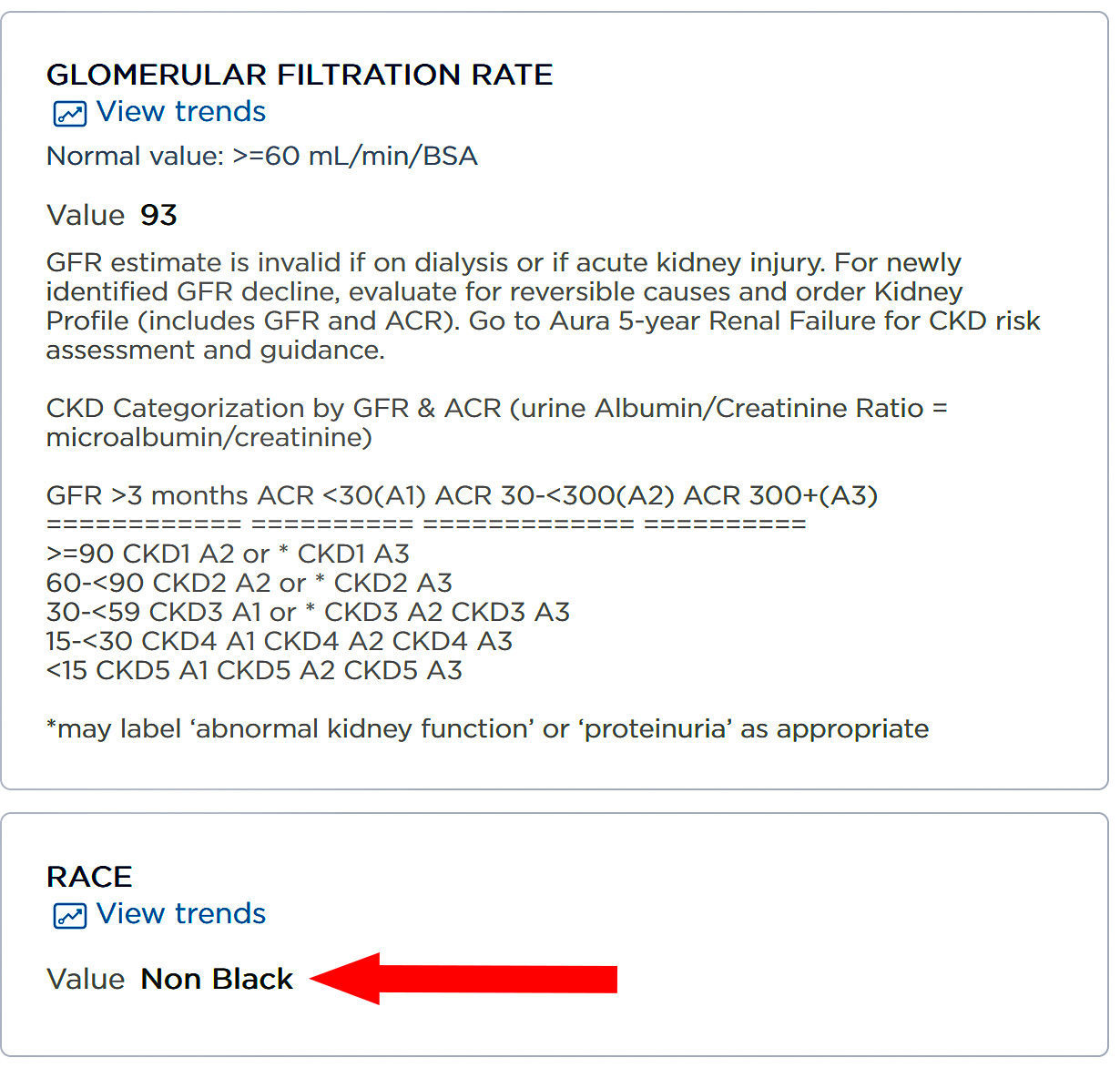

Every month I get a big pile of blood tests. Here's one of them:

This result happens to be from May 26, 2020. A year later the "Non Black" designation suddenly disappeared.

