I've long argued that it takes about a year for Fed interest rate hikes to slow down the economy and affect inflation. This means that Fed hikes have had little impact so far, but will start to have one over the coming year. Jason Furman reviews the evidence and he isn't buying it:

In sum, just about every way monetary policy affects the economy reached its current level of tightness over a year ago. Just about everything you would expect to be affected by monetary policy (housing, nonresidential structures, net exports) was--but in the past.

— Jason Furman (@jasonfurman) June 28, 2023

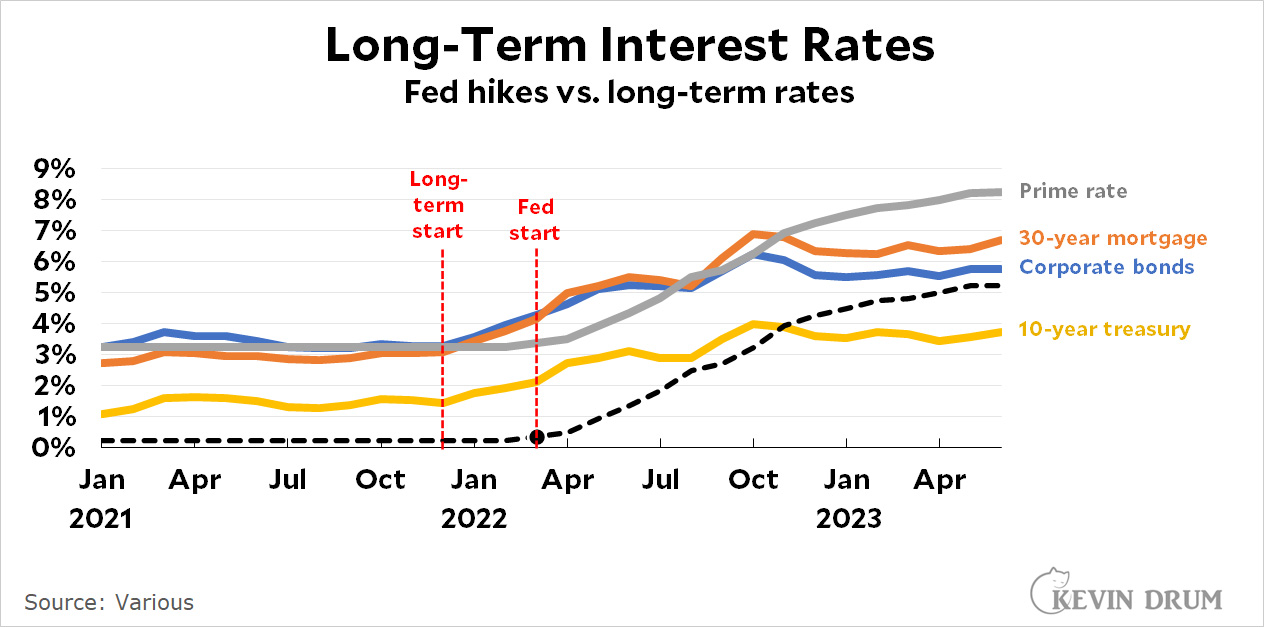

Furman's argument is fairly standard: Fed interest rates don't directly affect the economy. They affect it mostly by pushing up long-term rates, which in turn affect housing, investment, commercial loans, and so forth. That initially happened via expectations even before the Fed started hiking and had finished its work by the end of 2022. So tightening is all in the past. There's something to this:

The Fed started raising interest rates in March of last year, but longer-term rates had already started to rise a little bit a few months earlier. These rates continued to climb through October but have since mostly flattened out. Their job is done.

The Fed started raising interest rates in March of last year, but longer-term rates had already started to rise a little bit a few months earlier. These rates continued to climb through October but have since mostly flattened out. Their job is done.

Can this be right? If it is, it means that "long and variable lags" these days take about six months from the very first hint of interest rate hikes. Hell, the Fed has continued raising rates by a couple of points since October, but if Furman is right this has had no effect at all. Markets had long since incorporated that expectation and simply didn't respond.

So could the Fed have just gone on vacation starting in October? Was the increase since then from 3% to 5% necessary? Would any further hikes have any impact?

The best I can say is that although this affects my beliefs, I don't think it overturns them entirely. Empirical evidence still suggests strongly that Fed hikes take longer than this to work their way fully through the economy, especially when it comes to inflation—which is one of the most stubborn economic measures to respond to tightening.

