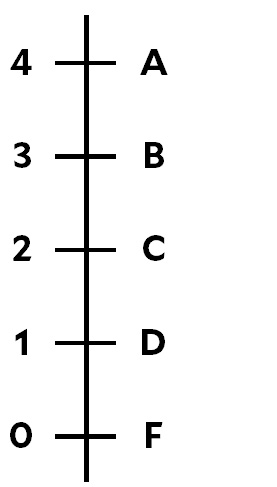

And now for something completely out of the blue. Let us consider the most widely used grading scale in American schools and colleges. It looks like this:

A straight-A average is a 4.0. A B+ is a 3.5. The lowest grade is an F. Even if you blow off an assignment completely, that's still the worst you can get. Zero. There's no such thing as an F-.

A straight-A average is a 4.0. A B+ is a 3.5. The lowest grade is an F. Even if you blow off an assignment completely, that's still the worst you can get. Zero. There's no such thing as an F-.

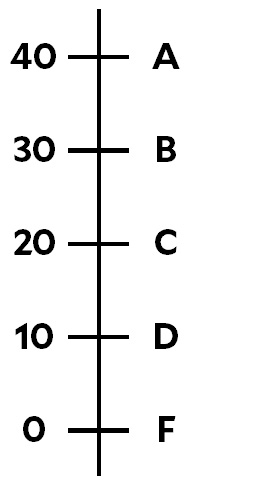

Now, just because, let's multiply everything by ten:

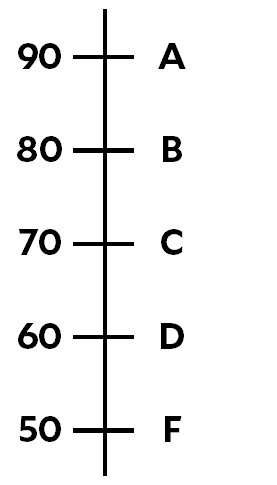

This is exactly the same thing, right? We've just decided to use multiples of ten so we have a little more flexibility between letter grades. Now let's add 50 to everything:

This is exactly the same thing, right? We've just decided to use multiples of ten so we have a little more flexibility between letter grades. Now let's add 50 to everything:

I hope everyone will agree that we've still changed nothing. An F is now a 50, but it's still the same distance from a D as a D is from a C. This should look familiar since it's the numerical scale most commonly used in schools.

I hope everyone will agree that we've still changed nothing. An F is now a 50, but it's still the same distance from a D as a D is from a C. This should look familiar since it's the numerical scale most commonly used in schools.

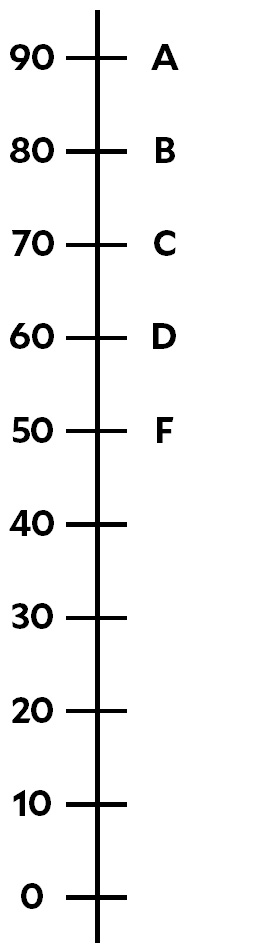

But not quite. What we actually do in real life looks like this:

Whoa! We just arbitrarily added 50 points below an F. Does this make any sense? Why did we take the original scale and basically add a whole bunch of space below the old zero point? Hmmm.

Whoa! We just arbitrarily added 50 points below an F. Does this make any sense? Why did we take the original scale and basically add a whole bunch of space below the old zero point? Hmmm.

Now then: What's my point? Why did I write this? It's a response to a piece in the New York Times about alleged gaming of the grading system in some high schools:

What's not helping? The policies many school districts are adopting that make it nearly impossible for low-performing students to fail — they have a grading floor under them, they know it, and that allows them to game the system.

Several teachers whom I spoke with or who responded to my questionnaire mentioned policies stating that students cannot get lower than a 50 percent on any assignment, even if the work was never done, in some cases. A teacher from Chapel Hill, N.C., who filled in the questionnaire’s “name” field with “No, no, no,” said the 50 percent floor and “NO attendance enforcement” leads to a scenario where “we get students who skip over 100 days, have a 50 percent, complete a couple of assignments to tip over into 59.5 percent and then pass.”

