What really happened with Sweden and COVID-19? The story is a little more complicated than you usually hear, but you don't have to get too deep in the weeds to see that something interesting happened there.

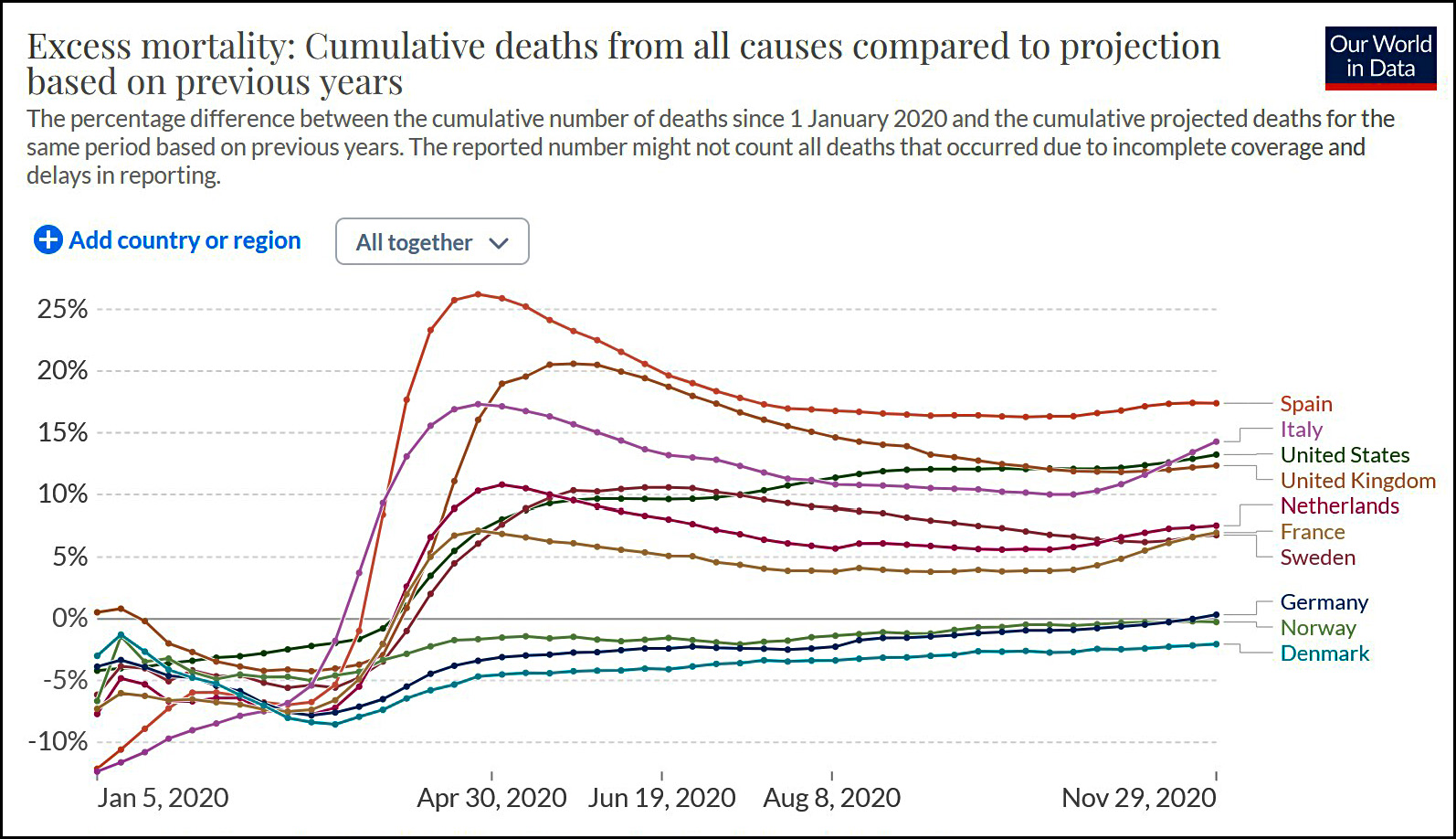

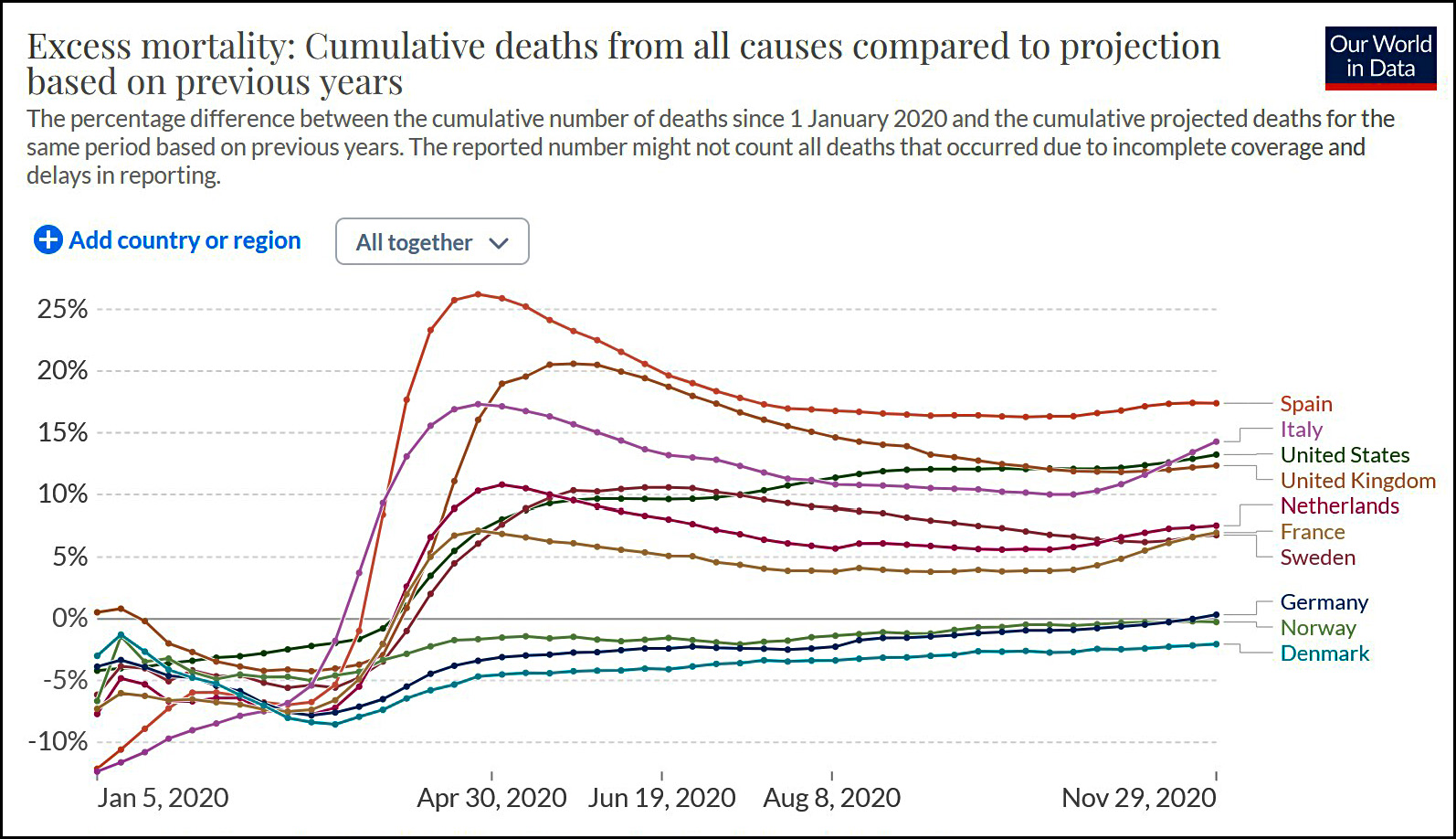

Start off in 2020, when the pandemic begins and Sweden adopts the most hands-off policy of any peer nation. There are no lockdowns, no school closings, no restaurant closings, and no masking. Here's how they did:

Even in those early days, Sweden's death toll was fairly low, and it would have been even lower if not for their catastrophically bad handling of nursing homes. If they had even matched the performance of other countries in their protection of the elderly, their excess mortality rate would have been down around 5%.

