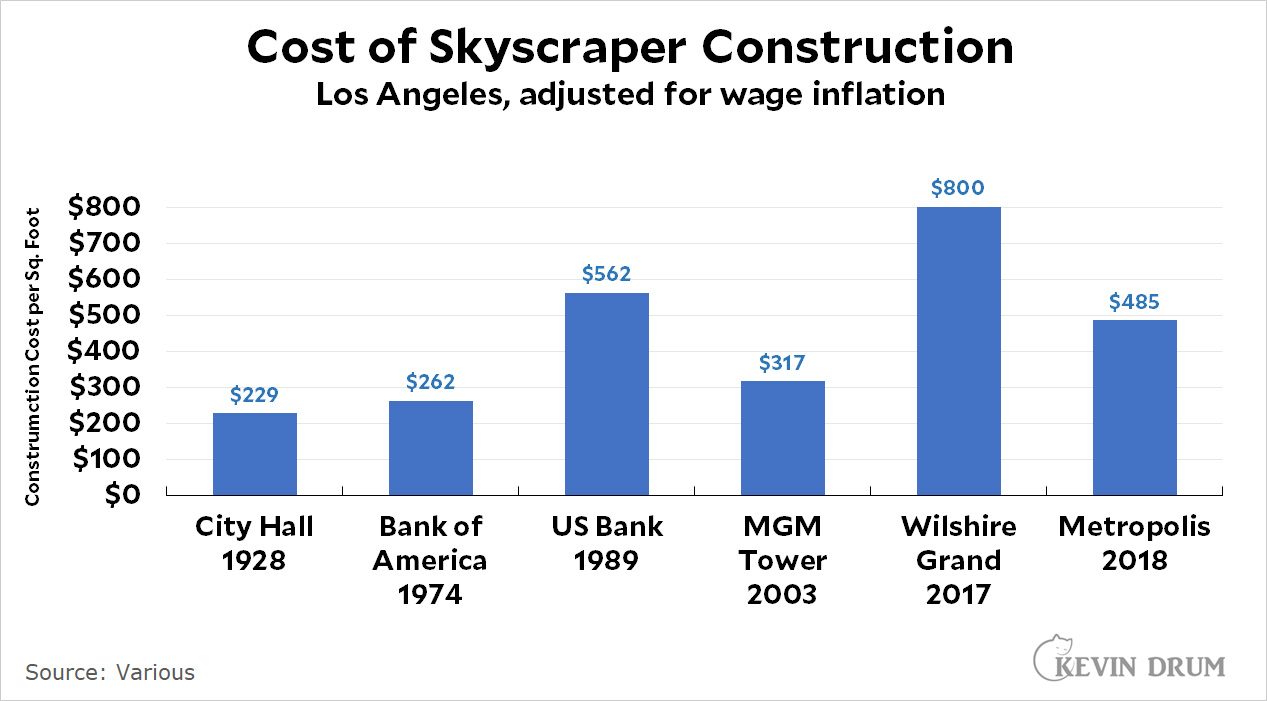

Why is it that we've seen no productivity gains in the construction field? For example, here's the cost per square foot of building a skyscraper in Los Angeles over the past century:¹

Construction costs vary depending on both the type of building and what's being counted. The cost of the Wilshire Grand, for example, includes the entire plaza. The tower alone cost less, but nobody ever seems to break down costs so you can do an apples-to-apples comparison.

Construction costs vary depending on both the type of building and what's being counted. The cost of the Wilshire Grand, for example, includes the entire plaza. The tower alone cost less, but nobody ever seems to break down costs so you can do an apples-to-apples comparison.

That said, there's clearly an upward trend, and it's probably safe to say that it costs more to build a building in LA than it did a century ago. Why? Shouldn't we expect that productivity gains over that period would make it cheaper to build?

Several people have lately taken a crack at this question, but is it really a mystery? Productivity gains come from automation, and the construction industry has barely automated anything in the past century. To build a house, you mark out a foundation, dump in some concrete, erect a frame, and then fill it up with stuff. All of this is done by people using hammers and wrenches and nailguns, the same as it's always been done.

Commercial construction is bigger, but not much different. You need cranes and elevators and miles of plumbing and electrical work. Pretty much all of it is done by hand, and there's no reason to think that manual labor like that should become more productive over time.

Beyond that, modern buildings are earthquake proof, flood proof, fire proof, and more efficient—all of which add to the cost of construction.

Is this ever going to change? "Automation in construction" is a thing, but even today it's still talked about in terms of what it "might" accomplish if anyone adopts it. For now, there's very little on the horizon and construction is just another victim of Baumol's disease.

¹Why Los Angeles? Because New York City is a world unto itself and isn't remotely representative of the US as a whole. LA was the next biggest city, so I chose it instead.

And in case you're wondering, the reason I didn't include any skyscrapers between City Hall and the Bank of America building is because there aren't any. Skyscrapers taller than City Hall weren't allowed until the early 60s, so the entire era from 1928 to about 1965 is a wasteland, skyscraper wise.