This result happens to be from May 26, 2020. A year later the "Non Black" designation suddenly disappeared.

Why? Well, there's now a note that says "GFR estimate is by the CKD-EPI 2021 equation." I never noticed that before, but today Atrios points to an AP article that explains a change to the standard measurement of GFR:

At issue is a once widely used test that overestimated how well Black people’s kidneys were functioning, making them look healthier than they really were — all because of an automated formula that calculated results for Black and non-Black patients differently. That race-based equation could delay diagnosis of organ failure and evaluation for a transplant, exacerbating other disparities that already make Black patients more at risk of needing a new kidney but less likely to get one.

A few years ago, the National Kidney Foundation and American Society of Nephrology prodded laboratories to switch to race-free equations in calculating kidney function. Then the U.S. organ transplant network ordered hospitals to use only race-neutral test results in adding new patients to the kidney waiting list.

This story leaves out a few things. First, it's true that an old GFR test used a racial adjustment that increased Black scores by 21% compared to whites. In 2009 some researchers reported on a new GFR test called CKD-EPI, but they didn't conclude that the old racial adjustment was wrong. They simply found that it should be reduced slightly from 1.21 to 1.16.

A later study with a larger sample concluded that CKD-EPI was a better predictor for practically everything compared to the old test, including kidney disease in Black patients.

But the race adjustment was still there, so a 2021 study looked at what would happen if it was removed entirely. After all, as the study authors said, "race in eGFR equations is a social and not a biologic construct." They set out to prove this, and found, unsurprisingly, that if you choose a single adjustment value in the middle for both Black and white patients, you'll end up pulling the Black results down and the white results up. This was said to be "more accurate" even though it actually performed slightly worse overall.

A 2021 study in Europe that had a large Black cohort agreed. It found that "the accuracy of the 2021 CKD-EPI equation was the lowest" of the ones tested. The authors concluded that a good argument for adopting the new test was to align Europe with the US. However, a good argument for not adopting it was that "the new equation does not perform better, but worse."

But the National Kidney Foundation had already forged ahead with a fresh look at GFR testing. Initially they were cautious:

When announcing the establishment of the task force eight months ago, NKF and ASN affirmed that race is a social, not a biological, construct, but recognized that simply dropping the race modifier could introduce different biases and disparities.

By September of 2021 they had made up their minds:

We recommend immediate implementation of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation refit without the race variable in all laboratories in the United States because (1) it does not include race in the calculation and reporting, (2) included diversity in its development, (3) is immediately available to all laboratories in the United States, (4) and has acceptable performance characteristics and potential consequences that do not disproportionately affect any one group of individuals.

It's notable that nothing in this statement suggests the race-free version of the test is actually more accurate. However, the new test does accomplish what it set out to do: it now overestimates kidney disease in Black people and underestimates it in white people. This means Black patients will get more kidneys and white patients will get fewer. It's very hard to conclude from the evidence that anything else was ever the goal here.

When did science become subservient to wokeness?

I thought real scientists were better than that.

It is not science, it is medical services, which have other constraints too.

Whether what they did is justified or not can be argued, but it is not a scientific question.

Black people overall get under-treated, so correcting so they get tests that are less likely to report them only results in continued worse results.

Medicine needs a better proxy for genetics than race. Black people in particular are extremely diverse genetically.

Since race is a social construct, it's a yard stick that's poorly marked out and subject to change.

Edit: To add, *even* *if* we nailed down a precise, reliable definition of race, the genetic inference from race would still change through the normal process of evolution.

Needs yes. Has, no.

Medicine is an imprecise science. We have to use the best measures we have while always seeking better.

We probably could improve on race. For example, an adjustment that takes into account percentage of Black African ancestry would likely do better. Medical practitioners should also be aware that not all dark frizzy haired prime have African ancestry. For example, Papuans.

