Here is everything you need to know about the price of crude oil.

Month: February 2022

A 1-foot rise in sea level equals hundreds of billions of cubic feet of water

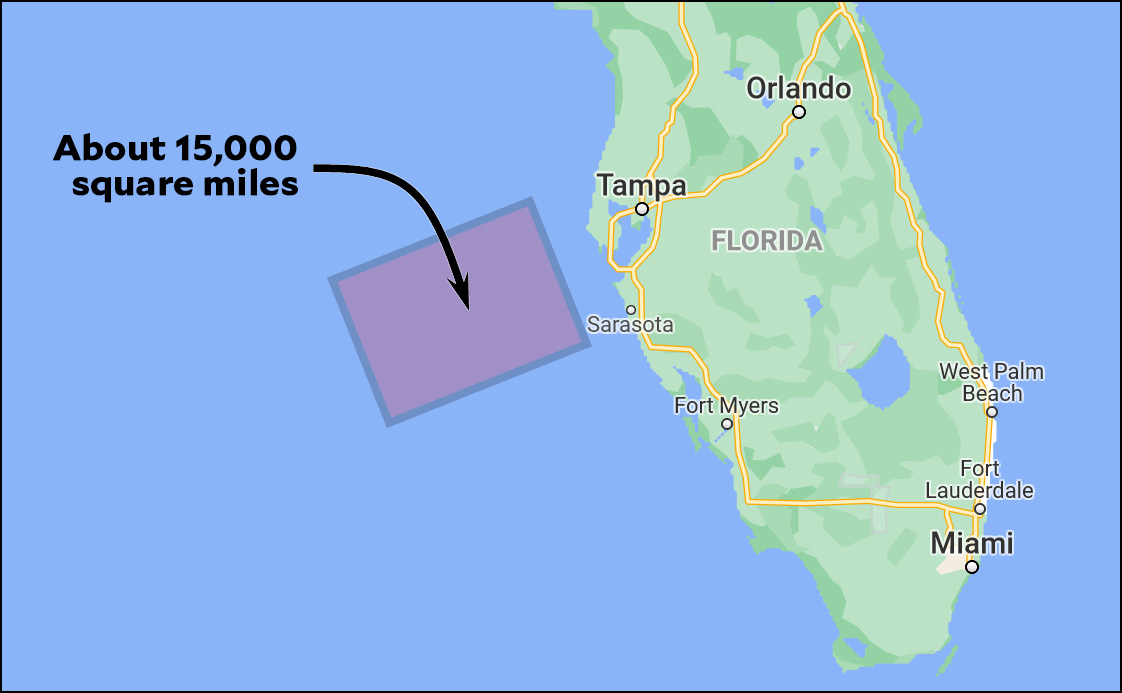

A new study from NOAA says that sea level is likely to rise about a foot by 2050. A foot may not seem like much, but that's only because you're not looking at it right. Consider this:

The study says that sea level will rise about 16 inches in the Gulf Coast. I've chosen Tampa as a photogenic example and marked off the nearby area of the ocean. If 15,000 square miles of ocean increases by 16 inches, that's about 500 billion cubic feet of new water, give or take a few hundred billion. So when a big hurricane churns its way into western Florida, it's got a whole lot more water to push into Tampa Bay.

The study says that sea level will rise about 16 inches in the Gulf Coast. I've chosen Tampa as a photogenic example and marked off the nearby area of the ocean. If 15,000 square miles of ocean increases by 16 inches, that's about 500 billion cubic feet of new water, give or take a few hundred billion. So when a big hurricane churns its way into western Florida, it's got a whole lot more water to push into Tampa Bay.

These numbers are made up just to give you an idea of what this means. When you think about sea level you should think about flooding. And when you think about flooding you should think about the total volume of water likely to be slammed into your coast. A small rise in height creates a prodigious increase in water volume, and volume is what matters when Cat 5 winds come calling.

