The New York Times is suing Microsoft and OpenAI for training their AI software on Times stories:

In a complaint filed Wednesday, the Times said the technology companies exploited its content without permission to create their AI products, including OpenAI’s humanlike chatbot ChatGPT and Microsoft’s Copilot. The tools were trained on millions of pieces of Times content, the suit said, and draw on that material to serve up answers to users’ prompts.

....Tech companies building generative-AI tools have generally argued that content available on the open internet can be used to train their technologies under a legal provision called “fair use,” which allows for copyrighted material to be used without permission in certain circumstances. In its suit, the Times said the fair use argument shouldn’t apply because the AI tools can serve up, almost verbatim, large chunks of text from Times news articles.

I've expressed my opinion before that mere training is indeed fair use. If things were otherwise, everybody would be liable who had ever learned something from a Times article and then used it to publicly form an opinion or analysis.

But routinely serving up large verbatim chunks of stories is a different thing. This got me curious, so I asked GPT 4 about the Times' coverage of the James Comey letter regarding Hillary Clinton at the tail end of the 2016 presidential campaign:

In October 2016, the New York Times and other sources reported on a letter from then-FBI Director James Comey regarding the reopening of the investigation into Hillary Clinton's use of a private email server.

....The letter by Comey was criticized for its vagueness, as it acknowledged that the FBI did not know the contents of the emails in question or whether they were relevant to the investigation.

Etc.

That seemed fine, so I asked what the Times had actually said:

I'm unable to access the full content of the New York Times article from October 2016 regarding James Comey's letter about the Hillary Clinton email investigation. For detailed information and to read the article, I recommend visiting the New York Times website or accessing their archives directly.

This is just one query and might not represent typical behavior. But if it does, it appears that GPT 4 reads stuff from the Times and then summarizes it briefly the same way any human would do. Unless there's a lot more to it, including the ability to essentially act as a substitute for reading the Times, I still don't see anything wrong here. Treating this as copyright infringement would set an enormously dangerous precedent.

POSTSCRIPT: The lawsuit is here. It includes some examples of large-scale copying, mostly from Bing and mostly produced by laboriously asking for single sentences or paragraphs at a time. I'm skeptical that this is truly serious infringement since it's so artificial, but I can at least imagine a judge enjoining Microsoft from reproducing so much content. Overall, though, I remain unconvinced that training, summarization, and brief excerpts should be barred.

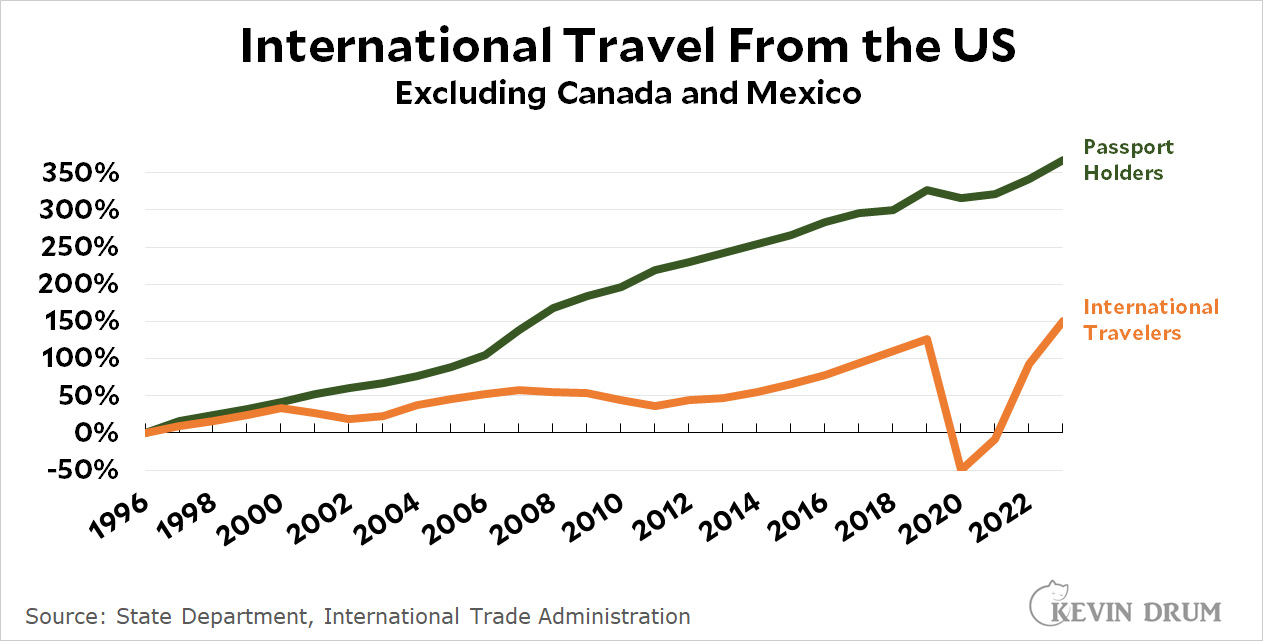

During the pandemic, international travel collapsed but passport holding just kept on increasing at the same rate as always. Odd. I suppose part of this might be attributed to the popularity of having a passport as ID rather than for travel. Is that a thing?

During the pandemic, international travel collapsed but passport holding just kept on increasing at the same rate as always. Odd. I suppose part of this might be attributed to the popularity of having a passport as ID rather than for travel. Is that a thing?