After I got back from lunch this afternoon I checked to see what the twittering classes were twittering about. It turns out that one of their big targets was an essay in Politico by John Harris about the underlying cause of our current political discontent. The problem, Harris says, is that unlike previous periods of turbulence, we don't really have one this time:

The real Civil War was about slavery — at the start, to restrict its territorial expansion, by war’s end to eliminate it entirely. Capitalists opposed to the New Deal knew why they loathed FDR — he was fundamentally shifting the balance of power between public and private sectors — and FDR knew, too: “They are unanimous in their hate for me, and I welcome their hatred.” The unrest of the 1960s was about ending segregation and stopping the Vietnam War.

Only in recent years have we seen foundation-shaking political conflict — both sides believing the other would turn the United States into something unrecognizable — with no obvious and easily summarized root cause. What is the fundamental question that hangs in the balance between the people who hate Trump and what he stands for and the people who love Trump and hate those who hate him? This is less an ideological conflict than a psychological one.

Harris is taking a lot of flak for suggesting that there's no big underlying cause to our current unrest. So let's examine the two most obvious candidates: race and money, with a focus on white men since they're the ones who seem most discontented.

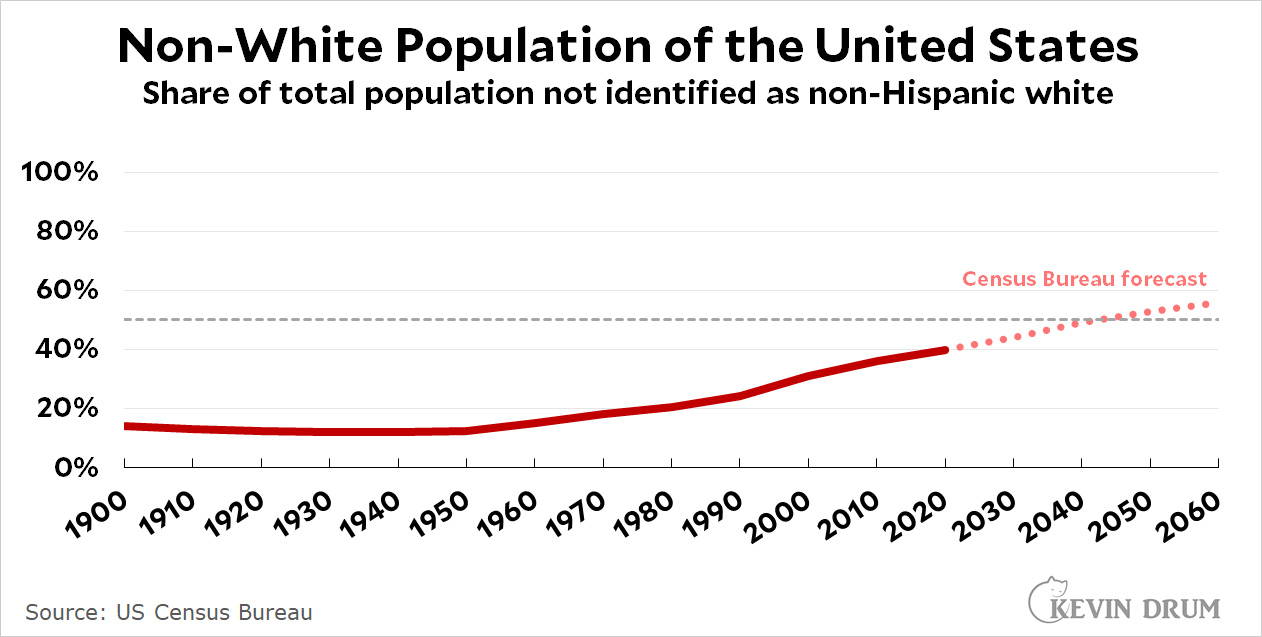

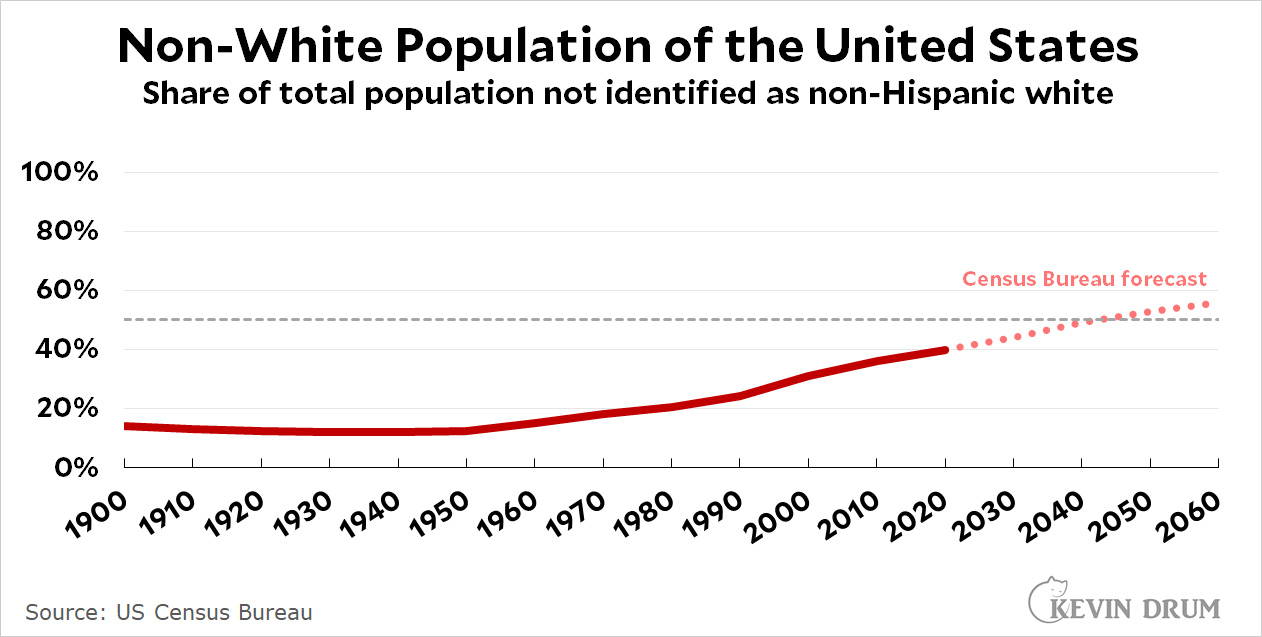

Let's look at race first. Here's the non-white population of the country:

Are white people petrified about becoming "a minority in their own country"? Many of them probably are. But the rise of the non-white population has been on nearly a straight-line trajectory since 1950. Why would it suddenly turn into a huge source of discontent around 2000? One possibility is that it simply hit a critical mass: it was only when the non-white population rose to about a third of the total that white people began to notice they were increasingly not the majority skin color anymore.

Are white people petrified about becoming "a minority in their own country"? Many of them probably are. But the rise of the non-white population has been on nearly a straight-line trajectory since 1950. Why would it suddenly turn into a huge source of discontent around 2000? One possibility is that it simply hit a critical mass: it was only when the non-white population rose to about a third of the total that white people began to notice they were increasingly not the majority skin color anymore.

