The Washington Post has a devastating but deadpan story today about the efforts of a private equity firm to buy up anesthesiology practices all over the country and then jack up prices for everyone. It starts in Denver:

The multibillion-dollar private equity firm Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe took less than a year to create, from scratch, Colorado’s biggest and most prominent anesthesiology practice.

The financiers created a company, U.S. Anesthesia Partners, which in 2015 bought the largest anesthesiology group in the Denver region. Then it bought the next largest. Then it bought a few more....The Federal Trade Commission, which is supposed to prevent unfair business practices, questioned the company’s growth but did not stop it.

The company raised prices for its services — one by nearly 30 percent in its first year in Colorado — and  continued raising them for several years, according to interviews and confidential company documents obtained by The Washington Post.

continued raising them for several years, according to interviews and confidential company documents obtained by The Washington Post.

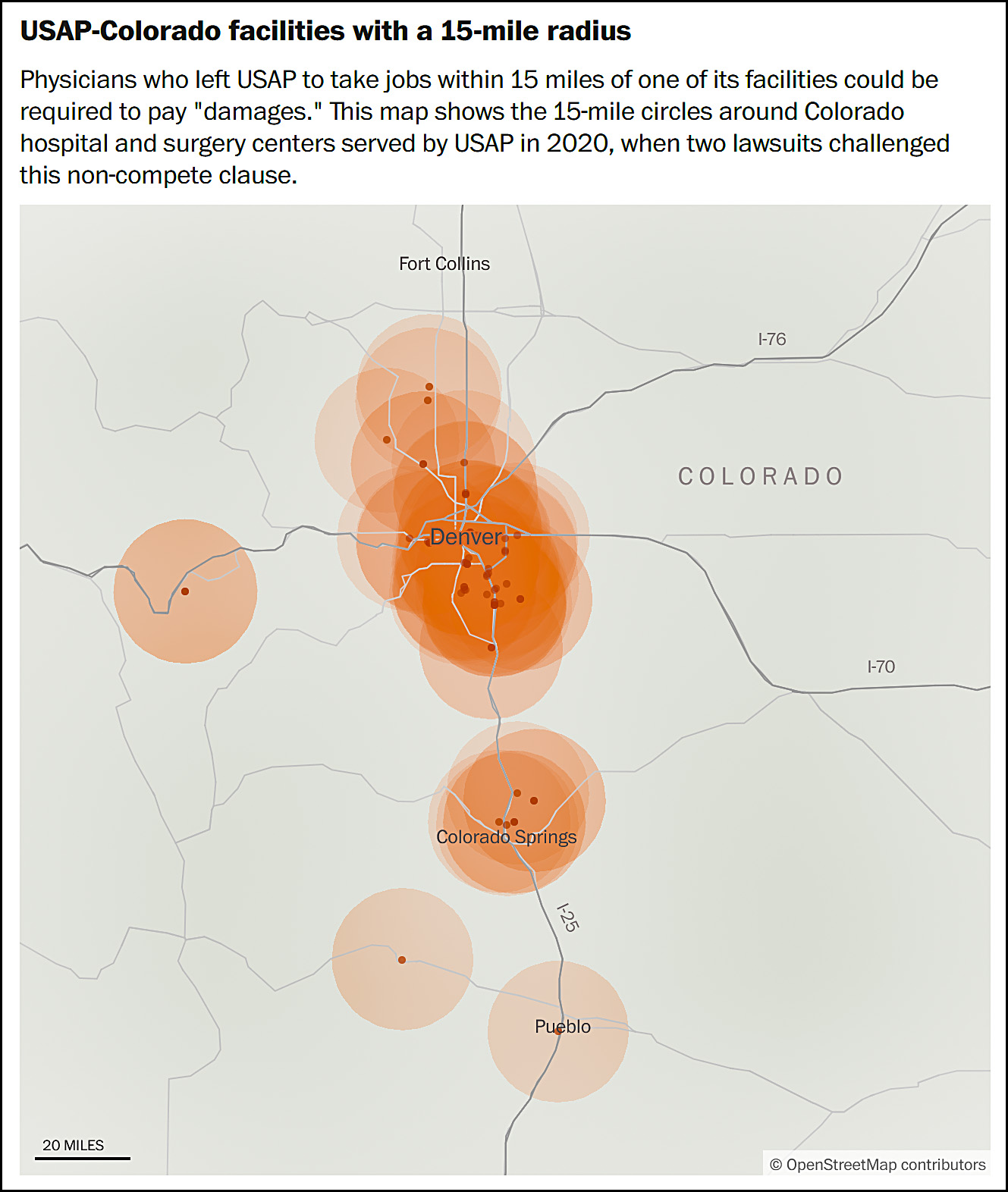

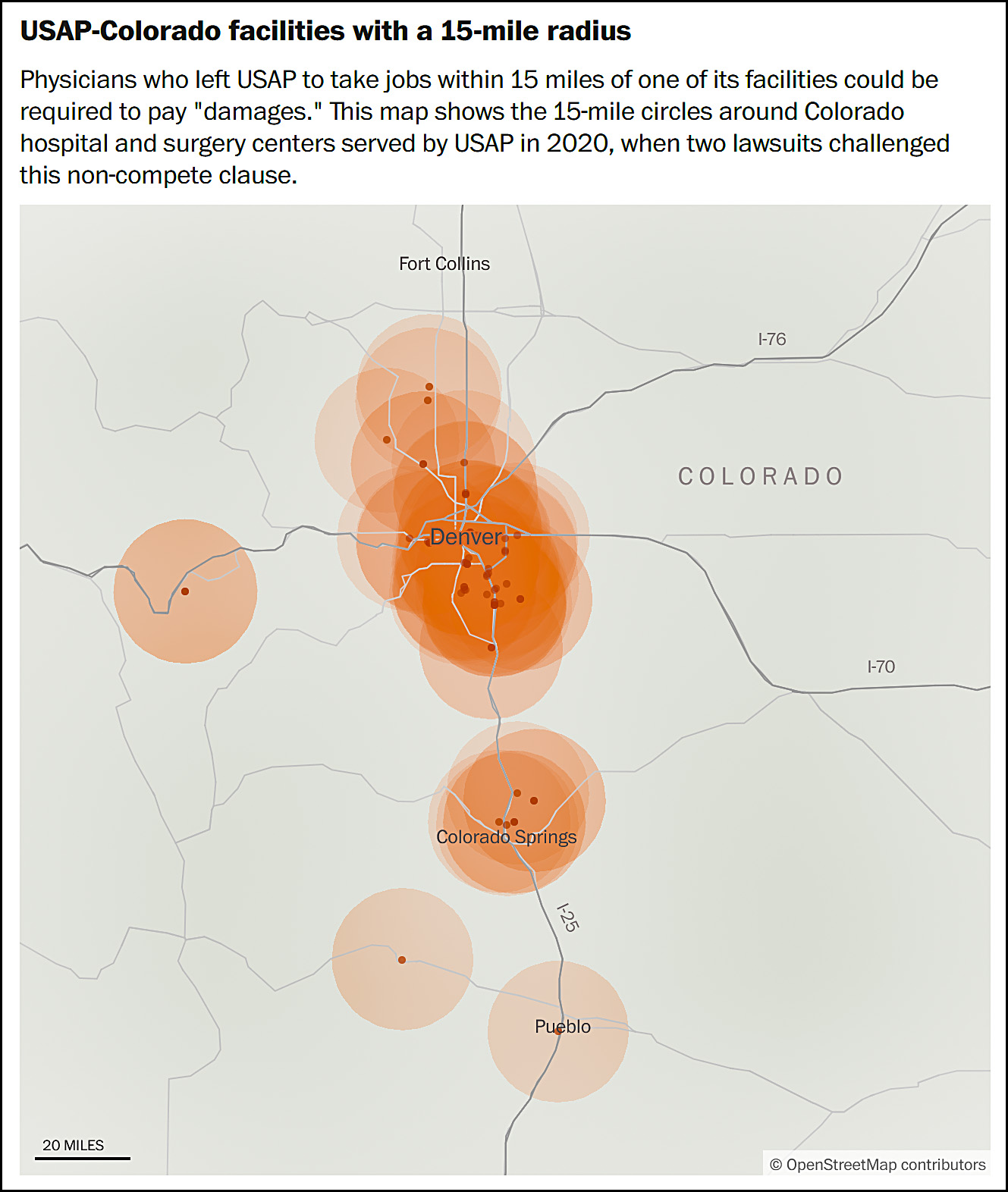

And it's not just Colorado. It's also Texas. And Florida. Indiana. Maryland. Nevada. Tennessee. Washington. But the Post story is based on leaked documents about the Denver practice, so that's what the story is about. In short, practices were acquired. Rates increased. Doctors were tied up with noncompete clauses. Then their pay was cut and hours skyrocketed. The FTC looked into things but shrugged and did nothing. And once the acquisition spree was complete, it was time for phase two:

