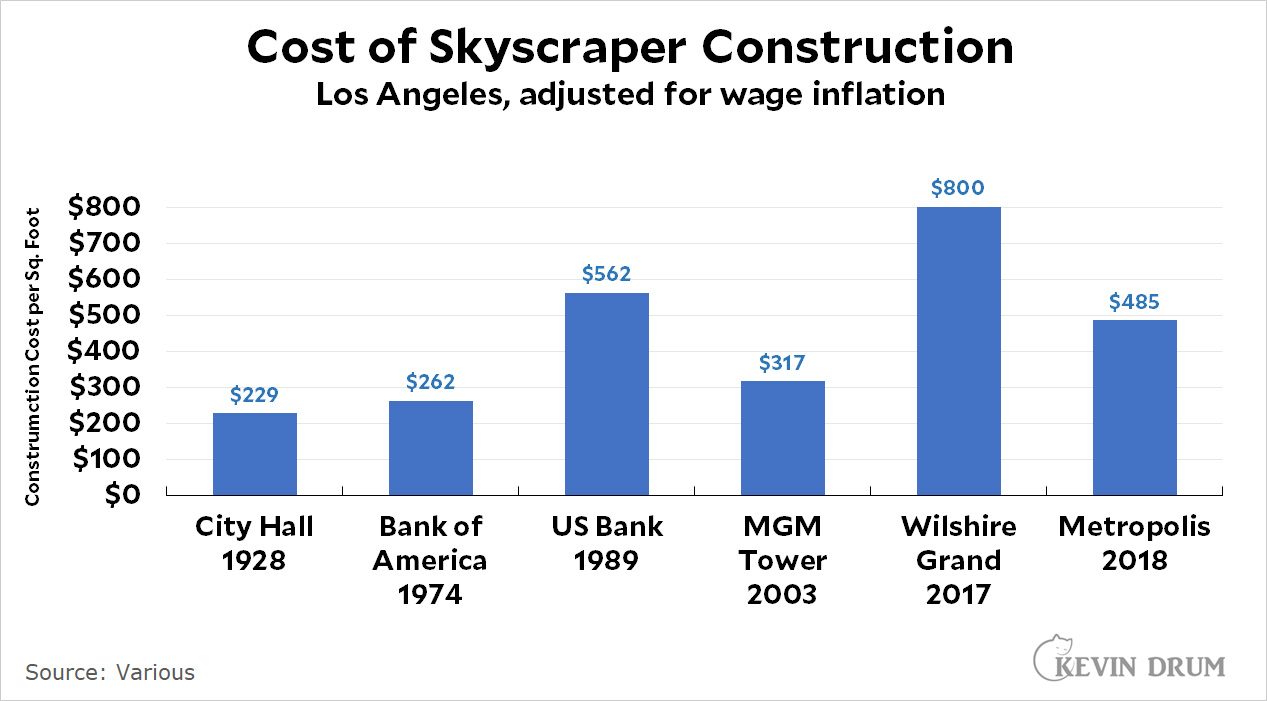

Why is it that we've seen no productivity gains in the construction field? For example, here's the cost per square foot of building a skyscraper in Los Angeles over the past century:¹

Construction costs vary depending on both the type of building and what's being counted. The cost of the Wilshire Grand, for example, includes the entire plaza. The tower alone cost less, but nobody ever seems to break down costs so you can do an apples-to-apples comparison.

Construction costs vary depending on both the type of building and what's being counted. The cost of the Wilshire Grand, for example, includes the entire plaza. The tower alone cost less, but nobody ever seems to break down costs so you can do an apples-to-apples comparison.

That said, there's clearly an upward trend, and it's probably safe to say that it costs more to build a building in LA than it did a century ago. Why? Shouldn't we expect that productivity gains over that period would make it cheaper to build?

Several people have lately taken a crack at this question, but is it really a mystery? Productivity gains come from automation, and the construction industry has barely automated anything in the past century. To build a house, you mark out a foundation, dump in some concrete, erect a frame, and then fill it up with stuff. All of this is done by people using hammers and wrenches and nailguns, the same as it's always been done.

Commercial construction is bigger, but not much different. You need cranes and elevators and miles of plumbing and electrical work. Pretty much all of it is done by hand, and there's no reason to think that manual labor like that should become more productive over time.