Even in those early days, Sweden's death toll was fairly low, and it would have been even lower if not for their catastrophically bad handling of nursing homes. If they had even matched the performance of other countries in their protection of the elderly, their excess mortality rate would have been down around 5%.

Still, the pandemic continued to rage and Sweden's death rate was higher than other Scandinavian countries. So in late 2020 they cracked down a bit. Large groups were prohibited, schools were allowed to close if they wanted, and the government gave itself authority to shut down shops.

Importantly, though, these changes were modest and mostly voluntary. In practice, almost nothing changed. Restaurants, bars, shops and gyms all stayed open, and although schools were allowed to close, few did.

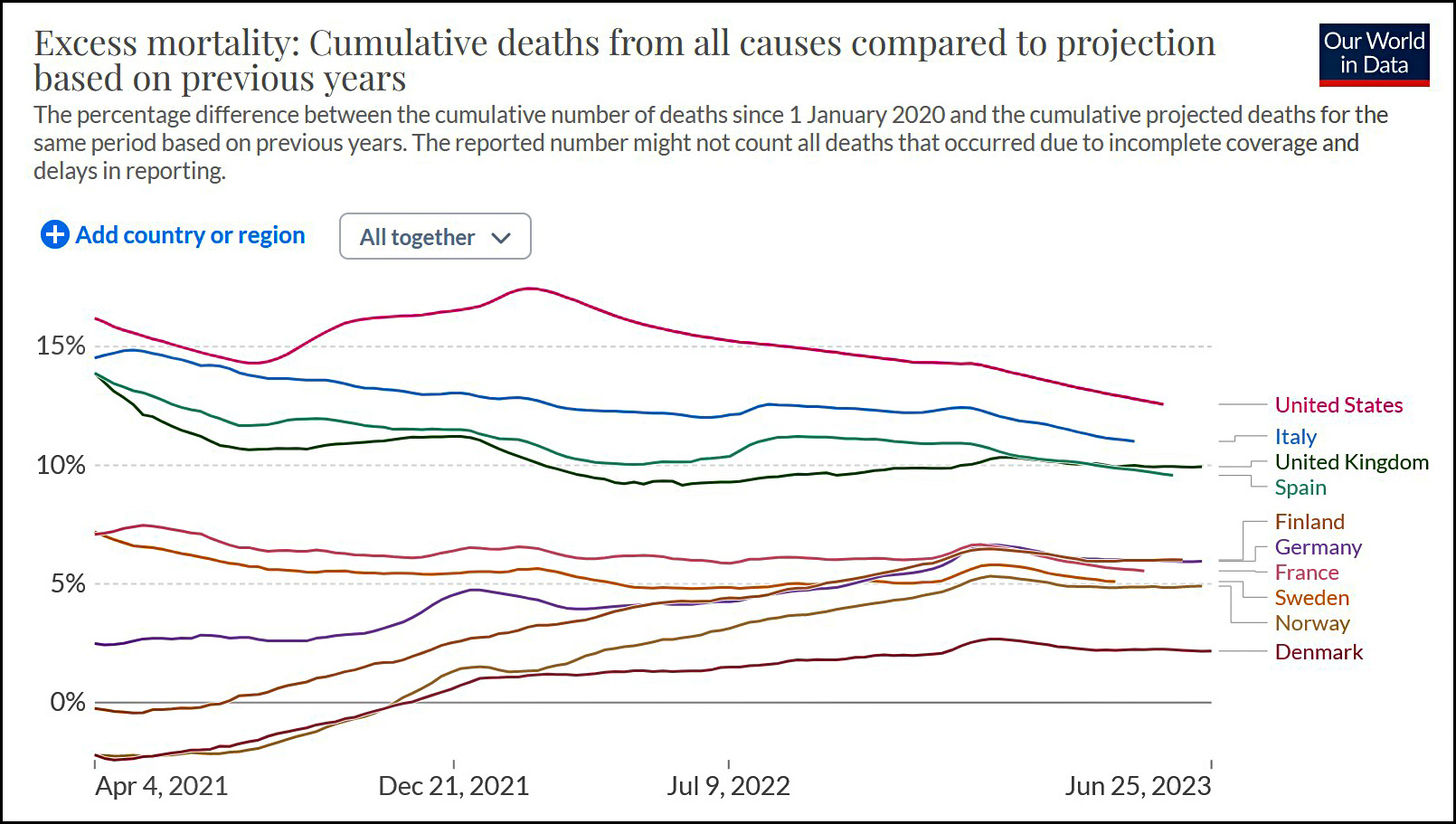

In one sense then, the "Swedish model" changed when the COVID death rate stubbornly stayed too high. But it was a very modest U-turn, and Sweden remained far more open than most other countries. Its model was basically intact, and it eventually produced this:

