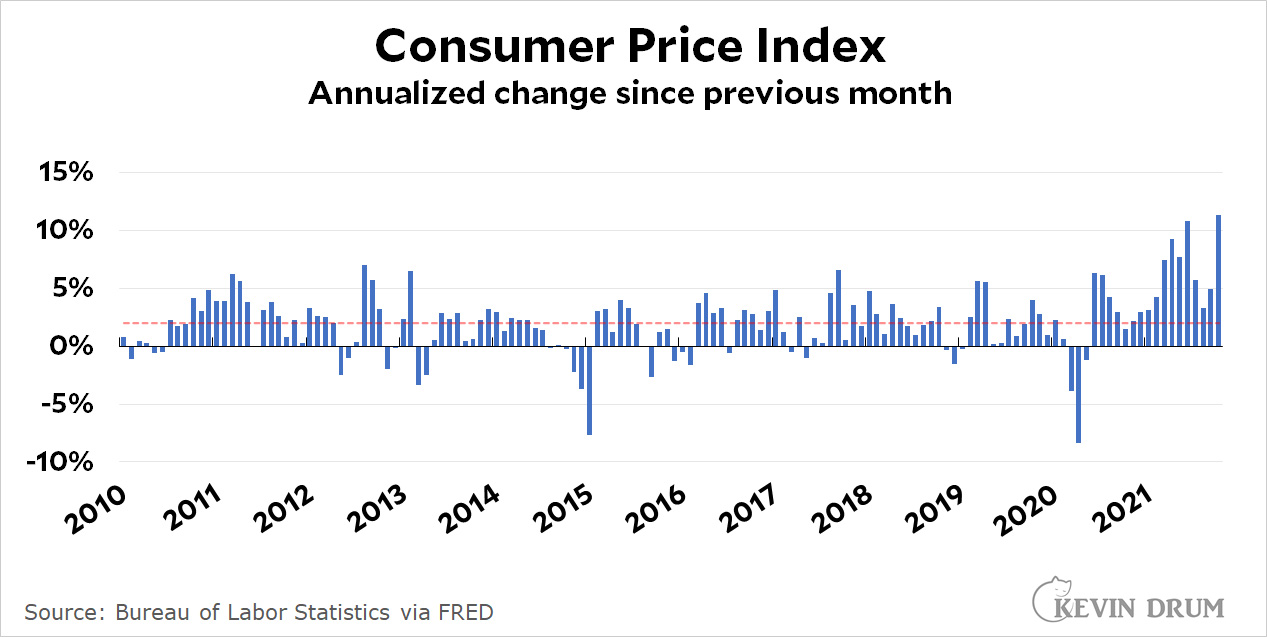

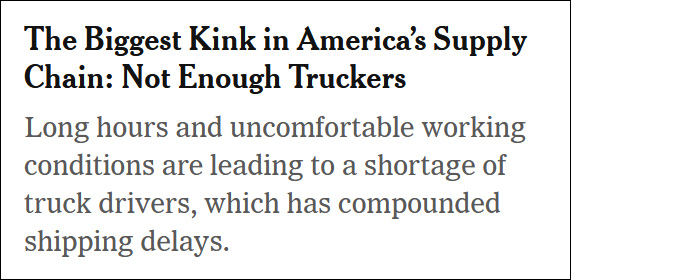

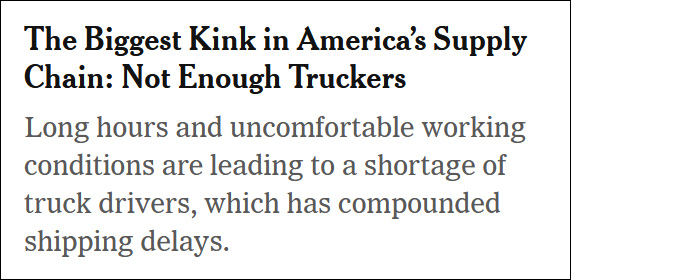

The New York Times helpfully explains the biggest problem with our supply chain these days:

Well, sure. But there's always been a shortage of truckers. You can find a story like this practically every year for the past few decades. In fact, the claimed shortage this year of 80,000 truckers is less than the claimed shortage in many prior years. For example, here's a CNN piece from 2012 claiming a shortage of 200,000 truckers just in the long-haul business.

Well, sure. But there's always been a shortage of truckers. You can find a story like this practically every year for the past few decades. In fact, the claimed shortage this year of 80,000 truckers is less than the claimed shortage in many prior years. For example, here's a CNN piece from 2012 claiming a shortage of 200,000 truckers just in the long-haul business.

