On Wednesday I wrote a post saying we didn't have a housing shortage. I got a lot of pushback on that, so I figured I'd take a deeper look.

The result is a big pile of charts. Basically, it's everything I could think of related to housing with no cherry picking and no game playing. I just picked out everything I could think of that's an indicator of housing supply. Many of the data series go back only to to the year 2000, so I started them all off at 2000 to make sure of comparing the same time period for everything.

Some of you will undoubtedly have some issues with all this, but wait until the end before you go ballistic. After the charts are done I'll have a bit of discussion. Then you can go ballistic, OK?

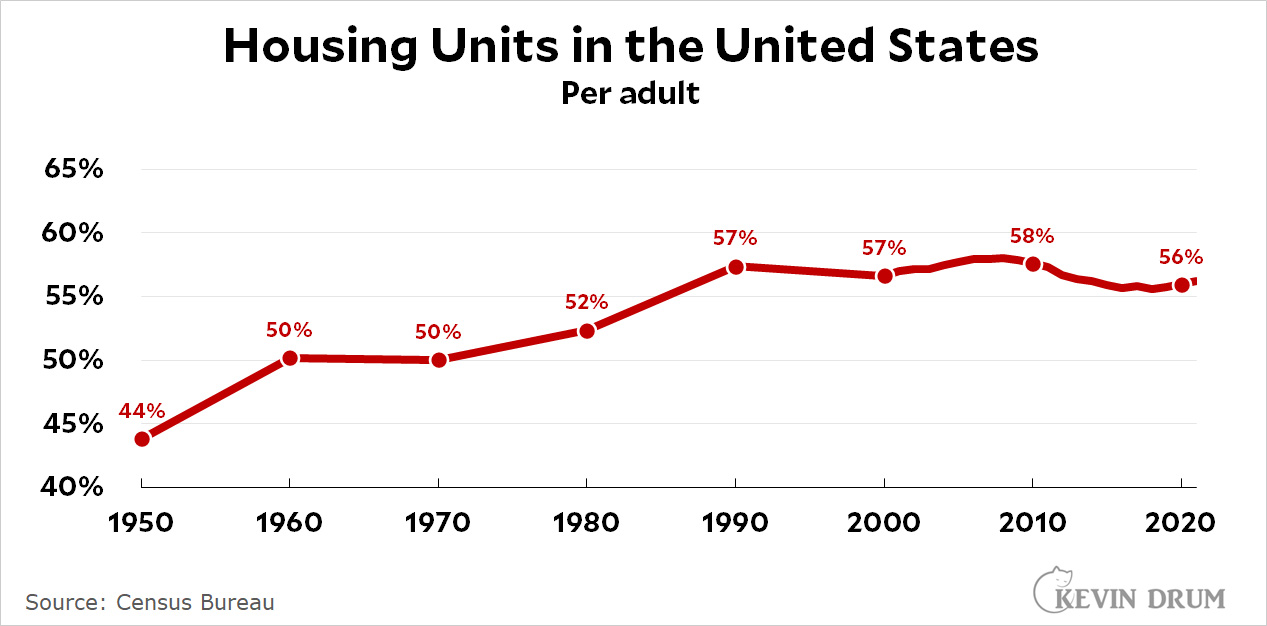

First up is growth of housing units vs. growth of adult population:

"Housing units" mostly includes single apartments and single-family homes, but it also includes everything else people live in: mobile homes, houseboats, or any single room intended for occupancy as separate living quarters.

"Housing units" mostly includes single apartments and single-family homes, but it also includes everything else people live in: mobile homes, houseboats, or any single room intended for occupancy as separate living quarters.

I charted this over a long period in order to provide some context. After World War II there was a huge shortage of housing as soldiers returned home and got married. It was a major political issue that produced housing developments like Levittown; the growth of suburbs and interstate highways; and a huge increase in housing projects for low-income families.

The result was strong growth in housing units, followed by another strong growth in the '70s and '80s as the baby boomer generation grew up and moved out. More recently, growth slowed down: In 2021 the number of adults barely budged, ending at 252.6 million. The number of housing units ended up at 142 million, for a ratio of 56.2% (compared to 56.6% in 2000).

You can draw your own conclusions from this. On the one hand, housing growth has slowed down considerably. On the other hand, this was largely because population growth also slowed down considerably. On a countrywide basis, we have the same number of housing units available per adult as we did 20 years ago.

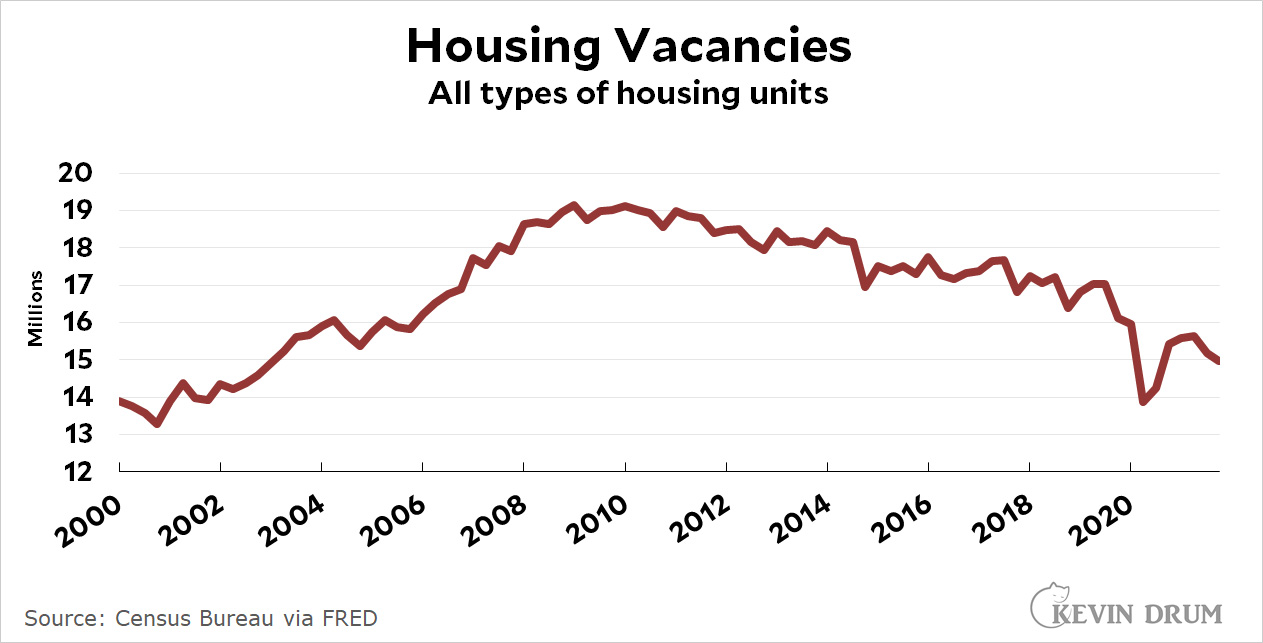

The next chart shows housing vacancies:

Ever since the housing bust in 2010, the number of housing vacancies has gone down. This is to be expected given the substantial overbuilding during the housing boom of the early aughts. Overall, the current decline suggests a tightening of the housing market, but only to the level of about 2005 or so.

