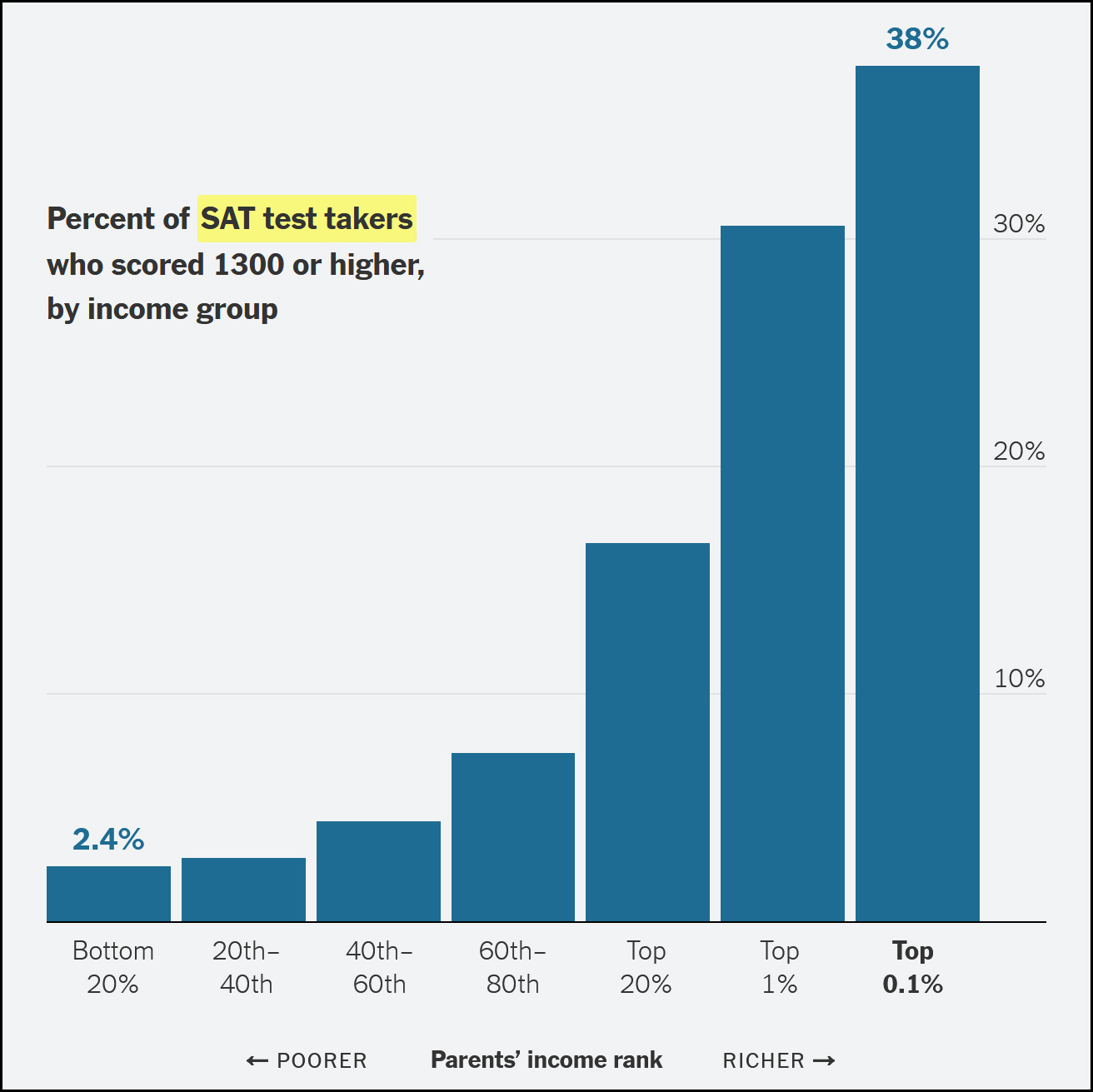

Jason Furman draws our attention to a new paper that analyzes the effect of the 2017 business tax cut. Long story short, the authors find that cutting taxes increased investment.

