[WARNING: This post is almost certainly wrong. Click here for an update showing how and why Mississippi test scores really did go up after 2013.]

I think I may have been wrong about something.

Over the weekend I wrote a couple of posts about Mississippi's "reading miracle." I looked things over and decided the evidence pointed toward genuine improvement following a 2013 reform that emphasized phonics instruction. Before the reforms Mississippi's white kids scored nine points below the national average on the NAEP test. By 2022 they were scoring five points higher. Black kids did about the same.

Not bad! But one of Bob Somerby's comments continued to niggle at me. Among other things, the 2013 law mandated that third-grade kids who failed a year-end reading test be held back a year. This affected about 9% of all third graders.

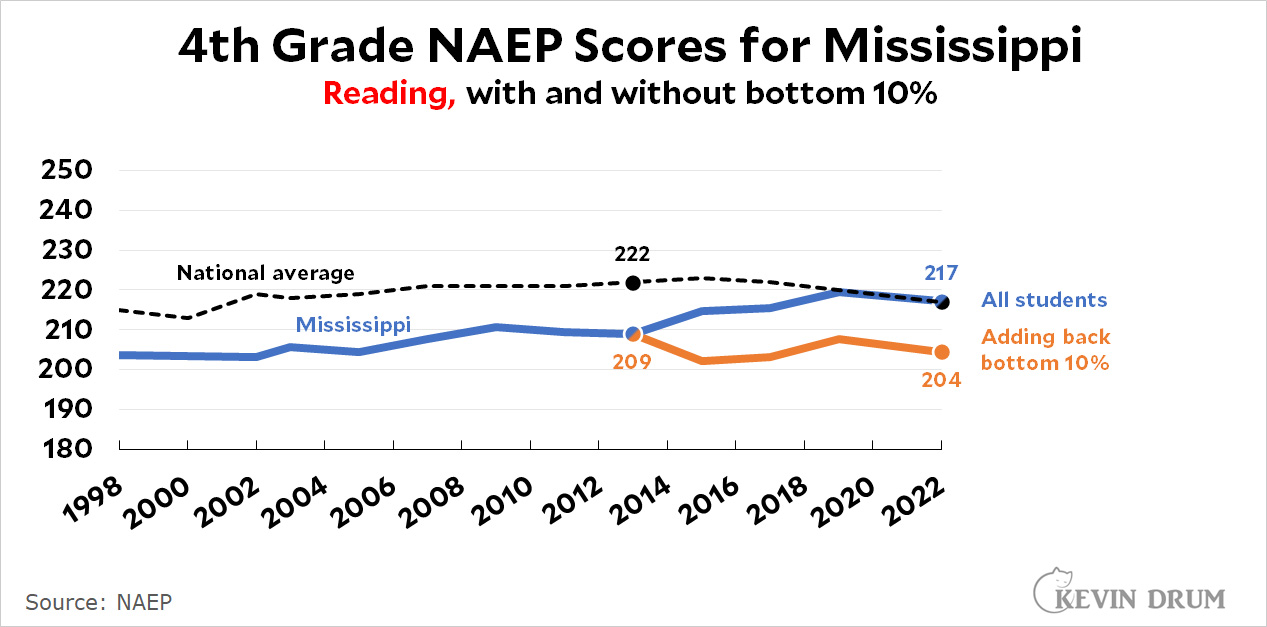

This means that if we then test in fourth grade we're automatically going to get higher scores than we should because the bottom kids are no longer in the testing pool. They're still back in third grade. I figured this effect would be small, but I figured wrong:

In 2013, Mississippi fourth graders are 13 points below the national average if you look at all students. After that year, "all students" excludes all the bottom kids who were held back. What we need to know is what the Mississippi scores would look like if we added them back in.

In 2013, Mississippi fourth graders are 13 points below the national average if you look at all students. After that year, "all students" excludes all the bottom kids who were held back. What we need to know is what the Mississippi scores would look like if we added them back in.