Ever since the housing bust in 2010, the number of housing vacancies has gone down. This is to be expected given the substantial overbuilding during the housing boom of the early aughts. Overall, the current decline suggests a tightening of the housing market, but only to the level of about 2005 or so.

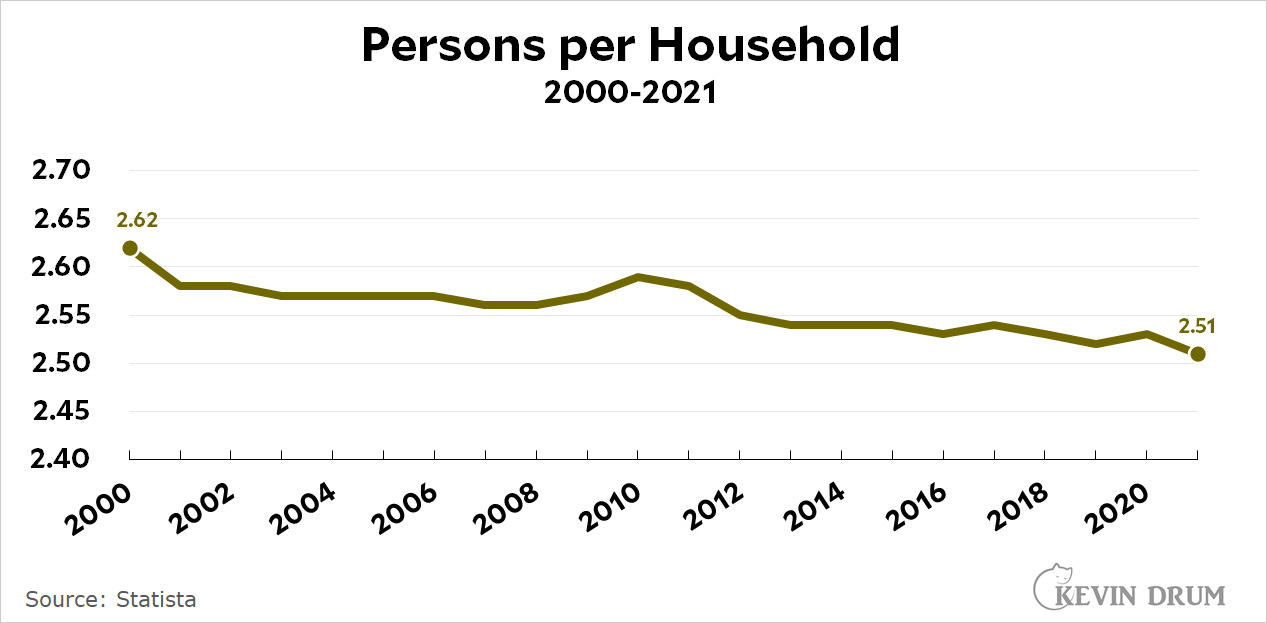

Here is household size:

If there were a shortage of housing you'd expect to see more crowding. However, since 2000 the number of persons per household—i.e., the number of persons per housing unit—has gone down. There's less crowding now than there was 20 years ago.

If there were a shortage of housing you'd expect to see more crowding. However, since 2000 the number of persons per household—i.e., the number of persons per housing unit—has gone down. There's less crowding now than there was 20 years ago.

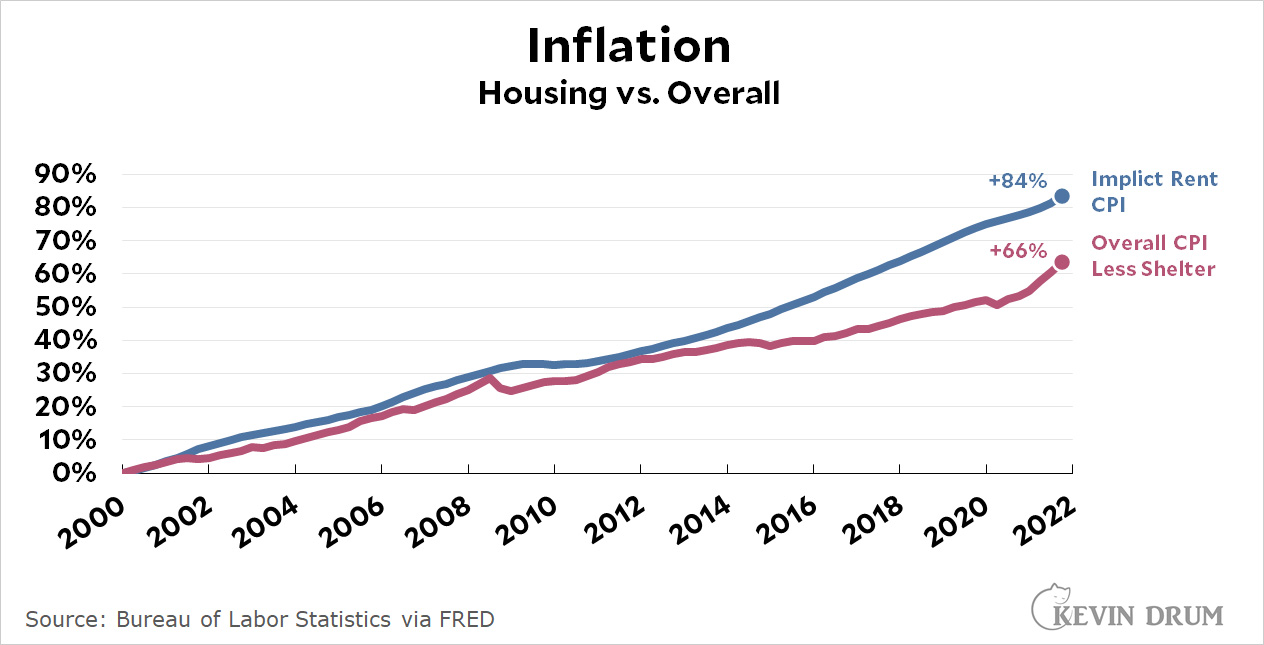

Now let's take a look at housing costs. Here is housing inflation vs. overall inflation:

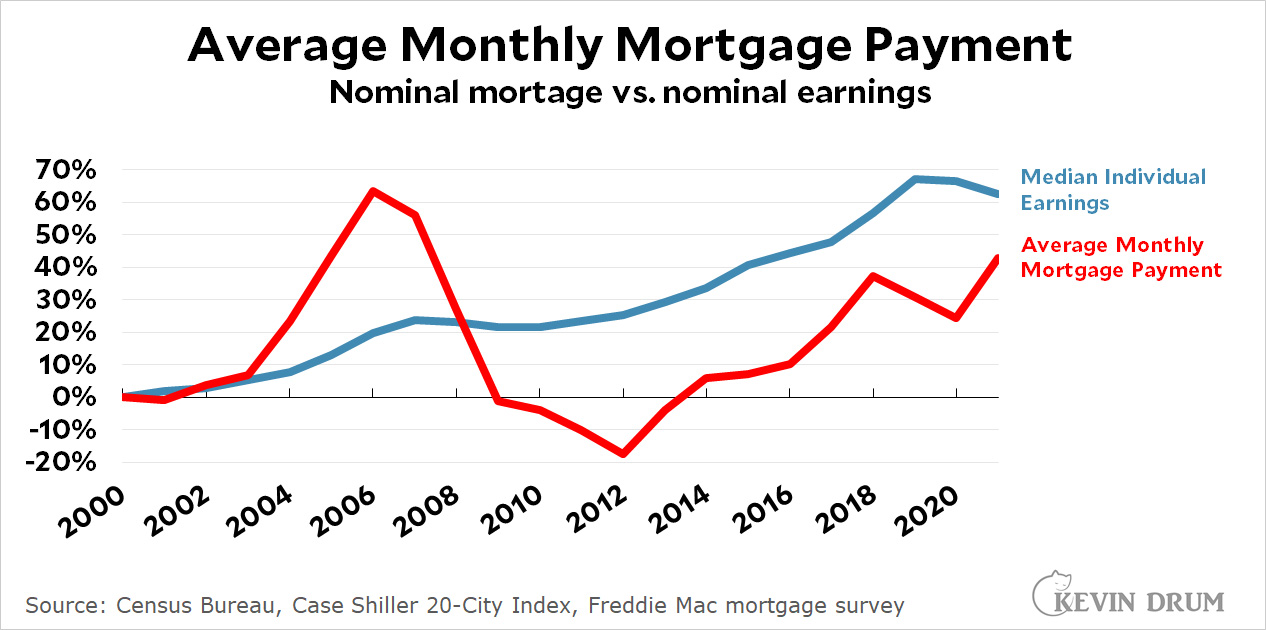

Rent has grown 11% more than overall CPI since 2000 (184 ÷ 166 = +11%). This suggests a tightening of the housing market—the rental market in particular—but note that it's a measure of inflation, not prices directly. The next two charts do that. First up is the average monthly payment for a single-family home compared to average earnings:

Rent has grown 11% more than overall CPI since 2000 (184 ÷ 166 = +11%). This suggests a tightening of the housing market—the rental market in particular—but note that it's a measure of inflation, not prices directly. The next two charts do that. First up is the average monthly payment for a single-family home compared to average earnings:

The price of homes has risen considerably since 2000, but mortgage interest rates have fallen considerably. On average, a family's monthly mortgage payment today is a smaller percentage of their income than it was in 2000.

The price of homes has risen considerably since 2000, but mortgage interest rates have fallen considerably. On average, a family's monthly mortgage payment today is a smaller percentage of their income than it was in 2000.

The story is slightly different for rental housing:

In an effort to be fair, this chart compares median rent to the median income of the 40th percentile. This is probably more representative of the income of renters than overall median income. As you can see, rent has stayed pretty steady at around 24% of income, with only small changes from year to year. Overall, there's little indication that rents have skyrocketed over the past couple of decades.

In an effort to be fair, this chart compares median rent to the median income of the 40th percentile. This is probably more representative of the income of renters than overall median income. As you can see, rent has stayed pretty steady at around 24% of income, with only small changes from year to year. Overall, there's little indication that rents have skyrocketed over the past couple of decades.

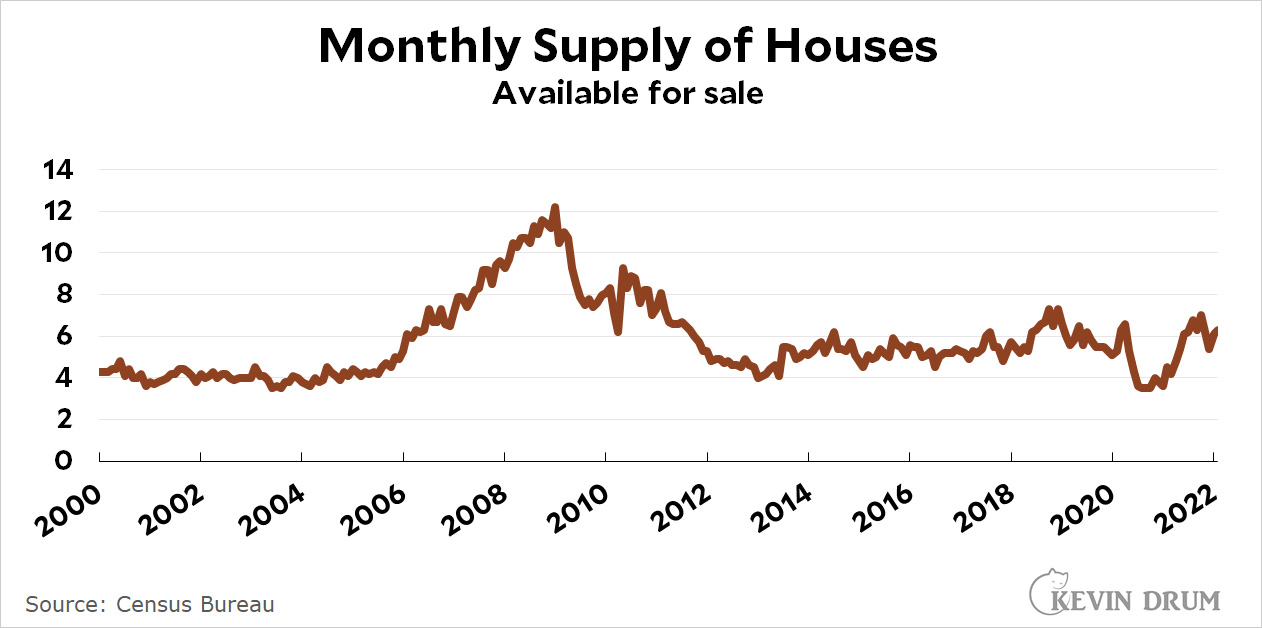

Here's the monthly supply of houses available for sale:

There's nothing much to see here. Housing supply has been pretty flat since 2013, and it's been flat at a slighly higher level than it was in the early aughts.

There's nothing much to see here. Housing supply has been pretty flat since 2013, and it's been flat at a slighly higher level than it was in the early aughts.