At first this sounded outrageous. But then I realized I was just having a knee-jerk response to a change in the way things have always been done. Upon reflection, I realized that the way things have always been done makes no sense. On the scale we started with, which goes from 0 to 4, there's a gap of 1 unit between an F and a D. But then we do a bit of scaling and decide that a real F is a zero and a D is 60. Suddenly there are six units between an F and a D compared to one unit between all the other grades.

So who's gaming who?

Interesting Kevin. Did you haves a little dinner with your wine?

Math is hard.

To pass a course, students are expected to achieve defined core learning outcomes. That means they've "passed", and get an arbitrary score of 50%, a bit like average IQ is set at 100. They can fall just short, and get 45%, or display comprehensive ignorance and get 0%. There is little point awarding different grades of fail to students who haven't reached the minimum required level of knowledge. They need to retake the course to get credit for it.

Students can also demonstrate learning outcomes over and above the basic core requirements, which result in higher marks up to 100%, with corresponding grades. There is value in doing this because it differentiates students who've barely mastered the basics from those who have acquired deeper, more thorough knowledge of a course (employers in my experience pay too little attention to the grades awarded to job applicants).

That at least is the longstanding approach to assessment in Australian universities. I've no idea whether and how it might have been bastardised in American high schools.

High school science teacher here. So I am acutely aware of this issue and have exhaustively examined it from all sides. Kevin is exactly right, the current grading system is inequitable. Here is an example to illustrate the point.

A student has is given two assignments.

On the first one he does perfect work and receives a 100 or A+

On the second one for whatever reason he misses it and gets a zero or F

In an equitable world, an A and an F would average out to a C. However in this case the A and F still average out to an F because a zero carries 6-times the weight of a 100 in a traditional grading system.

There are two ways to do it differently and both get you to the same place. You can scrap the traditional scale of F = 0-59, D = 60-69, C = 70-79, B = 80-89 and A = 90-100 and replace it with:

0-20 = F

20-40 = D

40-60 = C

60-80 = B

80-100 = A

And then simply grade more harshly such that your students distribute along that spectrum accordingly. Most grading is subjective anyway according to arbitrary rubrics. So for C work that you used to give a 75 you give that same work a 50 under the new scale. And A work that used to get a 90 gets an 80 under the new scale.

Under such a system, a student who turned in a perfect assignment for a 100 and then missed an assignment for a zero would end up with an average grade of 50 which would be a respectable C. So an A and F would average out to a C.

The other way to get the same result is to start the grading system at 50 and simply grade all work between 50 and 100 which is what the teachers in this article are complaining about. Mathematically you get the same result but it rubs some teachers wrong to give a " free" 50 for no work. So the simpler way is to simply distribute the grades A - F evenly on the 100 point scale as I just described. That way no one gets free points for doing nothing. But each letter grade carries the same point weight.

It really is dumb. I'm sure there are plenty of teachers who rationalize the current system with "well, a zero should be way worse than a run-of-the-mill F - you should be rewarded somewhat for at least attempting to do the assignment even if you sucked at it."

Besides the obvious objection here (that this makes no sense - the punishment for blowing off the work entirely should not be this disproportionate to the punishment for doing very shoddy work) it's pretty clear to me that this logic was not something the people who originally designed the scale ever had in mind. If the kid-lit I read in the 1980s was any indication, teachers in previous decades never threatened kids with the dreaded zero for a grade. That had to have been a relatively recent invention.

I think in the olden times, grades were entered and calculated by hand. Computer grading systems where the computer calculates the grade and teachers are just data entry clerks are relatively new.

Back in the day when I was in HS in the 1980s, teachers would enter letter grades in a big paper gradebook and then average them out. So your A on the first test and F on the second test would average out to a C. They would just convert missing grades to Fs and then use the 4-point scale to calculate the final grade in the class.

So a typical teacher would assign numbers 0-4 for grades F-A then add up all the points and divide by the number of assignments. Which is exactly the same as I just described except instead of a scale of 0-100 you have a scale of 0-4

A student receiving 10 grades of

F, D, A, A, B, A, C, B, A, A would earn 29 points which would average out to a 2.9 or C+

This is really silly.