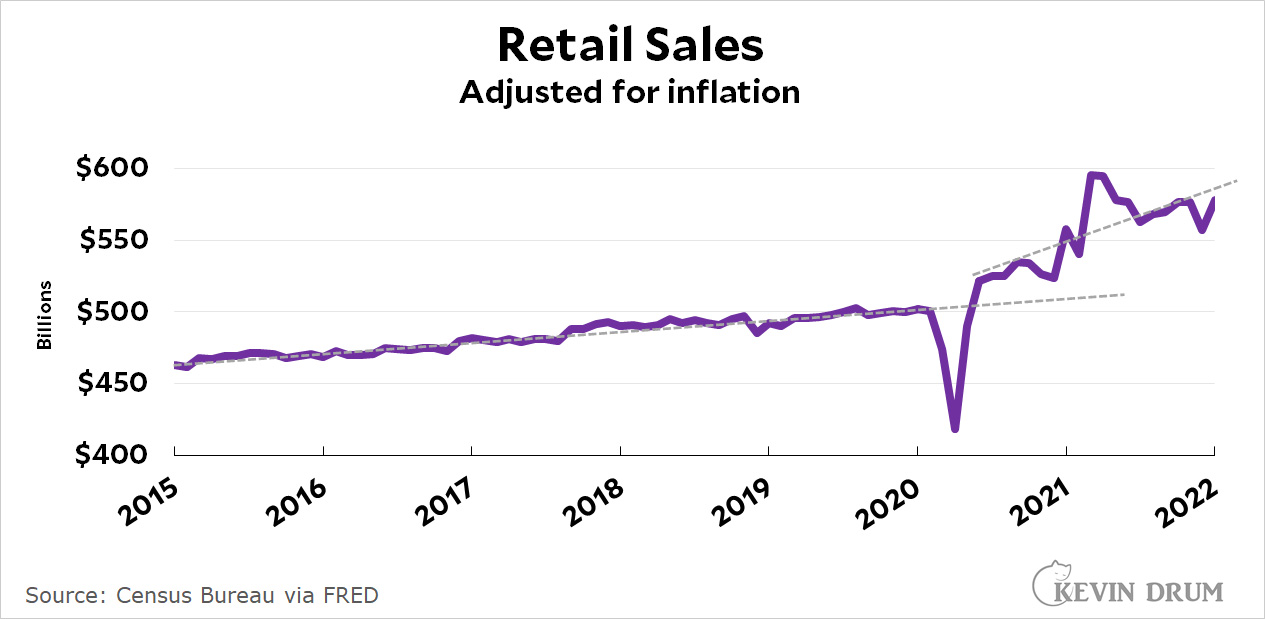

After a weak December, people are back to spending, spending, spending

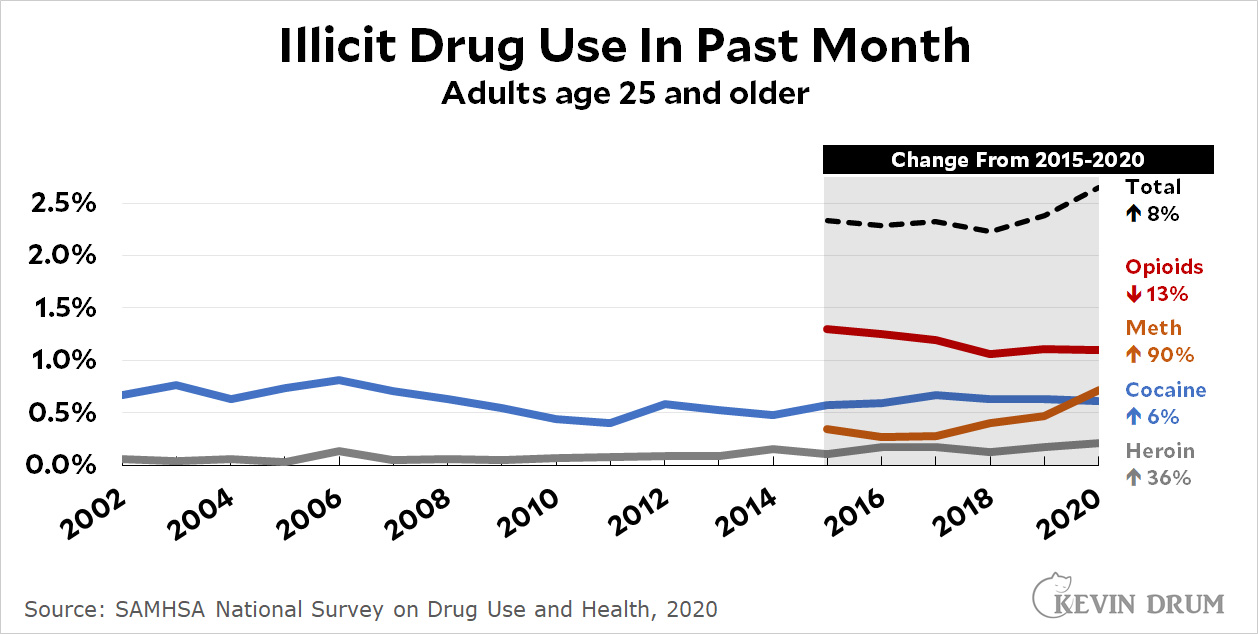

Raw data: Drug use and overdose deaths

Illicit drug use (aside from marijuana) has been steadily falling among teenagers over the past 20 years. But what about adults? Here are the stats from SAMHSA for the four most common drugs:

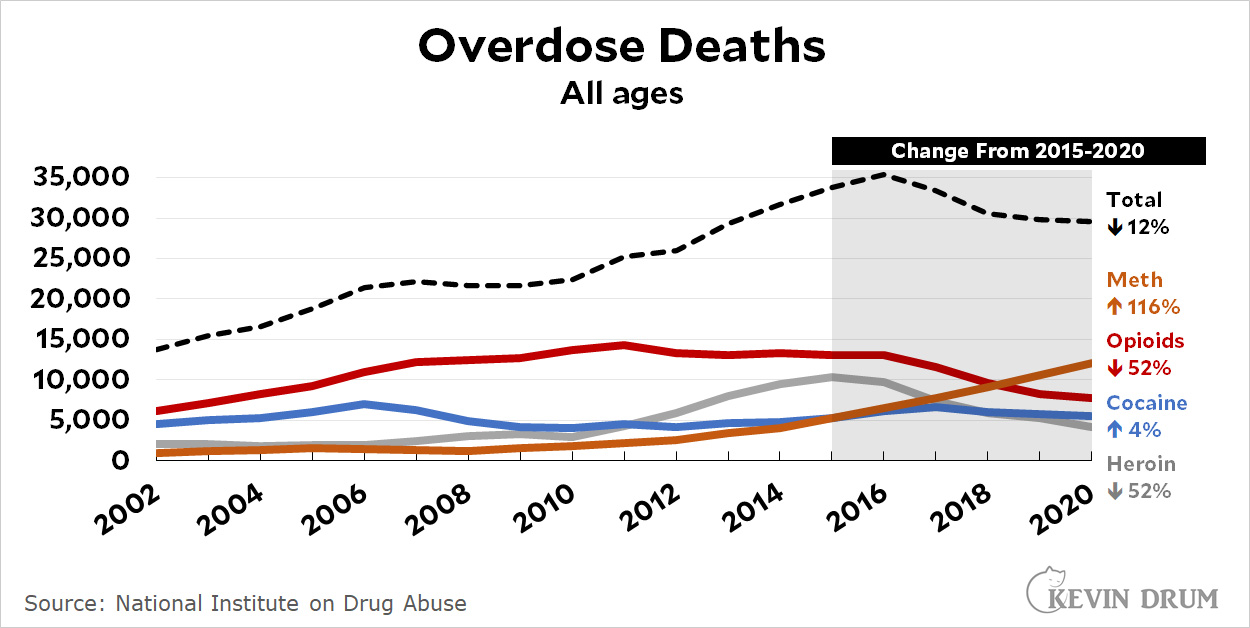

Generally speaking, serious drug use has been fairly steady over the past five years, though meth is up a lot. Here are overdose deaths:

Generally speaking, serious drug use has been fairly steady over the past five years, though meth is up a lot. Here are overdose deaths:

That doesn't look right, does it? Overall overdose deaths are down 12%. Where's the skyrocketing rate of overdose deaths that we all hear so much about?

That doesn't look right, does it? Overall overdose deaths are down 12%. Where's the skyrocketing rate of overdose deaths that we all hear so much about?