So if I had to update my priors, I'd now say that (a) Fed hikes probably started affecting inflation a few months ago, earlier than I would have thought, but (b) there's still tightening in the system that will reduce inflation for the rest of the year. We don't need any more.

The Fed apparently thinks they can use rates like a thermostat to dial down price pressures. There is more to the world & national economies than interest rates. And ceteris is never paribus.

One of the issues that central banks everywhere, not just the Fed, face is that interest rate adjustments are most effective when combined with appropriate tax and spending policies, but legislatures seldom cooperate or coordinate with their country's central bank.

I doubt that the Fed even believes that they can control inflation like a thermostat by adjusting rates at this point. I think that, like Kevin, they refuse to see one of the biggest sources of inflation being excessive profit taking by corporations in industries with far too little competition and continue to assume it is that those damn workers are just getting too uppity because wage pressure is the only frame of reference for the sources of inflation that they've had for decades.

The baked in assumption that upward pressure from increases in workers' wages is the primary cause of inflation creates a huge blind spot such that other sources of inflation are just completely ignored.

"Prior" is an adjective, not a noun, you have to specify what is "prior". I know what you're talking about but most people don't.

It's like you read Furman and decided that there might be a position between your dogmatic understanding and what Furman wrote in his thread, because while he shows a lot of evidence to support his thesis, your lying eyes will not approve.

OT: A very long analog series, by way of 12-month moving average of total vehicle miles traveled, suggests WFH has stabilized, contrary to what you keep insisting is about to change.

Using Furman as a counterexample for 'dogmatic' is pretty ironic.

Both Kevin and Jason Furman throw up a lot of charts, often without great context, and ask readers to agree with their assumptions because CHARTS!

Furman is similar to Summers in that he gets alot of good press for being wrong. Hes popular and people like to nod along.

Is there competing evidence?

Furman is showing contemporaneous data. KD is relaying macro dogma stemming from Friedman's 1959/60 book bringing up long and variable lags, which aggregated historical cycles. The economy, in large part (I suspect) due to technology, is not the same in 2023 as it was in 1960. Aggregating historical data with more modern data will hide the changes that technology has brought.

But if you're relying on Friedman, then, let's look at what happens to the M2 supply with rate changes. What do you see? M2 started going down two months before the first fed increase. That was the primary basis for Friedmans' claim of long and variable lags.

And just in case you wanted to make the argument that the Fed balance sheet had an effect, let's look at the M2 supply overlaid with the Fed's balance sheet. Again, the M2 supply contracted before the Fed's balance sheet was reduced.

Therefore, I ask you, do you believe the contemporaneous data or are your eyes lying to you?

I would be open to the argument that due to the exogenous effects (of inflation) being removed, there is an illusion of immediate aggregate demand changes that coincided with the post-pandemic bump. If so, you have to argue against Friedman on his belief that there was little to no lag in aggregate demand from rate changes.

Please feel free to do so.

The entire premise of this post continues to be wrong.

I'm tired of saying it.

FTFY

"In other words, it's COVID. It's supply chains. It's shortages. It's oil prices."

It's extra markup by companies.

"In other words, it's COVID. It's supply chains. It's shortages. It's oil prices."

I partially agree. Certainty, the items you mention are a significant portion of the root cause of inflation: however, policy also played a role.

First, here are other similar countries excluded from the graphic that have very different outcomes. For example South Korea, Switzerland and Singapore: they were impacted by global supply chain issues and energy prices, yet did not experience the inflation.

https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/KOR/south-korea/inflation-rate-cpi

https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/SGP/singapore/inflation-rate-cpi

https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/CHE/switzerland/inflation-rate-cpi

Second, if you want to look at the graphs, contrast the shape of the lines for the US, against Italy or the UK. The three countries started about the same place in terms of inflation, yet the US had much earlier inflation than Italy or the UK. Further, our inflation has dropped much more rapidly. Yet, the US, Italy and UK faced similar supply chain issues, and similar gas prices. How do you explain these significant differences in terms of inflation?

Third, while you might disagree, there are several well known economists/'experts that attribute some of US inflation to policy.

There are more differences between countries than just government policies; the structure of economies differs substantially — nature and volumes of imports/exports, proportions of domestic agriculture/manufacturing/services/financial, patterns of consumption, and more.