F means Fail (that is why most schools do not have an E grade).

A fail can be anything from a 59 to a 0.

When you average test grades to get a score for the year, obviously a 59 on a test should be treated differently from a 0.

Why is this even an issue? Any kid who does not have a mental disability and remotely tries should be able to get close to a D.

It's because now a days, they use the numbers instead of evening out the numbers with the five point scale.

Right... and why shouldn't they use the numbers?

There is a big difference between a 90 and a 100. They should not be treated the same.

There is even more difference between a 59 and a 0.

I think the best response to Camasonian's argument is that class assignments use a finer grained scale than the GPA scale, that is, they use 100-0 rather than 4-0. So you can in essence think of the class assignment scale as:

100-90 = A

89-80 = B

79-70 = C

68-60 = D

59-50 = F in the first degree

49-40 = F in the second degree

.

.

.

0-10 = F in the sixth degree

A student who receives a 100 on one assignment and who fails to turn in the second assignment has received an A and an F in sixth degree, which averages to a 5, an F in the first degree. Fair!

If anything it is the GPA scale of 4 - 0 that is unfair. You could argue it is unfair to the kid who fails a course with a 59% overall course average that he/she gets the same GPA 0 that the kid who (say) fails the course with a 12% overall course average gets. On this way of thinking, why not do away with the GPA scale altogether and just use a fine grained GPA 100-0 point scale that combines together all of a student's overall course average? Kid X would have a GPA of 93, kid Y a GPA of 72, kid X a GPA of 81, etc.

In truth, though, combining all course averages into a GPA on a 100-0 scale seems to me a bit harsh. Getting an "F in the sixth degree" in a course would tank your overall GPA in a virtually irreparable way. The current GPA on a 4-0 scale represents a kind of merciful "second chance" system that allows for a recovery from one or two F grades. That seems preferable to me.

I guess, then, that I'm happy with the current system: the fine-grained grading of class assignments and the more forgiving coarse-grained ranking inherent in GPA averages. I don't see the necessity of using the same ranking system for both class assignments and GPAs. They serve somewhat different functions.

(Side note: I teach at the university level.)

I used to teach (STEM things) at university as well. I especially endorse your remark about how the two systems are different.

To me, there was a big difference between not doing anything - skipping a quiz, or not turning in a problem set - and struggling. I never had a student turn in work that got a zero or anything close to a zero. This is college. You don't have to be here. Why take the class if you don't want to do the work?

I'm also a university lecturer and I came here to say this but you covered it well.

Oops, a typo in my post above. 100 and 0 average to 50, of course, not 5!!

Just-retired high school social studies teacher here. In my last two years, after reading the book Grading for Equity, I introduced changes that reflected a new understanding of grading. The current grading schemes in my high school had a couple of underlying assumptions:

Your final grade = an average of your scores

Scores = anything that the teacher would like to include in your grade, weighted almost any way they wished, whether the score was an assessment or not.

So the grades were wildly inconsistent from teacher to teacher, even within a department. Students had not idea what their grades represented except the rankings. I raised the issue with administration, but they had no desire to stir the hornet's nest of "teacher autonomy." They saw what happened when they introducted an electronic gradebook -- lots of teacher resistance.

Since I could do it independently, I switched to a mastery-based system my last two years, based on Grading for Equity. Students loved it. So did administration, but they wouldn't push it.

I stopped caring whether a student "did the work." I switched to caring whether the student learned the material, and how well. It made a big difference. It's a classroom, not a factory floor.

That's a great solution. I always was biased to that - I easily mastered alot of classroom stuff - but it equally seemed wrong to sink a student just because they were slower at learning the assignments.

It just didn't make sense to me that the student who was learning slower but caught up in the end should be dinged over the student who didn't learn a dang thing because they already knew the stuff.

Thank you. This is exactly what's wrong with current scoring that I've seen ... it focuses on doing the work and getting credit vs actually learning the material. These are vastly different things. Many students excel at learning but are perfectionists or have issues with inattention ... this puts them at a bizarre disadvantage compared to the worker drones. It is strangely biased against intelligence, and does not engender a love of learning.

I think this analysis is comparing apples and oranges.

Letter grades are really only used on report cards. You get an A or a B or whatever, and that's that. All A's are treated the same. The letters have a "grade point" equivalent so that you can calculate and display a grade point average.

