Paul Krugman has been getting a little more bearish on inflation, but he's worried about the latest employment news:

I have increasingly been turning to wages as a measure of underlying inflation. That’s not because I think greedy workers are driving inflation — they clearly aren’t. But wage growth is probably a pretty good indicator of how hot or cold the overall economy is running (and you can’t have a wage-price spiral without spiraling wages).

Unfortunately, this morning’s employment report was bad news on that front. Until this morning, it looked as if wages were slowing, but some of the old data have been revised up and the latest number was high. So a big decline in inflation may be a way off.

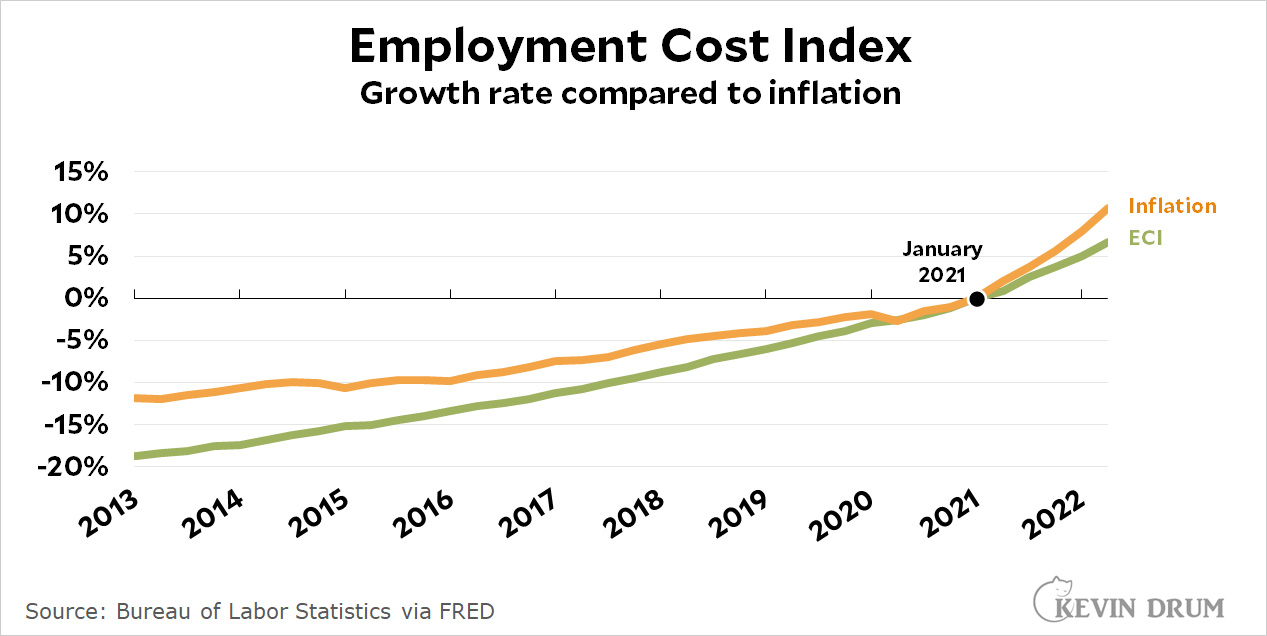

I don't really get this. Here is the Employment Cost Index through September:

Since the start of 2021 it's been rising less than the rate of inflation. I don't understand how overall compensation that's rising significantly less than inflation can indicate an overheated economy.

Since the start of 2021 it's been rising less than the rate of inflation. I don't understand how overall compensation that's rising significantly less than inflation can indicate an overheated economy.

Anecdotally, it does seem like I've seen more and more newspaper reports about wage contracts with eye-popping raises. There's no question that both employers and workers are well aware that inflation is eroding workers' earnings and they need to make up for it. Nonetheless, when you do the arithmetic it always turns out that the increases, though high in nominal terms, are still lower than inflation—or perhaps right at it. It's not like the 1970s, when union contracts routinely included COLA baselines plus increased pay above that.

