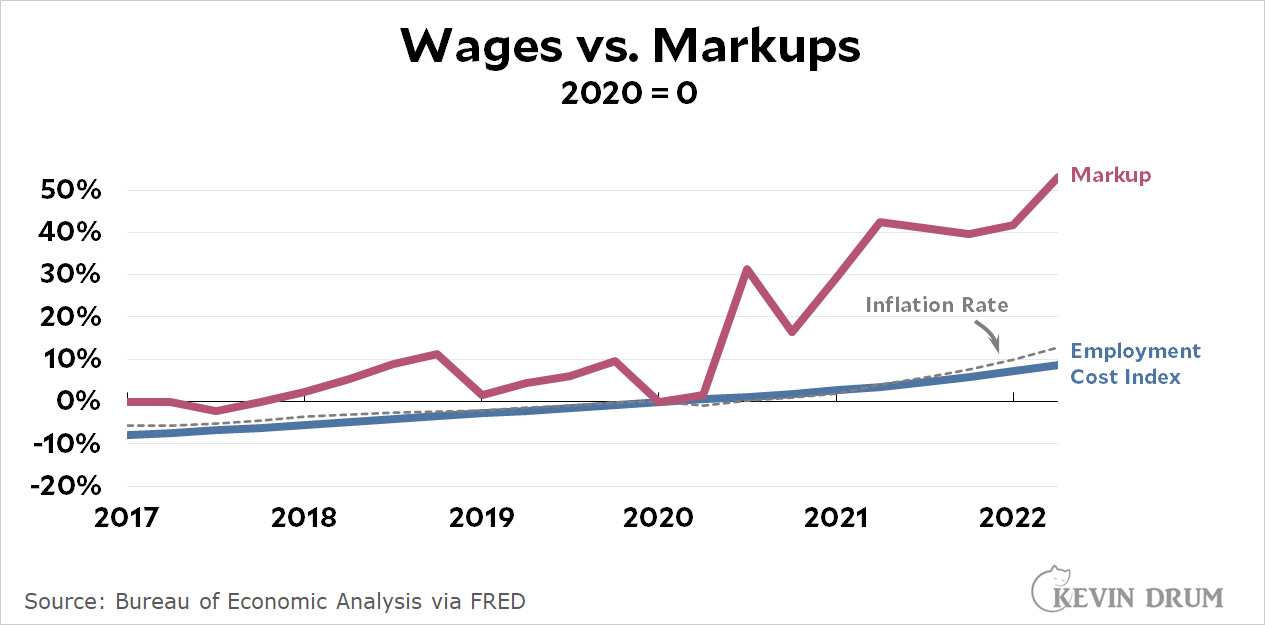

A couple of days ago I posted this chart showing that corporations were paying their workers less but marking up their products far, far beyond the rate of inflation:

But Matt Yglesias says there's nothing either wrong or unusual about this:

But Matt Yglesias says there's nothing either wrong or unusual about this:

Excess demand and profit-seeking by greedy corporations are not competing explanations for inflation — what happens when demand soars above productive capacity is that prices rise and profits go up. https://t.co/xckpVY14vl

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) November 2, 2022

This is a good point, but the problem is that it's very hard to prove. What we'd like to have is a good measure of demand, but we don't have one. None of us can peer into the minds of men and figure out how much they want to buy. Nor can we know at any given time how much future pain they're willing to endure in order to buy stuff now.

This means we have to look at metrics that are—we think—symptoms of demand rising above supply. In the case of food and oil, it's fairly easy to see that shortages—natural ones in the case of food, manufactured ones in the case of oil—have pushed supply below demand and that consumers are mostly willing to pay more until supply and demand are once again in equilibrium.

But for other things it's not so easy. Is there really a shortage of Pepsi, for example? Is it true that PepsiCo can't easily increase production? I have my doubts, but I can't prove anything.

