Test your knowledge:

Q: How long does it take the FDA to approve new drugs?

A: About seven or eight months on average.

No, no, wait. It takes years. Everyone says it takes years. What nonsense is this?

It's not nonsense. Once a New Drug Application is submitted, the FDA typically turns it around in a few months. What's more, studies have repeatedly shown that the FDA is generally faster than European, Canadian, and most other regulatory agencies around the world. They also approve more drugs than the other agencies.

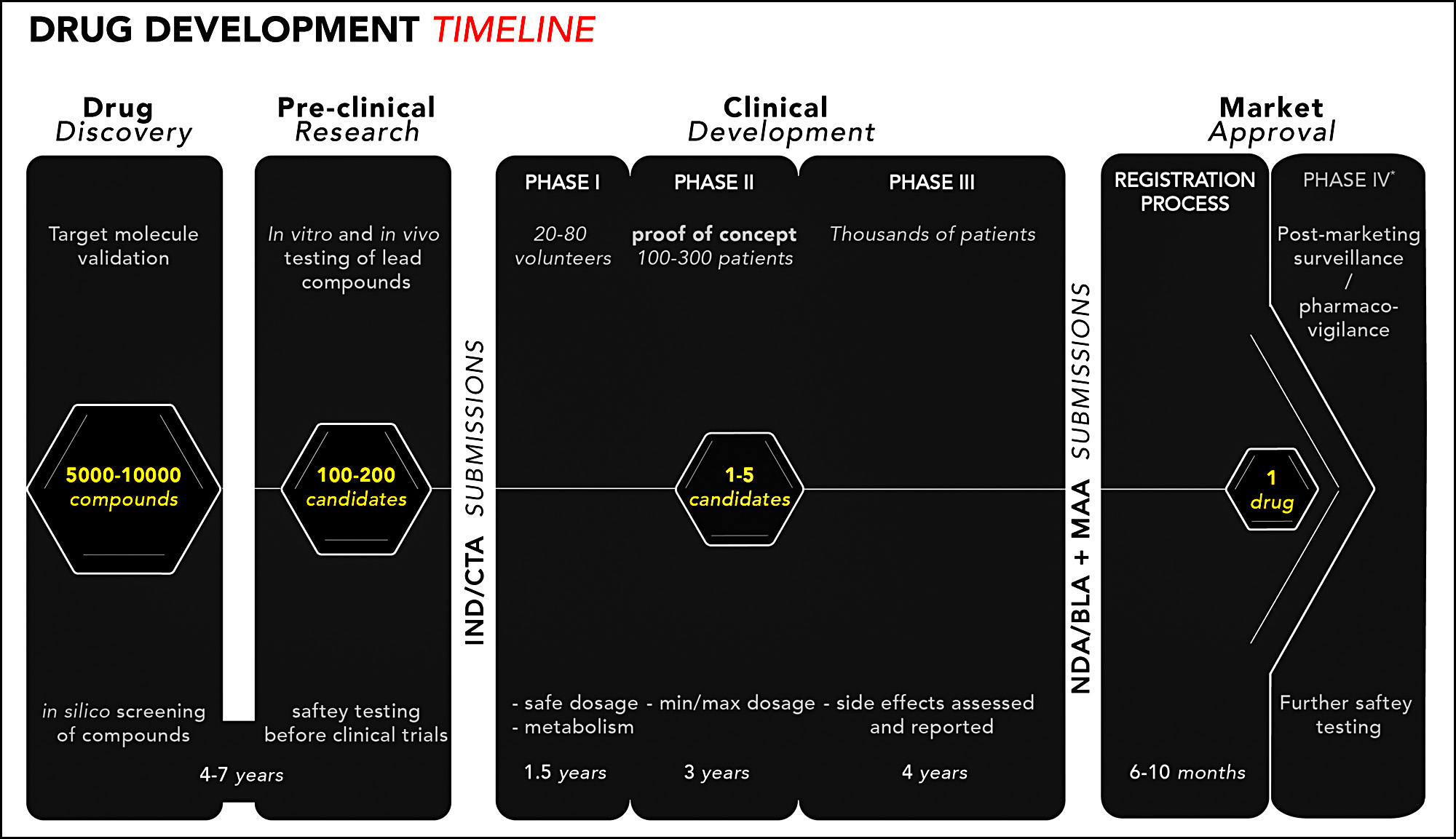

What does take a long time is clinical trials. The entire process of discovery and testing of new molecules takes anywhere from 10-15 years:

So if you want to speed up new drug approvals, the place to focus is not the relatively short final stage but the tortuous clinical trial stage. Here's an estimate of how many drugs make it through the various development steps:

So if you want to speed up new drug approvals, the place to focus is not the relatively short final stage but the tortuous clinical trial stage. Here's an estimate of how many drugs make it through the various development steps:

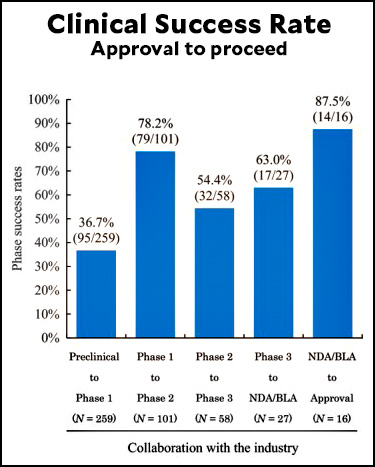

Lots of people complain about the FDA being too slow, and in some cases there's something to this.¹ But the FDA is careful for a reason: although you may not hear about it a lot, most drugs are failures. As the chart above shows, fewer than 10% of all candidate drugs end up making it through the entire gauntlet. The rest either don't work or turn out to be unsafe. The only reason we know this is because the testing regimen is so strict.

Lots of people complain about the FDA being too slow, and in some cases there's something to this.¹ But the FDA is careful for a reason: although you may not hear about it a lot, most drugs are failures. As the chart above shows, fewer than 10% of all candidate drugs end up making it through the entire gauntlet. The rest either don't work or turn out to be unsafe. The only reason we know this is because the testing regimen is so strict.

But there's one stage where almost everything makes it through: Phase 1 trials. This prompts me to wonder why we bother with it. Why not combine Phase 1 and Phase 2 and cut a couple of years out of the whole cycle?

I'm sure there's a good reason not to do this, but I can't figure out what it might be. I suppose that's because the answer is so obvious that no one ever bothers asking the question. But I'm asking. Why bother with a step that almost never uncovers serious problems?

¹This is probably more true for medical devices than drugs, but there are certainly cases of drugs that have taken longer to approve than they should have.

UPDATE: The answer appears to be pretty simple. Phase 1 trials are done on healthy volunteers to check for safety. Only if healthy patients can tolerate the drug is it given to sick people in the Phase 2 trial.

Often Phase 1 and 2 are combined. They'll do a dosing study hoping for efficacy. Other times the drug may be so new that strict Phase 1 studies are needed because the possible side effects are not well understood.

US Dollar 2,000 in a Single Online Day Due to its position, the United cx02 States offers a plethora of opportunities for those seeking employment. With so many options accessible, it might be difficult to know where to start. You may choose the ideal online housekeeping strategy with the help vz-81 of this post.

Begin here>>>>>>>>>>>>>> https://letswise099.blogspot.com/

Why isn't there a way to alert about spam LIKE THAT ONE or other kinds of unacceptable comments here (along with no thumbs up/down)?

By typical design, Phase I trials are safety trials in healthy people to determine the safe range of doses. So if 1 out of 5 trials fail here, that means that they were unsafe for the healthy population. If you skipped this trial and went directly to testing in people with an underlying disease (where they would be expected to be more sensitive to toxicity due to physical harm from the disease) you could end up with a lot of severe/dangerous side-effects.

yes. na ga ha pa.

Taking the COVID experience into account, it appears Phase III could overlap Phase II and drugs could have an emergency authorization-type approval before Phase III is completed.

Take the mRNA vaccines approved on an experimental basis in 9 months. No healthy person under 50 should have taken a shot and they ended up causing a lot of severe injuries and deaths.

I realize that the left has a long history of not questioning pharmaceutical companies but this should change their minds.

Citation?

Facebook! Fox! Twitter! And the Maximum Leader Chosen By God!

Don't believe ANY of those "statistics" or "doctors" or any of that nonsense about "saving lives!" Those are the LIES of SATAN! And DEMOCRATS! Like FAUCI!!

He doesn't have one. The defining trait of anti-vaxxers is that they will believe absolutely anything as long as it is not supported by evidence.