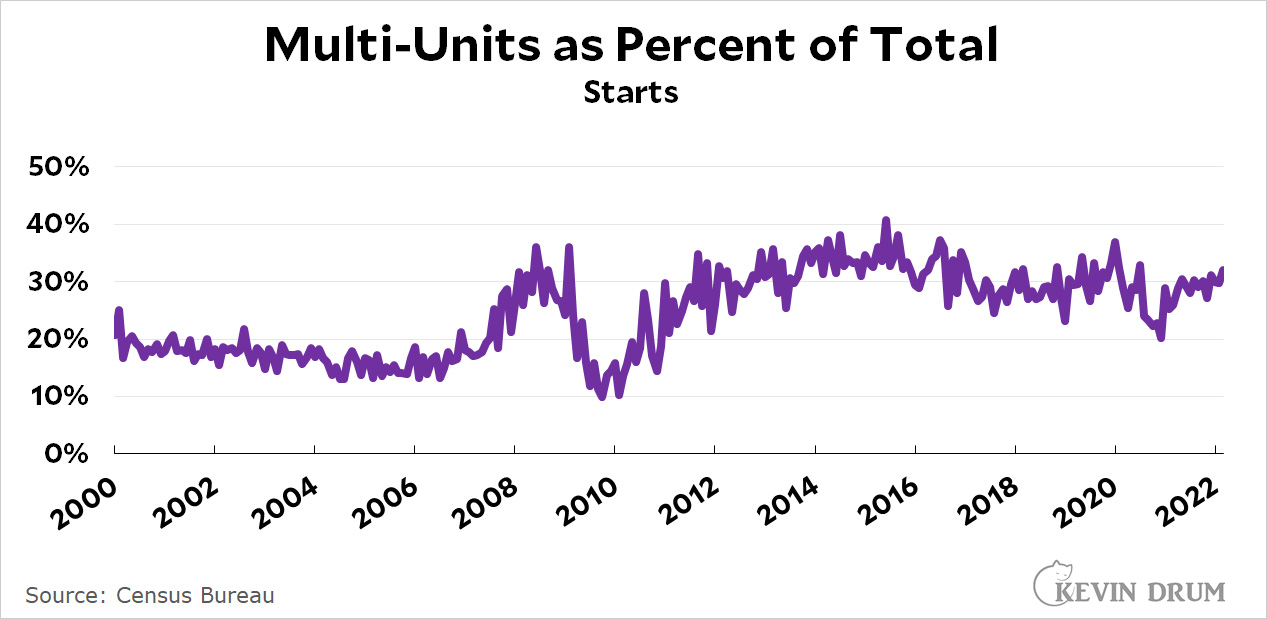

Here is the number of multi-unit apartments being built as a percentage of all housing units:

In the early aughts, multi-unit apartments accounted for only about 20% of all housing units. Today we're building denser: multi-unit apartments account for about 30% of all housing units.

In the early aughts, multi-unit apartments accounted for only about 20% of all housing units. Today we're building denser: multi-unit apartments account for about 30% of all housing units.

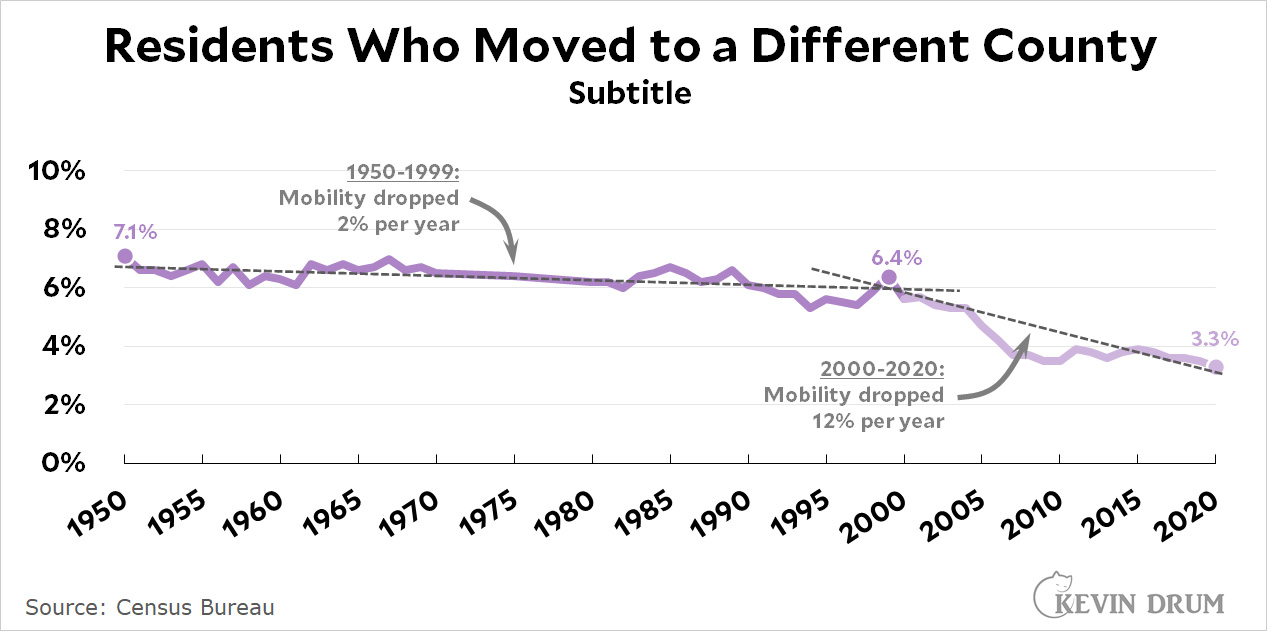

Finally, this chart shows the willingness of people to move away from their current county:

I drew this one on a longer timescale in order to show the inflection point right around the year 2000. For decades, about 6% of Americans moved from one county to another each year. Then, starting in 2000, that plummeted. Today, only about 3% of American families move each year.

I drew this one on a longer timescale in order to show the inflection point right around the year 2000. For decades, about 6% of Americans moved from one county to another each year. Then, starting in 2000, that plummeted. Today, only about 3% of American families move each year.

For some reason, Americans are much more settled these days and far less willing to move for any reason, including things like better jobs or cheaper housing. This is new and it's something I don't really understand, but I have a feeling that among young people this might have more to do with dissatisfaction over housing than the state of housing itself. Feel free to speculate.

I promised you some discussion at the end, and here it is. First off, it's clear that nearly every metric suggests there's not a housing shortage in the US. The only two exceptions are very tiny ones: housing inflation, which is slightly higher than overall inflation, and housing vacancies, which have declined from their bubble peak—though only to about the level of 2005. Overall, it appears that we have plenty of housing.

But shortages are local! The national average may be fine but that doesn't mean there aren't shortages in individual places.

Absolutely right. California is the Great Exception and the Bay Area, in particular, is just flat-out insane. In fact, California alone might account for virtually the entire nation's housing shortage.