"The new test does have one advantage, though: it overestimates kidney disease in Black people and underestimates it in white people. This means Black patients will get more kidneys and white people will get fewer."

I'm not sure I understand this. How is this an advantage?

The increased disagnoses for black folks is probably more than compensated for by their decreased likelihood of receiving apprroproate care ... at any income level. So no; even on balance, it isn't "good."

I'm not going to touch the thing about "no such thing as race" because, somehow, we still manage to field a quite robust "racism" in this country, and how does that even work?

It's not good to balance out slower care with bigger flags?

That seems likely to produce worse results.

Blacks who do not receive appropriate care will not magically receive it because their test results are worse.

Meanwhile blacks who were receiving appropriate care will now be getting dialysis and kidney transplants, with all their associated complications, before they absolutely need them.

There's a waiting list for kidney transplants. Looking sicker gets you higher up the list.

But is Kevin really saying it’s better for blacks to get transplants in front of whites? I hope not.

I read this as mild sarcasm on the part of our genial host.

Yes indeed.

I assume this is just 1 screening test, and there are many tests that would be done before the person is declared to have renal failure and needs to go on dialyses and may be a candidate for transplant.

I could "Google" GFR or use the new Chrome AI assistant, but I really don't want to learn more about renal failure in order to confirm if my "assumption" was reasonably valid.

Background to this is that GFR is an inferred measure of kidney function, not a direct one. As far as I know there isn't an easily usable direct way to measure anybody's filtration rate, and certainly no test that can be performed as part of routine blood labs and used for screening. It's calculated from creatinine level, which itself can be subject to variation for many reasons, and its interpretation also depends on age. So I think it's kind of a blunt instrument, something that could set off a detailed testing regimen if it's in an unfavorable range.

The problem with the older approach is that it let potentially dangerous conditions among deemed Black patients go unflagged too long, which as peterlorre says is peculiarly conducive to bad outcomes for them, taken as a group. Whether the race-neutral calculation exposes deemed White patients to that kind of outcome remains to be seen.

But as a group, deemed Black patients would seem to have more to lose from a late diagnosis, because of that epidemiological pattern, than would deemed White patients, and that's not something to lose sight of.

I used to work in the CKD field, and here is some of the nuance that Kevin is missing:

- Epidemiologically, patients with African ancestry tend to have worse CKD prognosis for a whole host of kidney-related outcomes. This is due to a combination of known and unknown genetic factors as well as presumed 'environmental' effects (which includes the literal environment but also pretty much anything non-genetic that contributes to kidney morbidity and correlates with African ancestry).

- The above observation is empirically true and needs to be considered when treating patients with CKD. Historically, this all gets rolled up into a concept of the patient's race, which is used to guide treatment options.

- Positively everyone in the CKD field understands that this is a bad approximation and that it would be better to use more precise measures

- Medical genetics is really hard, and as mentioned major components of CKD disease progression are not understood.

- Consequently, it's not easy to come up with a principled drop-in replacement for race when causality isn't well understood.

- When you do come up with something better it still needs to be scrutinized in the literature, as in the studies Kevin cites. The new measure is obviously a statistic so it will improve in some areas and trail in others from the previous approach.

- Finally, the medical establishment tends to be extremely hidebound about this stuff and even when you do find something that is strictly better it's shockingly hard to get doctors to do it.

HTH.

That last one is a biggie - any more accurate measure will likely require more data collection by physicians. That wont be popular.

Thanks for this. This is the kind of topic where nuance is critical; it's important to hear from someone with real expertise in the subject.

Thanks for the explanation. The problem usually isn't measuring something like flow rate or chemical ratio. The problem is figuring out what it means in terms of health outcomes. Look at all the problems assessing BMI, and that's based on easy, non-invasive measurements you can do at home.