But during the year in class, they use a different system that will eventually be converted to one of the enumerated grades for your GPA... essentially they just track the percentage you got correct for an assignment. In this system less than 60% correct doesn't cut it, and a complete no show is 0%.

They may call 90% of correct answers an "A" for a given test, but getting a 97 is better than a 92, since all that matters at the end of the year is the average of all of those percentage "grades".

We could do away with the mismatch between the systems for more clarity on how you really did, and at the end of a class you could get an A (>90%), B (>80%), C, D, F, G, H, I (>20%), J (>10%), or a K (0%), with a maximum GPA of 9.0. Would this be more "equitable"? Or is the inequity deciding that you need to know more than 60% of something to pass?

If that is your only measure, 60% mastery.

Then all you need is one final exam with a 60% passing threshold with an exam that fairly assessed mastery. No point having any other grades at all.

Well, one point is that a midterm and a final, each covering half the course material and counting half, is less intimidating for the student.

The first comment, by kenalovell, is on the right track.

Say a student is in a class we'll call Math 4.

In an Math 4 class, say there are 400 points total. Only one point really matters: what grade is required to pass? C, B and A are all the same, they're passing. D and F are the same, they're not passing.

Say the teacher has designed the class (set the assignments, exams, chosen the material, etc) so that 280 points or 70% is enough for a C.

Kind of what you're saying, when you ask a student to get a 70% for a C, is that if they can't score any better than this, they don't deserve a passing grade. But also, they have to retake Math 4 before going on to Math 5, where they'll be expected to have learned the material in Math 4 well enough to be successful.

Sure, you can fake-pass them, but what's the point? The student who scores below 70% in Math 4 will not be successful in Math 5. (On average, of course, or with a certain frequency).

Classes have purposes.

Consider also that a score of 70% may in some sense be thought of as 20%, if you figure that any student who passed Math 1, Math 2 and Math 3 should be able to get 50% in Math 4 just on what they know the day they start the class, or at least with a true minimum of effort. It can be better to think of the grade scale as 50 - 100, with scores below 50 indicating that something has gone very very wrong.

To "classes have purposes" I should have added that the example here - preparing for the next math class in a sequence - is just one possibility, and obviously applies well to math specifically. But if learning doesn't have a purpose, why are students doing it?

This idea only applies to sequential classes which generally are science, math and foreign languages. It falls apart completely in social sciences, literature and arts classes. It’s entirely possible to get an F in a freshman “intro to lit” class and then get an A in a “themes of horror fiction” class. Perhaps the books selected for the intro to lit class sucked - they did in my intro to lit class even though I passed with a C! - but then when exposed to horror fiction, the student couldn’t get enough of it. There’s way more subjectivity in some academic subjects which makes the classes non sequential (you could take them in any order), which in turn means a student can go a lot longer before being discovered as struggling to master all materials.

There are three things going on here:

1) How to grade a test—generally as a percentage of correct answers, with below 60% representing failure;

2) How to grade a course with multiple tests—In my time this was calculated from the various test percentages, perhaps weighted;

3) How to calculate a GPA spanning multiple courses—this is based on the letter scale

Two observations:

A) Scoring 100% in one test and missing another is not a C in any school I’ve ever attended;

B) While a student can certainly fail a class, such classes are typically retaken until the student passes, and so the GPA eventually weeds out failed classes.

In my HS you couldn't retake classes.

Most classes I've been in, you could get 0 on a test or assignment, usually for an incomplete, but theoretically just for getting everything wrong. So the scale really was 0 to 100, but 60% (D) was the minimum for passing. I don't remember anything where you would get an F on a test or assignment and that was translated into a 50% of the points.

It's all kind of arbitrary, anyway, depending on how the class is structured. As long as it's communicated clearly upfront and produces reasonable results, who cares about the scale?

I don't have a NYT subscription but this sounds like another in the neverending series of moral panics about grade inflation and how schools are getting soft. They're as frequent and been going on as long as "kids today don't want to work" articles and "these latest trends in how to teach math make me confused and angry!" articles. Older people love them, so it sells papers.

This is how I remember things. If something wasn't turned in, you got 0 points and not 50. An F was any percentage grade below 60, meaning that a 60 percent average was needed for passing. The scenario mentioned in the article would result in a final average of 50, an F. Once this procedural issue is fixed, the system is equitable.

Thank God it’s cat blogging today.

