the question is probably mostly academic. Context and whatever else you say will for sure make clear what you mean.

Hah! I've always wondered about this. A certain order of adjectives just sounds right. Nice to know there's a rule.

But is common usage based on the rule or is it the other way around?

Not being a native English speaker I obviously don't really know about English specifically, but I would guess all rules regarding language comes from how the language is used first and foremost. The rules change over time, after all, which they would not do otherwise. Meaning that we learn a set of rules at school, which we follow more or less strictly during our lifetime. Then, by the time we reach, say, 50 years of age, we get annoyed by the young breaking the rules we learned and mutter about the good old days when people spoke/wrote properly. And then we find, to our dismay, that the rules have actually been changed (although somewhat lagging), because those responsible for the rules closely monitor how the language is used, and take (hopefully) wise decisions about what changes are inevitable and natural in the evolving language. Which is why "language policing" in general is risky business.

The rules are based on common usage. The rules of English grammar, and spelling, and punctuation, etc. are descriptive rather than prescriptive.

The first is by Douglas Hofstadter. I think the second one is as well, but I'm not sure.

"Verbing weirds language." -- "Calvin" (Bill Watterson)

We'll get off at Denver.

We'll get off in Denver.

Is Denver a point, or not?

That depends on whether the Denver in question is a small village in Norfolk, England, in which case you would get off in Denver; or a mid-size city in Colorado, USA, in which case you would get off at Denver.

I have no evidence to support this, but I'd say "at" denver if I were on the train, and "in" if on a plane. The former is one stop on a linear path with limited options at which too disembark at one of the stations along the way. Planes are less constrained in routes. At the risk of triggering a discussion on the other preposition, I suppose one could get out of a car in Denver, but I would not get out of a car at Denver.... unless perhaps I had hitched a ride an they were going on to Grand Junction and I wanted to go to Cheyenne.

Grew up in the UK. My recollection is that in Br. English, "at" is reserved for points, and "in" was for everything else. So you would get out at the 5 way intersection with the war memorial in the middle. But you would get out in Darlington.

Moved to the US 3 decades ago. Had to get used to "at" being used for both points and non-point locations.

As I understand French, they specify that "at a restaurant" means at the door, but not inside. They reserve "dans" for inside.

Strangely you might also say "I am there" when you have made a trip and arrived at the destination. In English we might say "I'm here" or "I've arrived", but never "there".

It's quite maddening really.

If I were on the phone with a friend who was no where near the place I'm at, and he mentioned that place, I would definitely say something like "I'm there right now". Though if O;m arriving to meet my friend somewhere I'd text "I'm here!"

So it depends on the location of the person I'm communicating with.

I remember in freshman English, being marked down for failing to use a comma between two adjectives describing the same noun. A quick trip to the googles gives links saying that this is true for coordinate [roughly equal] adjectives, describing the same noun, but not cumulative adjectives. One suggestion to test is (to the point of this post) whether the sense changes if the positions of the adjectives are swapped.

Notwithstanding the chart presented, I'd have put a comma between them.

Cheers!

A long time ago, I heard William Safire talking about just the subject: a native speaker's knowledge that, for example, certain adjectives go in a certain order. I forgot the name of that type of knowledge and I've been trying to find it ever since.

"Black and white" is the English order. However, French, Spanish and Italian see things in white and black.

It's an quirky language feature with a quirky name: "the royal order of adjectives."

https://www.hip-books.com/teachers/writing-about-reading/adjectives/

I've been studying French and there is a similar question of when and where to put the French adjectives. An assist for FSL learners is an acronym "BAGS" (and there are a couple of others very similar). It says Beauty, Age, Goodness, and Size are to be placed in front of a noun, but others go after.

They also have some adjectives which can be placed before or after the noun with different meanings.

A thing about this I found intriguing is that some French natives who assist learners have said THEY never learned this acronym (or some other important things about their language) in schools. Some had NEVER heard of it.

Yes, English is nasty and French is difficult, but we change them only incrementally and slowly because a lot of people have to be on the same page about what the language is. If you change them too quickly, perhaps to "fix" them, it confuses a lot of people and does a lot of harm.

Still, the French "de" is absurdly over-used.

Context is important.

"The white small house has a porch; none of the others do."

Pingback: Adjective order in standard English | Later On