"Danish professor: mRNA vaccine study sends 'danger signals'" on YouTube. (UnHerd podcast)

Her research group had a paper published in May 2022 showed those under 50 should not get an mRNA shot because the health risks were higher than the potential benefit.

Ah, Youtube, the source of reliable medical information. Whose your leech guy?

Not meant as support for roboto's assertion(s), and disregarding the ick factor, leeches do have a place in modern medicine: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hirudo_medicinalis#Current among other hits for "leeches in medicine" ...

You wouldn't have understood a single word the Danish professor was saying about the risks of taking mRNA shots.

Well, cite the paper. The only study by Christine Stabell-Benn that Google Scholar turned up for me was a preprint from December 2023, not 2022.

“ Stabell-Benn is keen to stress that the sample is relatively small and is calling for further investigation, and also that the study took place during very low levels of Covid, so the relative advantage of protection against Covid would have been smaller at that time compared to at other points in the pandemic.”

https://unherd.com/newsroom/study-into-mrna/

The link has, within its text, a link to the paper.

Prof. Stabell-Benn: "I have been in this game for now almost thirty years, studying vaccines and finding these non-specific effects which have been very controversial. There are strong powers out there that don’t really want to hear about them."

This paper is why some European governments stopped giving those under 50 year olds boosters from late 2022, with rare exceptions, and for the past year most European governments do not give shots to those under 60 or 65, with rare exceptions.

This is a lie. As one example, in France they merely relaxed their recommendations for who NEEDS to get one, not who CAN get one. Anyone can get one if you want it. And of note, they recommend pregnant ALL women get them, which kind of negates your idiotic point that it's considered dangerous to younger people and refused to them. Your brain is rotted and filled with worms.

https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/p_3417408/fr/covid-19-la-has-publie-sa-recommandation-de-strategie-vaccinale-pour-2023

Your French sucks.

I wrote that she advised no healthy person under 50 should take the shot. Your English sucks too: look up the word "exceptions."

Liar. You said most European governments won't even give you shots under 50 "with rare exceptions"

Being pregnant under 50 is not rare, nor are they refusing to give anyone at all shots if they want them, you ignorant fuckweasel.

A description of a YouTube video is not a citation, you ignorant dipshit.

I assumed you were familiar with the internet. Fortunately, a good Samaritan was able to guide you.

How could 95 "pass" Preclinical to Phase 1, but 101 enter Phase 1 to Phase 2?

Related, how/why would 79 pass Phase 1 to Phase 2, but only 58 enter Phase 2 to Phase 3, or 32 pass Phase 2 to Phase 3 and only 27 enter Phase 3 to DNA/BLA?

I think it is a timing issue. At the start od=f the review there were different studies in each stage of the process so thenumbers going from one stage to the next do not have to match.

In which case:

Isn't quite as well supported as one might think.

It should be a reasonably good estimate, but with uncertainty due to the smaller n’s.

Drugs that work have very short development cycles. Phase 1 demonstrates safety, phase two some efficacy and phase 3 comparison with standard approaches. Really effective drugs are spotted early and have very short development to approval times. It’s the marginal drugs that take time and money. Interestingly the mot effective cost the most though their development costs are fewer.

Hi Cycledoc

Your last sentence

Interestingly the mot effective cost the most though their development costs are fewer.

Do you mean that the most effective have the highest PRICE - while COSTING the least to develop?

Phase I is safety, in very small and healthy populations, and a big reason for it is to keep candidate drugs that exhibit safety problems (eg toxic side-effects) in HEALTHY subjects from being given to MORE subjects with the condition(s) the drug is supposed to treat (which would be as bad or worse).

All of which is to say, it's a TERRIBLE idea, for medical / ethical reasons among others, despite any putative organizational-efficiency benefits. So, no.

Similar ideas that might / do help, and that have been in practice or under discussion for some time, are combined phase IIb/III trials, and the idea of "phased approval," where drugs could be approved for marketing in LIMITED populations sooner, the idea being that the additional risks incurred are more than offset by the benefits provided by making relatively advanced drugs available sooner to the populations that need them most. The latter would be VERY complicated, however -- as if the process isn't already complicated enough -- so it's not been widely adopted yet.

78% is “almost everything”?

When it supports his conclusion, of course!

