Matt Yglesias takes on the "Deaths of Despair" meme today. It originates with Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who wrote about it a few years ago, and, as Matt points out, it's somehow survived despite a series of statistical examinations that have left it in tatters. If you adjust for age, it becomes less dramatic. If you adjust for geography, it's limited largely to the South. If you break it down by education, it's largely a phenomenon of high school dropouts. Matt continues:

The rise in deaths of despair turns out to overwhelmingly be a rise in opioid overdoses. This increase is not happening in European countries that have not only been buffeted by the same broad economic trends as the United States, but are also seeing the rise of right-populist backlash politics.

The obvious explanation is that the US and Europe have very different laws governing pharmaceutical marketing....This is all actually pretty clear cut and has been said before, but critics must not be saying it clearly (or rudely) enough because the narrative just keeps trundling forward.

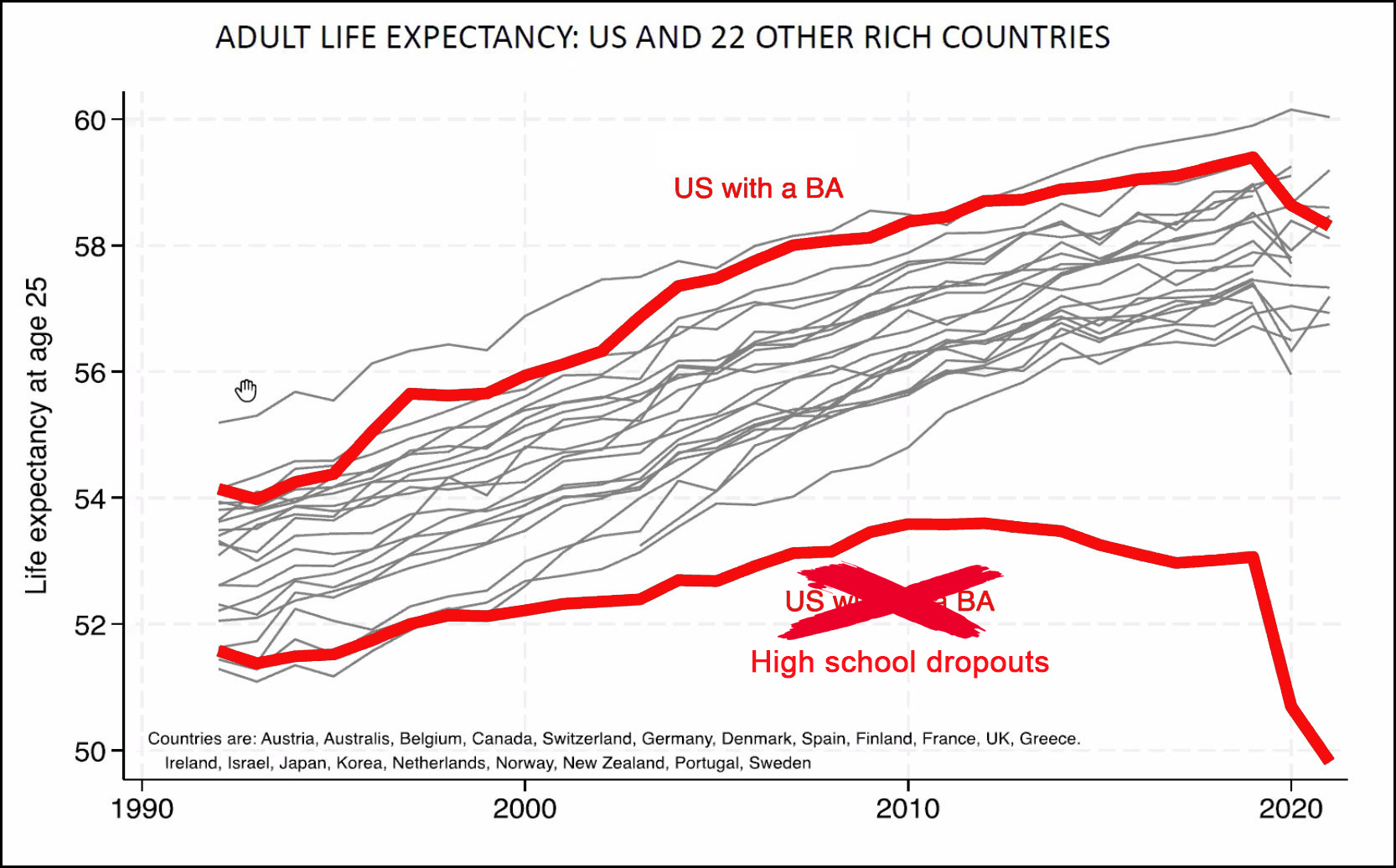

I agree with Matt's larger point: the deaths of despair narrative doesn't really seem to hold water, and it's worth saying this bluntly. But is it really just about opioid overdoses? Let's revisit a recent chart from Case and Deaton:

US life expectancy has taken a big hit compared to other rich countries, but it turns out this is largely due to reduced growth rates among high school dropouts. The slowdown started around 1998 or so, which means it has to be related to something that changed in 1998 or earlier. Something that changed more for high school dropouts than for college grads.

US life expectancy has taken a big hit compared to other rich countries, but it turns out this is largely due to reduced growth rates among high school dropouts. The slowdown started around 1998 or so, which means it has to be related to something that changed in 1998 or earlier. Something that changed more for high school dropouts than for college grads.

Now let's take a look at drug overdoses from a recent RAND study:

There's a huge difference in the rise of opioid overdoses between college grads and high school dropouts. And the OxyContin revolution started in 1996, which makes it a natural candidate for a trend that began in 1998.