By chance, this turns out to be fairly easy to estimate, so I did that. It's the orange line. Follow it along and it turns out that Mississippi scores in 2022 are still about 13 points below the national average. In other words, the 2013 reforms had all but no effect.

Easy come, easy go.

Pingback: How miraculous is Mississippi? – Kevin Drum

So it goes.

It being Mississippi and all, I wonder if they decided they'd hold back the low-scoring 3rd graders knowing that the NAEP testing concerns 4th graders (does NAEP test other grades?).

Reading and math for 4th graders; reading, math, and history/civics for 8th graders (the exact subject breakdown changes from year to year). A smaller sample of 12th graders is assessed on the above topics as well as science (including some hands-on chemistry).

Any given student is assessed in only on subject. So, for example, Sally gets math OR reading, but not both.

You're asking the wrong question. For those kids who are held back, does it help them in the long run?

This effect you've calculated is only temporary. It's not like the same 9% are going to be held back forever; the next year they'll advance to 4th grade. If, at that time, they're better-prepared for fourth grade, it means a real improvement for the average scores of 4th graders. If that improvement carries through to later grades, it's still a real improvement. But there are important IFs there.

I'll repeat my question from an earlier post on the same topic: What's so terrible about holding kids back a grade if they haven't mastered the necessary skills to advance to the next one?

Social stigma? Perhaps advancing a kid who is struggling with a subject is better off advancing in grade but getting specific extra instruction on a particular subject.

That might be the case. But in practice, what actually happens is that failing kids are advanced but for some reason -- I can't think of any good ones, but surely they must exist 😉 -- never receive that extra specific instruction.

The rhetoric of professional educators tends to speak of keeping children with their "peer group". The problem is that when they say "peer group" they actually mean "age group" and the two terms are simply not synonymous.

I am afraid that you are very much correct on that one. "That's what I like about high school girls: I get older, they stay the same age."

It's not clear that holding kids back helps them much, if at all, and it would be counterproductive to have a kid repeat an entire grade just because they were substandard in one important skill. Rather than holding kids back, it's better to offer supplemental school-year instruction and/or summer school in order to get them up to, or close to, grade level in their weak subject.

It's certainly stigmatizing to be the "dumb kid" in class, but that isn't always apparent. It's even more stigmatizing to be the kid who was held back, especially at lower grade levels, and it's not clear that there's much pedagogical benefit.

In this case, it's hard to imagine that Mississippi intervening at the grade immediately below the testing grade is any sort of coincidence. It is almost as hard to imagine that this was done to benefit the students. In fact, you could probably come up with a half dozen more effective approaches, but they might cost more money than holding a kid back. In fact, if the kid ends up dropping out at age 17, the state would probably regard that as a net benefit.

The main question posed by Somerby and Kevin is whether a specific teaching technique, namely phonics, is causing the improvement. The kids who are held back get up to an additional year of instruction and they are older (some kids just develop more slowly than others) so of course they do better, whatever the technique. This is not miraculous. So the improvement can't be automatically ascribed to phonics. To test whether the specific technique is responsible you would have to have two groups who are treated the same except for the teaching technique.

Some people writing about this, for example Somerby and Kevin (and some others who pointed out the problems with the Mississippi results) have some comprehension of how variables need to be isolated. Others in the media including Kristof apparently do not.

"The main question posed by Somerby and Kevin is whether a specific teaching technique, namely phonics, is causing the improvement."

For what it's worth, I've never posed that as the main question, or tried to make any such assessment at all.

I agree with your basic idea, namely that most kids will do better after five vears of graded instruction than they would have done after four. For me, the main question is how much that extra year of instruction for Mississippi's lower performers improves their performance on the Naep, and with it Mississippi's average score.

Holding them back may be a good idea (or not). I'm merely asking how much this procedure inflates Mississippi's average Grade 4 scores, as it almost surely does.

Holding kids back need not inflate NAEP scores. If a child is 4 years below the white mean, is held back and is then 2 years below, including him isn’t going to raise the black mean much if the black mean is 2 years below the white mean. Adding a score that is at the mean does not change the mean. At your blog, mh posted data showing that with retention the average age goes up but not the mean — it decreases slightly.