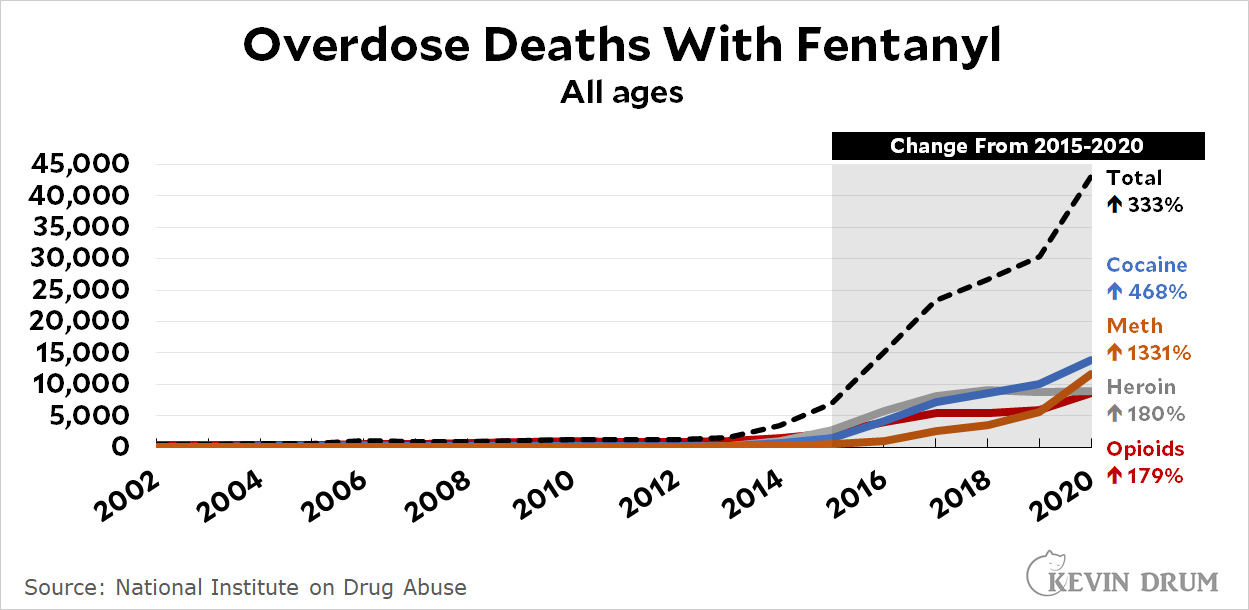

It's a trick. The chart above is only for pure versions of the drugs. Here are overdose deaths for the same drugs mixed with synthetic opioids, which mainly means fentanyl:

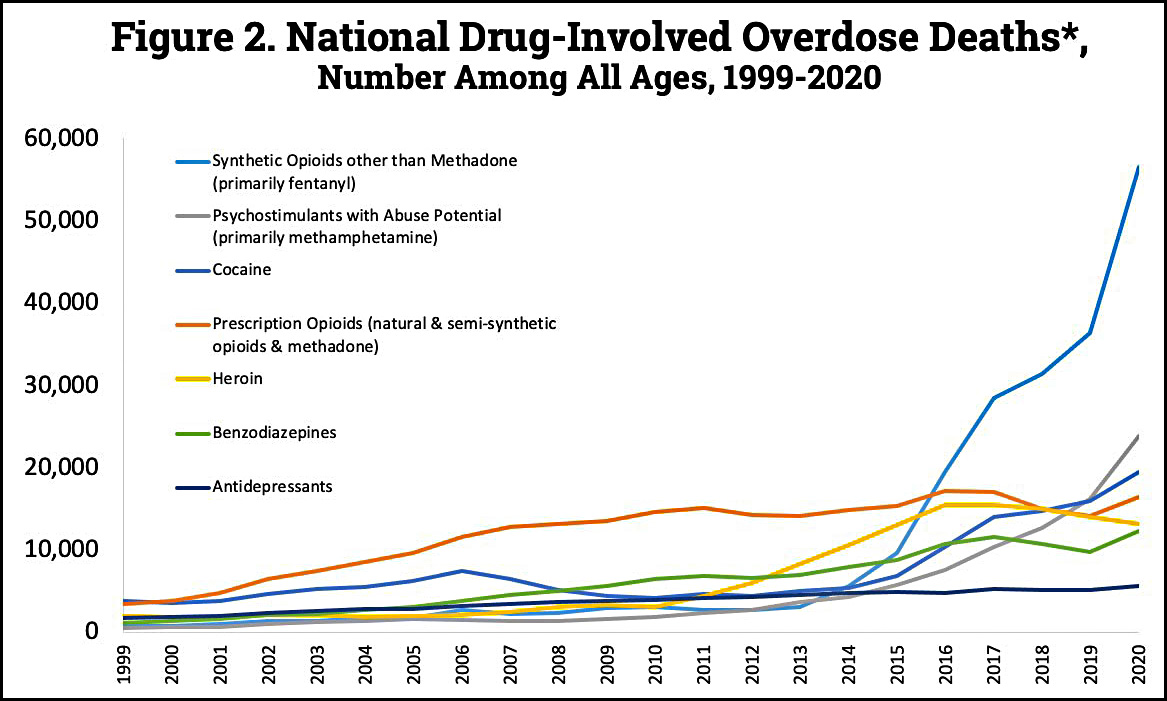

This is nearly the whole overdose crisis. Drug use itself is relatively steady, and overdose deaths are down. The problem is with the fraction of drugs that are laced with fentanyl. Here's a NIDA chart showing all overdose deaths:

This is nearly the whole overdose crisis. Drug use itself is relatively steady, and overdose deaths are down. The problem is with the fraction of drugs that are laced with fentanyl. Here's a NIDA chart showing all overdose deaths:

In 2015 fentanyl accounted for only about 5,000 overdose deaths. Today it's about 55,000. That's not the entire story: meth and cocaine deaths are both up too. But without fentanyl we have only a problem, not a crisis.

In 2015 fentanyl accounted for only about 5,000 overdose deaths. Today it's about 55,000. That's not the entire story: meth and cocaine deaths are both up too. But without fentanyl we have only a problem, not a crisis.

NOTE: The year-to-year data for drug use and overdoses is very noisy. In order to produce reasonable numbers for the change over 2015-2020, I compared the average of 2019-2020 to the average of 2015-2016. That smoothed things out a bit and eliminated a few wild looking outliers.

Lunchtime Photo

To the cool and pragmatic engineering mind that dominates modern society, today's image poses no threat. It's just another crooked, poorly composed snapshot of nothing in particular. There are millions like it stored on cell phones and digital cameras in every state.

But this very surface mediocrity—because it so effectively limns the artist's true intent—makes this image almost performatively transgressive. Just a hair's breadth below the surface, but no less obfuscated to the engineer for that, is a biting commentary on man's relationship to nature—signified by the unseen dog that we are advised in italicized, underlined, capitalized type to "BEWARE OF."

Beware of nature! Everything in this picture privileges human choices: straight lines, sharp focus, fossil fuels, private property protected by barbed wire.

But the photographer playfully—and bravely—lets us in on the joke by maintaining the "accidental" crookedness of the composition, even though we all know how easily it could have been corrected by the engineer's own software, which deconstructs the entire scene into millions of mimetically identical pixels. So why wasn't it?

And how should we react to all this? The unpretentiousness of the surveillance camera on the right reminds us to be careful: it's not art itself that's important, but our socioemotional reaction to art. And we are always being watched—not by the engineer, who doesn't really care, but by those few who have both the sophistication and the polysemous aesthetic sensibility to disdain the engineer's discursive worldview. So never betray yourself to them by letting on that you think this image is anything other than a crooked, poorly composed snapshot of nothing in particular.

New study shows lead in water causes higher levels of juvenile delinquency

A team of researchers recently released a new study of lead and crime based on differences in the lead levels of well water and municipal water in Wake County, North Carolina. This study has two important aspects that make it unusual, but I'll get to that later. First off, here's a brief description.

It turns out that Wake County has excellent records of water service at the residential parcel level starting in 1998. This means that it's possible to find out which families got well water and which got municipal water. This can then be linked with lead testing results among children, which Wake County also has. Long story short, well water had higher lead levels, which means that children who drank well water had blood lead levels about 11% higher than those who drank municipal water.