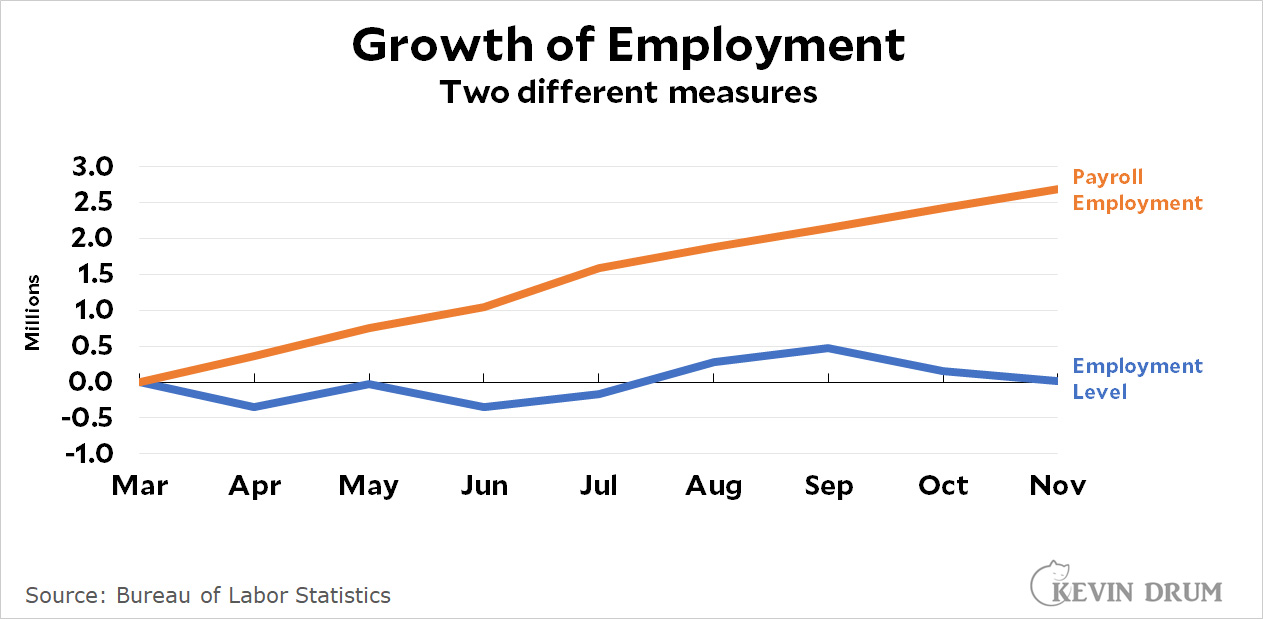

Of course, wages only accelerate if the labor market is tight, and I think it's an open question whether employment is even rising at the moment:

The other thing I don't understand is that Krugman, like everyone else, never seems to talk about lags. Surely it's worth mentioning that the numbers today, even if you'd like them to be even lower, are (a) declining, and (b) declining entirely on their own. The Fed's interest rate hikes haven't yet started to play a role.

The other thing I don't understand is that Krugman, like everyone else, never seems to talk about lags. Surely it's worth mentioning that the numbers today, even if you'd like them to be even lower, are (a) declining, and (b) declining entirely on their own. The Fed's interest rate hikes haven't yet started to play a role.

Oh, and while we're at it, I'd still like to know what everyone thinks the bedrock, underlying cause of inflation is. I'm not saying there isn't one. I just want to know what it is.

I don’t really care ‘what everyone thinks the bedrock, underlying cause of inflation is’ because those opinions will be uninformed. The can’t be otherwise, because our models of how the economy works are woefully inadequate. Consequently, opinions about the causes of inflation likely tell you more about the respondent’s politics than about the economy.

Yes, the causes of price increases for certain goods are apparent, are problems of reduced supply, not excess demand, and are one-off phenomena lacking mechanisms of positive feedback that would sustain an inflationary spiral. Price increases on widely used factors of production, like petroleum and natural gas, propagate through many other goods and services, but the sizes and time courses of these downstream effects don’t seem to be known.

Easy and easy job on-line from home. begin obtaining paid weekly quite $4k by simply doing this simple home job. I actually have created $4824 last week from this simple job. Its a simple and easy job to try to to and its earnings far better than regular workplace job. everyone (nhf-06) will currently get additional greenbacks on-line by simply open this link and follow directions to urge started.

Click On This Link———>>> https://salaryboost254.blogspot.com/

As a further point, seeking "the cause" for a monocausal explanation, when multiple factors are highly likely, is wrong-headed.

I’m happy to agree with Lounsbury, infrequent as such occurrences may be.