Kevin’s adjustment is incorrect because the retention policy started in 2002, whereas the special instruction was phased in gradually after 2013. All he needs to do is remove his adjustment entirely, then compare 2002-2012 with 2013-2023 to see the effect of retention with and without special instruction.

You really should read your comments section.

Over time, holding third graders back will almost surely inflate the Grade 4 mean.

Presumably, the kids who get held back will score higher when they finally take the Grade 4 tests after 5 years of graded instruction, as compared to how they would have scored if they had taken the Grade 4 tests "on time."

Presumably, they'll score better after the extra year of instruction. That is the obvious rationale for having them repeat 3rd grade in the first place.

That doesn't mean that the retention policy is bad. (That remains a matter of judgment.) It simply means that it complicates statistical comparisons between states which do and don't hold a lot of 3rd graders back.

This isn't especially complicated. I'm puzzled by your semi-obsession about this.

You really think readers here are fools, seriously, removing 9% of the worst performers does not need affect the data? (And this whole age thing does not detract from the fact that means of analyzing the data was altered by removing the worst performers). And then you state is better not to have any adjustments? To make a valid comparison, the data base sets need to be the same, apples to apples so to speak. If every state of the union did the same their scores would also go up. It appears to me that Mississippi is committing this giant fraud and sadly it is the students who feel the brunt of the fraud. Would you at least admit that Mississippi is testing a different set (type) of student? Or are you saying Mississippi was flunking 9% of the third graders in 2002?

Try it with a group of numbers you invent. I don't have time to teach you stats. Remember that the numbers from which the 9% are being removed are not the same children as the group that 9% is added back into. Why? Because that is how the program worked in real life.

You seem very confused about the timeline involved.

There was no program in 2002 but kids were being held back at very high numbers compared to other states. In 2015 they passed some legislation to improve reading instruction. It probably took a year or two to get that program going in enough schools to make a difference. That means improvement would be gradual. In 2022, significant improvement showed up on the NAEP (probably due to covid too). Because covid disrupted both education and testing, this is the first clear sign of improvement in 4th grade reading. The results are NOT a fraud. Look at the links I posted below about the impact of retention on NAEP scores. Drum's approach is not a good way to test Somerby's idea that retention accounted for the gains. You can just compare 2002 to 2022 and see the change. There was retention all along, at different rates and not always 9%, but there is also a technical explanation below (scroll down in comments) explaining why the retention cannot be the explanation (aside from the fact that MS has always had some level of retention before beefing up their reading instruction).

You don't want to start calling things a fraud until you've eliminated more benign explanations. It is like being in a poken game, dropping one of your cards on the floor, and then accusing all around you of cheating.

If Mississippi is gaming the system then yes I would consider that a fraud. Your regressive analysis about the age of the test takers does not alter the fact that the removal of the worst test takers will alter the data. That’s not statistics that’s arithmetics -addition and division. Since you don’t have a number for 2002 retentions, I’m not sure why you even brought it up. Like BS said, increasing retention may well be a good policy, and based on the average age of test takers that you brought up, it may well be something that needs further evaluation. But, all of this does not alter the fact that the data sourcing is originating from a different set and thus not a valid comparison. Now as to KD’s graph, I would like to see how he created the adjustments.

That is incorrect. "Adding a score that is at the mean" will change the mean if you SIMULTANEOUSLY remove another score from below the mean.

If I have four hens that weight 6 pounds each and one that weighs 4.5 lbs, the mean weight is 5.7 lbs. If I remove the skinny hen, fatten it up to 5.7 lbs (the prior mean), and add it to the next group I weigh, while also removing that group's skinny hen, the average weight rises to 5.9 lbs.

You don't even need statistics to understand that replacing a low score with a slightly higher score will raise the average.