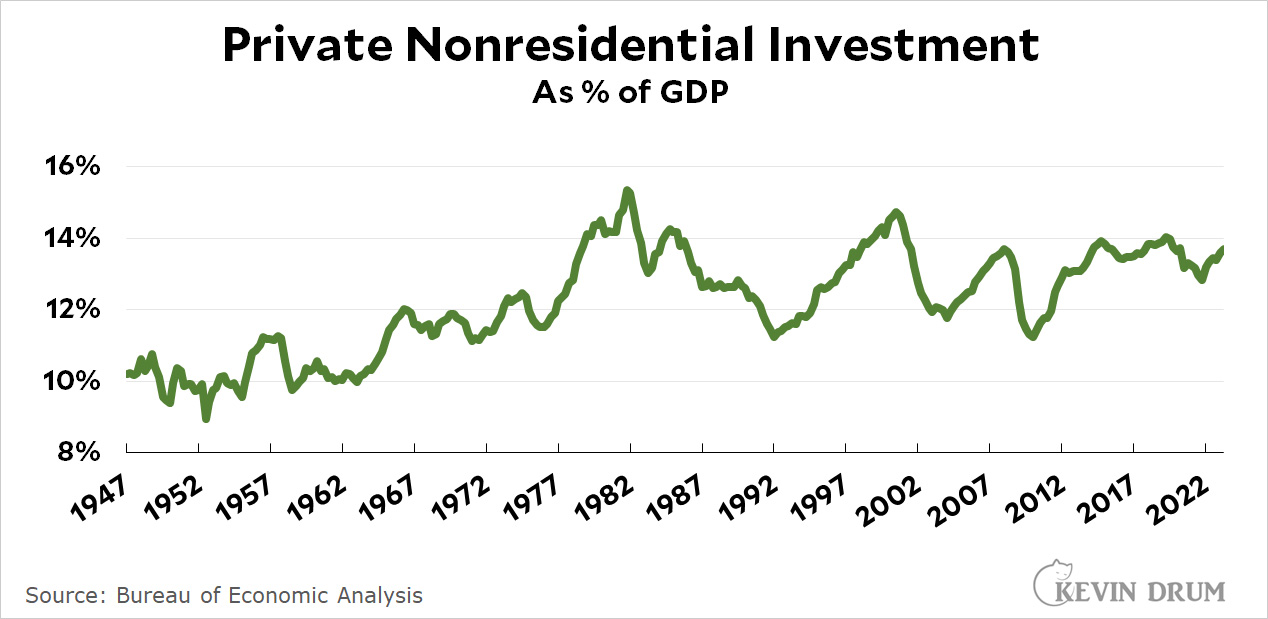

I'm skeptical of this, and I'll show you why in three charts. First up is a chart from the paper itself showing, as promised, that corporations with bigger tax cuts also invested more:

But take a closer look. Every single company got a tax cut. However, aside from four outliers on the upper right, not a single company increased investment by any significant amount. Most of them reduced investment. The trendline may indeed be up and to the right, but the overall amount of increased investment is negative.

But take a closer look. Every single company got a tax cut. However, aside from four outliers on the upper right, not a single company increased investment by any significant amount. Most of them reduced investment. The trendline may indeed be up and to the right, but the overall amount of increased investment is negative.

