The New York Times suggests that the war against woke isn't doing any better than the war against Christmas. Even Republican voters are tired of it:

When presented with the choice between two hypothetical Republican candidates, only 24 percent of national Republican voters opted for a “a candidate who focuses on defeating radical ‘woke’ ideology in our schools, media and culture” over “a candidate who focuses on restoring law and order in our streets and at the border.”

Vivek Ramaswamy may be a no-hope candidate for the Republican nomination, but he made his name as an anti-woke doomsayer. That was only two years ago, but today he says he's already moved on:

In an interview, Mr. Ramaswamy said the evolving views of the electorate were important, and he had adapted to them....“At the time I came to be focused on this issue, no one knew what the word was,” he said. “Now that they have caught up, the puck has moved. It’s in my rearview mirror as well.”

Law and order and border security have become stand-ins for “fortitude,” he said, and that is clearly what Republican voters are craving.

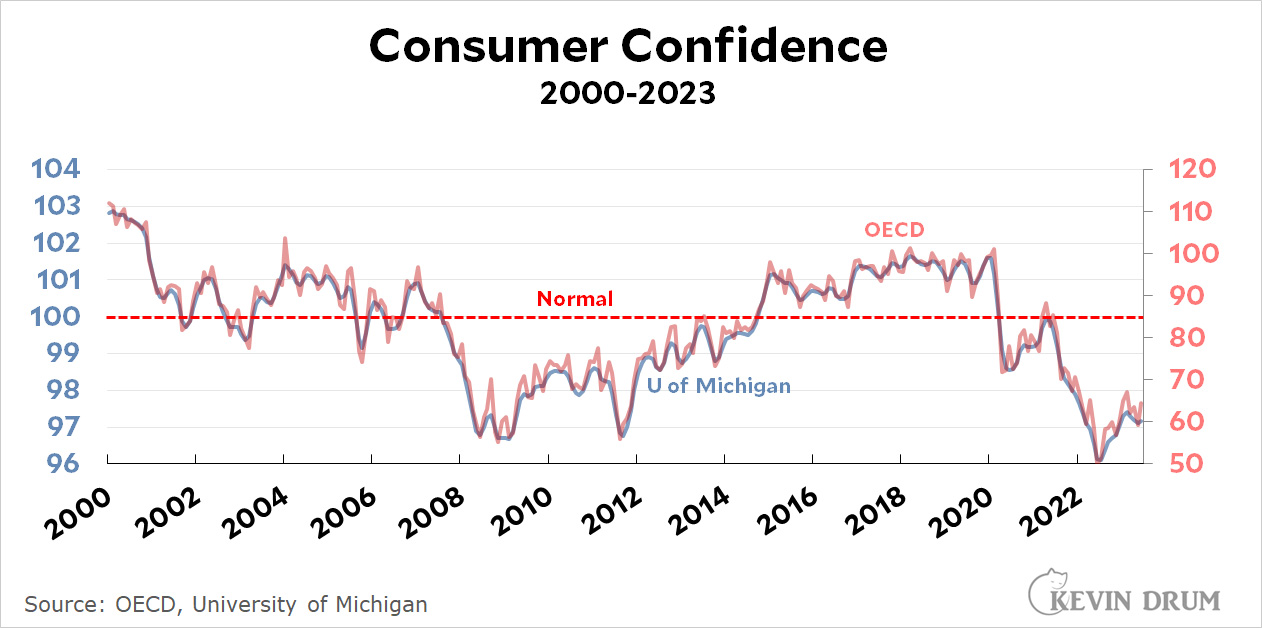

Among Republicans, the border is pretty clearly the issue with the most legs. It's not always the top concern of the moment, but year in and year out it's always near the top of the list. And it's at record highs this year:

Donald Trump might not be the smartest guy in the room, but he has a native shrewdness about people. Immigration was his top issue on the day he descended from Trump Tower onto our TV screens, and it's still his top issue today.¹

Donald Trump might not be the smartest guy in the room, but he has a native shrewdness about people. Immigration was his top issue on the day he descended from Trump Tower onto our TV screens, and it's still his top issue today.¹

¹Aside from complaining about how badly everyone treats him, of course.