This was my thought exactly. Kevin might have started out mainly interested in whether "the science of reading" leads to miraculous improvements in test scores. But the key point, to me, is that requiring students to meet educational targets to advance to the next grade results in a lot more students meeting targets. There's probably room for argument whether the increase is due to more parental focus, to students' desire to avoid the stigma of being "left back", to the effectiveness of summer school in helping lagging students catch up, or just to giving lagging students an extra year to acquire the skills (or maybe some other cause that doesn't spring readily to mind).

There's been a lot of ink (and a lot of pixels) spilled over students who graduate from high school lacking basic skills. Connecticut educators are on record as opposing having any child repeat a grade or be denied a diploma for any reason; I expect this attitude is pretty standard in the country. It doesn't help the students, unless the only objective of the educational system is to avoid denting students' self esteem.

I -- very, very reluctantly -- agree with you.

As a teacher who used to follow data closely, I've always been baffled as to why we compare states based on grade levels rather than age or years of schooling. Holding students back is such an obvious way of gaming the comparisons.

Similarly we act as if it is impossible -- IMPOSSIBLE -- to compare schools/districts/states based on profiles of actual household income per family (median, mean, etc) rather than just free/reduced lunch or other income cutoffs.

I do very much appreciate your habit of looking at high school test scores. There is very good reason (based on this basic data) that practices optimized for early reading scores don't hold up over time -- and critics of phonics instruction would predict exactly that -- a short term boost but not much long term gain.

Ok, so if you factor the flunked 3rd graders back in, it doesn't look so impressive. But does it matter? Isn't the whole point that they're held back and allowed to catch up until they're ready to move on? What am I missing?

Fox News was gushing yesterday about how Mississippi's "conservative" approach to teaching reading had produced the best scores in the country. Which was blatant bullshit. Mississippi's scores fell slightly less than some other states, and they have made some modest progress over the years, but that's not too hard to do when you've started from rock bottom. Mississippi has been a red shithole for decades -- how come that wasn't the result of "conservative" education policies?

That's the question I keep asking. I mean, 'holding a kid back' is _exactly_ the equivalent of 'giving a kid a year's worth of extra instruction'. Quite frankly, I've long since despaired of most districts doing the right thing by their students and, you know, actually providing the actual funding and manpower that a sincere effort to improve outcomes entails.

It matters if you are trying to identify best practices and methods to improve learning.

Identifying an improved teaching method that improves student comprehension by nearly a grade level is a very different discovery than figuring out that failing a large number of kids in the third grade will boost 4th grade scores but have little impact by the 8th grade (other than those kids being a year behind their peers).

Given the lack of improvement in later years, its not clear that failing the kids in 3rd grade works very well at all.

The eighth graders are not the same as those tested in 4th grade. The 8th graders may not have been part of the improved reading instruction, given that it was phased in across different schools. To see whether the learning fades, you need to compare the current 4th grade scores against the 8th grade scores obtained in 4 years from now.

Obviously you can lag the data 4 years and see that this is not happening. The improvement shown in 4th grade test scores fades when they are tested in 8th grade.

But here's the kicker....

Elsewhere you are arguing that there was no retention change in 2013 and no need to lag the data. Here you flip your argument on its head. Flip, flop, flip, flop...whatver logic is needed in the moment.

You dont seem to be discussing this in good faith.

I didn't say that. The retention change seems to be in 2015. I said there was retention before that from 2002 onward. It is not at the same rate, even though Kevin seems to have used a constant rate.

The kids tested in 8th grade were in 3rd & 4th grade before the new literacy program was implemented. We won't know the effects for the first cohort of kids until 2026. I don't know what you mean by "lag the data" but this is a new program and one cannot tell whether it is working by examining 8th graders who were never exposed to it.

I get it that it is frustrating to misunderstand something complicated, but don't blame me.

That's not the way I read Kevin's graphs (from his original post) at all. Taking 2013 as the base year, scores for 4th graders had improved (relative to national averages) by about 6 points by 2017. Following these same kids to 8th grade, we see about 6 points improvement for 8th graders by 2023. Admittedly, most of this improvement seems to have come by 2015, so it's not obvious that practices in 3rd grade were decisive.

One of the tried-and-true methods of teaching is that 'repetition works'. I know this is true on the math side and have no reason to disbelieve it isn't true for the reading component as well.