Agree with bbleh regarding Phase 1 trials. My company runs a lot of them. They are essential and also pretty quick. In my experience, three things really slow down drug development: first, drug companies and clinical sites (i.e., the clinics and research hospitals that actually conduct the trials) can take FOREVER to set trials up (especially the "prestige" medical centers). They often move very slowly. What's more, to exaggerate only a bit, the process resembles manufacturing before mass production. Running a trial is a complex legal, business and ethical endeavor. There are a lot contracts, budgets, ethics reviews, bespoke databases, drug/placebo distribution systems (each trial has one) and a LOT of it is built from scratch with each trial. Expensive and SLOW. A lot of the players -- e.g., the third-party clinical trial management companies to which many pharma companies outsource trial management -- are, in effect, paid by the hour. Not much incentive for speed or innovation there. Second, if the disease being investigated is of great current interest, it can be hard to find patients to participate in your trial, because there are so many to choose from. So recruitment can take a long time -- years. Finally, investment required to develop a drug is so huge i (as is the potential return) that clinical studies are often designed to answer many more questions than they should, as a form of scientific risk reduction. Or, a development program may consist of way more studies than you'd think -- again to gather data that helps reduce risk as the drug candidate moves forward. That slows things down further. In any event, it ain't the FDA, which is pretty quick, despite having a huge workload, especially when the disease being investigated is dire and there are few or no treatment options. The Agency can move especially quickly then, as it should.

Those Phases are, presumably, required as pre-requisites of the FDA approval process, yes? If someone does not take their drug through them, they won't get to the approval step which takes seven to eight months. So sure, the final approval step may take less than a year, but one must go through [howevermany] years to even be allowed to take the final step.

Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 (there's also Phase 4, for studies done after a drug has FDA approval) aren't really "legal" terms. The law requires you to prove a drug is "safe and effective" for its intended use. The progression typically goes like this: First, preclinical work to see if a molecule holds promise. These are usually studies in cell cultures and animal models of the target disease. Second, short-term toxicology studies (again, in animals and cell cultures) to make sure it's safe to give healthy volunteers in Phase 1. Third, Phase 1, usually in healthy volunteers, usually a single-ascending dose and then a multiple-ascending dose study. The single dose study gives one set of volunteers a single, tiny dose. If there are no issues, the next group gets a slightly larger dose, and so on. If there are no issues, the next cohorts of volunteers get multiple days of drug -- once a day for two weeks, for example. Again, the first cohort gets a very small dose, the next cohort gets a bigger one, etc. If that all looks good, the developer picks a few doses and sets up one or more Phase 2 trials. These are in patients and the goal is to see if the drug is safe -- and one hopes, effective -- in people with the disease and to identify your likely "go for approval" dose. Unless the disease is very rare (or very bad and there are no treatments), the FDA usually requires two "well-controlled" Phase 3 studies. In addition to that, the FDA will not approve a drug unless the developer can show that its manufacture of the drug is up to standard and that a number of other studies (e.g., of interactions with other commonly prescribed drugs, long-term toxicology) have been completed and show no intolerable risks. These other studies are usually done in parallel with Phases 2 and 3 and don't slow down the approval process.

That being said, a developer can get very rapid approval of a drug that appears to help very sick patients with no other options. Many cancer drugs have been approved based on very small Phase 1b/2a studies (often with the developers commitment to complete a larger, confirmatory Phase 3 study).

Does the FDA have requirements about where Phase I trials happen? I have a new doctor who has prescribed a natural supplement. The research for its efficacy all seems to have taken place in Africa. I did not find it convincing -- small number of trials, mainly -- but it's obviously not a dangerous supplement, so I am trying it. This turns out to be the case for lots of supplements; they're tested overseas in low-regulatory environments where it's easy to sign up human subjects.

Supplements are not drugs - their efficacy does not have to be proven. If a company is selling something that has actually passed the efficacy tests - for which there are rules - they will probably call it a drug or medication, not a supplement.

Arming teachers, what could possibly go wrong?

Tennessee teacher arrested after bringing guns to preschool and threatening to shoot colleague,

https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/tennessee-teacher-arrested-bringing-guns-preschool-threatening-shoot-c-rcna148667

OK, but maybe not all that relevant to drug trials in the US.

It's a massive health experiment where the entire school age population are the guinea pigs.

There's a famous case from England 18 years ago. First test of a monoclonal antibody with 6 healthy volunteers caused an extreme reaction ("cytokine storm") within 90 minutes resulting in hospitalization. The drug showed problems in test animals. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theralizumab#History