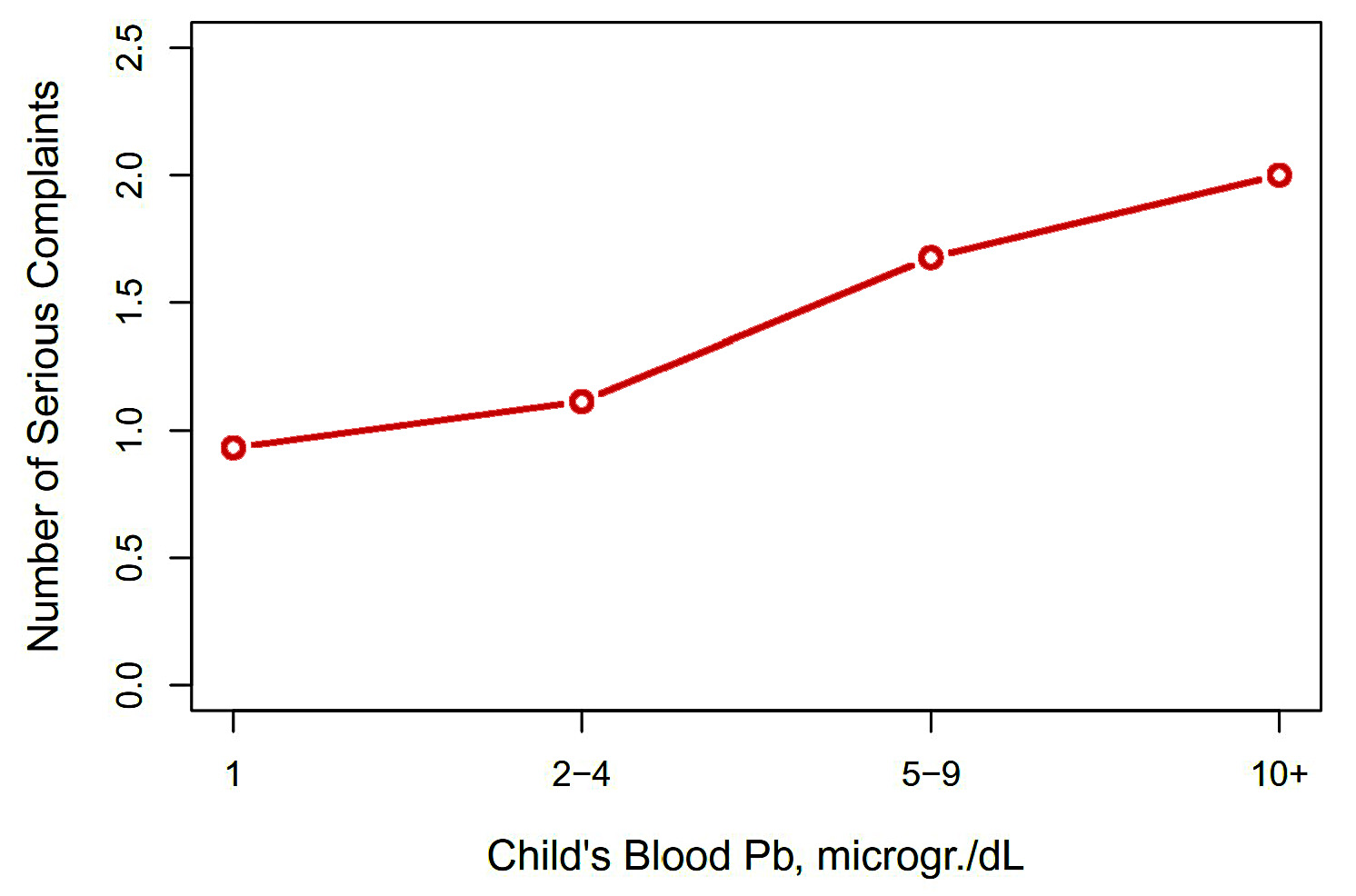

Next, these children can be linked to records of juvenile delinquency later in life. After a fair amount of interesting statistical jiu jitsu, the researchers concluded that higher lead levels produced higher levels of juvenile delinquency. For example:

This chart shows that as lead levels increase, so did the number of serious complaints against the children. The authors produced several different results based on different statistical techniques, and all of them show a significant association of high lead levels with high levels of juvenile delinquency. Their primary estimate is that those relying on private wells had a 21% higher risk of being reported for any delinquency and a 38% increased risk of being reported for serious delinquency after age 14.

This chart shows that as lead levels increase, so did the number of serious complaints against the children. The authors produced several different results based on different statistical techniques, and all of them show a significant association of high lead levels with high levels of juvenile delinquency. Their primary estimate is that those relying on private wells had a 21% higher risk of being reported for any delinquency and a 38% increased risk of being reported for serious delinquency after age 14.

So far this seems familiar. As we all know, there are lots of studies showing that lead exposure in small children produces antisocial behavior later in life. But have you figured out the two aspects of this study that make it stand out? All the clues are in the description above.

First, and easiest, is that the results show significant effects even below the usual testing threshold of 5 mg/ul. The effects aren't huge, of course, but they do confirm that even low levels of lead exposure produce negative cognitive effects. Most studies can't do this.

Second, and most important, this is not an ecological study. In an ecological study you compare groups. For example, you might look at when unleaded gasoline was adopted in each of the states and then compare that to crime levels in those states 15 years later. The group you use might be countries, states, neighborhoods, counties, or anything else you can get data for.

This is all well and good, but ecological studies have limitations. The biggest one is that when you compare large groups you never know for sure if there are hidden variables that make your correlations spurious. There are lots of ways of controlling for this, and if you have lots of ecological studies using lots of different groups—as we do with lead and crime—it makes it pretty likely that the results are genuine.