👍Yes - & while still calling Politico "Tiger Beat on the Potomac" - saw here previously that the phrase is still being used - it is appointment viewing on Fridays, but only for Matt Wuerker's aggregation of political cartoons. Must have missed any announcement of his own space there being ended, but the collection has shown one of his recently. Still too many noxious ones by Michael Ramirez there & at The Washington Post.

I've been teaching for 10 years now, and fighting this battle over and over and over again. It's mathematically evident that it's silly to devote half of all points to showing students how terribly they've failed rather than just giving an F. So I don't do it. Still, my grades are frequently the lowest even with a min 50 policy in place, and test scores are the highest. Even better, students' GPAs tend to match what they get on summative assessments.

The more I've argued for this particular molehill, the more I've realized it's about ideology than math. Basically, many people feel that students should be numerically penalized much more for not doing something as for doing it poorly. But the truth in an actual workplace is that there's frequently not much difference between not doing something and doing it poorly. It can even be worse to do something really badly, because then other people have to disentangle the panicked efforts of others before they can fix the problem.

So, to respond. Kevin's right. Very right.

If a student who does zero work is getting a non-zero score then that system is gamed.

They get an F in the end so it doesn't matter.

From the quoted article:

"students cannot get lower than a 50 percent on any assignment, even if the work was never done, in some cases. A teacher from Chapel Hill, N.C., who filled in the questionnaire’s “name” field with “No, no, no,” said the 50 percent floor and “NO attendance enforcement” leads to a scenario where “we get students who skip over 100 days, have a 50 percent, complete a couple of assignments to tip over into 59.5 percent and then pass.”"

It matters.

No, that's not the problem at all.

The problem is that the zero for doing no work carries 6x the weight of getting a perfect score on the next assignment.

A grading system where an F carries the same weight as any other grade eliminates this problem. Which is the whole point of Kevin's article.

"The problem is that the zero for doing no work carries 6x the weight of getting a perfect score on the next assignment."

No, that's not a problem. That's how it's supposed to work.

A student who does no work and gets a zero, but then gets a perfect score next time, *should* still fail with 50%. After all, they only did half of the work.

Think about the kids who grow up with the "zero work gets a 50% score" system - would you want someone like that on your team at work?

I think KD is combining two different things. The 0-4 scale is for GPA. As he said, straight A's means a 4.0 GPA. Half A's and half B's would be a 3.5, etc. But then he gets into grading individual assignments with the 0-100 scale. Standard is 59 and below = F, 60-69 = D, 70-79 = C, 80-89 = B, 90 and above = A.

In any grading system, the kids will game it.

I can see the fustration some teachers may have with awarding 50% of the points to work that isn't turned in. There will be kids who turn in the first few assignments and then completely skip everything else. They may pass the class, but will have learned only the first few weeks of material, setting them up for failure in later classes.

My kid's school used to only grade summative assessments, but kids gamed the system by never doing the formative assignments (why bother if there is no grade?). Kids didn't learn the material and did much worse on tests, so now they are back to adding in grades for formatives.

Beyond the desire to actually educate kids, there is always the specter of graduation rates. Seems like every district is desperately trying to raise grad rates in any way possible. Points for no work is just another way to juice those numbers by making it harder for kids to fail classes.

Oh, it's not the kids who are gaming it. It's the school administration who're gaming the system.

I remember pondering this a long time ago, counting the days until I got out of high school.

One teacher always gave tests in the same format, with the same number of questions, so it was possible to derive the scaling function - I can't really remember, but I think 4 right answers out of 20 was passing.

That class didn't have a curve, but others did and it all looks even weirder.

This was in the 80s. If anyone wants to complain about playing games, well, it has been gamed for literally longer than my adult life, at least. And somehow I rather suspect that Wally and Beaver's grades made no more sense than mine.

For literally anything, conflicting opinions are meaningless outside the context of what interest is being served, and otherwise resolvable with relative ease.

In my mind, the interest being served is preparing students to be reasonably self-reliant adults, and how students are graded is a means to that end. Either it is serving that end, in which case nothing needs to change, or it is not, in which case there are better options, the options can be evaluated in relation to the interest being served, and the best option wins. It's not necessarily easy, but it is simple.

Whether I'm right or wrong about the interest being served, if reasonable minds draw conflicting opinions, then the conflict will be resolved, and at least one of the minds is otherwise unreasonable, likely because nobody likes thinking about what interest is being served.

