The golden age of blogs is long behind us, and there's a school of thought that blames Google for this. Specifically, it blames Google for cancelling Google Reader, the app that nearly everyone once used to read blogs.

For some of you, that paragraph makes perfect sense. For others, it might as well be in Greek. So let me explain as briefly as possible.

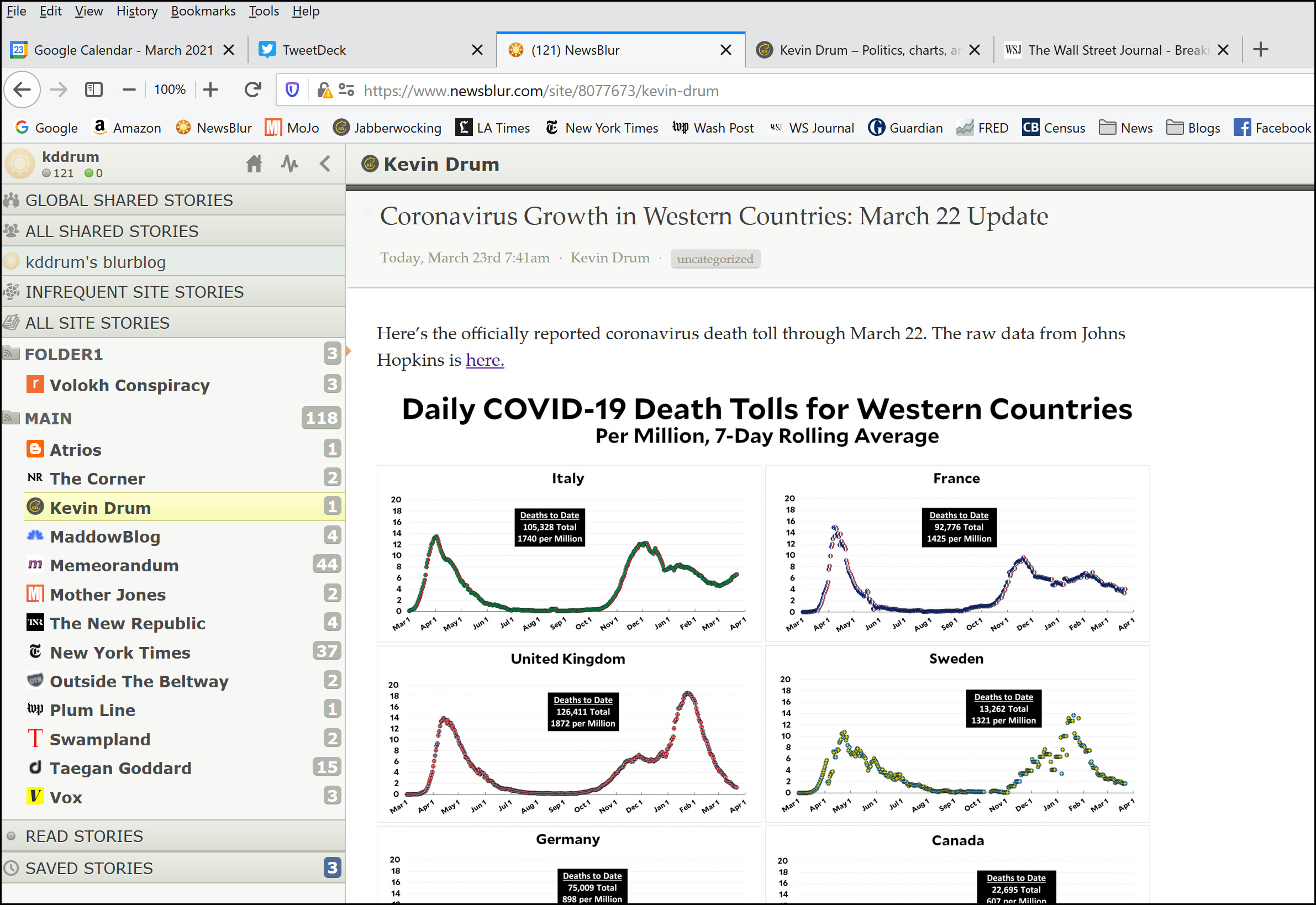

All blogs, including this one, have an RSS feed. RSS is an independent standard that broadcasts the text of a blog (and other forms of web content) in a common format. An RSS reader is an app that pulls in that content and displays it. After the death of Google Reader I switched to NewsBlur, which looks like this:

I use NewsBlur only for blog reading, but there are plenty of other things you can also use it for. As you can see, it keeps track of all the blogs I've told it about and tells me if any of them have new posts since the last time I checked. This is very handy since it means I don't have to scroll through all of them periodically just to see if they've posted anything new.

Anyway. As I said, Google Reader was the de facto standard for reading blogs back in the day, and there was much weeping and gnashing of teeth when it was canceled. But was that responsible for a decline in blog audiences?

I asked that question on Twitter yesterday, and the consensus was "Meh. Maybe." But people also pointed to other things. There was the period when many of the most popular bloggers turned pro. There was the upswing in social media, especially Facebook and Twitter. Maybe those were more at fault.