But beyond that there are always individual places that are popular and expensive, and there are individual neighborhoods within those places that are even more expensive. These areas change from decade to decade as different cities get hot, and there's really no way around this. This doesn't indicate a housing shortage any more than high prices for Gucci bags indicate a shortage of purses.

Why are you willing to force people to move away from the places they were raised just so you don't have to look at an apartment building near your home?

I'm not. As far as I'm concerned, you may build as many apartment buildings as you want near me. I'm not trying to prevent higher density, I'm just gathering data about the amount of housing in the United States.

But you're still a horrible boomer who managed to buy cheap and now wants to pull up the ladder behind you.

Ahem. Let me regale you with my personal housing history. Out of college, I rented a room from some friends in Tustin for a few years. They had a kid and I moved out to an apartment in Midway City with a roommate. A few years later I moved into an apartment by myself in Santa Ana. A few years after that I bought a small condo in Irvine. Finally, in the early '90s, I got married and Marian and I bought a 2,000 square foot house in Irvine, where we've lived for the past 30 years.

This is very typical. Most people can't afford either the house or the place of their dreams in their 20s, and I was very much one of those. I didn't "get in cheap"; I waited more than a decade until I had the income to buy a place in a fairly expensive area. This has nothing to do with being a boomer or a Millennial or any other generation. My parents went through the same thing, and quite probably yours did too.

But I don't want to live in Peoria or Barstow or Ft. Wayne. I want to live in a big city.

Nobody says you have to live in any of those places. However, you might have to live in Jersey or Riverside or South Elgin for a while until you can afford New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago.

But I don't want to do that.

Probably not, but this isn't a case of the world being unfair or anything like that. It's always been the case that young people have to live with roommates or live in small apartments or live in cheap areas for a while until their salaries catch up with their dreams.

This is all well and good for now, but what about 2022? Rents and house prices are going up a lot now, aren't they?

Maybe. Given the widespread use of rent moratoriums during the pandemic, it wouldn't surprise me if we saw a short-term spike in rents over this year and the next. However, we'll have to wait and see.

What about all those investors snapping up houses so the rest of us can't buy them? Isn't that killing off the housing supply?

No. Housing supply is the same regardless of who owns the homes. Besides, corporate and real estate investors buy a small fraction of all the houses sold in America. There are a few specific areas where they're very active, but that's it.

The real lesson from this trend is not that housing supply is tight, but that in certain areas starter homes are selling too cheaply and apartment rents are too high. That's why it's profitable to buy low-end homes and turn them into rentals. This suggests that in certain places there's an imbalance of what's being built and what people want, but that's likely to balance out before long.

UPDATE: Two of the charts in this post (houses per adult and inflation) have been revised based on criticism received after this was posted.

"If there there were a shortage of housing you'd expect to see more crowding. However, since 2000 the number of persons per household—i.e., the number of persons per housing unit—has gone down. There's less crowding now than there was 20 years ago."

...why can't it be that there are other factors that delay household formation, and therefore there are fewer people per household? It's not like every young person can manage to make roommates work in their 20s, or can live with their parents and find the job they want, or whatever other (totally valid) scenario is given as an example for why young people might delay creating their own household. Also, the population is aging: there are more older people without kids at home now than there were before. So, why can't it be that the number of people per household would be *even lower* if we didn't also have a housing shortage?

You are comparing average home payment (as percent of income) to median total income. You can't do this, because those on the affluent half of the spectrum are absolutely skewing that average lower, as a percent of income.

But overall, you still haven't adequately addressed the fact that housing isn't national. You offer up examples of Jersey or Riverside or South Elgin or whatever, while assuming that those places aren't still in a housing shortage just because they're not within the city limits of the core of the metro area they're in.

Until you look at population level vs. housing units at, at a minimum, the Metro/CSA level, you haven't addressed this. State-level might be OK, with the proper additional context. I cited numbers for the top 10 (or 12? 15?) metro areas at the time before the last time you posted this "national numbers are OK/in line, so we don't have a shortage" stuff - and it was pretty obvious that over the last 20 years, housing units haven't anywhere near kept up with population growth in all but a couple of those places.

Census Bureau has the data.

...why can't it be that there are other factors that delay household formation, and therefore there are fewer people per household?

If people were delaying forming new households, the average size of households would be increasing (more adult children living with parents), so we wouldn't be seeing "fewer people per household." We'd see larger households. Per the numbers Kevin provides, we're seeing just the opposite. AFAIK that's an old trend.

It's true we don't have the housing abundance that would be agreeable in the Bay Area or Manhattan,* but precisely because so many digitally-connected media people live (or want to live) in such areas, we're getting an exaggerated view of the problems of scarcity and affordability.

I do think one factor that might play a role in all this is the simple demographic/physical expansion of our (especially blue) urban areas. They're bigger than ever before, and they also require more space (even as there's been some increase in density at the cores). Let's pick on one pricey blue metro: a lot more people live within, say, 50 miles of Seattle's CBD than was the case a half century ago. That means more people bidding up the cost of housing units within easy commuting distance of the greatest concentrations of employment (and yes, NIMBYism intensifies this dynamic, as does the decline in crime). So, nowadays, the equivalent of what you could do in 1970 (rent a cheapish** apartment not too far from downtown) means living 20 miles outside of the city. But you're still in the metropolis.

**Certainly if films/TV/books are anything to go by, making the rent has never been easy—especially for ordinary workers who can only afford the cheapest accommodation.

Ah, true on the household size/formation math.

It's not just Seattle and San Francisco and NYC and LA and DC. Housing prices are jumping up in mid-size cities across the country. It's completely anecdotal, but it sure *feels* like demand is outstripping supply in the places where people want to live.

There's also the housing units vs. population growth in various metros thing. When I looked at the top 12-15 (I forget how many, really) a few housing-posts ago, it was like... Provo, UT, was one that stood out as having kept pace with population growth for the last 15-20 years while almost everywhere else fell rapidly behind their population growth, when comparing % growth of population vs. % increase in housing units. Some places were very far under the growth rate, which was completely unsurprising.

I remain disappointed AF that Kevin still hasn't gone to the FRED chart for housing starts. It's clear as day that we're still underbuilt from the housing bust in the early- to mid-2010s.

Agreed. Housing is regional, and so are jobs. People in the middle-to-lower end of the income spectrum often cannot afford housing within a reasonable commute of where they work. Transportation and low-wage jobs are big problems in regions like NYC, Boston, etc. We need more low- and middle- priced housing for families, and higher wages, better transportation options at the bottom to solve housing crisis--in more affluent areas (which often depend on middle and low-wages workers--dining, delivery, cleaning staff, etc.)

"In the early aughts, multi-unit apartments accounted for only about 20% of all housing units. Today we're building denser: multi-unit apartments account for about 30% of all housing units."

and

"If there there were a shortage of housing you'd expect to see more crowding. However, since 2000 the number of persons per household—i.e., the number of persons per housing unit—has gone down. There's less crowding now than there was 20 years ago."