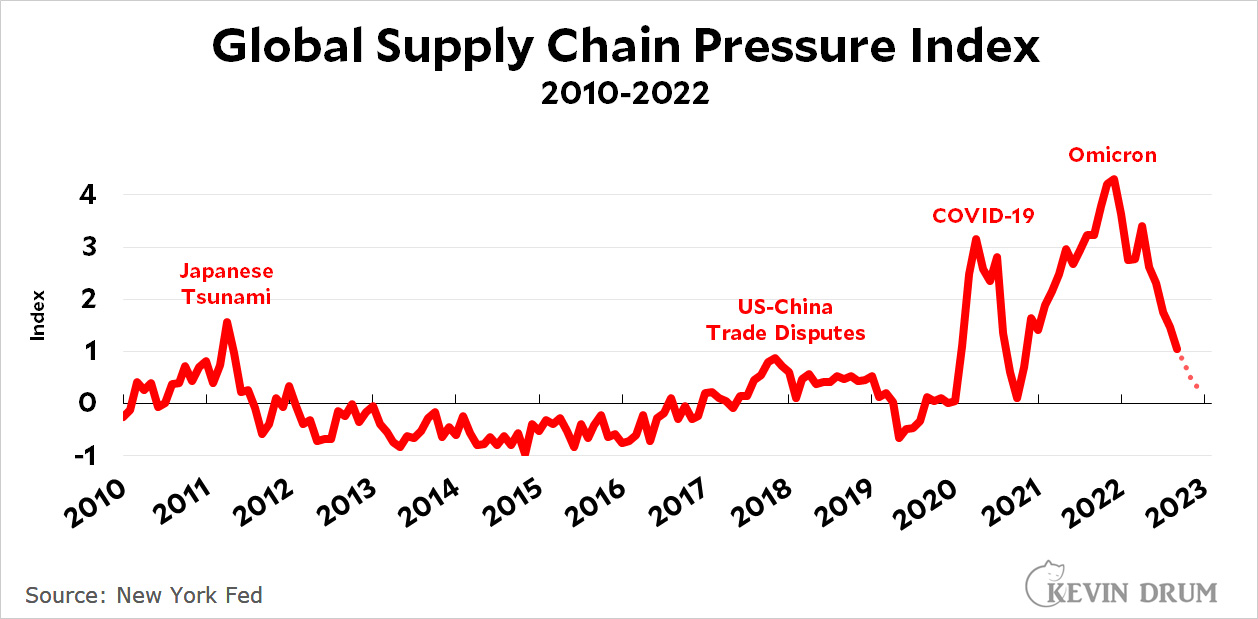

More generally, though, we can look at various metrics and draw some conclusions. For example, the Fed says that supply chain pressures have mostly gone away:

Other metrics tell us that earnings are down, savings are being used up, and the money supply is dropping. Put all this together and it suggests that supply has recovered to normal and demand is probably back to its pre-pandemic normal as well.

Other metrics tell us that earnings are down, savings are being used up, and the money supply is dropping. Put all this together and it suggests that supply has recovered to normal and demand is probably back to its pre-pandemic normal as well.