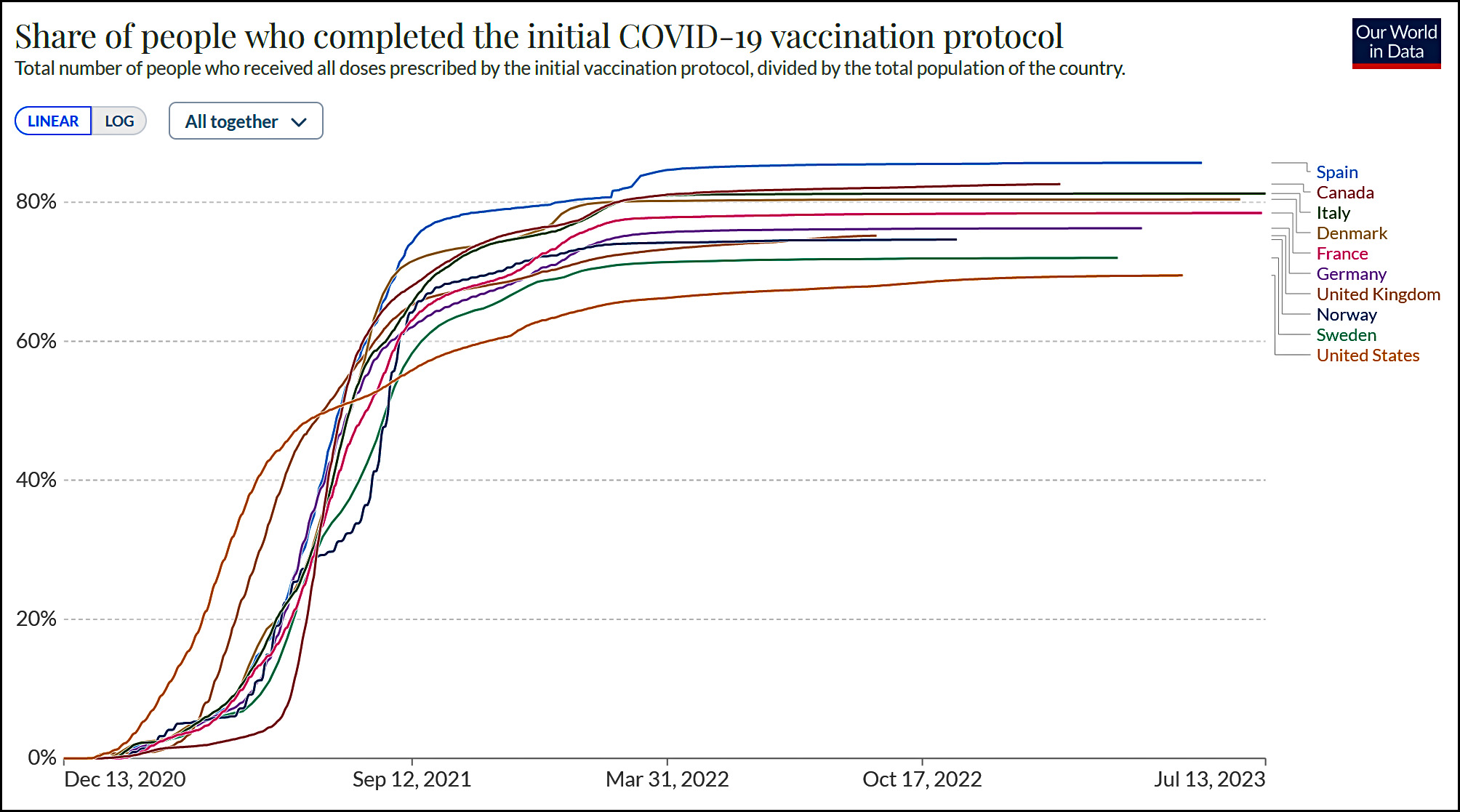

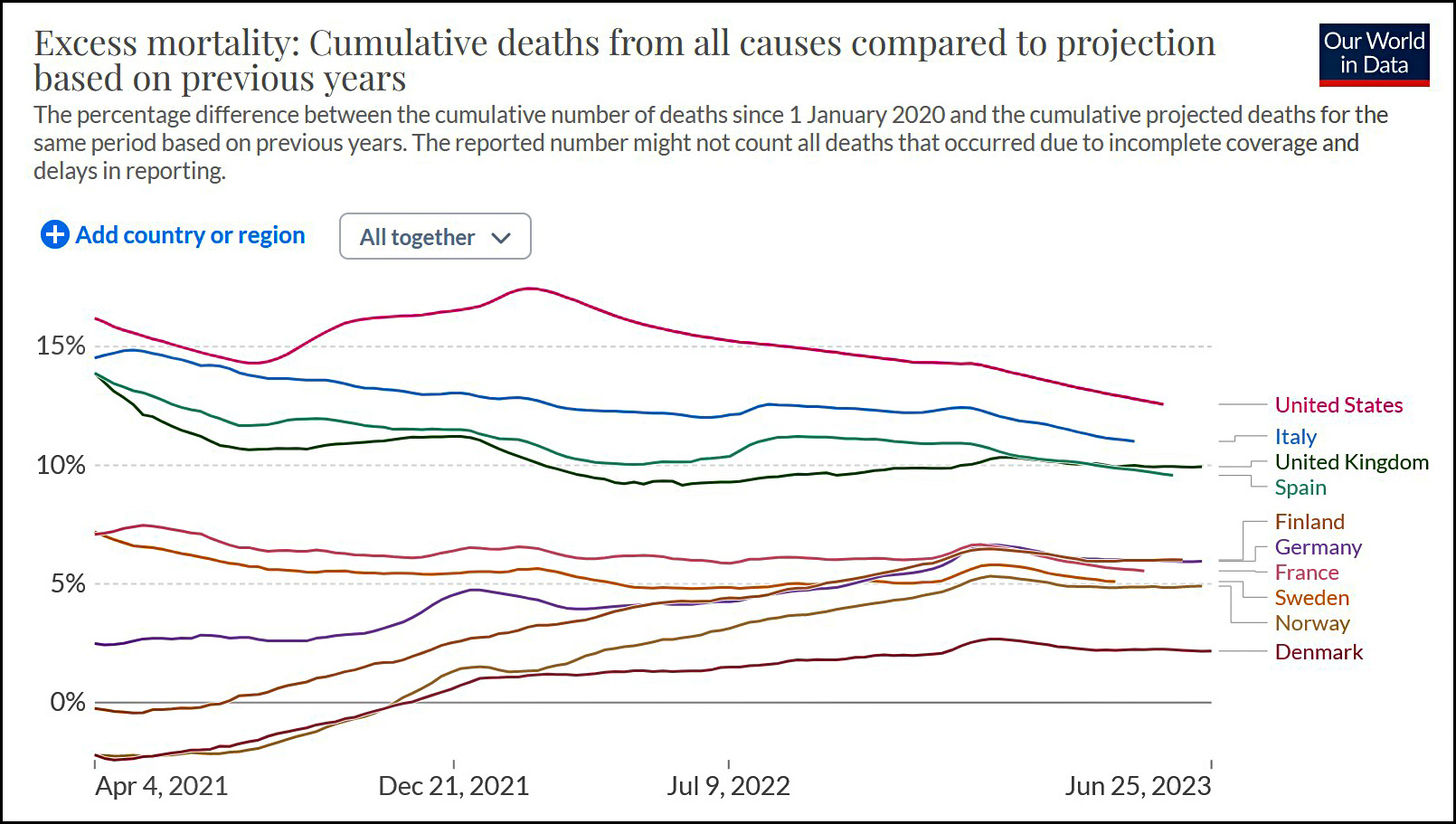

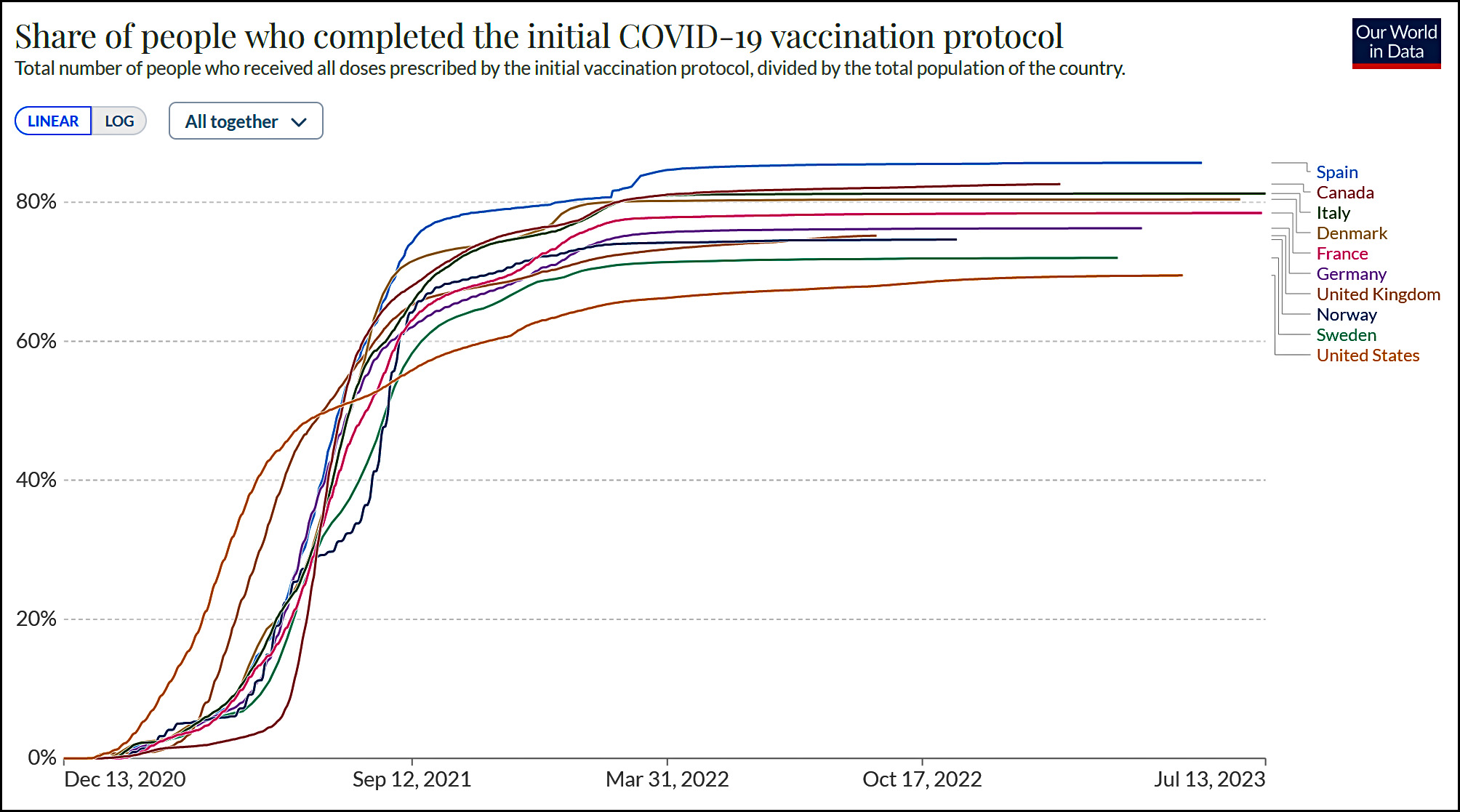

Over time, Sweden has had one of the best excess mortality rates among advanced countries despite having one of the worst vaccination rates:

Over time, Sweden has had one of the best excess mortality rates among advanced countries despite having one of the worst vaccination rates:

One reason for Sweden's success is that although government recommendations were just those—recommendations—Swedes generally took them seriously:

One reason for Sweden's success is that although government recommendations were just those—recommendations—Swedes generally took them seriously:

In a survey by Sweden’s Public Health Agency from the spring of 2020, more than 80% of Swedes reported they had adjusted their behaviour, for example by practising social distancing, avoiding crowds and public transport, and working from home. Aggregated mobile data confirmed that Swedes reduced their travel and mobility during the pandemic.

Swedes were not forced to take action against the spread of the virus, but they did so anyway. This voluntary approach might not have worked everywhere, but Sweden has a history of high trust in authorities, and people tend to comply with public health recommendations.

Would this work elsewhere? One may doubt. But it worked in Sweden and the results were manifold. Restaurants stayed open and people continued to eat in them. Businesses mostly stayed open and people continued to work. Schools stayed open and kids continued to learn. All this happened with fairly minimal intrusion into people's lives and no panic or constantly shifting guidance. There's a lesson to be learned here.

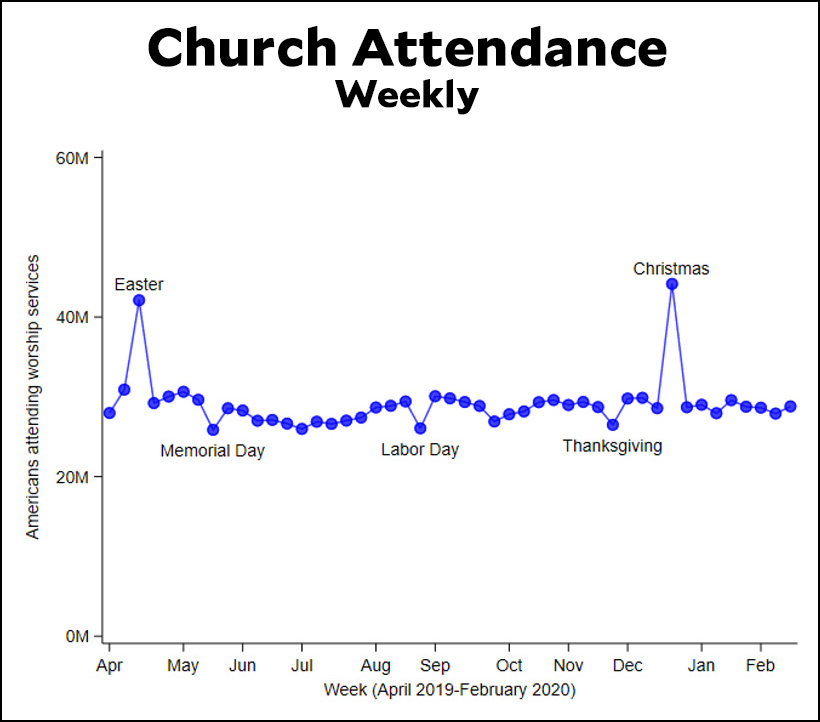

Week in and week out, there are roughly 25 million Americans at church each Sunday. Note that this is not the number who attend church every single week. It may be different people each week who make up the 25 million. So how does this compare to the number who say they attend church?