Still, what you'd really like is to study individuals. For example, a famous study at the University of Cincinnati followed children starting at a young age and tested them regularly. That's a prospective study, and it confirmed at an individual level that more lead produced more crime.

There are almost no studies like this, which makes the North Carolina study especially valuable. Using administrative records, the authors were able to follow individual children from well water to blood lead levels to juvenile delinquency.

So there you have it: yet another study of lead and crime that's produced the usual results in yet another way. What's more, there are two experienced criminology professors among the authors, in addition to the usual shady bunch of economists and environmental professors. The criminology community is catching on. Hooray!

John Durham throws yet more chum into Fox News waters

In the New York Times, Charlie Savage reports on the latest Fox News hysteria over John Durham's investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election. Based on a court filing on Friday, conservatives ran wild with claims about alleged spying on the Trump White House. But there's a problem:

Upon close inspection, these narratives are often based on a misleading presentation of the facts or outright misinformation. They also tend to involve dense and obscure issues, so dissecting them requires asking readers to expend significant mental energy and time — raising the question of whether news outlets should even cover such claims. Yet Trump allies portray the news media as engaged in a cover-up if they don’t.

This is all part of the Michael Sussmann case. Sussmann had presented the FBI with information tying Donald Trump to a Russian bank, and Durham's original indictment alleged that Sussmann told the FBI he wasn't acting on behalf of anyone else. He was just being a good citizen. In a new court filing, Durham outlines some of what he says he knows about what Sussmann did:¹

The Indictment alleges that Sussmann lied in that meeting....In fact, Sussmann had assembled and conveyed the allegations to the FBI on behalf of at least two specific clients, including (i) Rodney Joffe, a technology executive at a U.S.-based Internet company called Neustar, and (ii) the Clinton Campaign.

Sussmann’s billing records reflect that Sussmann repeatedly billed the Clinton Campaign for his work on the Alfa Bank allegations....The Indictment also alleges that, beginning in approximately July 2016, Joffe had worked with Sussmann, Fusion GPS, numerous cyber researchers, and employees at multiple Internet companies to assemble the purported data and white papers.

In connection with these efforts, Joffe exploited his access to non-public and/or proprietary Internet data. Joffe also enlisted the assistance of researchers at Georgia Tech who were receiving and analyzing large amounts of Internet data in connection with a pending federal government cybersecurity research contract. Joffe tasked these researchers to mine Internet data to establish “an inference” and “narrative” tying then-candidate Trump to Russia. In doing so, Joffe indicated that he was seeking to please certain “VIPs,” referring to individuals at Perkins Coie and the Clinton Campaign.

The Government’s evidence at trial will also establish that among the Internet data Joffe and his associates exploited was domain name system (“DNS”) Internet traffic pertaining to (i) Spectrum Health, (ii) Trump Tower, (iii) Donald Trump’s Central Park West apartment building, and (iv) the Executive Office of the President of the United States (“EOP”). (Joffe's employer, Neustar, had come to access and maintain dedicated servers for the EOP as part of a sensitive arrangement whereby it provided DNS resolution services to the EOP. Joffe and his associates exploited this arrangement by mining the EOP’s DNS traffic and other data for the purpose of gathering derogatory information about Donald Trump.)

There's additional stuff about concerns that there was an awful lot of traffic from Russian-made YotaPhones around both the White House and Trump Tower, but let's skip that for now since it's just more of the same. The peculiar thing about all this is that it's completely gratuitous. It demonstrates that Sussmann worked with Joffe, but Sussmann has never denied it. His defense is that he was up front about that with the FBI and never lied to them. So why bother presenting any of this stuff?

What's more, it's not clear if anything in this narrative was illegal. The Georgia Tech folks were using public DNS data to help a military research organization analyze a 2015 Russian malware attack on the White House’s network, and nobody suggests they were acting illegally. Durham does suggest that Joffe obtained the White House DNS logs surreptitiously, which would be illegal, but Joffe claims it was an open part of the malware investigation. And all of this took place during the Obama presidency anyway, so nothing from any DNS searches of the White House could have anything to do with Trump. And Joffe has never been charged with anything.