There's a huge difference in the rise of opioid overdoses between college grads and high school dropouts. And the OxyContin revolution started in 1996, which makes it a natural candidate for a trend that began in 1998.

But the difference is fairly modest until around 2015, when fentanyl hits the scene. Between 2000 and 2015 the difference rose by about 30 per 100,000. Then, in just the few years from 2015 to 2021, it rose by about 45 per 100,000. Thus we'd expect life expectancy growth for high school dropouts to slow down between 2000 and 2015, and then to really slow down from 2015 to 2021.

And this is roughly what happened—until COVID hit and the bottom fell out of everything. So the only remaining question is this: Is the increase in overdose deaths among dropouts (bottom chart) enough to account for their stagnant life expectancy (top chart)? This is something that only an expert can answer. Any volunteers?

I think you have to add in obesity at some point, which, in my expertise in guessing, I'd guess is higher among high school dropouts.

It’s hard to wrap my head around these numbers. The population is over 300M so this is 240,000 deaths a year for the last year in the chart. That is a gigantic number.

On the other hand, 80 per 100,000 is less than 1 per 10,000. I don’t know a thousand people so I would likely not hear about even one of these deaths except for reading the news.

It is a huge number. You might not know any of them, but it's very likely that one (or some) of the people that you know do know one (or some) of them.

I remember something like that after 9/11. As I recall, most Americans did not know the victims personally, but a high percentage of Americans knew someone who knew a victim.

The attack in Israel seemed so far away. Then I found out a neighbor knows a woman who is missing. Another friend has family who narrowly escaped militants who raided their house. Thinking about those connections changes the way you think about what happened.

One of the downsides of focusing on data is that it distances us from the reality of human suffering. I got that sense reading the Yglesias article -- it seemed these human lives were an abstraction, and I felt a denial of the despair that no doubt exists for many of the "gigantic number" of people who are dying.

Yglesias:

"The obvious explanation is that the US and Europe have very different laws governing pharmaceutical marketing." *

That is huge news! All this time we thought people were dying out of despair. But nope! It's just a quirk of marketing!