Beyond that, modern buildings are earthquake proof, flood proof, fire proof, and more efficient—all of which add to the cost of construction.

Is this ever going to change? "Automation in construction" is a thing, but even today it's still talked about in terms of what it "might" accomplish if anyone adopts it. For now, there's very little on the horizon and construction is just another victim of Baumol's disease.

¹Why Los Angeles? Because New York City is a world unto itself and isn't remotely representative of the US as a whole. LA was the next biggest city, so I chose it instead.

And in case you're wondering, the reason I didn't include any skyscrapers between City Hall and the Bank of America building is because there aren't any. Skyscrapers taller than City Hall weren't allowed until the early 60s, so the entire era from 1928 to about 1965 is a wasteland, skyscraper wise.

You’ve adjusted for wage inflation. But not inflation overall. Are wages indeed the dominant component in skyscraper construction?

About 40%, usually.

Materials then being the other 60% I assume.

Yep.

There is simply a lot more stuff inside of a building’s construction assemblies. More wires, more insulation, more sensors, more equipment, more layers in the wall assembly, &c. Each of those things takes time and coordination to install it and a larger workforce to execute it. Modern construction is more complicated and costly as a result.

That’s part of the answer. The fact is, each square foot of skyscraper in 2023 delivers way more value than a square foot of skyscraper a century ago. You have HVAC systems, better elevators, far more wiring and plumbing, etc.

Start making more money weekly. This is valuable part time work for everyone. The best part ,work from the comfort of your house and get paid from $10k-$20k each week . Start today and have your first cash at the end of this week. Visit this article

for more details.. https://createmaxwealth.blogspot.com

Automated construction is a thing, like 3-D printing a house, but very simple, very plain and literally top-down only. They've gotten as tall as two stories with little foundational support.

Layering different materials other than concrete or structures other than 4 walls of concrete with maybe a small window and doors are at least a decade away at best, and involves everything being pre-planned much more extensively than the present.

Anything but poured concrete involves taking materials upwards, securing the materials, sorting the materials and then using the materials. All of that requires balancing, lifting, spatial awareness, etc. Boston Dynamics is working on robots that can do these things, sometimes two at once, but it's a long way off from automated.

Finally, your chart is in price per square foot but let's wrap our heads around the total initial outlays before utilities and drywall. Tens of millions. I would wager that architects and skyscraper construction firms are risk-adverse about new technologies when it comes to that much money.

Earthquake and fire standards get upgraded after every earthquake and fire. That adds to costs. And the higher you go the stricter the the requirements are. And not just for the added height, but the entire building. Plus, going down for parking levels is very expensive.

Weren't the evacuation and safety codes revised again after 9/11? We learn from experience.

There has been a lot of technological change over the years. You won't see many carpenters wielding hammers on a building site these days. They use nail guns. Similarly house frames are not erected on site; they are made in a factory, brought in on a truck, and erected by a crane. Bricks aren't laid on commercial buildings by bricklayers; brick panels made off-site are delivered and bolted into place. Workers don't painstakingly make one bathroom after another in a new hotel from a store of basins and pipes and the rest; complete bathroom units are trucked in and hoisted up by the on-site tower cranes, needing only to have power and plumbing connected. And so on.

Kevin is correct that there has been little adoption of robotics and digital technology on-site, but an ever-increasing amount of the construction takes place in factories. The on-site operation is increasingly little more than assembling all the pre-manufactured pieces correctly. The exceptions are one-off projects such as architect-designed homes and specialised buildings (e.g. hospitals). It's also true that measuring productivity in the construction industry is problematic; trying to identify trends over time or do comparisons between one sector/country and another, even more so.

Why is NYC is a world unto itself, construction-cost wise?

Because it is an extremely expensive island with the highest population density in the country.

The first ensures anything having to do with land is a matter for conflict. The second means everything is more difficult simply because people are all over the place, and many of them will both have nothing to do with your construction and also be impacted by it.

Or were you trying to bait someone in to talking about unions?

Uh no. Not at all. I was just curious. Truth to tell, I wondered if the mafia had anything to do with it.

In addition, I support unions. Even so, I didn't think of them as a factor.