It's a real problem when you have a fragmented medical system. People move. Their doctors move. They change health insurance plans. Add in medical privacy issues, and it's hard to tell what a measurement made ten years back meant in terms of health today.

I wouldn't touch this topic with a 10 foot pole. Kevin shouldn't have either. As Peterlorre explains above, there is a lot of nuance in deciding who of the 123,000 people waiting for a kidney gets the 17,000 kidneys that become available each year. Until the 17,000 shows signs of obvious racial bias, Salamander's comment above probably holds true: any advantage black people get from this formula change is probably cancelled out by all the disadvantages black people face in getting and paying for medical care at all, as well as the geographic bias that favors white people. (Kidneys that become available in, say, North Dakota are overwhelmingly likely to go to another Upper Midwesterner... and that region is pretty pale.)

So until I personally know someone waiting for a kidney, I'm not going to worry about this at all and assume the people making the decisions about handing them out is doing so fairly.

Until...

Dude, it does. Black people are less likely to be assigned a kidney.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10057682/#:~:text=A%20subsequent%20prospective%20cohort%20study,donor%20transplant%20than%20White%20patients.

You coulda just googled it. Google hasn't gotten that bad yet.

There are real medical differences that can be correlated, however inperfectly, with the traditional (socially constructed) racial classifications. People of sub-Saharan African descent are far more likely to develop sickle-cell anemia than those of European descent. It would be medical malpractice to ignore differences such as this. These things should be correlated whenever possible with genetics rather than "racial" classifications - the gene for sickle-cell has been identified, but apparent those for the differences in renal disease have not (if it is genetic and not environmental). The differences which are correlated with the racial classifications can't be ignored just because the classifications are mostly social constructs.

On the other hand there are presumably fallacious medical practices or beliefs, such as that black people feel pain less than white people, which should be eradicated (is there an objective study on this?). It may be hard to distinguish these beliefs from differences based on good evidence.

"...race is a social construct...".

Looking at humanity as a whole, yes. The races we think of are actually samples of the diversity of humanity not the whole range of diversity. Between those stereotypical types are a whole lot of intermediates and types that don't fit into those 'races'.

In addition, there are many genetic attributes that a spread across humanity in patterns that defy the usual racial boundaries. Africans classified as "black" based on appearance are more genetically diverse than all the rest of humanity combined.

However, people of African ancestry in the Americas are nearly all from limited areas of west Africa, and are far less genetically diverse than sub-Saharan Africans overall. So it may make sense to view this group of people as perhaps having medically significant medical differences as a whole, if the evidence supports this.

How do you calculate the test results for a bi-racial person? Do you take an average? I've read that the average black person in the US has about 25% white DNA. Should the results be recalculated proportionally for that?

This strikes me as a strong argument for the decision Kevin is unhappy with, and especially so looking forward, as the more mixed younger population moves into adulthood.

Exactly. Do we have to classify by darkness of skin to make Kevin happy? Or is there actually some genetic marker or set of markers that could be taken into account in the formula. That is the actual scientific way to do it, rather than decide where to put Zendaya in Black or non-Black.

To use the 2009 formula, you have to classify the bi-racial individual as either “black” or “not black.” In contexts where the formula is required to be used, taking an average is not an option.

Paging Doctor McCoy. Doctor Leonard McCoy, please report to the Nephrology department: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ssq8wHAx4nE ...

I don't know, but I feel pretty confident that the genes that affect skin pigmentation and facial features do not have much influence on kidney disease or tests for kidney disease.

We live in a time where we can map the human genome. I would think it would not be too hard to get a genetic readout, and correlate the test result with that, taking note not of "race" but of whether a few specific genetic variations are present.

Let's not forget that because of the one-drop rule, lots of people who are "black" are of very mixed parentage and may not have these kidney specific variations.

By the way, reporting the same score for all patients STILL allows doctors to note potential genetic variations and act accordingly. Transparency is good.

Meanwhile: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-68710229.amp