My cousin could truly receive money in their spare time on their laptop. their best friend had been doing this 4 only about 12 months and by now cleared the debt. in their mini mansion and bought a great Car.

That is what we do.. https://profitguru9.blogspot.com/

“Growth of Employment - Two different crappy measures”

The graph spans the traditional graduation months of May and June. If no new jobs were created in that period, then either unemployment would have increased, or the LFPR would have decreased. Did either of those things happen?

The numbers are seasonally adjusted to account for regular spikes or dips in employment that happen at certain times of the year.

Hadn’t thought of this before, but seasonal adjustments have to net to zero over the full year, otherwise error would accumulate….

Yes. We reduce job growth in November and december and May and June and increase it in January and February when construction and farming stops.

Embarrassing once again.

“I don't understand how overall compensation that's rising significantly less than inflation can indicate an overheated economy.”

Krugman’s point is that he is IGNORING CPI and using wage growth as a better measure of inflation. There’s no point in saying “look, your measure of inflation is less than my measure of inflation” - that doesn’t prove anything! It’d be like saying “well, PCE is lower than CPI, so the economy is not overheated.” It doesn’t even make sense!

You can disagree with Krugman about whether wage growth is a good measure of inflation, but you can’t just point out that it’s lower than CPI and then say QED.

“The Fed's interest rate hikes haven't yet started to play a role.”

This is obviously, embarrassingly false. They have not FINISHED playing a role - their effect will continue to be felt for a while yet - but to say they have not started playing a role is disqualifying.

I’m worried about you. You used to make sense.

If Krugman is actually “using wage growth as a better measure of inflation” I’d worry about Krugman.

The wage effect on the cost of goods or services is factored by productivity: dollars / hour of labor X hours of labor / unit output = dollars / unit

Per Krugman: "I have increasingly been turning to wages as a measure of underlying inflation." I think it's clear that's what he's doing.

As I said, "You can disagree with Krugman about whether wage growth is a good measure of inflation". Not sure I love it, either. But Kevin's argument was nonsensical.

For those of us whose grasp of the written language is a little shaky, 'a' != 'the'. Sure wish ligatures were more available.

Oh, well then, wage controls are the fix for inflation. No wage increases, no inflation!

Of course, Dr. Krugman has a Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne, and Dr. Schulz doesn’t. Krugman can still be wrong.

Agreed, on this subject Drum has become embarrassing and ungrounded, the very picture of motivated reasoning.

It seems generally unlike him.

his is obviously, embarrassingly false.

Why is it "obvious" that rates increases have, contra Kevin, begun to affect inflation? What's the causative mechanism?

For the record I'm skeptical of Kevin's take here, too, and my sense is tighter money has indeed already begun to work its magic; but admitedly I haven't done much reasearch, so it's more intuition at this point. Also, relatedly, Kevin seems to be insisting on a specifc time quantity of delayed action (12 months?) as absolute, unussailable dogma. Is he on firm ground here (is it unversally accepted that interest rate hikes require many months to be effective)?

The causitive mechanisms are the various transmission mechanisms that kick in immediately when a CB raises reference rate.

Of which, non-exhaustively

(1) variable rate contracts that are benchmarked on the reference rate rebase mechanically (enterprise and consumer, although there is a tendency here to think only via consumer and households, being blind to enterprise borrowing at variable);

(2) Financial institutions costs of funds typically direclty and indirectly benchmark off of CB reference rate and go up (immediately in some instances, delayed in others);

(3) Enterprise finance planning and investment spending at corporate (and generally SME ex-mom and pops who don't really plan), proper financial planning you look to your accelerating costs on funding typically immediately showing up in working capital at floating rates and lagging on other funding but contractually will occur (which are of course added on to other price pressures, many of which you're not yet passing through due to longer-term contracts, particularly on intermediate non-consumer-facing production), leading to reduced buying

This all ends up being demand destruction reduing pricing pressures.