If nothing else, getting concrete onto the site is a challenge. Concrete has to be used within a fixed time after it is mixed. NYC traffic is horrendous, so loads can time out. (NYC builders pioneered pouring and lifting two floors in 24 hours, twice the rate of most cities.) NYC has rules about closing sidewalks to traffic. In most cities, you can just take over the sidewalk and half the street for materials staging and logistics. In NYC, you need to build a "sidewalk shed" to allow pedestrians to pass and deal with the site logistics as best you can. There's also the problem with tightly packed underground infrastructure and neighboring buildings that may share support walls. It can get really complicated quickly.

Building codes, zoning regulations, and permits.

There were very limited building codes until the 70s. Every iteration of the IBC (and its predecessors) has become more stringent, requiring better performance such as energy efficiency across HVAC, glazing, insulation.

Zoning will limit the types of piling and shoring you're allowed to use. They will dictate the number of open spaces and percentage of landscape, require public art work, minimum number of vehicle parking spaces, required loading zone areas, and often trigger a separate community design review. Overlaid, you have environmental reviews, sometimes involving USACE or other federal agencies.

Costs of permits, often based on an annually-adjusted cost per $1000 valuation of construction or per unit of something (square footage, fixtures, etc.), will always increase.

It's really hard to lower the cost of construction by automation or lowering labor involvement. To lower costs of construction many facades utilize panelized systems. Plumbing has switched from copper to PEX. Post-tensioned steel floors result in some cost savings. Mass timber reduces a ton of labor in the field, but it's still relatively new so labor costs will remain high for the time being.

If you really want to lower the cost of skyscrapers you have to accept mass production (copies) of the same design. Do you want that, or would you rather have bespoke structures?

Oh, and during the permit process, you can (will) wait for months before someone actually reviews your permit app. Some jurisdictions allow you to jump the line by paying an extra fee. If there are omissions or errors in the permit, it can throw you back into a queue that sets you back weeks. In the worst jurisdictions, the process is linear and so you're stuck with one review -- structural for instance -- before it'll go to mechanical. And as they say, time = money. You can book subs for X date, but if the permit is stuck, well, costs add up.

The cost of permits is the least of it. The real cost is in the delay, time being money.

I include in the cost of permits, the amount of time and delays as a result of it.

You could have used Chicago. They have a few tall buildings.

Skyscrapers.

No thanks.

I just can’t do heights any more.

Bridges, tall buildings, upper decks of stadiums, even small mountains.

I just can’t focus and I get physically ill.

Construction in general in the US is expensive.

One thing often mentioned is the way construction is done in the US. Here contractors assemble teams as needed so little experience is carried over from job to job. Outside the US contractors keep their teams together from job to job.

Another thing often mentioned is how much citizens can comment on projects. Public comment of one sort or another can require changes or delays which add costs.

Regarding skyscrapers, the taller they get the less floor space is available. The taller the building the wider the supports are at the base so more and more of the cost of square footage is burdened by the cost of the supports.

Sooooo . . . ChatGPT isn't going to solve it in less than 10 years?

The giant cranes now used for skyscrapers were introduced in the sixties and seventies. The steel frames of skyscrapers are now sprayed with insulation for fire protection instead of being layered with sheet rock. Besides these I am not away of any other new technologies being introduced.

That's right. They call those kangaroo cranes, because they were first developed in Australia. They can lift themselves higher and higher as they build their own support tower.

The use of reinforced concrete as opposed to steel girders reduces a lot of the labor costs. You build one form, pour a floor and lift it. The old girder and panel model is out of date. This was originally developed in Cuba where steel was extremely expensive.

"To build a house, you mark out a foundation, dump in some concrete, erect a frame, and then fill it up with stuff."

Yeah, and to play the flute you just blow in the big hole and wiggle your fingers over the little ones. And to create charts in Excel you wiggle your fingers over a keyboard and repeatedly press the button on your mouse while you move it around. Right?

"Beyond that, modern buildings are earthquake proof, flood proof, fire proof, and more efficient—all of which add to the cost of construction."