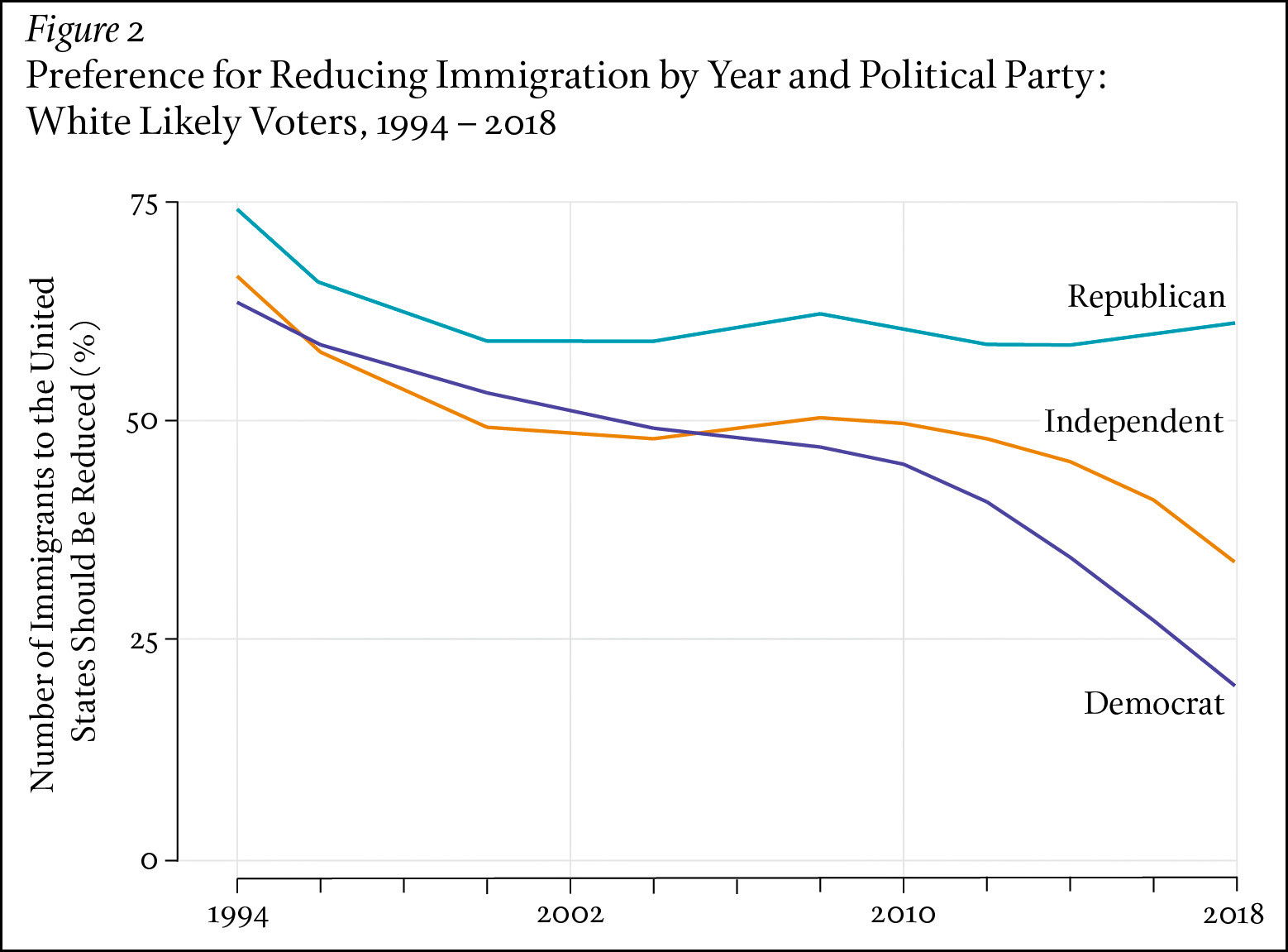

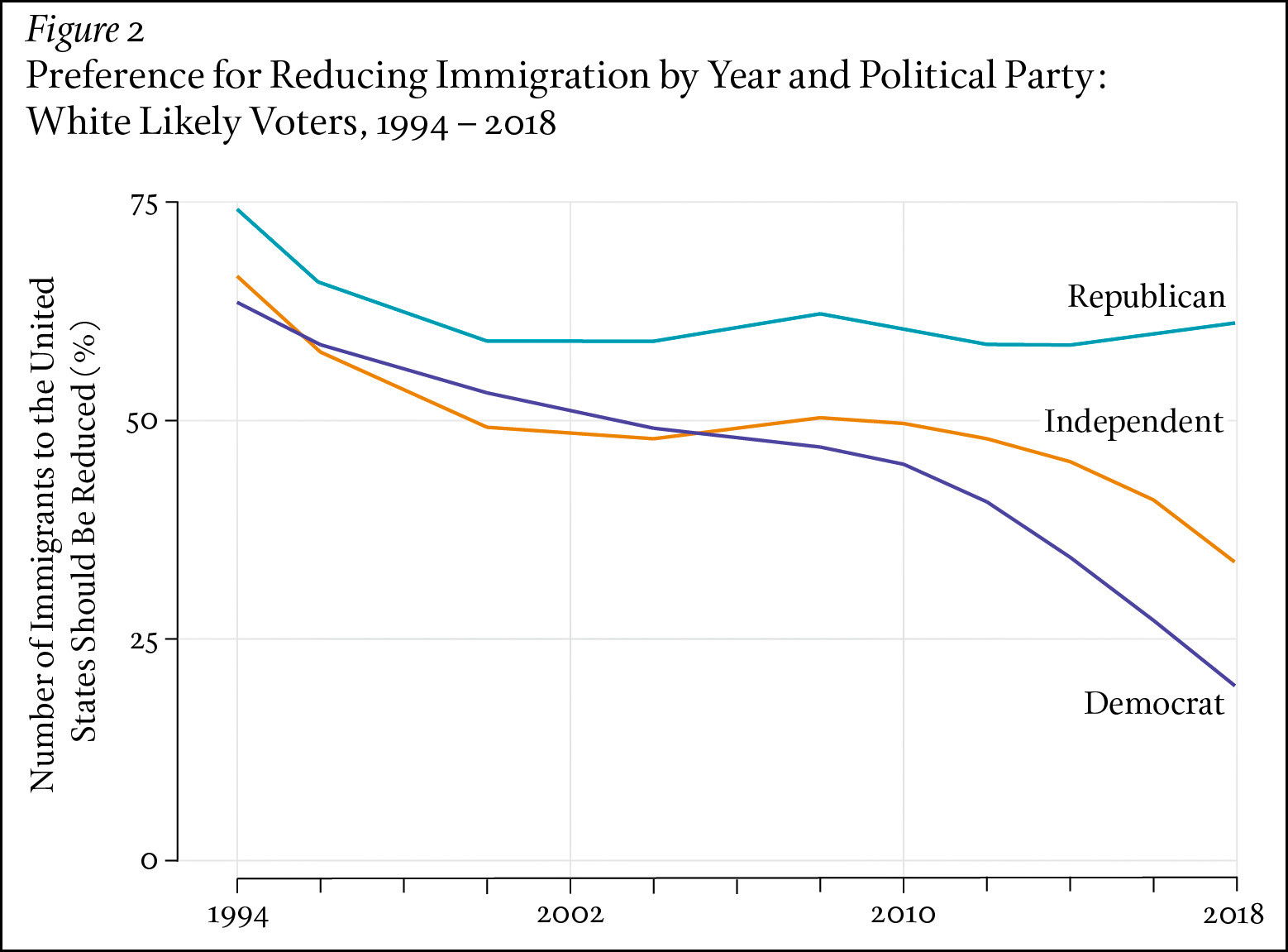

Immigration angst is another racially-fueled concern. How do Republicans feel about that?

There's nothing much going on here. Republican dissatisfaction with immigration dropped in the '90s and has been hovering around 60% since 2000. Those are high numbers, but they haven't changed much.

There's nothing much going on here. Republican dissatisfaction with immigration dropped in the '90s and has been hovering around 60% since 2000. Those are high numbers, but they haven't changed much.

Here's a direct measure of white racial resentment over the past few decades:

It went up a bit during the Obama years and then fell back down in 2016. Taken as a whole, nothing here suggests that racial resentment has been growing more intense lately—although the data doesn't yet cover the 2020 election, which took place after the George Floyd murder and the summer BLM protests.

It went up a bit during the Obama years and then fell back down in 2016. Taken as a whole, nothing here suggests that racial resentment has been growing more intense lately—although the data doesn't yet cover the 2020 election, which took place after the George Floyd murder and the summer BLM protests.

Overall, it's hard to conclude that race and immigration have played huge roles in whatever it is that's eating us. It's obviously been an issue throughout the entire history of the nation, but the evidence suggests that, as an underlying cause, it's no more an issue now than it's ever been.