* Yglesias doesn't cite a single piece of evidence for the assertion he makes at his personal blog. I'm sure that will be coming in his peer-reviewed article for The Lancet.

Opioids are handled/prescribed far for more liberally in the US than in other high income countries. This isn't remotely controversial:

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/8/8/16049952/opioid-prescription-us-europe-japan

(Why, one might almost be tempted to think that America's tradition of for profit medicine and pharma rent-seeking cause problems!)

My point was not to dispute that Americans take more opioids.

It's that Yglesias argues against the idea that Americans could be suffering from despair. That's his conclusion.

Maybe we'd all be happy campers if the evil pharma companies just stopped their marketing.

The possibility that Americans are disproportionately suffering from despair -- and disproportionately consuming opioids -- seems to escape his analysis.

I think there's strong reason to think our society is not like other countries' in ways that go far beyond laws governing pharmaceutical marketing. Forgive me for believing the problem we see in those graphs is bigger and more complex than he's willing to admit.

Re: drug marketing. I'd be overjoyed to have an end to the literally dozens of drug ads that come on, often in 5 minute blocks, on the stations I watch. The joyous elderly folks, the dancing fat women, and spare me the couples in side by side bathtubs in the middle of the forest!

Heck, I'd even put up with more "tactical sunglasses", gintzu knives, stick on outdoor security lights, and 100-piece cooking pan sets to get rid of the drugs.

It's that Yglesias argues against the idea that Americans could be suffering from despair. That's his conclusion.

As I think you probably know, Yglesisas isn't concluding Americans "couldn't be suffering from despair." His conclusion, rather, is that the famous Case and Deaton paper blaming the decline in US life expectancy on "despair" is wrong. From what I can see, most people who have done a deep dive into the statistical evidence on this—Kevin Drum—among them—appear to share Yglesias's view.

I happily admit to a total lack of expertise in this, though I feel like I understand the basic criticisms of Case and Deaton's take.

In reading around, I found an argument that the issue is not just opioids but also cardiovascular disease. (Dylan Matthews at Vox I think). Which I think in laymen's terms means, eating mostly fast food and never exercising. Yes?

Yglesias is saying the "deaths of despair" narrative is wrong and the "deaths from pharmaceutical marketing" narrative is correct. How does he reach the conclusion? By assuming that the spike in deaths from ODs is not attributable to despair but to laws regulating Big Pharma practices. He also looks at economic data to downplay differences between America and Europe, in the process assuming despair must be caused by economic factors rather than a host of other possible causes.

What about the rise in rates of death from suicides and liver disease? They don't seem to count because those rates haven't risen as fast as rates of OD deaths. How convenient to wave away evidence like that because it doesn't fit your own narrative.

Yglesias is saying the rise in the death rates among certain groups of Americans is attributable to one cause:

"The obvious explanation is that the US and Europe have very different laws governing pharmaceutical marketing."

"The increase in opioid deaths is about prescription drug policy and the rise of fentanyl."

His analysis is 100% focused on the supply side. There is a demand part of that equation and the reasons that certain Americans have been increasingly taking opioids and other drugs is unexplained. Despair seems as valid a possibility as any.

I'm not here to defend Case and Deaton. Maybe, to be generous, Yglesias raises a few good questions. But his assertion that he has disproven the "deaths of despair" narrative is wrong.

I'm not here to defend Case and Deaton. Maybe, to be generous, Yglesias raises a few good questions.

I'll take your subtle goal post movement as a sign you realize your arguing for an untenable position, but stubbornness prevents you from acknowledging you're mistaken.

But his assertion that he has disproven the "deaths of despair" narrative is wrong.

Look, I also get this: you're a liberal and like most liberals you advocate Danish-style social democracy. I do, too, as it happens! But we mustn't let that preference cloud our judgment. A careful examination of the data makes it abundantly clear the "deaths of despair" narrative is bogus. I'm going with Kevin on this one:

But you do you!