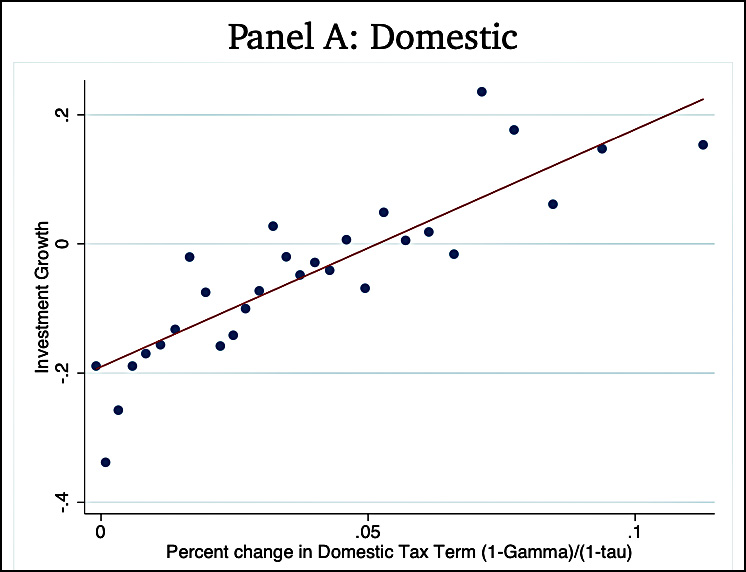

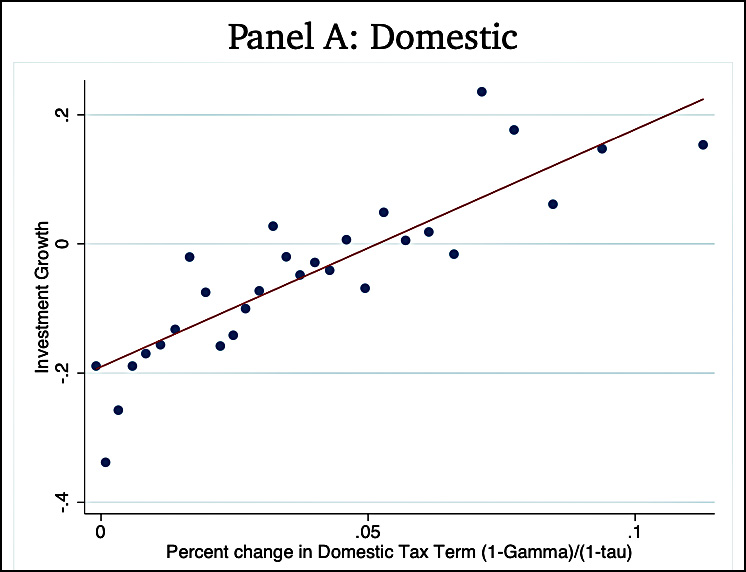

Next up is business investment since the end of the Great Recession:

This is a broad look, so you might not expect to see a big impact from the tax cut. But in fact you see no impact from the tax cut. Surely there ought to be something, even if it's small?

This is a broad look, so you might not expect to see a big impact from the tax cut. But in fact you see no impact from the tax cut. Surely there ought to be something, even if it's small?