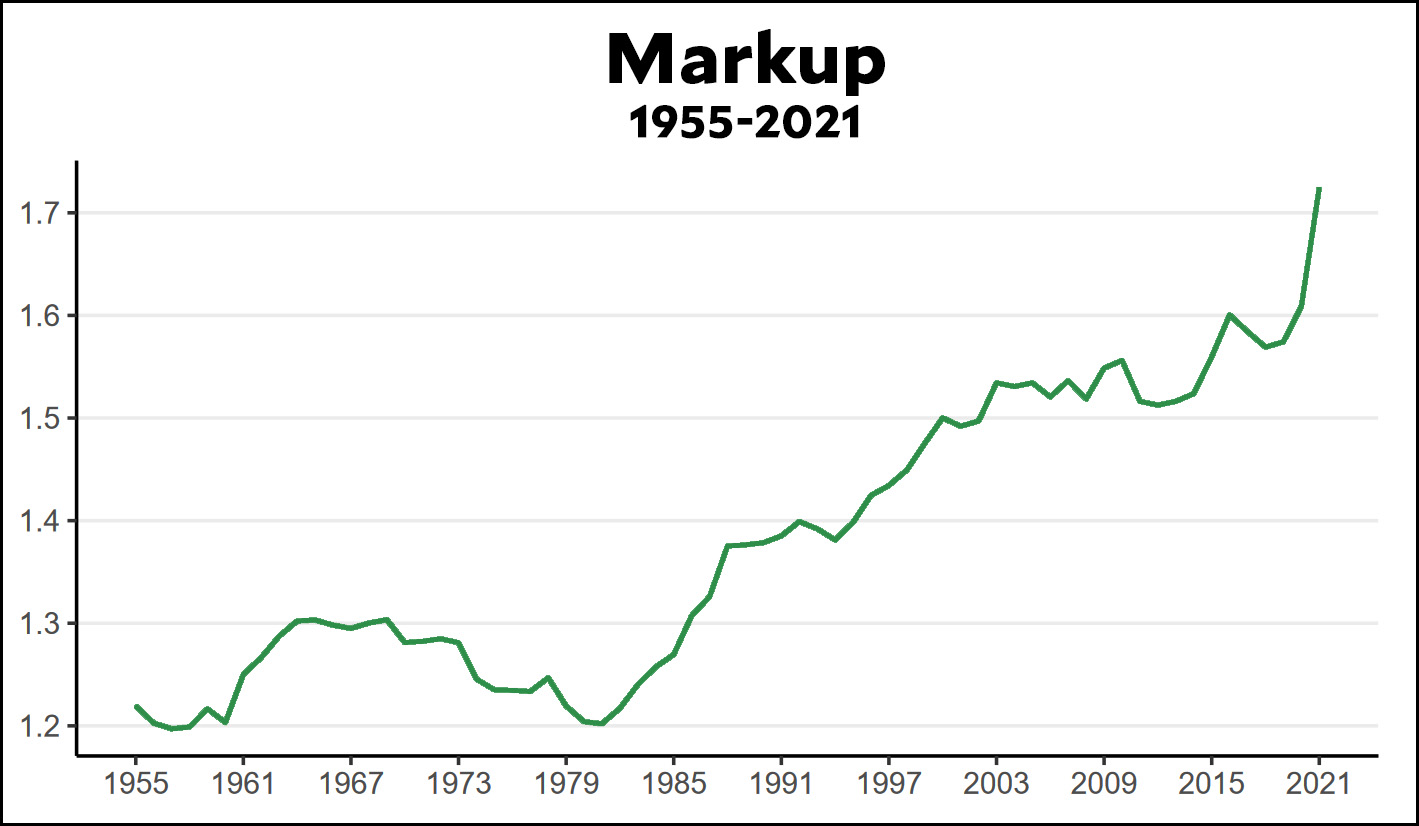

The other thing to consider is the huge size of the rise in markups. Markups generally go up after recessions, but markups today are higher than they've ever been since we started keeping records. Here's a different calculation of markups over the long term from the Roosevelt Institute:

The Roosevelt figures suggest that the rise in markups is less than the BEA numbers show, but the increase is still steep and the absolute level is higher than it's ever been. This suggests, once again, that companies are raising prices more than usual and more than they're being forced to by inflation.

The Roosevelt figures suggest that the rise in markups is less than the BEA numbers show, but the increase is still steep and the absolute level is higher than it's ever been. This suggests, once again, that companies are raising prices more than usual and more than they're being forced to by inflation.

Bottom line: Matt's point is a good one, but I'm not sure the evidence suggests that supply is in bad shape anymore or that demand is really a lot higher either. Company greed might be less than I thought it was, but it's still responsible for a fair chunk of our current inflation.

What seems to be missing here is a distinction between transient and steady states, We are clearly in a trasient state brought about by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. And in the transient state corporations are taking advantage of the mismatch between demand and production capacity, When the two come into balance, we will have a new steady state with fewer opportunities for corporations to mark up prices beyond reasonable rates.

Matt forgets, or maybe ignores (I have no way to prove it), that in his cool, savvy analysis there is suffering.

Incorrect. Historically he cares far more about Chinese suffering than American suffering.

It would be helpful if a media organization, someone like Mother Jones, published the information on what specific corporations are raising prices more than inflation. There is a lack of competition in some markets. But in the markets where corporations face competition, greater price transparency would help consumers make informed decisions and reduce inflation.

It's the job market that tells the story. There are far more openings than job seekers right now. Companies look to hire people because they think they can be employed to make more stuff that can be sold. But they are having trouble doing that.

What is happening is on the demand side, not the supply side, where you are looking. Even as people are complaining about inflation, they are buying lots of stuff. Stuff they probably held off buying over the last two years. There are signs of this everywhere I look.

I think that this is the problem we hoped for. This is a much better problem to have than another Great Recession, which was always a possibility with covid. This is the problem we worked for, too. We did a few rounds of stimulus spending. It worked. And now we are here, where jobs are plentiful, but seats at your favorite restaurant aren't.

You mean they have trouble doing that at the wages they are offering. Which tells exactly the opposite story. Thanks for bringing this to the collective's attention.

Yes, what you say is accurate. And I think it's noteworthy that they didn't have this issue a year ago. There is upward wage pressure, and employers are slow to adapt. This is Keynes' "sticky wages".

But the reluctance you highlight isn't the cause of the situation, it's an outcome of the situation we get when there is a surge in demand.

