Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through June 5. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Cats, charts, and politics

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through June 5. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Over the past few decades voting laws have become progressively looser. In the early '70s, nearly all voting was done on Election Day, with only 3-4% done via absentee ballot. That number rose slowly for the next 20 years and then skyrocketed beginning in the early '90s:

By 2016 nearly 40% of the electorate voted early. About half of this was accounted for by mail ballots and the other half by early voting during extended hours at polling places. Early in-person voting increased from zero in 1992 to about 19% of all ballots in 2016.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through June 4. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

The new case rate in the US is going down steadily and is now lower than it's been since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020. If this keeps up, our mortality rate should keep dropping too. We just need to get our vaccination rate back up for a while and we should be very close to finally crushing the virus for good, although we still have at least a year of work, maybe more, to inoculate the rest of the world as well.

Every year the Department of Housing and Urban Development performs a Point in Time count of the homeless. On a single day, usually in winter, teams fan out across the country to count the homeless everywhere at the same time. Here are the PIT counts since they began:

Roughly speaking, this total can be broken into three pieces:

There are issues with how PIT counts are done, which means these figures are not unanimously agreed on among advocates for the homeless. They are, however, the closest thing we have to a reliable count across time.

The PIT count is also broken down by cities, which are referred to by the obscurely bureaucratic label "Continuum of Care." Don't ask why. Here are the top five cities in the US:

As you can see, New York and Los Angeles are in a class by themselves, accounting for a quarter of all homeless between them.

Every once in a while an invader cat wanders into our backyard during the night and Hopper goes nuts. She starts yowling at terrific volume and attacking the sliding glass door as if this cat was about to steal her food dish. The cat runs away as soon as we open the door to go out, and that's that.

Until last week, that is, when Hopper suddenly went nuts one morning. We went out and discovered a brown tabby just hanging out next door. He seemed to have no interest in Hopper at all, and eventually she fled. I, of course, went back for my camera and got a picture. Behold the invader cat.

The American economy gained 559,000 jobs last month. The unemployment rate fell to 5.8 percent.

There's nothing special to report about the May numbers. The size of the civilian labor force stayed roughly the same and about half a million people transitioned from unemployed to employed. That's a decent number, though not overwhelming. We still have more than 7 million jobs to go before we reach pre-pandemic levels, so we should do better over the next few months.

Average hourly earnings were up in May by about 3% after you account for inflation. That's good!

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through June 3. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