This does suggest that holding students back is a useful intervention. I would love to see whether it impacts high school completion as well, because I can imagine it going two different directions: establishing reading skills in elementary school could help more kids graduate, or turning 18 while still a Junior in high school could prompt more dropouts.

Shifting to heavy phonics was never going to solve all problems with reading. I think direct phonics instruction is really useful, and I'm glad my kids got it. But decoding text is only one skill you need to read successfully in later grades. If you have a limited spoken vocabulary and little content knowledge, you are going to struggle mightily with comprehension.

On a different note, I just want to say that holding back 9% of kids is a HUGE percentage. I live in a state where that is almost never done, and when it does happen, it's usually with a Kindergartner (really little kids are less likely to be teased for it). In fact, I think most kids in my district that are held back are sent to a new school, so that the other students don't know it happened.

THIS You need a lot of nouns (and verbs, adverbs, adjectives, yes, I already know that) to be a succuessful reader. Kids from a language-impoverished background don't have that. But it's certainly possible for them to pick up on those nouns from their classmates on their first time through third grade and apply them on the next.

New language learners (such as immigrants or those who speak a non-English language at home) have their own needs that should be assessed. They are not included in the NAEP test.

Oh, I agree and know. But I wasn't speaking to that issue. When I say 'language impoverished', I mean exactly that: parents who don't interact much with their children, or the children of parents who not well served by the educational system itself. Kids with maybe half the vocabulary of someone who was actively engaged by their parents, parents with high expectations for their kids.

To put it more starkly, kids coming from families where Dad only interacts with his children to discipline them and Mom doesn't do anything much more than making sure their basic needs are met because she's on the sauce by no later than 11 am.

Kevin, you have added the 9% back in twice, not once, because the retention policy actually started in 2002 not 2013. The new reading instruction started in 2013 but retention was going on already. If you reverse the 9% you added twice (because it was already there in the data for 2002-2012), the curve looks impressive again.

To see the impact of retention without the improved instruction, compare the segment from 2002 to 2012 with the one from 2013-2023.

Better yet, don’t apply any adjustment.

Where did you find the historical yearly rates for 3rd grade retention in MS?

I only found one source for 2009 rates, showing MS had a 1% retention/failure rate for 3rd graders.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3688838/

I see your message being stated as fact in many places, but nobody provides numbers or data or links.

Mostly from these two sources:

"Here is an article that mh posted back when this discussion first started. To date, Somerby and Drum give no evidence of having read it:

"This article, in which the score gains were attributed to the third grade retention policy, was published in 2019:

“Mississippi rising? A partial explanation for its NAEP improvement is that it holds students back”

https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/mississippi-rising-partial-explanation-its-naep-improvement-it-holds-students

However, the author updated his article almost 2 years later.

‘Author’s Update, August 5, 2022: Analysis of NAEP demographic data shows that retaining students was in fact not a major contributor to Mississippi’s improved fourth grade NAEP results in the last few years—at least not the way this article suggested. The average age of Mississippi’s fourth grade test-takers was almost identical in 2002 and 2017; increased retention should have raised the age. That suggests that Mississippi has long had a higher retention rate than most states, perhaps making its reading retention policy less controversial than in other places. For further thoughts on how the retention policy has impacted Mississippi’s NAEP results, see my related Fordham Institute post from January 2022: “Student retention and third-grade reading: It’s about the adults.”’

The author asks you to review his newer article"

mh also posted these stats:

"The second piece of information comes from the naep itself. You can add student age in as a factor. Here’s what happens when you do that:

Grade 4 reading, 2022:

National public, below modal age, 232

National public, at modal age, 216

National public above modal age, 216

Mississippi, below modal age, XXX (no data: Reporting standards not met.)

Mississippi, at modal age, 223

Mississippi, above modal age, 212

The older students, presumably the ones held back, (above modal age), performed less well than those at the modal age."

Also, are you aware that MS schools have only been desegregated since 1971 and still have 32 schools that are under a federal desegregation order. How might that affect the scores of black NAEP test takers?