What is this "despair" and how does it kill people? Maybe if you substitute "depression"-- an actual malady that, yes, is known to kill (often via suicide) this would make more sense.

One MIGHT be tempted to think that. Until one read the (IMHO sorry and sordid) story of US "patient advocates" for pain opiates...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8646865/

The difference is not for-profit medicine, it is America's belief (sometimes, but not ALWAYS positive) that no one should ever have to listen to an expert if what the expert is saying is not what you want to hear.

Snark all you want, but European countries do tend to have lower opioid prescription rates than the US.

Perhaps it's because of pharmaceutical marketing in the US. Perhaps it's because European countries have socialized medicine, including more access to coverage for addiction treatment (an opinion piece in the Lancet put forward that idea last year).

(In fact, if socialized medicine is a major factor, that would account for the concentration of deaths among people without HS diplomas in the US. That's exactly the group that is unlikely to have access to health insurance.)

I am not an expert.

But....80 out of 100,000 is only .08% of the population.

If the change in life expectancy between the 2 groups is roughly 3.5 years (expansion of the gap from 1990 to 2018) , its hard to imagine even a massive change for the .08% having a noticeable impact on the total change. But lets see.

Lets overestimate and say that the average overdose death cuts 60 years off a life: 60 × .08% = .048 years off the lifespan of the total group.

0.048 years is roughly 1.3% of the total 3.5 year discrepancy that we are trying to change. This does not appear significant.

It is possible that this drug use has a much broader impact on those that do not die of overdoses.

For reference, infant mortality in the US is 5.4/1,000. This overdose group is 0.8/1,000.

Again, I am not an expert.

Apples to oranges.

It's .08% of total population not .08% of deaths.

The Overall death rate is 715/100,000 (for 2019)

So Opioid deaths are over 10% of all deaths, maybe.

This https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db395.htm doesn't show Opioid deaths, but maybe they are included in "unintentional injury"

You can look at it as an orange or an apple. Its still a very small percentage.

If 10% of deaths are taking 15 years off of life then expectancy reduces about 1.5 years. (Super rough: .9*80.0 + .1*65 = 78.5)

Ah, i see what you mean.

Mary Lou Retton does not have health insurance and might die of pneumonia,

https://www.rawstory.com/olympic-gymnast-icon-mary-lou-retton-fighting-for-life-daughter/

Your comment actually highlights one of the inconvenient truths about the health insurance situation in the United States: it doesn't appear to contribute substantially to excess mortality in the United States (Retton is being treated, after all, as would nearly any person in the US brought to the ER with a life-threatening emergency).

None of that means, of course, we shouldn't adopt a rational, fully universal healthcare system along social democratic lines. We ought to, for a host of reasons beside the tiny increase in life expectancy we're likely to see.

In the US lack of access to healthcare IS contributing to excess mortality, it seems clear if you read the recent Washington Post articles on why US life expectancy is declining.

In the US lack of access to healthcare IS contributing to excess mortality,

As I acknowledged in the comment you're responding to, that contribution isn't literally zero. But it's not very substantial, at least in terms of affecting life expectancy; this is mainly because: 1) not having health insurances isn't literally synonymous with "people cannot get treated" (eg, Retton); 2) younger people (those who are uninsured) are generally pretty healthy; 3) even among sub-65 Americans, the vast majority of the population is insured (we're obviously now in the post ACA passage era. The one study most frequently cited, that by Harvard researchers in 2009, predates this); 4) Americans over 65 enjoy European-style single payer coverage.

Again, America should have a stronger safety net, and that includes truly universal, guaranteed health coverage for all. There are a number of reasons why such a move would be desirable. A substantial increase in life expectancy isn't one of those reasons.

Someone without health insurance will get emergency care until the facility can claim that it's no longer an emergency and then dumps the person on the street. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patient_dumping

This won't happen to Ms. Retton because she is famous and not poor.