Drum's assertions on timing are mechanistic and compelte over-readings of the econometric literate (or rather over-reading of whatever 2nd hand he has read). Rather similar to his bizarre insistance on monocausal explanation and his equally bizarre mischaracterisation of Fed or whomever preferred reference as some kind of rigid Either/Or (one can have a preferrred principal tracking metric but that is never the sole one and particularly where it is clearly [as since Covid] the economy is heavily distorted one does not rely on single metrics but typically one wants to have a basket taking look at leading as well as trailing given the messiness / fuzziness of near-term econometric data (that is your immediate data is known to be of uneven quality so important to balance and not over-read)

Of course for the inflation denialist wing of the Lefties and as well bizarro world Righties of the Libertarian world, if you want to look at non-intervention by CBs in face of inflation, one has cases like Turkey which has not taken action at all (even cut rates) and is experiencing the joys of hyperinflation.

Thanks.

I agree with Lounsbury.

The reason I say it's obvious is because it is extremely easy to see a very sharp slowdown in interest-rate-sensitive sectors of the economy. Housing is the obvious one, though I'd put tech in there as well. It seems quite obvious to me that these slow downs are (at least partly) caused by the Fed's rate hikes. To say that they "haven't yet started to play a role" simply flies in the face of the readily apparent evidence.

Kevin is correct that higher interest rates will continue to impact the economy after the Fed stops increasing rates; this is the famous "long and variable lag" between monetary actions and their effect on economic conditions. But he seems to have convinced himself that this means they don't START to affect the economy after a year, without any basis for this opinion. Look around! Higher interest rates are affecting (parts of) the economy already!

Kevin seems to be conflating his idea that there is a large (11-12 month) reporting lag and therefore the response to the Fed rate hikes isn't in the numbers with the idea that there hasn't been a response to the rate hikes in the real economy, which seems clearly false.

If wages are the problem (they aren't), has the Fed's actions caused their growth to crash? Obviously not. The rise in mortgage rates has definitely had an effect on housing prices, but how this will affect inflation is complicated. In the long run if investment in housing is slowed, this will put upward pressure on both house prices and rents.

I have one of those uninformed opinions and would appreciate an informed response by someone who knows better. Asked differently, perhaps the question is why we haven’t had much inflation until recently in a world awash with excess capital. Could it be that the massive decades-long shift in production to China and other low-wage economies kept price rises artificially low—in which case the answer to Kevin’s question is that this shift was disrupted (or even reversed) by the Covid shock?

"artifically low" is a judgment that does not make sense. There is nothing 'artificial' about China.

Prices lower due to developing economies joining supply chains and lower pricing particularly on lower-end consumer-facing goods? Yes.

Are supply chains to Asia in particular still disrupted due to Covid, yes although much less so than 2020 or 2021.

Would these disruptions feed through into inflation with lags as intermediate goods and intermediate services undergo price pressure and then eventually experience inflation, yes.

These lagging influences are clear inputs. Are they The Cause? (that is The Cause semi-irrationally sought by Drum, a monocausal thing like lead driving inflation and which is the wrong way to look at this) Not likely by themselves. Rather they are inputs into inflation pressure.

It is likely that multiple inputs - global fiscal stimuluses, supply chain disruptions, energy and food disruptions driving significant immediate price inflation converged (and some of those fed and feed into others for often significantly time-lagged feed through effects as pricing becomes unsustainable and then inscreases pass through intermediate goods and services, pricing in intermedaite goods often being sticky due to contracts, etc).

Fairly similar multi-year patterns are noticeable in the 1970s inflationary episode with pauses before re-accelerations. Thankfully Central Banks learned a lesson there

Employment costs rising faster than five percent annually are not a sign of slackening inflation. Inflation was outstripping employment cost increases for a few months in early 2021, but not anymore.

It's still a mystery to me why anyone thinks the Federal Reserve's interest rate target increases, which began in March and had been signaled by Fed officials back in December 2021, could not be affecting inflation yet. Interest rates matter.

Kevin seems to be citing this mantra as if it's something that's written in reputable textbooks. So I assume there's some basis to it. But, my sense is he's not correct to be so dogmatic on the duration of the lag he deems necessary. For one thing, the arrival of higher rates has an immediate impact on demand for dollars, thereby increasing their price (this doesn't take months, but mere days while making imports cheaper. Similarly, US exporters in some cases will start to see weaker orders almost immediately, which should very quickly begin to filiter into the demand they exert on the domestic economy (workers, energy, inputs and spare parts, office and industrial space, etc). Also, critically, pricier dollars should very quickly begain to impact energy markets, reducing one likey potent source of inlfationary pressures. And finally, dearer money impacts the real estate sector quite quickly. We've seen a dramatic cooling in only six months. It's hard to imagine this hasn't already begun go exert downward pressure on a lot of related sectors (lumber, furniture, white goods, mortgate lending etc). And we're now seeing nontrivial home value decreases, which historically makes people less confident about making major purchases (including cars), because they've become poorer. In short, the economy can cool very quickly, and, while it's not theoretically impossible for inflation to remain elevated when the economy weakens (stagflation) the absence of COLA contracts in the labor market suggest to broad economic cooling will, in fact, result in less inflation (and that seems to be what we're seeing).