Note that these various sources estimate a higher % of retention in MS not lower, and that it is extraordinarily difficult to figure out the age of a student given their grade. Some are held back in 1st grade, some do not start promptly. Parents believe that their boys will do better socially if they are older, and some want their boys to be bigger physically to help in athletics. The coupling of age in grade is also disrupted when kids change schools. That makes Kevin's use of 9% even more arbitrary.

Your own source has data for 2002-2003 for MS.

"Literacy-Based Promotion Act

The Literacy-Based Promotion Act, also known as the “Third Grade Gate,” was passed by lawmakers during the 2013

Legislative Session. This law requires screening of all K-3

rd grade students to identify reading deficiencies and requires

that districts provide intensive reading instruction for those students who have deficiencies. It also requires the

retention of any student who does not meet the cut score on a summative reading assessment at the end of third

grade, unless the student has already been retained, is an English Language Learner who has received less than two

years of instruction in English, or has disabilities that exempt the student from the statewide assessment program.

Mississippi’s law omits important exemptions included in similar laws in other states with successful programs, and

the cut score required for passage of the test was raised significantly in 2019. Students who do not pass the reading

test the first time have two additional opportunities to take and pass it.

The Legislature has invested $15-million annually in reading coaches to improve literacy instruction in low performing

schools and in statewide literacy training for teachers in kindergarten through grade three, both of which have been

instrumental in improving reading scores. Additional funding is needed to provide literacy coaches in all schools."

Children who do not attend good preschools are unlikely to meet the criteria for advancing from kindergarten and less likely to pass the 3rd grade reading test.

"Mississippi assesses kindergarten students at the beginning of the year to evaluate their mastery of the early literacy

skills that are the foundation of success in kindergarten and beyond. Almost two-thirds of students entering

kindergarten in fall 2022 scored below the kindergarten readiness benchmark. On average, students who attended

public or private pre-k score above the 530 benchmark. Research indicates that 85% of students scoring 530 or

higher at the beginning of kindergarten are proficient in reading at the end of grade 3. (Mississippi Department of

Education)"

This Act was passed in 2015. That is too late to have benefitted the children taking the NAEP in the 8th grade. That means it cannot be that any effect has faded (Somerby's word, he also has said died).

Trying to use retention estimates to explain away the progress observed on the most recent NAEP is ridiculous in my opinion. Kevin's estimates have too many problems to be close to real. This has become an exercise in Somerby trying to explain away progress. I don't know why that is important to him, but his suggested explanations seem to work in the opposite direction, against his hypotheses, and Drum's analysis is meaningless, in my opinion.

I don't necessarily agree with everything you say, but I will commend you for promptly backing up your assertions with cites and sources.

Unlike some others who post here but whose names I won't mention.

For the record, I read it back in May, after the AP report appeared.

Unless there is a growing cadre of perpetual third graders, "adding back" isn't necessary because they are already included -- just in the next year's group of fourth graders. Holding kids back because they cannot meet standards is great as it gives kids a chance to succeed rather than fall further behind. This data would seem to indicate that it works, unless there is a growing number of kids that were held back multiple years.

Investing a full year to get higher test scores in 4th grade only to see those gains erases by 8th grade is an odd definition of success. What are we trying to achieve exactly?

It kind of goes without saying that adding an extra year or study will improve test scores....but how is this repeatable? Extend public school to 13th grade to ensure everyone is a year smarter at 19 than they were at 18? Are we all better off because of this?

Maybe....at minimum we should be talking about the merits of the actual cause of improving test scores for a few years before the effect fades instead of pretending that we have discovered a new teaching method.

Uh, I don't see anybody here saying that we've discovered a new teaching method; care to name some names?

