The modern Republican Party has two main branches. The first is the social conservative branch, which cares about abortion, guns, sex, and so forth. The second is the business branch, which cares mostly about things like taxes and regulations.

Likewise, there are two main branches of conservative legal theory. The first is originalism, which says the Constitution should be interpreted in the way the framers originally understood it. Social conservatives rely heavily on originalist interpretations of the Constitution for obvious reasons: the Constitution was written more than 200 years ago, at a time when virtually everyone was socially conservative by modern standards. Originalism is almost guaranteed to produce socially conservative results.

The second branch of conservative legal theory is the Law and Economics movement, which applies economic reasoning to the law and relies on things like cost-benefit analysis, calculations of consumer welfare, and financial efficiency. It's important because, surprisingly, the Constitution isn't especially conservative when it comes to economics and regulation: Article I gives Congress plenary authority over taxation while the interstate commerce clause gives Congress broad authority over business regulation (and has almost from the beginning). This means that business conservatives need something besides originalism, and that's where Law and Economics comes in. It took shape beginning in the late '70s, and by now about half of all federal judges have attended one of the two-week seminars on the subject held by the Manne Economics Institute for Federal Judges.

All of this throat clearing is in service of a simple point: both of these legal theories are fairly easy to understand and explain. What's more, to most people they make sense. There are lots of problems with originalism below the surface, but the notion that original intent matters is pretty persuasive if you don't know about those problems. Likewise, it also makes sense that you should understand economic consequences if you're going to make law in the realm of economics.

Now, then, let's compare that to Dahlia Lithwick's defense of liberal lawmaking in a recent interview with Ezra Klein. Apologies for the long excerpt, but it's key to the point I'm going to make:

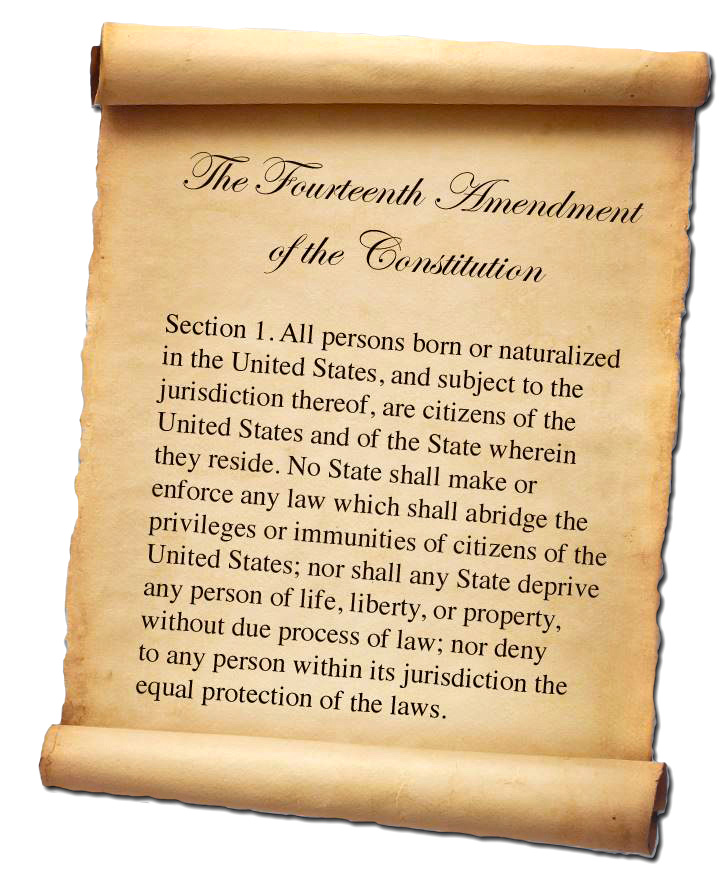

There’s a really, really robust set of rights that is not in the Bill of Rights. It’s lashed to the sort of liberty interests that are fleshed out with the 14th Amendment.

There’s a really, really robust set of rights that is not in the Bill of Rights. It’s lashed to the sort of liberty interests that are fleshed out with the 14th Amendment.

And this is a set of rights, and it’s so important to understand this, and in some sense, so frustrating the Democrats at those Ketanji Brown Jackson hearings didn’t argue this. They’re actually definitional when you were trying to think about what it meant to emancipate former slaves, because if you were former slaves and suddenly you were free, all of the free speech rights in the world and all of the right to bear arms in the world, even using a militia clause, all of those rights are meaningless if you do not have, fundamentally, bodily autonomy and family autonomy.

And so when you look at the drafting of the 14th Amendment and so much of this history, I just want to point to Peggy Cooper Davis, who has done amazing scholarship. Try to put meat on the bones of what it meant to truly be free. And what they were doing when they were thinking about the sort of liberty interest protected by the 14th Amendment that the rest of the Constitution didn’t get at, it was the idea that if somebody can rape your wife, you are not free. If families could be separated, if your children could be sold into slavery over your objections, you were not free.

If husbands and wives were treated as chattel and they were economic instrumentalities, but they were not, in fact, a family unit, they were not free. And there’s amazing, heartbreakingly beautiful language about trying to enforce that idea that the cornerstone of freedom is the ability to define what a family is, to marry who you love, to raise children as you see fit.

And if this all sounds still like peanut butter and cotton candy, I would just say that the whole line of cases that follows that Myers, Pierce, a whole bunch of cases that have to do with how your children are educated, how they are raised, in some sense, it has its apogee in Loving v. Virginia, the anti-miscegenation case that says you cannot be free if you cannot construct the family that you want to construct.

And all of that becomes this kind of unenumerated rights substantive due process. It’s so fundamental to what it meant to be free, and to suggest that, oh, you know Griswold v. Connecticut was invented out of plain air by these weird hippie justices who wanted to give people the right to use contraception is to ignore all of that framing language and ideology about what the 14th Amendment sought to protect in terms of what your liberty interests were.

Etc.

Unless you're already ensconced in the legal world, I assume you didn't really understand a word of that. Right? And that's not a hit on Lithwick—although she could have done better. The fact is that the liberal theory she's talking about here—using the language of substantive due process and "bodily autonomy"—is neither simple nor persuasive to the ordinary schmoe. Nobody ever explains it well at a layman's level. Conservatives say, "Abortion isn't mentioned anywhere in the Constitution and it was illegal almost everywhere before 1973." In response, liberals stutter and stammer and reel off a few hundred incomprehensible words about a complicated and unintuitive legal doctrine.

So do I have a point to make here, as I promised? Indeed I do: we liberals need to talk prettier. Constitutional law is just one area in which liberals, regardless of whether they're right or wrong, speak in an opaque, convoluted language that ordinary people can barely make sense of. If we want to win the war of public opinion—and in a democracy that's really the only war that matters—we need to do better.