People in the US are dying earlier due to lack of medical care for treatable illnesses. Our medical infrastructure is falling apart especially in states that refused to expand Medicare but also more slowly in states that did expand. Ordinary folks struggle to find primary care doctors and are still socked with co-pays and waits to get appointments.

This. For many folks, "preventive care" is an inaccessible joke.

Putting aside the difference in drug marketing, the "despair" deaths in the US seem to be tied to a lack of economic security, with those at the bottom rung bearing the brunt of the deaths.

In Europe, despite it also being affected by world economic trends, people do have a far better safety net making those economic downturns less catastrophic for individuals, which to me is likely to make them be less "despaired" (using the term to encompass both the mental and physical problems that people face as a result of economic need) than their American counterparts.

" This increase is not happening in European countries that have not only been buffeted by the same broad economic trends as the United States, but are also seeing the rise of right-populist backlash politics."

The European " right-populist backlash politics" are not led by somebody that wants to destroy democracy and replace it by a dictatorship based on the Putin/Xi/Kim model. This comparison is just nonsense.

Excellent point. We are now eight years and a couple of months since Trump has been leading one of our two major political parties. That is a uniquely American phenomenon. Don't pretend we and Europeans are all the same.

Summer of 2015 was when Trump first surged in the polls. That eerily matches the sharp upturn in overdose deaths for non-college-grads in the second of Kevin's charts above.

What happened then? It wasn't a big sudden change in pharma marketing (the Yglesias theory). The rise of Trump coincides with the surge in OD deaths. Draw your own conclusion.

(The Case and Deaton paper came out in 2015, and their analysis was drawing on previous data.)

OD deaths should be attributed to the illegalizatuon of drugs rather than on the drugs themselves. When users of these medicines do not know the quality or dosage overdose is a result.

The point of the Case-Deaton article was that in certain areas of the United States, white men of a certain age had a much higher death rate than would otherwise be expected. It was a combination of insults: smoking, obesity, alcohol, other drugs. If you look at your own graph, the divergence started growing around 2000, even before the Great Recession and the opiate crisis.

Yglesias makes some rather facile arguments here. He argues that it was only opiates, though the death rate highlighted in the paper involved numerous factors. Opiates did increase the death rate, but there is no argument that it was the only cause and could be the only cause. He argues that this hasn't happened in Europe which is rather off target given that Europe has a much different political system, geography, ethnography and safety net. He argues that the difference has to do with education levels, though education levels are as much a symptom as a cause.

I know Yglesias likes to do the old switcheroo. Water runs uphill, and he can prove it. Unfortunately, his critique seems to ignore the thesis of the paper he is criticizing. Yglesias is very hard to take seriously.

+1

"Yglesias makes some rather facile arguments here. He argues that it was only opiates, though the death rate highlighted in the paper involved numerous factors."

Exactly. E.g., drug OD death rates spiked more than rates for suicide and liver disease, but all showed significant increases. He never accounts for the other factors. He just dismisses them. Not sure if he's being facile or deceitful, but it's a fatal flaw to his analysis and conclusions.

"Yglesias is very hard to take seriously."

Yet too many people do. He has no special training or experience in the field but he writes in a pseudo-academic language that gets him attention with the fanboys (almost all boys) and earns him a living.

I have a question about Kevin's chart. He shows that there US high school dropouts fall behind other countries (and those who completed high school in the US). To know if this is US-dropout specific, though, I'd want to know how US dropouts compare to dropouts in other countries. Does anyone have that data?

Good question. The provided chart is likely misleading without this additional data for the other countries.