Here is what they did. They discovered that their schools had poorly or entirely untrained teachers in reading instruction. They mandated at least 2-1/2 courses in reading instruction in teacher colleges and they made a strong effort to train those teachers already working in the schools. They bought and implemented a phonics-based reading program and mandated its use. They discovered that they had very few reading specialists (education experts trained in teaching reading to people with disabilities or problems learning). Many schools had none, so they allocated funds to train such specialists and assiged them so that every school had such a specialist to assist the classroom teachers and work with those students having severe difficulties. The testing at 3rd grade was to ensure that no child fell through the cracks without learning to read. The children identified were assigned to reading specialists who helped them improve sufficiently to pass the "gate" test at the end of 3rd grade. So, the extra year in 3rd grade was not just more of the same, but involved doing something different to help struggling kids learn. This was very successful in getting nearly every child up to the passing level. What is different about this program is that it was coordinated and funded and aimed at the entire study body of 3rd graders (and the K-2 classrooms as well, where early literacy starts). It took an act of their legislature and the will to do better. There was no doubt resistance.

Given this strong effort, why shouldn't the kids improve their reading?

Is this a "new teaching method?" Who cares? And does it make sense to argue about the degree of improvement (among which kids)? I don't think so. Kids need to learn to read and MS is helping them do that.

Is this a "new teaching method?" Who cares?

And that last is really the important bit. Who cares? What are we trying to do here? Help kids or assign culpability?

You are making an unproven assumption that the learning does not last, that it is erased. We don't know that because today's 8th graders didn't have their intensive literacy training. How then could they have forgotten it?

If you were examining scores for the 8th grade NAEP, there would be no reason to add back in the bottom 10% because there was not a retention program after 3rd grade. However, there is one afrer Kindergarten. Who would get held back? Those kids who didn't have the advantage of going to a good preschool. That makes them already behind before they have much exposure to a phonics-based reading program.

Somerby thinks the kids lose their reading ability after 4th grade, because the numbers are lower for those kids on this current NAEP. The kids being tested did not experience the program to improve literacy, because they were too old and it was aimed at K-3rd grade and not even implemented when they were in those grades. There is no reason to expect much beyond normal improvement for them. That doesn't mean they are losing their reading skills.

I suppose that if children are taught using a rote-phonics based program, they might forget what they learned over summer, but if they have learned to read fluently, they should be practicing their skills using books, even during the summer. The point of literacy training is to make kids able to read whatever they want, as they move through the upper grades. So, this idea that the 8th graders somehow lost their skills strikes me as a gratuitous smear.

The kids who will have experienced the new program will be taking the NAEP in 8th grade in 4 years, in 2026. The 2022 8th grade results are not informative, no matter how badly Somerby wishes to interpret them.

I dunno. The bottom kids are all getting an extra year of school. Counting them as 4th graders seems wrong.

It isn't necessarily "wrong." It just makes it harder to compare Grade 4 scores from states which retains a lot of third graders to the Grade 4 scores from other states which don't.

There's a built-in statistical advantage to the states which hold third graders back.

Pingback: Column: How Mississippi gamed its national reading test scores to produce ‘miracle’ gains

Pingback: Hiltzik: Mississippi's suspect studying check scores - News of The Times

Pingback: Hiltzik: los puntajes sospechosos de las pruebas de lectura de Mississippi - Notiulti

Pingback: Column: How Mississippi gamed its national reading test scores to produce 'miracle' gains | West Observer

Pingback: Column: How Mississippi gamed its national reading test scores to produce 'miracle' gains - Technocharger

Pingback: Hiltzik: Mississippi's suspect reading test scores - Techno Blender

Pingback: Hiltzik: Mississippi's suspect reading test scores - Quick Telecast

Pingback: Column: How Mississippi Gamed Its National Reading Test Scores To Produce 'miracle' Gains | Binghamton Herald

Pingback: Column: How Mississippi gamed its national reading test scores to produce 'miracle' gains - Edinburg Post

Pingback: Хилтзик: подозрительные результаты теста на чтение из Миссисипи - Nachedeu

Pingback: हिल्ट्ज़िक: मिसिसिपी का संदिग्ध रीडिंग टेस्ट स्कोर - News Archyuk

Pingback: ヒルツィク:ミシシッピ州の容疑者、テストの点数を読み取る - Nipponese