Finally, there's this: the court filing has to do with Durham's effort to force Sussmann to get a new attorney because his current one has a supposed conflict of interest. That has only the very thinnest, multi-step connection to Joffe. So the entire melodramatic narrative about Joffe is completely superfluous. There's really no reason to include it except as a way of throwing vague, Hillary-related chum to the right-wing conspiracy theorists even though Durham never claims that either Hillary or her campaign had anything to do with Joffe.

¹I have replaced all references to "Tech-Executive-1," "Law Firm-1," etc., with actual names since we know who all these people are.

If you make a ton of money, why not quit young?

Sean McVay is the wunderkind head coach of the LA Rams. He got his job five years ago at the age of 30 and has since led the formerly mediocre Rams to two Super Bowls, losing the first and winning the second.

So now he's 36 and he's been a head coach for five years. But he says he's considering retirement:

The Rams were only a handful of hours removed from a Super Bowl LVI celebration that extended into Monday morning when coach Sean McVay said two words with potentially alarming implications for their future: “We’ll see.” That was McVay’s response to The Los Angeles Times when asked whether he would return to coach the Rams next season.

The obvious initial reaction to this is wtf? McVay is 36, he's been a head coach for only five years, and he's thinking of retiring? What a wuss.

And yet, I've always wondered why it is that more people in super high-paying professions don't do this. Football is a great example. If you play in the NFL for five years and make, say, $10 million or more, why not quit? You're set for life, so why take the chance of playing another decade and risking long-term injuries?

I suppose the answer is that the kind of person who makes it to the very top level of a profession is generally the kind of person who loves their work. They love football. They love being a lawyer or a surgeon. They love writing. They love making music. Etc. In fact, maybe obsessed is a better word.

Still, you'd think there would be at least a fair number of people like this who'd do what McVay is saying he might do.¹ People who make enough to satisfy their own material desires, whatever they might be, and then just quit in their 40s. But maybe there are. I wonder how we could find out?

¹Though I don't think he will.

Economics for daily life

A PhD student in Sweden asked a bunch of Swedish economists which concepts they thought ordinary people should understand in order to manage their own affairs better. Here are the results:

The only concept that got anything like a positive response was opportunity cost. Understanding of interest and marginal concepts got a sort of meh response, and all the others were so low that basically no one thought they were very useful in regular life.

The only concept that got anything like a positive response was opportunity cost. Understanding of interest and marginal concepts got a sort of meh response, and all the others were so low that basically no one thought they were very useful in regular life.

I'm not so sure myself that an understanding of opportunity costs would be very useful. It's one of those things that I suspect most people understand innately. Ditto for interest. Everyone knows that interest means you pay more than the base price for an item in return for the privilege of paying over time. And most common forms of interest—mortgages, credit cards, auto loans—come with pretty understandable descriptions of the gory details. As for marginal concepts, I dunno.

On the flip side, I would have put risk and sunk costs higher. I think there are plenty of people who could benefit from having it hammered into them that higher return always comes with higher risk—which means you really could lose a lot of money.¹ Likewise, people could benefit from taking sunk costs more seriously, although I'm a little curious about what effect that would have in practice.

What else? Apparently not a single Swedish economist mentioned any of the concepts of behavioral economics, which surprises me. I won't try to construct a list, but surely there at least several findings of behavioral economics that many people could benefit from knowing.

¹Although it's true that the people who could benefit from this advice are the least likely to pay attention to it. That's very frequently the case, though, and it shouldn't stop us from trying.

The FTC says romance scams have increased 230% in five years. Really?

According to the FTC, romance scams have skyrocketed over the past five years:

Do you believe this? Do you believe that the number of romance scams has increased 230% and the money amount has increased 500%—in just the past five years? I don't. Come on.

Do you believe this? Do you believe that the number of romance scams has increased 230% and the money amount has increased 500%—in just the past five years? I don't. Come on.

In fact, even the FTC doesn't. Way down in footnote 2, they tell us that the vast majority of frauds aren't reported and refer us to a paper on the subject:

Less than 3 percent of victims complained to a government entity....Less than 1 percent complained to a state Attorney General or other state authority or to a federal agency.

This is such a tiny number that it means the number of fraud complaints is all but useless as a guide to the actual number of frauds committed. If the number of people who were scammed stayed exactly the same, but the share of people who complained about romance frauds rose by just a tiny bit, from 0.5% to 1.5%, it would account for the entire increase reported by the FTC. So the real answer could plausibly range from 0% to 230%. Who knows where the truth really lies?

Data is data, and I'm always happy to see more. But meaningless stuff like this is what produces misleading factoids that bounce around the country forever. The FTC should know better.