I'm in Canada where the data is much more clear on the units getting counted in these housing starts being way smaller, like 1 bedroom vs 3 bedrooms in the 70s, maybe it's different for US. This is a *huge* accumulating impact. 2 boomers in their grandfathered 4 bedroom and 3 20 somethings in a 1 bedroom get to your average. The 2 retirees effective demand for their long held 4 bedroom house is locked in politically and sentimentally, so I don't think it's wrong to say we're left with supply to deal with the 3 people stuck in a 1 bed condo.

so I don't think it's wrong to say we're left with supply to deal with the 3 people stuck in a 1 bed condo.

Household size continues to decrease on average in the US.

Longer-term, I do think it'll be interesting to keep an on average size (ie, area) of housing units. I think it's a fair bet that we'll see this number decline in the coming decades if more density is green-lit. But I don't believe this is a very useful proxy for "crowding" —for the latter you really do need to look at number of persons per household. Many people find excessively large homes to be unnecessary and costly, especially if it means being dependent on a car, and living further than they'd like from city amenities.

I also think it's forfeiting the game to the rent-capturers to measure things as percentage of income: food pre 1960s was 20% of income, now it's <10%. If food producers conspired to notch prices up the horizontal demand curve to get to 19% of income next year, whether or not people have paid similar rates before or are not literally starving, there's a supply issue.

There's reasons land values will scale with income near urban cores. But we shouldn't take it as a given on a national scale, especially knowing land/farm prices are comparatively negligible.

“ California is the Great Exception and the Bay Area, in particular, is just flat-out insane. In fact, California alone might account for virtually the entire nation's housing shortage.”

Shocker that someone from California thinks that California is the big exception and only crazy things happen in California…

I think this is slightly unfair to Kevin, California is the 5th largest economy in the world, add Texas and Florida together and they do not add up to California. California has an outsized influence on statistics nationwide simply due to the money and economic activity. Has nothing to do with where Kevin lives it is just simply basic economics.

Shocker that someone from California thinks that California is the big exception

Well, I'm from Massachusetts and I, too, think California is the big exception (especially the Bay Area, which is ludicrously expensive).

I'm in the SF Bay Area, and house prices are crazy. But, then again, they've been crazy for a long time (not counting the big recession, when prices dropped by about 50% in my area. We've made that back plus another maybe 25%.) Us retired boomers have seen our values rise, crash, and rise again in the last 20 years.

I think CA has an outsized effect on pretty much all events, costs, trends, etc in the US.

During the pandemic as shown on the graphs, people did not want to move, dealing with selling a home, buying a new one etc was just too much with everything else that was going on. So there was a dip in supply starting in 2020, then companies started letting people work from home, these are upper middle income folks that no longer have to commute every day, dealing with buying and selling real estate has become a major pain in the ass, so unless you need another bedroom for a new kid on the way and you don't want to just add on to your existing home for that, people just don't want to move.

Uncertain world and national environments also lend themselves to "wait and see" attitudes, you already have your house or apartment, you know what you have, why take a chance on ending up with something not as good as where you are right now. If the pandemic has shown me anything its the grass is not necessarily greener anywhere, except in your own yard, after you water it, while staying away from anyone who might give you a cold that will kill you.

Then of course we now get to contend with rising interest rates, finally, now maybe savers can start getting more for not spending every dime they make. With higher rates come higher payments, so that $500k loan you could afford on a $100k income is now about $400k. For first time home buyers this is going to price a portion of those buyers out of the market for the time being. In my local market we are already seeing prices heading downward and homes that used to sell in a day are taking a month. This cooling off on the buy side will increase supply and reduce or at least maybe stabilize pricing to some rational and normal increases.

One other thing we have to talk about is the water problems in the Southwest, Arizona, Nevada and Southern California are simply going to have to quit building housing because there is just not enough water to go around as it is. The Colorado river has basically been maxed out and simply cannot support any more human usage with out some pretty major changes to the water usage plans for agriculture and cities.

This all adds up to uncertainty, at least in these local markets, what happens when a human is uncertain? They put the choice off for as long as possible. Who wants to buy at the top of a market and who knows where the market is going to be in 3 months? I will just wait a little while and see how things shake out.

I agree with Kevin, there is not really any more of a housing shortage now than at any other time in the last 50 years. There is just a ton of uncertainty and weird economic problems that most folks have never dealt with before.

My state has seen a decline of 28% in number of low cost units. Many other states are similar or even worse. I think there’s a mismatch in housing production - zoning regs often mean that housing built are higher cost housing unit and not affordable to those with lower incomes. There’s a diminishing number of units at lower end of market available. This has been predicted for decades and it’s biting people in the hind quarters.

Talk about how there’s no housing shortage all you want but I work at an organization that, among other things, help people find housing. And it’s awful out there. Impossible to find housing for many.

Not only are prices different in different regions, but different forces are at work driving the prices up at different rates. In our region, which had a lot of empty second homes, many people moved from their "first" homes to live here so they could work remotely, in a resort area with a seasonal economy. They were followed by a lot of people who decided to buy homes here and work remotely. On top of the housing market recovery, this drove up the median house price in our town. I moved here six years ago and bought a house that cost the median price; my house is now worth nearly twice what I paid for it.

There is plenty of building going on, but almost all of it is far above what most can afford. Multi-family units, because of NIMBYism are being kept out by the locals. So there is little to no new housing stock for renters and rents have climbed accordingly. The result has been that young people who grew up here can't find jobs that will pay for the housing that's available, and they often leave. This is affecting the job market -- it's getting hard to hire people for either seasonal or year-round positions because they pay hasn't kept up with the rate of inflation in housing prices.

I think that household size is the defining factor that Kevin is missing.

I do a lot of divorce work, ( I am good at preventing people from being crazy...an odd talent, but it is mine)...and a standard but true argument in my field is..."Your Honor, two families cannot live as cheaply as one..." An obvious truth maybe, but with children being shared, two housing units are now off the market where once there was one.

Likewise, even at my ancient age, I am seeing women and everyone, including myself, have homes that easily could accommodate a family of at least five.

We are greedily, but happily, singly occupying the housing stock.

I believe that these two factors alone are driving the lack of available housing....what is available is way underutilized! (which, BTW, is exactly as I want it.

In former days, all of our houses would be full of various generations of people.

No so today.

Best Wishes, Traveller

An obvious truth maybe, but with children being shared, two housing units are now off the market where once there was one.

Sure, but the supply of housing isn't fixed. New housing units are released onto the market every day in America. If the phenomenon you describe were actually crimping the supply of housing, we should see it appear in the statistics. But we don't see this.

Maybe it does show up in the data.

Population is stable, yet the demand for housing is higher if 1 household becomes 2 households.

Of the provided stats, the decline in household size seems to support the idea.

