We've done it. We've now measured everything worth measuring, so we're moving on:

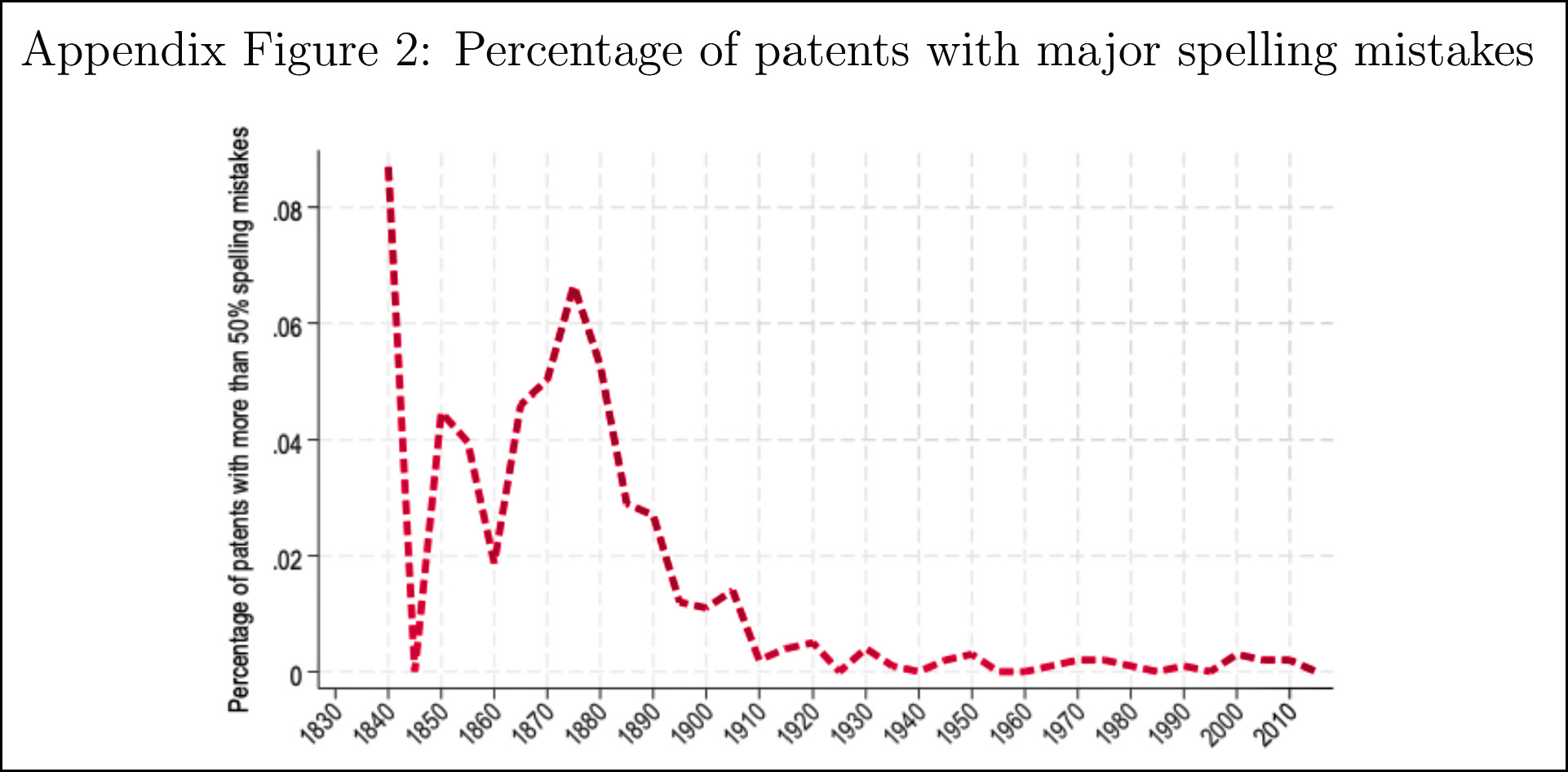

This comes from a paper about patents. The author believes he can identify "creative" patents by analyzing word pairs: if a word pair has never been used before, it's a sign that a patent is breaking new ground. However, old patents are digitized using OCR, which can produce lots of misspellings. This screws up the search for new and exciting word pairs.

This comes from a paper about patents. The author believes he can identify "creative" patents by analyzing word pairs: if a word pair has never been used before, it's a sign that a patent is breaking new ground. However, old patents are digitized using OCR, which can produce lots of misspellings. This screws up the search for new and exciting word pairs.

So the author searched for misspellings in the entire corpus of US patents. After 1910 they become rare, so he limited his study to patents after that year. The chart above is perhaps TMI, but he included it in the appendix of the paper just to show that he'd done the work.

I have a hard time according this "research" the credibility the author might expect, for one big reason--the labeling of the Y-axis.

(1) What the heck is "more than 50% spelling mistakes?"

(2) Is the two-decimal number on the Y-axis the "percentage of patents" or is it the fraction of the patents? In other words, does .02 mean two percent or does it mean 2/100 of one percent?

A half-assed presentation of data renders the data useless. The author needs to take a lesson from Kevin. We may disagree with Kevin's data, or we may disagree with the conclusions he draws from it, but we seldom fail to understand it.

Or you could look at the paper, find the chart, and read the caption which explains the figure.

Or you could look at the paper again, look at my comment again, and read the words carefully, which explain why

(1) The labeling does not agree with the data, and

(2) The question regarding the use of the phrase "percentage of patents" remains unanswered.

Sloppy work diminishes credibility.

Mor thn 50% speling mistakes? Howe is tlht even posible?

They can't close up shop yet. I've never seen an empirically-derived answer to the question, how many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie-roll?

You should have looked it up. Purdue says 364

https://library.bc.edu/answerwall/2018/02/26/how-many-licks-does-it-take-to-get-to-the-center-of-a-tootsie-pop-mr-owl/

1910. The year of peak spell-check.

Or we could just accept that the premise of this paper is obvious nonsense and move on.

As a researcher with a number of patents under my belt, I hate the darned things. They usually go something like this:

Decades ago, Food Company patents Tomato Casseroles. There was nothing particularly novel about this, even back then, but USPTO is kinda clueless, so it is what it is. FC got its tomatoes from Tomato Company (TC), and FC claimed in its patent *any* type of tomato, but specifically called out Type A, B, C, D, E and F tomoatoes as being specifically useful for casseroles.

Then, just before the patent expires, TC patents a new tomato Type G, claiming its use in casseroles. All they really have to do is show that G is better than another reference tomato of TC's choice by a single metric of TC's choice. For example, they could show G has a better shelf life than B, and the fact that B has a crappy shelf-life which would be easy to exceed is rather irrelevant. So would be the fact that G tastes like cardboard or has poor yield or whatever. USPTO sees some lame data saying G beats B at something, and that is enough for a patent.

So why would TC patent a tasteless, low-yielding tomato with mediocre shelf life? Because USPTO is stupid. The game TC will play is to define "Type G" ridiculously broadly and ridiculously convolutedly, so that USPTO's underpaid examiners don't realize that the definition of "G" also includes some or all of A, B, C, D, E and F, which are already commonly used, or includes theoretically superior types H, I, and J which TC has not actually found a way to make yet. Once granted, this bull-manure could theoretically be challenged in court, but it is almost always easier for competitors to settle or waste money on workarounds.

Honestly, if I was in charge of this system and not allowed to scrap it, I would set up a six month public review period where competitors were allowed to submit prior art references and related analysis and explanation to the examiner. THEY have the expertise and motivation to rip these things to shreds.