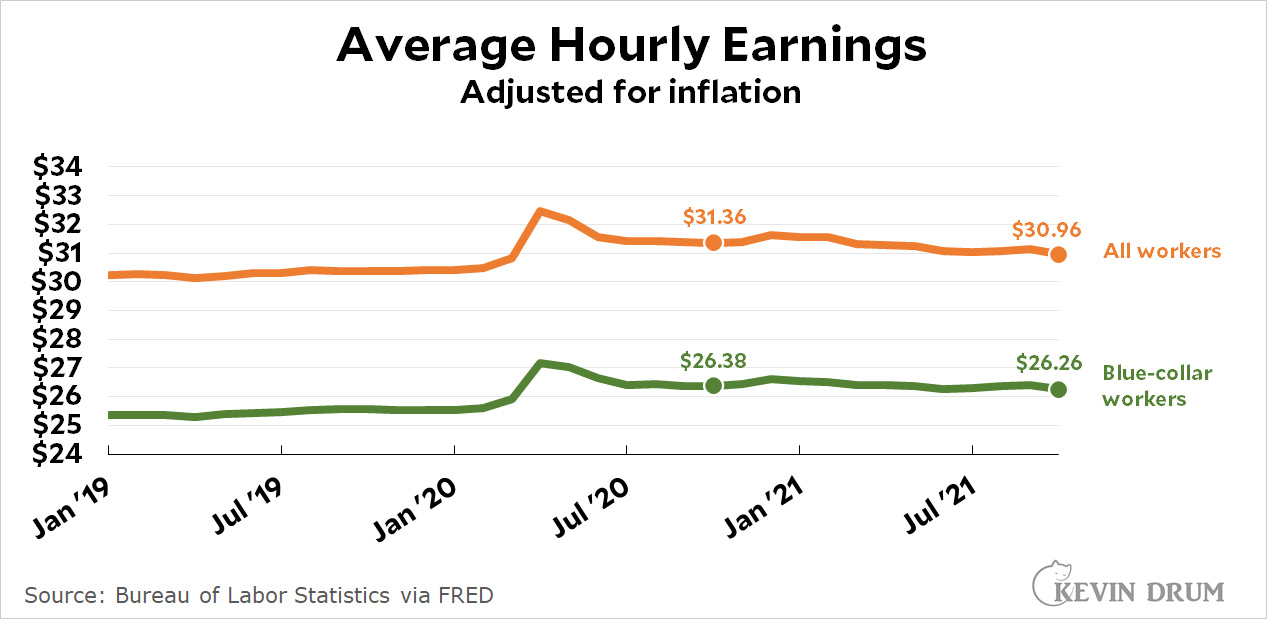

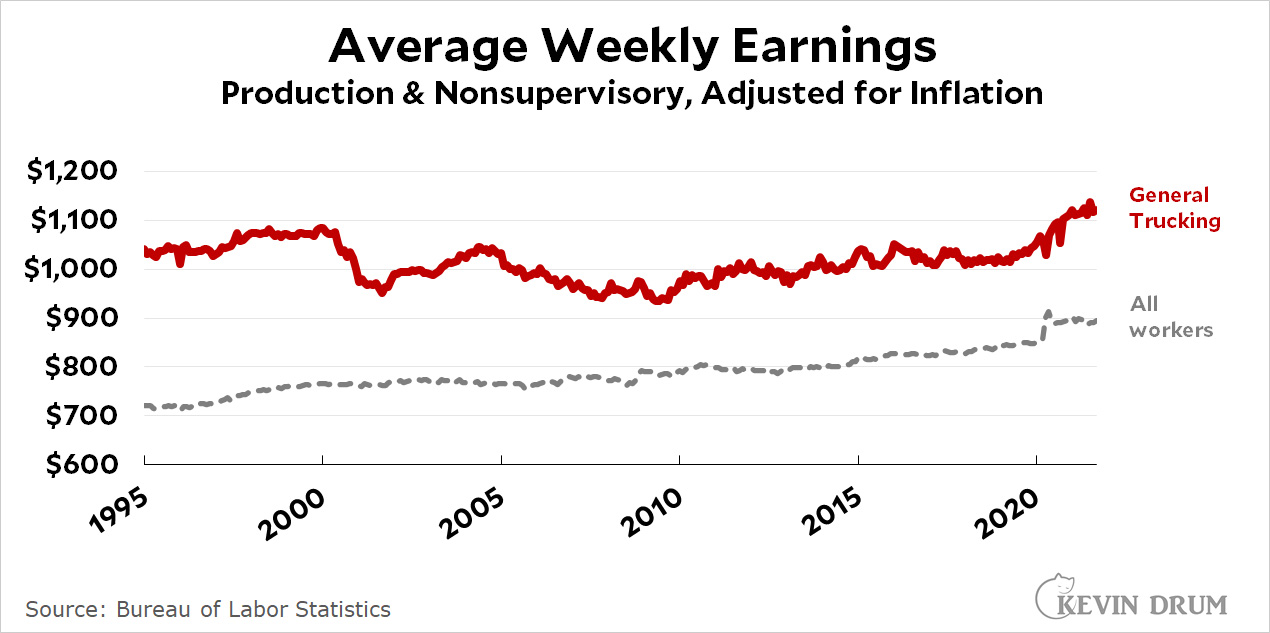

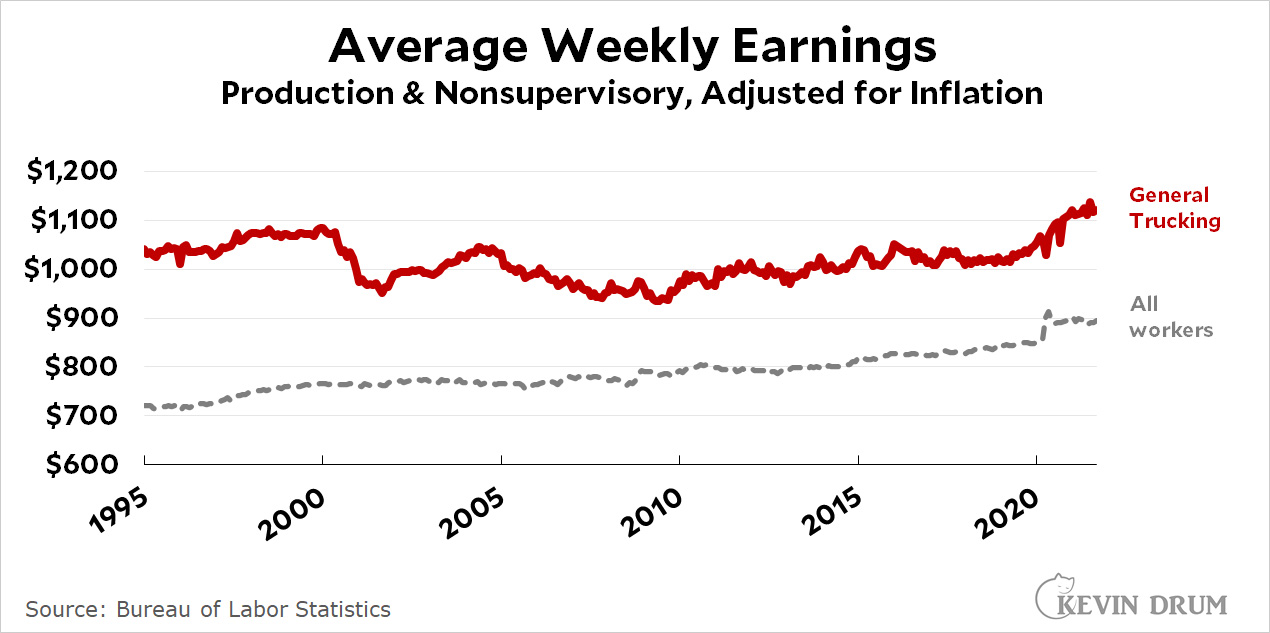

In any case, if there really is a shortage of truckers, it sure looks like no one is bothering to do much about it:

Back in the 1990s, blue-collar trucking jobs paid a little less than $1,100 per week. That figure then declined for years until finally rising a bit above $1,100 during the strong wage growth of the past few years.

Back in the 1990s, blue-collar trucking jobs paid a little less than $1,100 per week. That figure then declined for years until finally rising a bit above $1,100 during the strong wage growth of the past few years.

Conversely, weekly earnings for the rest of the blue-collar workforce rose slowly but steadily during the same time. Roughly speaking, truckers earned about 44% more than other blue-collar workers in 1995 but now earn only 23% more.

So is there really a shortage of truckers? Maybe, but I trust wage data a whole lot more than I trust either anecdotes or claims from industry associations. If real wages are going down, both in absolute and relative terms, there's no shortage. It's all but impossible.

So what's really going on? The specific reason this is in the news right now is that we need trucks to haul away containers from our jammed ports. This means we need to dive a little deeper and look at what it means to be a driver for a dedicated port trucking company, the only ones who are in this business. Ryan Johnson explains one big problem:

I’m fortunate enough to be a Teamster — a union driver — an employee paid by the hour. Most port drivers are ‘independent contractors’, leased onto a carrier who is paying them by the load. Whether their load takes two hours, fourteen hours, or three days to complete, they get paid the same.

....So when the coastal ports started getting clogged up last spring due to the impacts of COVID on business everywhere, drivers started refusing to show up. Congestion got so bad that instead of being able to do three loads a day, they could only do one. They took a 2/3 pay cut and most of these drivers were working 12 hours a day or more. While carriers were charging increased pandemic shipping rates, none of those rate increases went to the driver wages.

There's much more of interest here, but it all comes down to the same thing: money. There are more drivers out there, but the port business has gotten so crappy that it's a money-losing proposition for a lot of these guys. Trucking companies could attract them back with higher wages, but that's considered beyond the pale. As with so many employers, they'll whine and complain and claim to be willing to do anything—except pay more. It's an old story.

UPDATE: Here's another factor, which is yet another subset of "money":