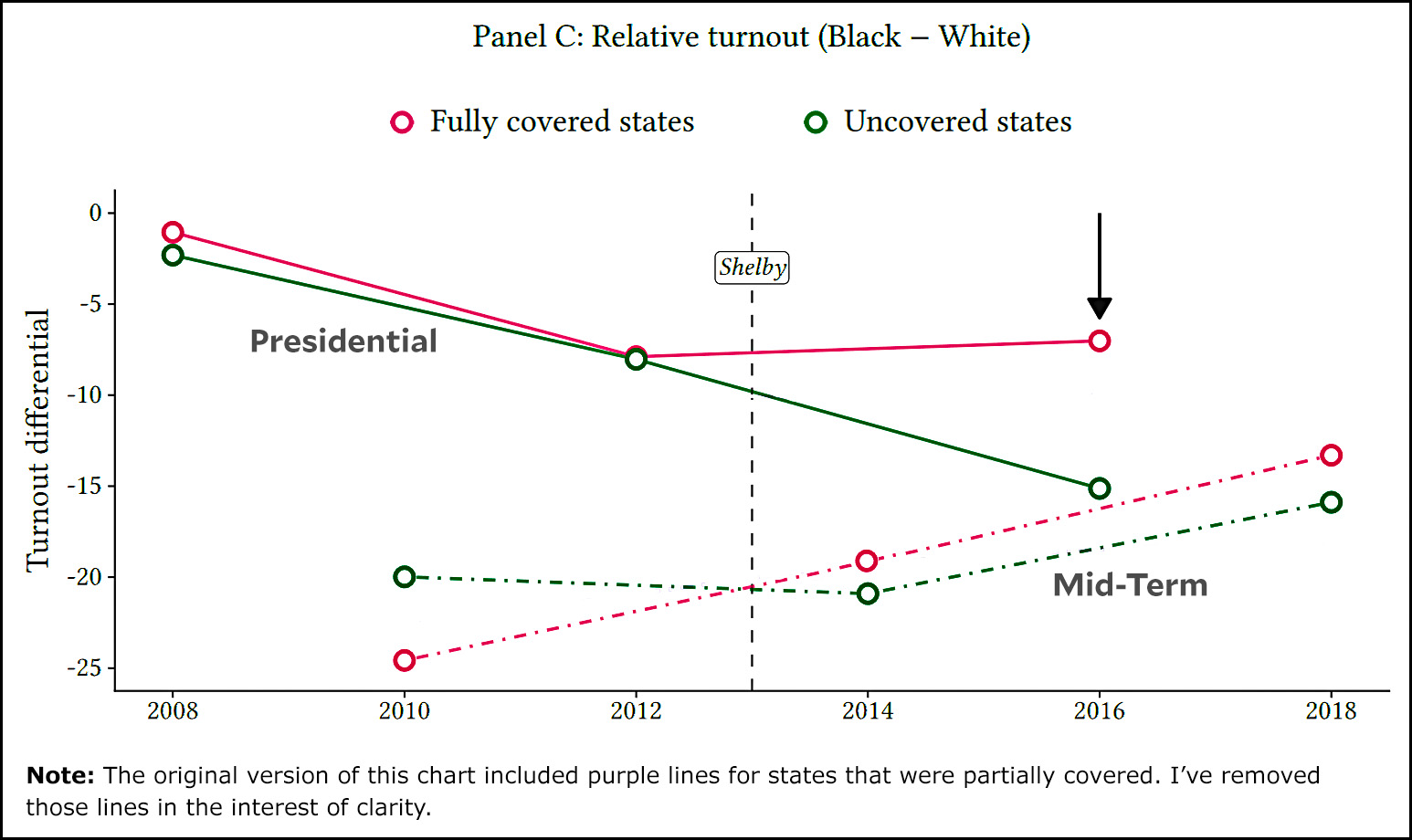

How much do various Republican efforts to suppress the vote actually end up suppressing the vote? The evidence suggests that the answer is "not much," and a recent study provides more confirmation of this. It comes from Kyle Raze of the University of Oregon, who took a look at the effect of Shelby vs. Holder, the Supreme Court decision that overturned parts of the Voting Rights Act and opened the door for states to pass new voting laws without first getting them precleared.

What you'd expect is that in states that previously required preclearance two things would happen. First, they'd rush to pass laws designed to affect Black voting. That happened just as you'd think. Second, Black turnout would therefore decline compared to white turnout. That didn't happen:

This is a little complicated, but here's what the chart shows. In red you have the states that previously required preclearance and were therefore affected by Shelby. In presidential elections, the gap between white and Black turnout did indeed increase by about five points after Shelby was handed down, but it turns out this is no smoking gun. In other states (green), which weren't affected by Shelby, the gap increased even more.

In midterm elections, the gap decreased in states that were affected by Shelby. The gap also decreased in other states, but not as much.

In other words, Black turnout relative to white turnout improved more in Shelby states than in non-Shelby states. All the effort that the Shelby states put into changing their voting laws didn't help them. In fact, it backfired.

As usual, this is one study that takes one particular approach to the data, and it might not be correct. But the methodology seems reasonable and other studies have come to similar conclusions. This is why I'm not all that concerned about the general voting restrictions that red states have been pounding into place ever since the 2020 election. Republicans are doing this in a panic, and they have no idea what will work and what won't. For the most part, they're accomplishing little except pissing off Black voters and encouraging them to turn out in greater numbers.

Unfortunately, the new hotness in red states is to pass laws that allow Republican legislatures to replace election officials if they feel that ballot counting isn't going the way they'd like. That's genuinely banana republic territory, and it's the thing we need to shine a spotlight on.

This is a coast prickly pear cactus highlighted by the midday sun. It grows only in a 20-mile-wide coastal strip that extends from Los Angeles to San Diego in the US and down to Baja California in Mexico. You can, apparently, cook the fruit like a pumpkin and mill the seeds into flour. Handy!

Are you looking for the latest and greatest in lab leak journalism? Check out Katherine Eban's 12,000-word magnum opus in Vanity Fair this month. It is a tale of international intrigue, lies, coverups, dueling scientists, and so much more.

In the end, I'm not quite sure it really changes the conversation, though. For example, Eban dives deep into the fights between US scientists from different parts of the State Department. On one side you had officials who thought that virologists were actively covering up evidence of a lab leak because they didn't want their own research jeopardized. On the other side you had officials who thought the lab-leak folks were presenting evidence so thin it "makes us look like the crackpot brigade."

As one senior government official with knowledge of the State Department’s investigation said, “They were writing this for certain customers in the Trump administration. We asked for the reporting behind the statements that were made. It took forever. Then you’d read the report, it would have this reference to a tweet and a date. It was not something you could go back and find.”

After listening to the investigators’ findings, a technical expert in one of the State Department’s bioweapons offices “thought they were bonkers,” [Chris] Ford recalled.

It's a good piece with tons of detail, but in the end we're left mostly where we started: there's circumstantial evidence all over the place, but no smoking gun on either side. It's not clear if that's likely to change anytime soon.