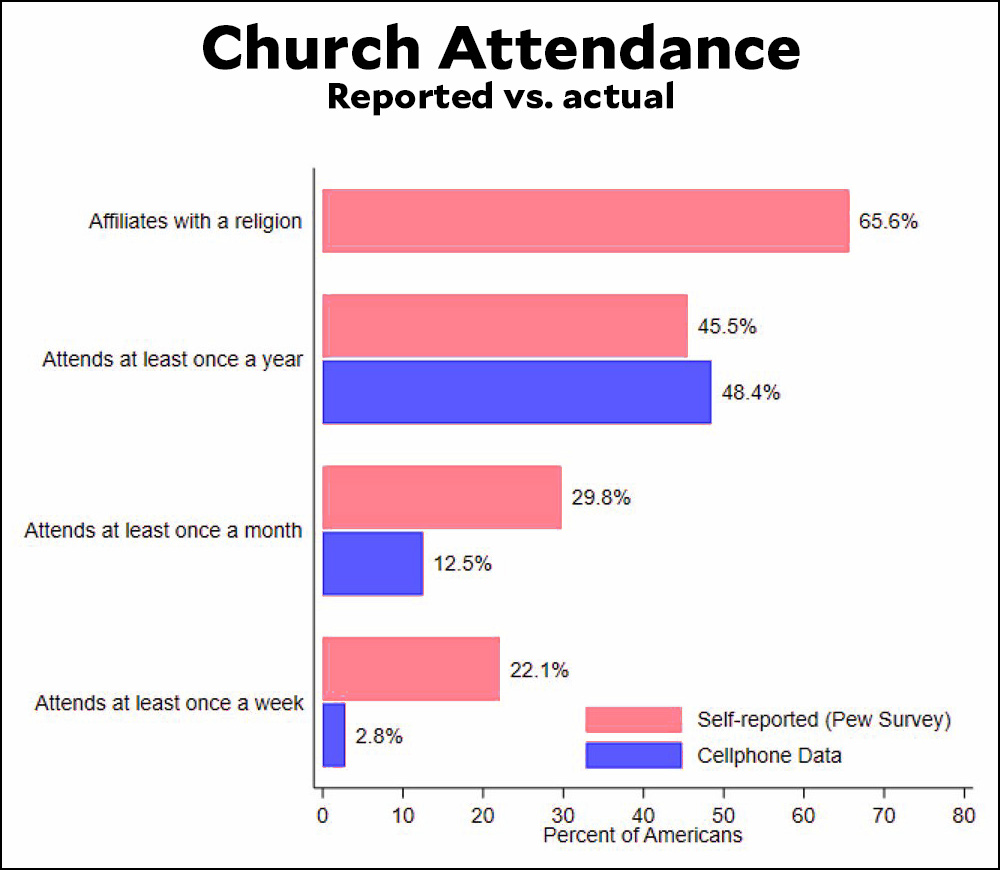

Week in and week out, there are roughly 25 million Americans at church each Sunday. Note that this is not the number who attend church every single week. It may be different people each week who make up the 25 million. So how does this compare to the number who say they attend church? People lie a lot about church attendance! A quarter of Americans say they attend church weekly, but in reality fewer than 3% of them do. That's about 8 million regular weekly churchgoers.

People lie a lot about church attendance! A quarter of Americans say they attend church weekly, but in reality fewer than 3% of them do. That's about 8 million regular weekly churchgoers.