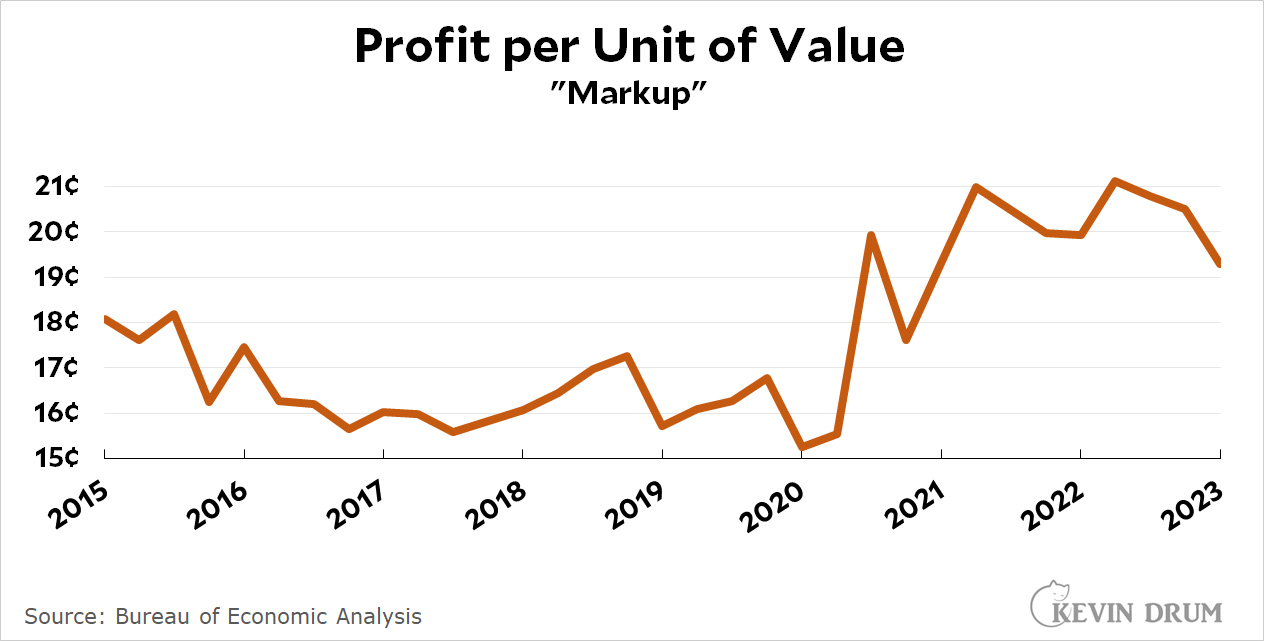

As we all know, corporations have raised prices substantially over the past couple of years, generating huge windfall profits. Is this "greedflation" the real cause of our recent bout of inflation?

In a nutshell, Eric Levitz says no. All that happened is that the pandemic caused supply shortages while government stimulus payments kept demand high, which caused prices to rise. Corporations then went along for the ride. I think this is broadly correct, but not entirely. After all, the evidence suggests corporations didn't just go along for the ride. They increased prices well beyond the rate of inflation. Was that related to lack of competition?

This raises an obvious problem: Corporate concentration has been transpiring over decades. In 2019, U.S. industries were roughly as concentrated as they were in 2022. Yet in the former year, inflation sat near 2 percent, a low level by historical standards. In the latter year, by contrast, prices rose by 6.5 percent. So why did corporate concentration yield historically low inflation throughout the 2010s, only to suddenly produce exceptionally high inflation following the pandemic?

Indeed. If they could get away with this, why wait for the pandemic?

It is unclear why corporations would feel compelled to wait for an “excuse” before seeking to maximize their profits....Generally speaking, companies do not feel compelled to provide an excuse for pursuing their mercenary interests....U.S. firms have been perfectly happy to offshore jobs to low-wage areas, even in the absence of an economic crisis that would serve to rationalize such profit-maximizing endeavors. Pharmaceutical firms, meanwhile, routinely price-gouged on life-saving medicines, even when inflation was near historic lows.

I think there's a straightforward answer to this question of timing. During periods of low inflation, price increases are conspicuous and consumers react to them. Big, flashy price increases run the risk of consumers abandoning your product and substituting something else.

But when the economy is chaotic and inflation is already high—and consumers are faced with endless news coverage of it—these constraints ease. If inflation is running at 8% and everyone is panicking, it's barely noticeable if a bag of Cheetos goes up 8% or 17%. It just seems like yet another wild price increase, like eggs or beef or used cars experienced for a while. At the same time, there's little risk of your prices being undercut, not because of corporate concentration but because everyone else is suffering supply shortages at the same time.

So my take is simple: Our current round of inflation is fundamentally a result of pandemic shocks, but it's been made a little worse by greedflation. This stands in stark contrast to the usual bogeyman of labor costs, which have been rising at less than the rate of inflation. In other words, it's not that greedflation isn't real—it is—it's just that it's a modest part of the whole story. That's how companies are able to get away with it, after all.