The connection between lack of formal education and opioid addiction should be pretty obvious. It's about having no other options when you get injured or your joints wear out. Men (esp.) without a HS diploma have very few employment options other than ones that involve pretty hard manual labor -- roofing, drywall installation, excavating, trucking, landscaping, etc. You get injured or sore and you can't work and then you're screwed. You almost certainly don't have benefits or insurance, so taking time off for surgery or PT is out of the question; you find a doctor or pharmacy to give you some pain meds and try to make the best of it. Pretty soon (thanks, Sacklers!) you're addicted and then life becomes about getting that next hit, legal or not (e.g. meth). Eventually you lose your job and then fentanyl comes along, which is dirt cheap and knocks you on your ass, but with every hit you do, you have a 50-50 chance of od-ing and dying, but you don't give a shit because your whole life has gone down the tubes by then. And there's your death of despair.

As others have pointed out, this doesn't happen in other countries (except shitholes like Russia) because workers have access to healthcare and therapy and other resources that amount to more than just writing them an rx for painkillers and sending them home.

Well said.

The use of painkillers does not always create addiction- in fact most often it does not. I've had such Rx for a shoulder injury, for surgery on a foot fraction and most recently for a succession of unpleasant oral surgeries after I fell off a ladder last year and smashed my mouth. Yet I'm not at all addicted to the meds-- I used them for a short time, then switched to ibuproffen and finally healed over enough I didn't need anything.

Well good for you. Read what I wrote, please. You obviously took pain killers after seeing a doctor who treated whatever issue you were having and only needed them for a short while because the underlying problem was fixed and you healed up. What causes addiction is taking painkillers over a long period to try to power through soreness or an injury that you *can't* get fixed because *you don't have insurance* and/or can't afford to take time off work for surgery and recovery.

My oral issues are ongoing.

The distinction is that I experience opioid pain meds in negative ways. One pill I can do, and yes, it fuzzes out the pain. But multiple pills over time leave me feeling ill and disturb my digestion. So once the pain diminishes I have no desire to continue taking the things.

Re: What causes addiction is taking painkillers over a long period

This is not quite correct. Long-term use leads to physical dependency, but that's not a synonym for addiction. Anyone who takes these sorts of meds long term will experience physical dependency-- but not everyone will become addicted. A friend of mine dealing with cancer took oxy for several months and yes he had nasty withdrawal symptoms when he tried to quit after his cancer was successfully treated. But he was motivated to do so and with medical help he was able to taper off the stuff and finally quit. The 64K question is why some people can do that-- overcome the physical dependency-- and some people lack the will to do so even if, in theory, they want to. I don't have any answers to that-- if someone can figure out it they should win the Nobel prize for medicine.

As others have pointed out, this doesn't happen in other countries (except shitholes like Russia) because workers have access to healthcare

100% of US workers have access to healthcare if we're talking ER-treatable emergencies, and about 90% of US healthcare workers have access to regularized healthcare (that is, they're insured).

If you let pharma companies drive profits by getting millions of people addicted to opiods—and then a cheap, super dangerous synthetic opioid hits the black market in great quantities—you're going to see a big spike in overdose deaths, especially relative to polities that maintained much more prudent control of opioids. The Occam's razor conclusion suggests this is a much more obvious and potent explanation than, say, a nine point "insured" differential. Indeed, this is especially true in light of the fact that not all of Europe looks like Denmark or Norway. Vast swaths of that continent (UK, Italy, Greece, etc) are characterized by substantial, post-industrial "despair" and a frayed safety net. And again, there are myriad statistical problems with the original study.

In 1990, a 73 year old high school dropout would have been ~17 in 1930. The high school graduation rate that year was 30%. A 63 year old would have been 17 when the graduation rate was 50%. A 53 year old would have been 17 when the graduation rate was 60%. In other words, in 1990 a significant proportion of HS dropouts were comprised of people who dropped out when dropping out was relatively normal behavior.

Over time, as people who dropped out in 1930 when dropping out was normal died out, the cohort of HS dropouts became more and more comprised of people who dropped out when finishing high school was the norm. In other words, there have been significant changes in the population of dropouts. In 1930, people who dropped out were doing something that most people did. We wouldn't expect to see much out of the ordinary with them. But in 1970, most people finished high school and not graduating was likely a sign of some other issue.