With its acquisitions, USAP had become the region’s preeminent anesthesiology practice, and it quickly sought to raise rates, according to documents. One page of an internal USAP company presentation labeled “Guiding Strategies” at the time listed 11 points.

“Accelerate rate increases,” said one. “Pricing +/-5% range, for market’s lead insurers,” said another....For patients insured under the Cofinity network, effective payment to USAP jumped 29 percent, according to the internal company documents. For patients covered by another insurer, Anthem, USAP rates would rise 17.5 percent in the first year the contract was up for renewal, according to the documents.

.....Another doctor group in Denver, Guardian Anesthesia, was charging United, a major insurer, about $75 per unit in 2020; when USAP won the contract at the hospital where Guardian had been operating, it charged about $125 per unit, or 66 percent more for services provided by the same anesthesiologists, according to the documents.

How much does it matter if Microsoft purchases Activision? Maybe some games will become exclusive to Xbox. Maybe not. It's hardly the world's most pressing concern, but it's getting overwhelming attention from the government and in the media.

At the same time, the real action is under the radar, where de facto monopolies are constructed by private equity firms all the time. They're a tenth the size of the Microsoft deal, but their impact is actually far greater: not just a few gamers here and there, but, in this case, every single person who has a hospital procedure in one of ASAP's territories. Maybe it's in situations like these that the FTC ought to do more than just ask a few questions and then leave.