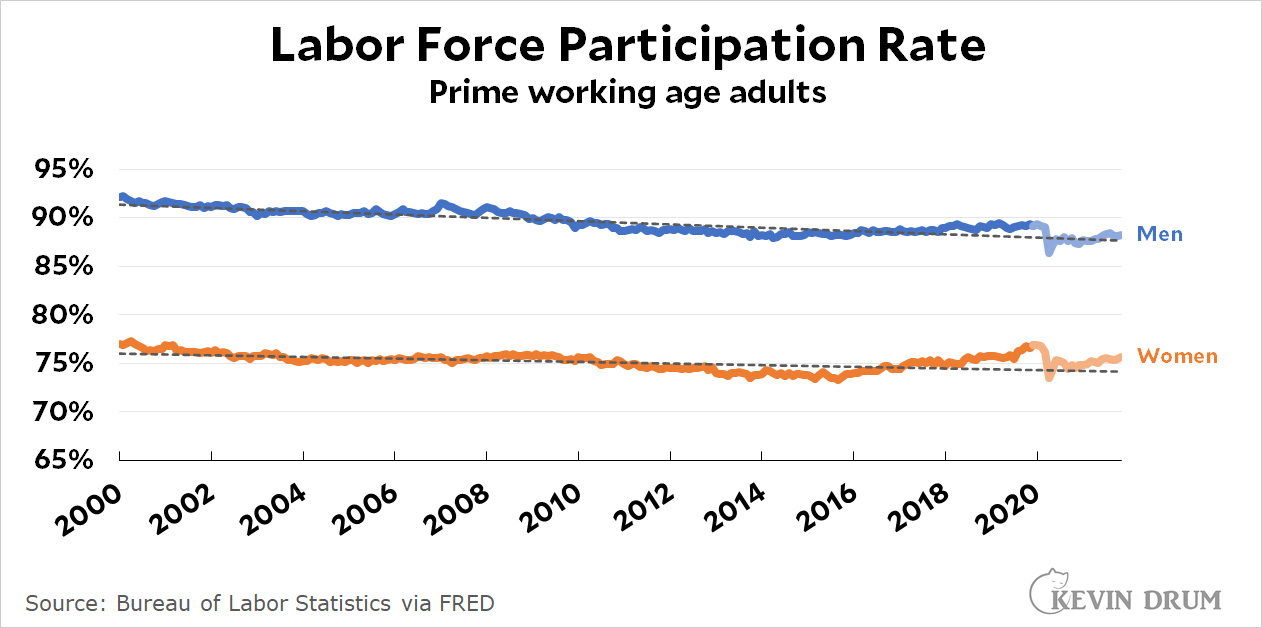

Now let's take a look at money. For starters, did China take all our jobs away? There's no question that this happened to some extent during the 2000-2010 period, but how much? Here's the labor force participation rate for prime working-age men:

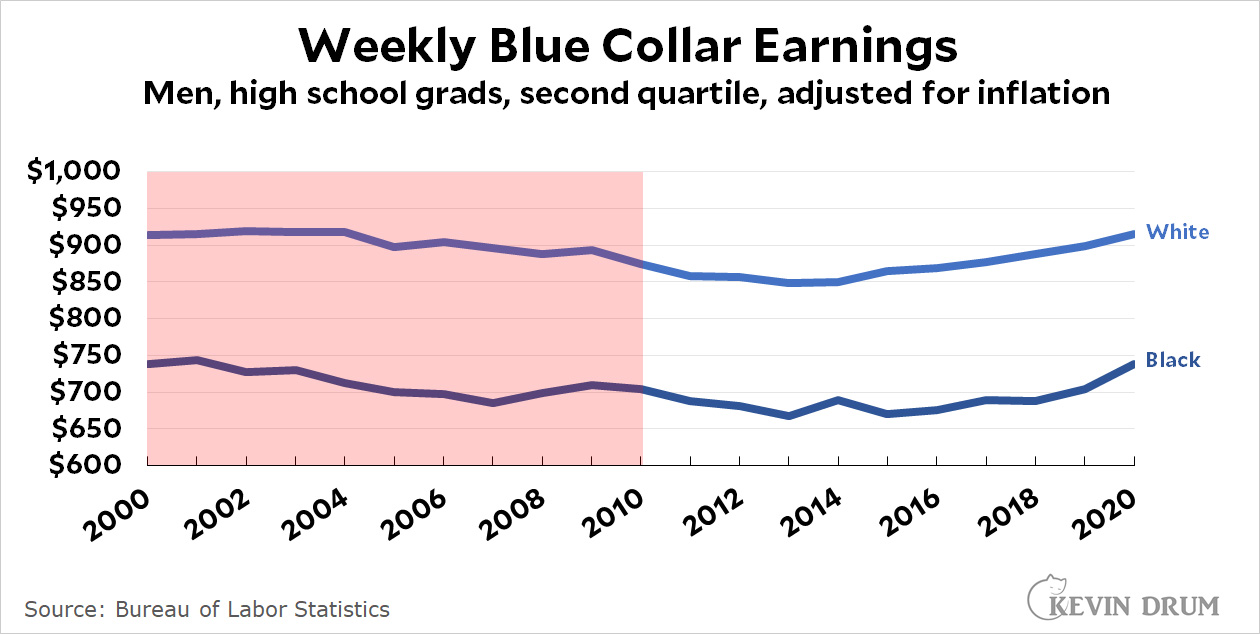

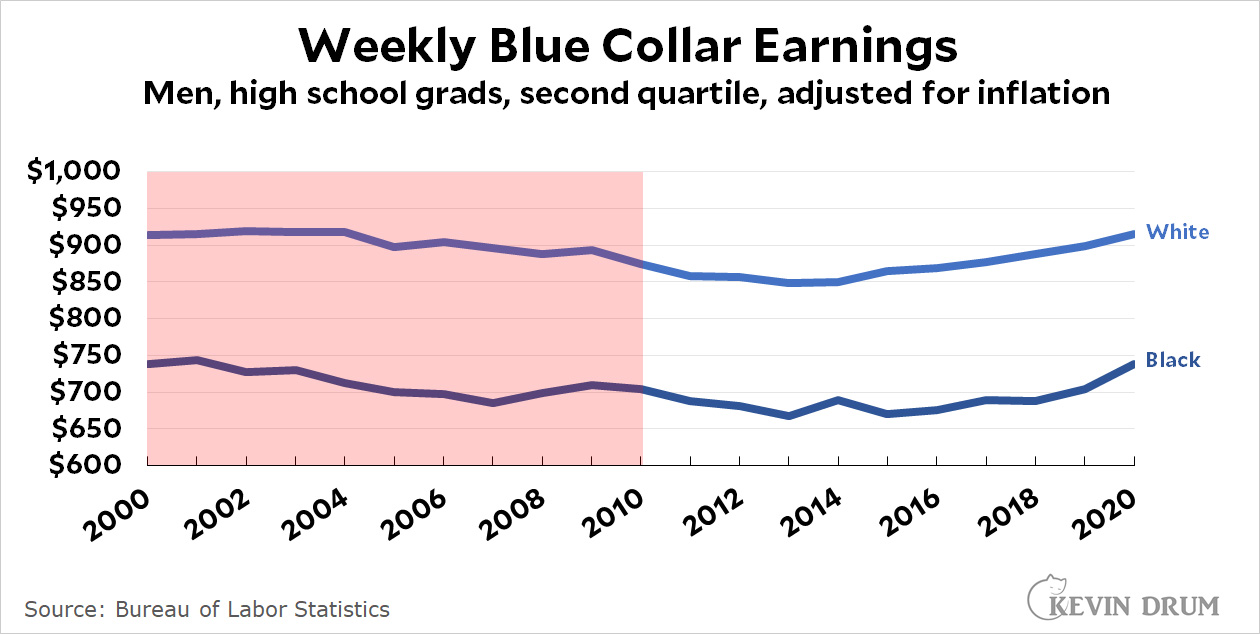

The participation rate has been slowly declining for half a century, and nothing special happened during the aughts. Still, maybe pay dropped dramatically? Let's check:

The participation rate has been slowly declining for half a century, and nothing special happened during the aughts. Still, maybe pay dropped dramatically? Let's check:

This chart shows the famous white working class (white, no college, second quartile earnings) and it turns out that their earnings dropped a few percent during the aughts but that's all. The Great Recession did some more damage, and then they recovered by 2020.

This chart shows the famous white working class (white, no college, second quartile earnings) and it turns out that their earnings dropped a few percent during the aughts but that's all. The Great Recession did some more damage, and then they recovered by 2020.

But did they lose ground to Black men, thus stirring up some racial animus? Nope. They were $176 ahead of them in 2000 and $177 ahead in 2020.

Overall, the money theory is similar to the race theory: there are some things here that aren't great—fewer men working, flat wages—but they're part of trends that have been in place for decades. Nothing special has happened over the past 20 years.

The conclusion here is hard to avoid: neither racial animus nor worries about jobs and the economy seem to have recently skyrocketed among large numbers of white Americans. It's hard to believe that either of these things, on their own, are what's torn the country apart. There must be something else at work.

But what?