You misunderstand; I'm saying that if the situation was really an increase in demand relative to supply, then you would see wages increasing (this has been going on for -- what? -- the better part of a year now?) So by the contrapositive, no increase in wages implies no increase in demand. IOW, I'm not saying this is a driver; I'm saying this is a signal.

It's not clear if you are talking demand for workers or demand for products. There can be demand for products and companies unwilling to increase supply because the producer doesn't think the increased emend will be maintained long enough to recoup fixed costs.

Fed should make clear that rising profit margins are spurring inflation:

https://www.ft.com/content/837c3863-fc15-476c-841d-340c623565ae

Given the timing of the long-term markup rise, it's obvious what happened: the end of real antitrust enforcement in the Reagan era and resulting reduction in competition caused this. Time to bust some trusts! Bring back real competition!

As usual, Yglesias provides the most simplistic answer to a complex question and declines to think about it any further. He should be deeply and thoroughly ignored.

As usual, Yglesias doesn't bother to offer a way to test his hypothesis. His refusal to put his opinion to the test is something of a hallmark, and one of the reasons he should, as you say, be ignored.

Matt Yglesias simply assumes the conclusions, doesn't he?

If we assume that the US and world demand have soared above the possible production capacity and assume there is no loosely coordinated effort to withhold capacity....then you can't blame corporations, instead we blame the invisible hand and MARKETS!!??

Lol, assume away the problem!

A number of things have to be in place. There's been a lot of market consolidation and moves to "just in time...". Market consolidation means there's fewer choices for consumers--so switching brands when one raises prices can mean the same company gets the money--and that company can raise prices all around. The other thing that happens is that the major competitors meet the price rise--and the small ones do too because they could not ever meet the rise in demand due to the price hikes by the big guys. It's a vicious cycle, just not the wage-price one.

It helps to have something/one to blame for the price increases. It helps if the company doesn't get "blamed" for price gouging. Now somehow it's Biden's fault.

Some of this is due to Trump's tax cuts and asset inflation--which is not coming home to roost--but Biden is stuck with the blame....

If prices are marked up on non-essential items and sales remain strong, that's probably the strongest evidence possible that demand is high.

Do you have data to cite? Most of the price increases in the news have been in food and energy; not discretionary for most Americans, and not easy to substitute for.

One thing that I don’t see here is the concept of “elasticity” of demand or supply. Something we got a lot of when I was learning economics back in the early 70s.

Demand for gasoline is difficult to change in the short term – thus, it is inelastic.

It takes a while to change, in driving (and driving planning) habits, changing to more fuel efficient cars, alternate transport, etc. Very demand inelastic.

That’s also an opportunity for companies to greatly increase their markups – and blame it on “inflation” – which they mostly created out of whole cloth. Much more profitable that trying to hire more workers, get in better production equipment.

There is also inelasticity in supply – it can be hard to get good people out to where they are needed in the short term. Still hard to get equipment – especially if you didn’t bother to plan very well. So, why bother – gouge away.

The TX main local grid pricing plan is an excellent example of exploitation of anelasticities to create huge profits in a crisis.

"Is there really a shortage of Pepsi, for example? Is it true that PepsiCo can't easily increase production?"

Since the pandemic began, Pepsi Max has been in short supply. When I go to any one of the multiple supermarket chains around me, it's a crapshoot as to whether it will be there or not. But when it is available, it's at the sort of price I expect (modulo the usual week to week discounts for buying four 6-packs, or 5 2L bottle or whatever).

Which pretty much proves Yglesias' point. If you were trying to price gouge on Pepsi, this is an extremely dumb way to do it -- making it frequently unavailable, and not any more expensive when it is available.

As to why PepsiCo can't increase production, who knows? The critical ingredient is some chemical from a factory in China that had covid labor issues? The situation now is much better than 2020/2021, but I'd still not call it "fully functional".

So no, there isn't a shortage of Pepsi. And yes, given that people absolutely hate it, I'm not at all surprised that Pepsi Max is in 'short supply', i.e., not worth dedicating shelf space on the poduct.

"This suggests, once again, that companies are raising prices more than usual and more than they're being forced to by inflation." This isn't necessarily true. Different industries have different historical markup rates. What is at least partly happening is that those industries with higher historical markups are grabbing a larger share of the economy and those with lower historical markups are grabbing a lower share of the economy. Older industries traditional have small markups. new industries have large markups. Though where I live, you are definitely seeing grocery stores, traditionally low markups, substantially increasing their profit margins as well.