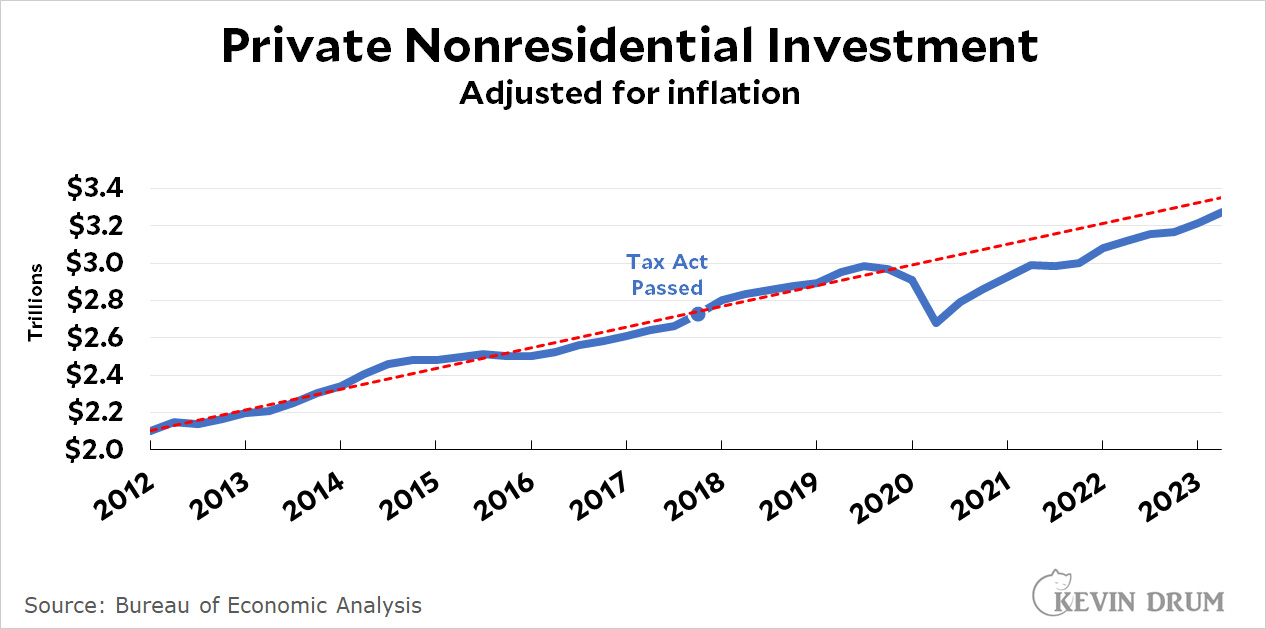

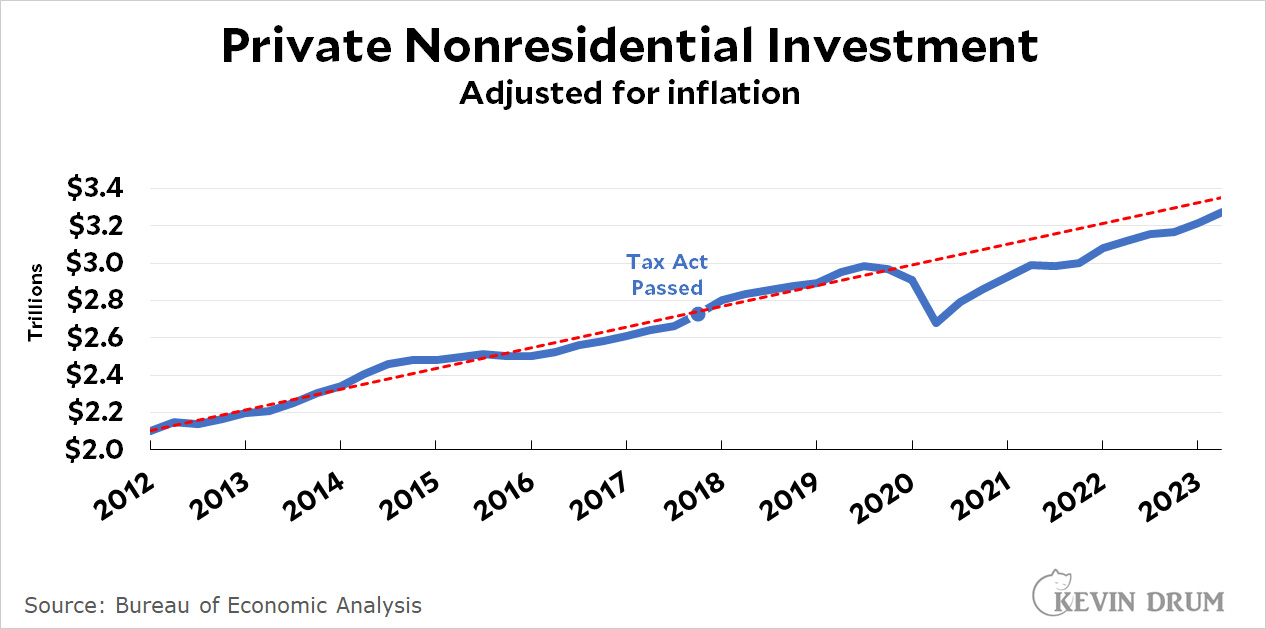

Finally, here's a long-term chart showing business investment since 1947:

The amount of business investment varies enormously from year to year, and this plainly has nothing to do with taxes. Even if tax cuts do have an effect, they are surely minimal compared to the normal ebb and flow of investment.

The amount of business investment varies enormously from year to year, and this plainly has nothing to do with taxes. Even if tax cuts do have an effect, they are surely minimal compared to the normal ebb and flow of investment.

To summarize: (a) most companies reduced investment following the 2017 tax cut, (b) overall business investment didn't budge from its trendline following the cut, and (c) business investment varies so strongly from year-to-year that a small tax effect would be unnoticeable even if there were one.

It may be that, technically, the 2017 tax cuts increased investment compared to a baseline of some kind. But even if that's so, the effect is tiny and completely washed out by normal noise.¹ Anyway you cut it, we gave up $1.5 trillion in tax revenue and increased the federal deficit by $1.8 trillion for nothing.

¹This is what the CBO projected five years ago: total increased business investment would be on the order of $20-50 billion per year, an amount too small to measure.