You may have heard of the replication crisis. It mostly refers to studies in the social sciences that get a lot of media attention when they're first published but then fail to produce the same results when other researchers try to replicate them. The reason it's become a crisis is that a lot of studies fail to replicate, calling into question the whole enterprise of the social sciences.

But one problem with this is that it's hard to replicate a study. Small things can make a big difference sometimes, and doing a precise replication isn't always easy. A recent paper shows this pretty dramatically. First off, here's what the researchers were trying to replicate:

The study was published in 2021 and investigated an association of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and chronic lower respiratory disease (CLRD) exacerbation in a population with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) and CLRD.

This is no dashed-off social science experiment. This is a big and very serious medical study with very specific methods and goals. What's more, the researchers weren't trying to replicate the whole thing. They were only trying to replicate one little part: deciding which patients to include in the study. Here are the criteria:

New users of GLP1-RA add-on therapy aged more than 17 years with at least 1 outpatient or 2 inpatient encounters with T2D and CLRD in the year before the index date with no prior insulin or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors exposure and no prior type 1 diabetes mellitus, cystic fibrosis, lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, conditions requiring chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy within a year or pregnancy at the index date.

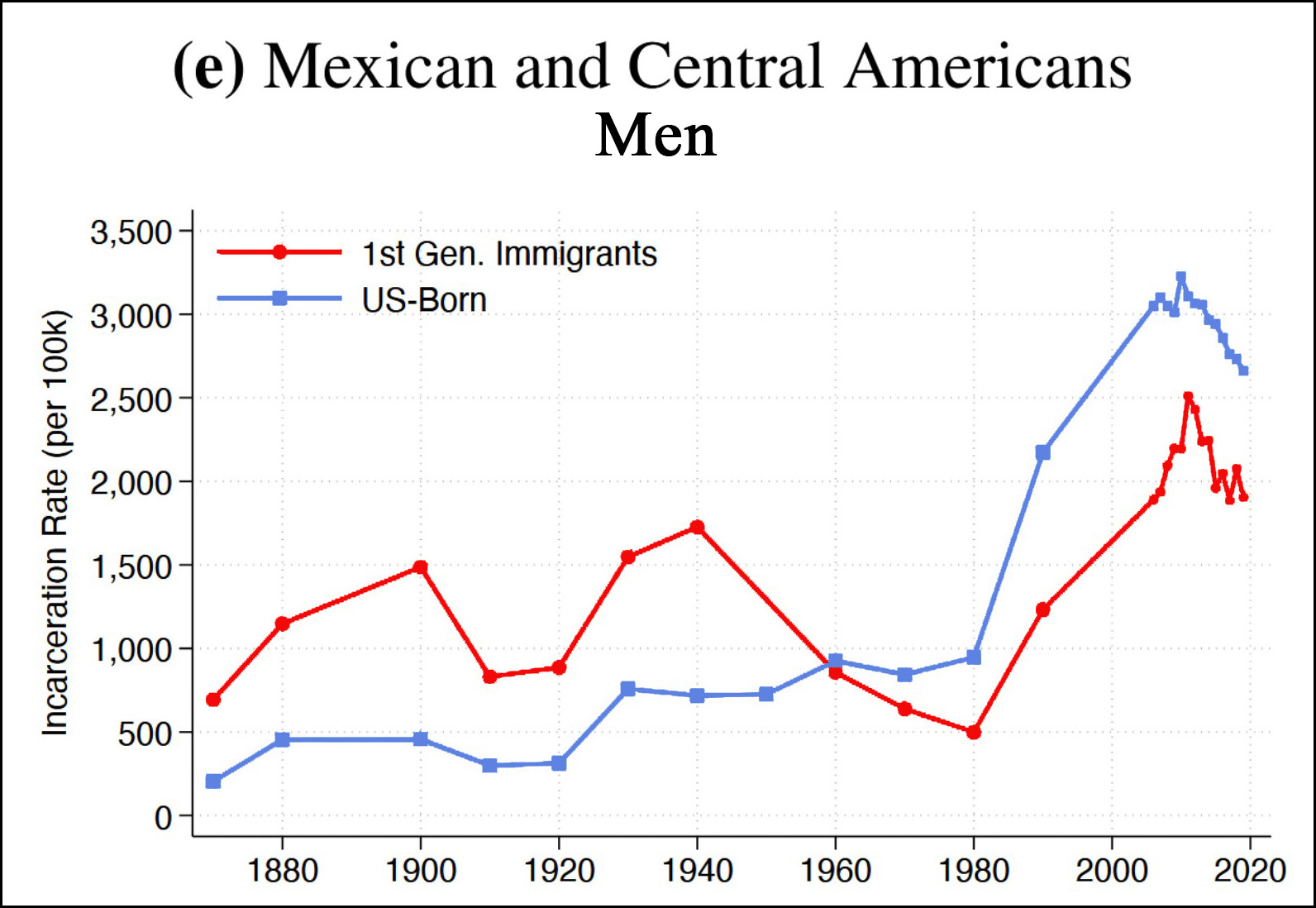

Got that? The researchers gathered together nine teams of qualified experts whose only task was to slice and dice a database to come up with a cohort of patients who met the inclusion criteria. The results were dismal. Interpretations of what the criteria meant were all over the map and none of the nine teams came close to matching the cohort from the original study. They couldn't even come close to agreeing on how many people were in the cohort:

The green bars represent patients chosen by both the original study and the team of replicators. The largest overlap is only 35%. The number of people chosen for the study ranges chaotically from 2,000 to 64,000. Every team deviated from the inclusion criteria in the original study in at least four different ways.

The green bars represent patients chosen by both the original study and the team of replicators. The largest overlap is only 35%. The number of people chosen for the study ranges chaotically from 2,000 to 64,000. Every team deviated from the inclusion criteria in the original study in at least four different ways.

So replication is no walk in the park, even in the hard sciences where the procedures are presumably more concrete. But if replication is this hard, what chance do we have of properly replicating anything?

Wastewater measurements are now about the same as they were at this time in both 2021 and 2022. In 2021 that led to a huge outbreak later in the year. In 2022 it led to nothing.

Wastewater measurements are now about the same as they were at this time in both 2021 and 2022. In 2021 that led to a huge outbreak later in the year. In 2022 it led to nothing.