This *might* be a better explanation. I live in a 100-year-old house that's barely been upgraded at all. So except in the living room (which was upgraded a bit) there's one light fixture in each room and one electrical socket. There was one sink in the kitchen and one in the bathroom. A shower was retrofitted over the tub some time in the 1960s. There's no insulation. The windows were all single pane. The basement leaks in heavy rainstorms. It's earthquake country here but the house isn't bolted to the (hand-poured, crumbling) foundation. And so on.

Point being that an old house is to a modern one as a Model T is to a Honda Accord. And just in case you say "yeah, both cars are made on assembly lines" I'll point out that *assembly lines* are infinitely more sophisticated today (even the ones in Alabama) than cutting-edge ones were in the early 20th Century.

In other words you're just wrong. Yeah, houses are still built (mostly) by hand... though with nail guns and not hammers. But *what* gets built these days takes quite a lot more time. Even without building regulations, permitting, and other "red tape." Nobody wants to buy a 20's-era shotgun shack anymore, any more than they want to drive a Model T from the same era: they just expect more.

It's not " -proof"; they're all "-resistant".

Flood-resistant design is only required if your structure is located w/in a FEMA-designated flood zone.

A lot of jurisdictions have no earthquake-based requirements. Some instead have hurricane-resistant design requirements, instead.

Fire-resistant design is dependent on several factors and not everything is fire-resistant. Typically, it's limited to protection of structural elements, facades (if they're located w/in X-distance of other structures or lot lines) and exit passages.

An interesting thing re high rises: In Hawaii, most of the older residential high rises were built w/o automatic sprinklers (before building codes). Now, many condo HOAs are being forced to grapple with multi-million dollar retrofits as required by law, following one specific deadly fire.

Have to wonder if we are correctly measuring the output or the value of the construction project.

Is the building exactly the same per square foot, or are we producing a more valuable good today? If so, how much more valuable?

How do we measure the value of prevented construction related deaths and injuries?

The stats we use for economic prognostication are fairly limited....often nearly useless to make the broad conclusions that we like to make with data sets by simply assuming that the data is accurate and meaningful.

Certainly for houses, what's built today is VASTLY superior to what was being built even 20 years ago. The CA code is really good now about things like insulation.

I've lived in a variety of CA houses over the years, and you can really see how they get better every twenty years or so, from the (in winter) arctic conditions of a 1900 house to coziness of a 2020 house.

Insulation is an immediate difference, but other house differences include

- safer electrical code (and a LOT more outlets)

- plumbing seems to be better (at least larger diameter pipes), and things like backflow preventers are now mandatory

- fire safety is now a huge deal. And I assume for skyscrapers there is a massive mount of seismic stuff that wasn't required earlier (may have been retrofitted, but does not appear in those early costs)

One issue which may matter is simply that it's much easier (which I assume translates into cheaper) to build in an "empty" zone than in a dense city.

This is at least part of why China has been able to look so good by these sorts of metrics; for many projects they haven't had to deal with the constant grind of things like closing streets, figuring out how to bring in large items through narrow streets, being careful that the crane doesn't knock over nearby buildings, or that digging does not break into the sewer/water/subway/electrical/gas/fiber optic lines, finding somewhere to store materials, having to stop work at sub-optimal times because of noise concerns, and all the rest of it.

My guess is that even in LA (let alone say New York) these things are much worse now than in say the 20s and 30s, which explains part of what we see.

"Why? Shouldn't we expect that productivity gains over that period would make it cheaper to build?"

In most industries those productivity gains comes from scaling economies and repetition. The more you make of something the cheaper it gets to make each unit.

Skyscrapers are one of the few things humans make that are still one offs. With very few exceptions (like the WTC Twin Towers), each skyscraper built is unique. Sure, there are certain aspects of the construction that are applicable to all, but overall, the process from design to opening will be a unique one for each skyscraper in terms of the exact design features, materials used, construction techniques required, equipment needed, personnel needed, etc., so there is very little room for scaling production over the long term (like on say automobiles).

I seem to remember when I was in college in the late 70's, that the architecture students believed the skyscraper to be obsolete. Large, densely populated cities were obsolete. Modern shipping, travel, and communications made these things unnecessary & undesirable. (In 1978!) Why pack people into stifling , noisy, unhealthy places like that?

Skyscrapers are phallic symbols erected by rich shitheads as a symbol of their power. The more expensive they are the better. It's all about conspicuous consumption.

Why build any more?