“New housing units are released onto the market every day in America.”

Yes. But not in every zip code or school district. My partner and I just bought a house in January, after living together for 4 years prior in another rented housing unit. Our action didn’t single-handedly change People Per Household for our county: our old household had 2 people and our new one does too. But our old apartment was 3 bedroom and now we have 6 bedrooms for just the two of us… meaning some other family of 6 or more may have just lost their opportunity to buy a house. (Meanwhile according to the census bureau, our county added 6,000 people over the last year, but only 553 housing units of all types. At 2-3 people per new unit, that’s still over 4,000 people somehow cramming into existing units.)

Just eyeballing....but the recent years in the first 3 charts dont make sense when taken together.

From 2000 to 2008, we see new housing outpacing population growth, a slight reduction in household size and an increase in vacancies. These 3 data sets are agreeing with each other, telling the same story.

2008 to 2011, population outpaces housing, household size stabilizes and the vacancy rate falls slightly. Again, the data sets make sense together.

But the problem comes from 2011 to 2021. Here we see housing slightly outpacing population, household size shrinking....but vacancy rates fall dramatically. How can this be?

Looking at other data sets, we see home prices and monthly payments increasing dramatically from 2011 to 2021.....which again raises doubts that the supply of homes is really keeping up with thr demand for homes as is implied in chart #1.

Not included is data that shows over ter last 10 years we have seen a huge increase in the population of typical first time homebuyers (mid 20s to mid 30s) and a reduction in the population of people who don't need separate homes (under 18).

We also don't see any data on second/third home ownership, which we shouldn't assume to be stable over this time period. We know that the number of homes available for vacation rentals has increased dramatically, but I'm not sure it amounts to a significant number of total homes taken off the market.

Great data set....but Kevin's conclusion that starter homes are selling too cheaply appears completely unsupported by evidence. I've never heard anyone, anywhere say that starter homes are just too cheap and there is certainly no data presented to make that conclusion.

If there are plenty of houses, prices should be low, right? But they aren't - nationwide the average price (corrected for inflation) is higher than even in the 2006 bubble:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=OvTq

It is true that the problem is much worse in some places than others, but when the national averages show the high prices, then it is a national problem, not just in "certain places". And this is not just the most expensive houses either - median prices show the same thing as average prices:

https://dqydj.com/historical-home-prices/

This is not just a pandemic problem either - prices have been rising since 2011.

Kevin obviously does not have an explanation for the high prices, which are a proof that houses are in short supply in the market. Nor do I for that matter. Of course what determines market prices is not the total number of houses, but how many are up for sale and how many people want to buy them. People who are just moving do not change the total, so the market would ultimately seem to depend on the number of new buyers versus the number of new houses. I have seen a number of articles in the media about why prices are high, but they don't really have the answer either. Economics can be very complicated.

How much can a house buyer afford to pay for a house? By traditional banking economics the size of your mortgage is limited by your income in relation to the mortgage payments, which are determined by the interest rate. But in the bubble of 2006 the banking industry ran wild and let people have mortgages that they really couldn't afford. Are banks doing this again? If so there is more money available and prices will be bid up in a bubble again. But aside from that mortgage rates have been near or below record low levels since around 2012, until just recently. This also means that mortgages can be larger and there is more money available in the market to bid up prices. So as Kevin says prices may need to go up under current conditions, especially in the lower part of the market. However, it seems doubtful that this could account for the very great increase in real house prices since say 1995 (about 60% according to the FRED graph I linked). There are many factors operating, and they are not necessarily all a matter of people acting rationally. Kevin's graphs on supply of houses do not explain the 2006 bubble, so that is an example of how prices can be influenced by things other than the number of housing units.

Real prices are below 2006.

Prices are “high” mainly because the distribution of homes has lots of distortions. For example, in most metro areas, the bad side of town has empty homes you can snap up for real cheap… but then you have to live with the higher possibility of being killed or robbed, as well as send your kids to crappier schools. So they go unbought for long periods of time. Meanwhile, the good sides of town get far more offers, so their prices keep increasing over time. These areas are usually the only ones that “count” when people say “X city or county is too expensive.” Those people are (reasonably) already discounting for the (sometimes vast) inventory of bad neighborhood houses in that area that aren’t going to sell, no matter what.

It’s like saying “we have enough food in our grocery store so that nobody needs to starve” when it’s the week of Easter and the only thing people want is a spiral ham which has been sold out for days. The former statement is still true, but the lack of a specific food item at a specific store on a specific date is disappointing to lots of people.

Also this geographic distribution housing problem holds true nationally too. You can buy a cheap house tomorrow in most parts of largely rural states like, say, West Virginia. But then most people who aren’t retired, wealthy or independently employed would need to actually find or be gainfully employed soon after moving into that affordable WV home. There’s the rub. No matter how many homes are created or become affordable in rural areas, they don’t really count either towards the national housing problems, because very few people can afford to live in them and also simultaneously still remain employed somewhere.

In NYC the "bad" side of town has turned into the "good" side of town. That's called gentrification. Hence, more pressure on low-income individuals and families, and higher incidence of homelessness, families forced to move when rents go up or jobs are lost.

When both the mean and median prices have gone up it is not a matter of just a few areas. It means that most people buying a house have to pay more.

If there's a housing shortage, maybe it's because the definition of an acceptable house has changed. Kevin and Marian are living in 2,000 square feet. My in-laws raised 3 kids in a 1200 square foot house, which incidentally is the size of the house my wife and I occupy (no kids, bought in 1976). The size of houses has increased over the years--see this discussion https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/average-square-footage-of-a-house#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20the%20most%20recent,people%20over%20the%20same%20period.

Everyone who wants a house, wants the best and biggest they can afford in the best school district they can locate. In short they must keep up with the Joneses. More and more if you can't afford that house, I suspect you fall back to a condo in a multi-family building, accounting for the increase, and I suspect the condo is smaller than median house.

Whoops. Marginal Revolution referred to this study on mobility--doesn't quite jibe with Kevin's declining mobility:

"Previous research has found no change in mobility at the national level during this time period, but we show that this hides substantial increases and decreases in mobility at the local level. For children from low-income families, there is convergence in mobility over time, and average differences by region become much smaller. For children from high-income families, the geographic variation in mobility becomes much larger. Our results suggest caution in treating mobility as a fixed characteristic of a place." https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927537122000598

Don't quote marginal revolution around here if you want people to take you seriously. If what the article says is correct, I'm sure you can cite the same data elsewhere.

I believe that people are conflating two distinct albeit related issues: housing shortage and housing crisis. Also real estate markets have a strong regional bias. Combine these factors with overall sociocultural trends allows one to understand the situation. I don’t have a firm conclusion where things are but my sense is that the current real estate economy is being driven by dense metropolitan areas combined with regulatory restricted construction. There is no doubt that housing represents an increasing cost of new households and this is indeed a problem and even a significant problem in certain areas. The way to attack certain bubbles is to pierce the cause in the several situations: zoning changes, wage growth, corporate decentralization, better public spaces to address congestion, etc., through a corporate/government partnership.