A lot of good points there. Thank you.

+1

CPI has been at 2% to slightly above 2% since July.

I have to acknowledge that an article in Forbes did say, in January 2022, that Fed monetary moves typically have an effect spread out over time but with the largest effect taking more than two years to show up in inflation readings. Internet search is my friend, after all.

It's still not clear that no effect will be apparent in less than a year, and there was a Fed working paper from twenty years ago, which someone helpfully pointed to last week, that charted visible effects on personal income by the third quarter after a policy shift. I believe we're already there. I think Jerome Powell sees more moderate inflation coming, and that's why he's now telling the press that we might be done with rate increases now.

"It's still not clear that no effect will be apparent in less than a year," Fed was still engaged in quantitate easing through the first half of Mar 2022. So it has been less than 9 months since that they quit targeting deflation.

"which began in March and had been signaled by Fed officials back in December 2021" Fed was still engaged in quantitative easing though mid mar 2022. Actions speak louder than words.

For the Federal Reserve, words speak plenty loud. By the time actions were taken, no one was surprised. The policy shift had already been outlined.

My cousin could truly receive money in their spare time on their laptop. their best friend had been doing this 4 only about 12 months and by now cleared the debt. in their mini mansion and bought a great Car.

That is what we do.. https://profitguru9.blogspot.com/

Actually reading Krugman's column(*) Drum has focus on complaining about the inflation when the fundamentally more interesting subject is his real subject, the inflation target. Settling at 2% annualised ... or 3% or 4%.

Krugman is quite right, this is a moment to revise that almost accidental target number (2%), which is indeed too low as the almost decade and half since 2008 has shown amply. Part of our problems now with strange distortions (and probably policy that flowed more to Asset owners) came from 2% and that long period.

3 or 4 .... I suppose myself I might argue for 4 although maybe politically awkward.

As for lagging, really Drum, if you're asking this question it means that you really do not know the econometrics here and have a far, far too superficial understanding of the subject - and are in the zone of MAGAs unskewing polls.

(*: and Drum should take a hint, if he's disagreeing with Krugman on a macroeconomic matter, then its almost certainly his analysis and thinking that is wrong and not Krugman who is a very, very good macroeconomist.... the Lefties here love sniping at MAGA about ignoring expertise. Well...)

Yeah, I'd think twice about going against Paul Krugman.

I think the bedrock causes of inflation are fairly obvious:

* various disruptions due to Covid

* the war in Ukraine

* corporate price increases to further increase profits

Apropos of nothing, the spambots are really taking over all the comments sections here. Can nothing be done??

"Oh, and while we're at it, I'd still like to know what everyone thinks the bedrock, underlying cause of inflation is. I'm not saying there isn't one. I just want to know what it is." That's easy and has been widely covered.

1) The war in ukraine ha caused a massive dislocation in oil with asia getting oil at reduced cost and the west having to pay a premium

2) Global warming has cused systemic wide spread crop failures drving up the price of food.

3) All of the west's central banks went on a money printing spree as a result of covid causing real estate prices to massively rise. This is just now filtering down to rent which is about 1/3rd of the CPI index.

Only the third cause should be responded to by central banks. And the rate hikes that have already occurred should be adequate for this cause. Likely the fed should sell the bonds they accumulated from october 2021 to march 2022.

- illilillili: You left out peak oil. Really starting to increase costs of, well, nearly everything.

My cousin could truly receive money in their spare time on their laptop. their best friend had been doing this 4 only about 12 months and by now cleared the debt. in their mini mansion and bought a great Car.

That is what we do—————————➤

My cousin could truly receive money in their spare time on their laptop. their best friend had been doing this 4 only about 11 months and by now cleared the debt. in their mini mansion and bought a great Car.

That is what we do—————————➤ https://easyprofit24.netlify.app