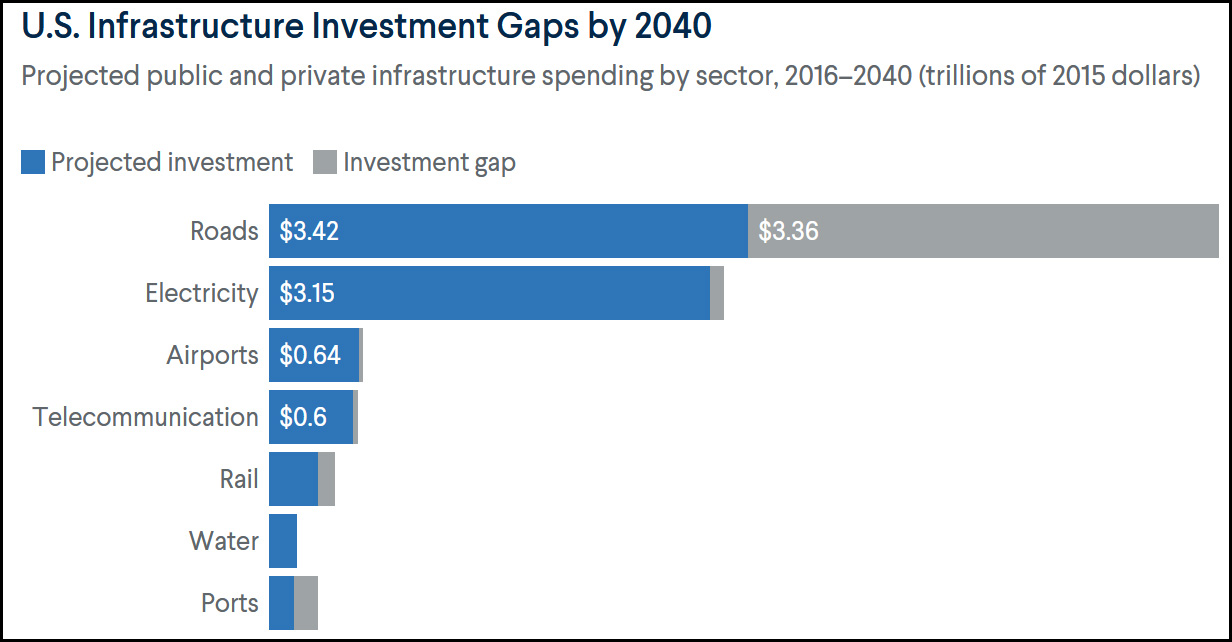

This got me curious in a navel-gazing sort of way. So in bloggy fashion, I went to Google Trends to extract some data that might or might not be a good proxy for blog popularity. Here's a chart showing Google searches for the topic "blog" since 2004:

If we assume that this really does represent blog popularity, we can say a few things about the decline that started in 2009. First, my recollection is that the peak years for bloggers turning pro was around 2005-07. But blog popularity continued to increase for several years after that. So that's probably not the cause of the decline.

Google Reader is an even worse fit. Blog popularity had already been on a downswing for more than three years when Google canceled it in 2013. It obviously can't have been the initial cause of the decline.

Social media is harder to get a handle on. Twitter is an unlikely villain for a downturn that began in 2009, since Twitter just wasn't that popular back then. Facebook, however, fits pretty well and provides a platform for blog-length musings. It's clearly a candidate.

But you can't look at this chart without noticing one other thing: The decline in blog popularity starts almost precisely when George W. Bush left office. It was Bush and the Iraq war that popularized blogs in the first place, so it would be sort of poetic if his departure marked the beginning of the end for blogs. Maybe blogs just lost their mojo when their favorite punching bag flew home to Texas.

Or it might just be a coincidence. Personally I find Facebook the most likely culprit.

But there's one other question left hanging: Google Reader might not have been responsible for the initial decline of blogs, but why was it canceled? It was a pretty low maintenance product and could have easily been kept around. Nobody at Google would even have noticed it. In a similar vein, Facebook and Twitter have reduced their support for RSS even though it requires very little effort to maintain. Why?

The most likely answer to all these questions is that RSS broadcasts content directly to users. There's no way to monetize it, and it cannibalizes users away from platforms that want to be your sole hub for news aggregation. Google wanted its users on Google+, or at the very least finding the news via search, which generated ad revenue. Facebook wanted you to read a news feed full of ads within their walled garden. And Twitter wanted to be the place where news broke first—but only if you were actually on Twitter.

In other words, RSS was a threat to practically every platform that aggregates news since it allowed users to decide for themselves what news they wanted to see—and to see it without passing through a gatekeeper. The best way to eliminate this threat was to eliminate or reduce support for RSS, as Google, Facebook, and Twitter have all done.

Blogs were just collateral damage here. An RSS reader is the only decent way to read a collection of blogs, and with the demise of RSS and Google Reader it became more difficult to follow blogs. Sure, lots of people switched to a different reader, but lots more didn't know how or just never got around to it. And with that, the decline in blog readership accelerated. This was the start of a vicious cycle that opened up opportunities for Twitter, Medium, YouTube, podcasts, Substack, and other platforms that increasingly replaced blogs as the place for web-centric conversation.

Maybe. It's a plausible story, anyway. I just don't know for sure if it's true.