Remember the great worker shortage? It's why there are so many job openings going begging. But where did all the workers go? Nobody seems to know.

Perhaps the explanation is simpler than we think. Maybe it's just that a whole lot of people retired during the pandemic:

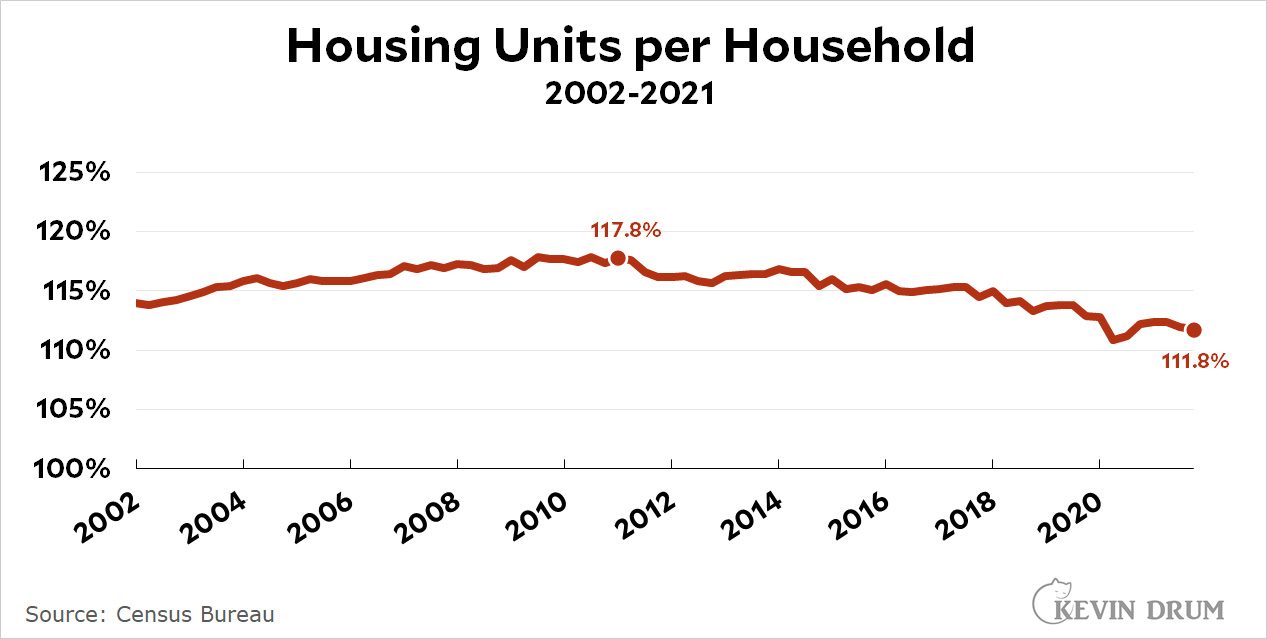

That's from Miguel Faria-e-Castro of the St. Louis Fed. The red line represents how many people "should" have retired and the blue line represents how many people actually did. This was done in August 2021, and by now the excess is probably up to 3 million or so.

That's from Miguel Faria-e-Castro of the St. Louis Fed. The red line represents how many people "should" have retired and the blue line represents how many people actually did. This was done in August 2021, and by now the excess is probably up to 3 million or so.

Faria-e-Castro speculates the the uptick in retirements is due to (a) fear of infection and death, and (b) assets such as homes and stocks rising in value, which made it more feasible to retire.

I'd add another possibility, There were probably a fair number of people who were maybe 62 or 63 at the start of 2020 and then got furloughed or let go entirely when the pandemic hit. They took a look around and decided that by the time businesses started hiring again they'd be 63 or 64 and would have a really hard time finding a new job. So they reassessed their finances and decided that with a little bit of scrimping they'd be OK. Why not just retire now?

But here's another thing. I decided to take a look at a different measure of retirements, namely the number of people applying for Social Security benefits. Here's what it looks like:

This is not the same thing as total retirees, but you'd still expect to see a significant uptick if more people really are retiring. And yet there's nothing. Literally nothing. If you extend the 2017-19 trendline, it passes perfectly through the 2020-21 datapoints. There's not even a hint of an increase.

This is not the same thing as total retirees, but you'd still expect to see a significant uptick if more people really are retiring. And yet there's nothing. Literally nothing. If you extend the 2017-19 trendline, it passes perfectly through the 2020-21 datapoints. There's not even a hint of an increase.

I dunno. Faria-e-Castro got his data from the monthly Current Population Survey, which ought to be the best source. So why doesn't anything show up in the monthly Social Security signups? And why does the CPS data show an uptick starting in January 2020? If it's pandemic related it shouldn't start until April at the earliest.

It is a mystery.