Here's some data from Fred and the Census:

2000 to 2021

Total Housing - up 22.7%

Population 24 and older - up 25.1%

2010 to 2021

Housing - up 8.1%

Population 24 and older- up 10%

Looks like a shortage to me.

If average household size has decreased and second home ownership has increased, this shortage is even greater.

Has Naked Capitalismbeen memory-holed? Once upon a time they were my go-to for aggregated housing stats.

What did I miss? that's Naked Capitalism.

Well, that's all dandy and all due respect. But I live in a growing rural town of 20k. Our general store is nearly always out of my shoe size. This has been true for 20 years and more. I don't understand why they don't fix that. If I don't buy when the new shipment comes in, it's gonna be six more months in this pair. The whole time, the shelves are full of shoes. We do not have a shoe shortage, because the shelves are full of shoes, what'a the problem? But I cain't get no shoes: what fits me is all gone.

Same difference with housing. I don't care if you got numbers up one side and down the other: I cain't get no house; what fits me is all gone. These numbers don't represent the problem, and don't hold the solution.

I think unless you actually talk to a researcher who thinks there is a housing shortage you are going to be swinging in the wind.

+1

Is this long post how Orange County Republiqan Kevin Drum is dealing with the French rejection of Marine Le Pen's Antiwoke Agenda?

Sorry your candidate lost, buddy.

Bruh.

It doesn't escape me that you used total housing vacancy rate rather than rental vacancy rate (https://bityl.co/Bvxg) which I pointed at previously.

When people want to ask why is the rent too damn high, I think the answer is obvious. Poking around the edges -- such as total housing inventory is wasted energy. Why waste energy?

If you want to know why housing costs more now, then you have to consider the land-use laws, the 2-year cycle of the building code, the cost of building materials, and the effects of tighter immigration controls.

-- Up until the last two years, most residential codes strictly limited the number of units allowed per lot. Starting with Minneapolis and then moving to the west coast (Portland, etc.), there's been a serious reconsideration of SFR zones. The effect of 30+ years of limitations on SFR zones won't undue themselves in a matter of a year or two. There are other requirements at the local level, eg on-site water treatment, that weren't in place 10 years ago, either.

-- With every 2 year building code cycle comes (usually) more construction requirements, specifically higher energy efficiency measures, but also additional life-safety requirements. You could not get a building permit in 2022 based on the same blueprints and specs of a house from 2016. Some places 20 years ago you could build a single-story home with 2x4 exterior studs. Not anymore. You need 2x6 because the code-required insulation needs the depth of a 6" stud.

- Since the pandemic, 2x6 wood studs and plywood now costs 3-4x more. Metal stud prices have risen so quickly, but only slightly less (~2x) than wood. Concrete is up 20%. Some things haven't changed or have gone down, but most of the basic construction materials have gone up, up, and up even more since the start of the pandemic. Some of this can be easily resolved by eliminating the wood and steel tariffs. There is so much unfulfilled demand that eliminating the tariffs won't immediately result in domestic job losses.

-- A big way residential construction held down costs was immigrant labor. Through Trump, and now with Biden's continuation of Trump's immigration policies, the working nonresident population in the US had shrunk. That's easy to miss if you're in a sector that does not rely on nonresident labor, but it matters a lot when your specific trade is made up of between 15-30% of your workforce. The backlog means fewer phone calls answered and higher prices.

Wrong. Trump is irrelevant. Most of the policies you talk about started under Bush's second term and continued on. Immigrant labor simply was never that huge except for a few years with abnormal high building.

Another idiotic poster with the Trump obsession. Get over it. Trump's immigration policy was not any different than Obama outside a few show pieces. Even the afamed child separation policy was Obama's including the doctors who did unsanctioned experiments were hired in the Obama era.

Like most morons, you don't know a thing.

Reuters:

No one saw this coming, except people who understand Econ and History, I guess.

I can't resist. https://bityl.co/Bvzv

The basic problem seems to be that there is a shortage of housing where people can get good jobs. Companies really need to embrace WFH if they want to be able to retain the best employees. I suspect one reason the big tech companies have ridiculous lavish perks in the offices is they know many employees live in hell holes they don't want to go home to.

What's the source for the assertion that investment property and rental market (i.e. AirBnB) aren't squeezing the market?

An eyeball at where AirBnB (by itself) shows an unequal distribution across the nation. Investment properties are not located in places without jobs or expansive housing markets. Second+ homes are located all-over but I wouldn't assume a linear relationship between housing stock and housing prices.

I actually went down the Case-Schiller rabbit hole for a bit, and am sorry to say that I don't know that any amount of graphs can explain this issue.

That's because housing is so geographically dependent.

Right now, in the 90210 are code 45 of the 150 agent listings are over $20 million.

When people talk about a "housing crisis" they not only mean the crisis in affordability, but what is not mentioned, out of sheer politeness, is that the geographical limits on land apply all the way up the line.

So, a lawyer who does not also run Legal Zoom or something is never going to be able to buy one of the top third of homes in Beverly Hills. I do assure you that lawyers I knew from prior generations who bought in the 1970s or 1980s often had homes in the top third of Beverly Hills.

There is only so much of Beverly Hills to go around. And that applies to land in general.

I think Case-Schiller shows that there is in fact a drag on housing appreciation, but its a losing battle for the prospective homeowners, just as its a winning battle for existing homeowners.

Its only logical that the US would end up with this issue, really. We had tons of land at one point, still do, but only so much land in the areas which are desirable.

OK, I’m in with your contrariness and agree there’s some sloppy thinking (and calculating) about housing.

But are you making a.mistake in not factoring out vacation homes?

They are part of the “housing units” you show in your graph as rising faster than population. What happens if you subtract them? Is there still no housing shortage?

Here in Vermont some 17% of our total units — that’s about 58,000 of 336,000. — are vacation homes, occupied in the summer and a few weeks for skiing by folks whose really houses are in Connecticut, N.J, and the like. So we don’t really have 336,000 housing units available for people to live in. We have (I’m good at arithmetic) 278,000.

That seems to be not enough. So maybe we at least rally do have a housing shortage. And maybe so do other places, though clearly our vacation home % is among the highest.

Or have you accounted for this?

Average household size is misleading. Yes, it's smaller, but it's also significantly older. The age group most likely to own their home, those over 60, has increased dramatically in the last 20 years, as has gray divorce. Meanwhile the number of child free adults has increased dramatically. Fewer families of 4, more families of 2.

There is a national housing shortage. It will ease as the supply of assisted living gets completely overwhelmed, but the homes built in the 1960s and 70s that become available over the next two decades will need almost as much work as new homes.. but at least the lots will open up.