With all the focus on fairness, we should not overlook an essential element of grading: student motivation.

For better or worse, the motivating payoff for students is the grade, and they are notoriously bad about doing work that will benefit their learning unless there is an immediate reward/punishment in the form of a score that will figure directly into their final grade. (Not so different from the rest of us in other contexts, I suppose.) So, a lot of teachers, myself included, build into the grading system not only items designed to measure what-did-you-learn, but also what-serious-effort-did-you-put-in.

If theoretically a student did all of the work and still somehow learned exactly nothing, they might earn 50% of the points; I would not want to give that student a passing grade, so starting with a grade of D somewhere above 50% is completely appropriate. But of course, it's always more complicated in real life, and that's where including effort-based rewards matters. In my experience, if you don't give students the motivation-by-grade to complete the weekly homework, keep up with the reading, write the short reaction paper, etc., etc., then a lot of them just don't do it, or more likely don't do it adequately, and educational outcomes suffer. If you provide that motivation, students are more likely to do the work, and learn more overall.

Is this approach to grading perfect, or even perfectly coherent logically? No. But it does acknowledge that in the real world of education, grades serve not just as evaluation tools but also as powerful motivators.

I heartily endorse a 50 point floor for missed work because it gives incentives for a student to not give up, and it encourages a student that has given up a reason to start trying again.

Let's say you have a solid C student who averages about 75% on the work they hand in. If that student misses an assignment worth 25% of their grade, they may as well give up for the semester. Scoring 75% on 75% of the assignments gives a failing grade of 56%. At that point, there's no reason to keep trying. If the missed assignment were worth 50%, that student would achieve 69%, a high D.

I know some may say that the 0% F for missed assignments gives incentives to always complete assignments. This is true; however, kids will still miss assignments. What are we to do with those students?

For those who believe an 50% F is unfair, I respond that the 69% in the above scenario is still a low grade. The student is still differentiated from the high achievers, and from the middle achievers who don't miss assignments, so I don't understand what's unfair about it.

Educators care about all their students, not just the high achievers. The 0% F is too big a stick in the carrot-and-stick system grading system. It undermines the educational mission of teaching all students, no matter the achievement level.

I believe grading IS a big issue: however, this is not my issue.

Rather, social promotion, advancing students who historically would have failed (often by lack of attendance/lack of effort) is wrong. For the marginal student, the risk of not graduating, historically, high school had some (I will admit imperfect) incentive. Now, at many high schools, its almost impossible not to pass a class. Further, while weak, there used to be a signal effect for employers of young people: candidate A managed to graduate while candidate B did not.

I'm surprised to say this, but ... I agree with you. 100%.

All through grade/middle school I was good at math. Freshman year of high school (1969) my algebra teacher was, hands down, the best teacher I would ever have at anything in my life. I got the easiest A of my life.

Sophomore year I walked into the algebra 2 class with great anticipation and sat myself down in the front row middle. I was probably asleep before that first class ended. This teacher talked in such a way that he put me to sleep. And he let me sleep. He once chasticed another student for waking me up! "You disturbed his nap!"

When exams came along (I have no memory of there ever being homework,) I would put my name on the paper and copy out the equation that was already right there and try to do something with it, but having no clue what I was doing, it went nowhere. He would give me 3 or 4 (5?) points for that and curve the class so my grade was a D.

And that's what my report card said at the end of the year: D

Which was apparantly good enough, I did not have to take the class again. Algebra has remained a mystery to me ever since.

A couple of decades later his picture was on the cover of the alumni publication announcing his retirement with columns of praise from former classmates. But he was the worse teacher I had in 16 years of schooling.

This is a complex issue but it's easy enough to see where matters of fairness and equity enter in. My experience is overwhelmingly at the university level, and a subset of students who don't attend university are thus excluded from my personal observation, but I think the following claims likely hold up for high school as well.

In my experience, students who turn in assignments but do lousy work aren't interested in doing better. They're doing the bare minimum to get by, either because they hate the subject or because their priorities are elsewhere. There isn't any way to compel someone to learn, and the best you can do is manipulate the "floor" to adjust where these students are sitting.

But students who miss class and assignments? There's a wide range of possibilities. I've seen a range from a struggling student who smoked a lot of weed (and maybe other things) and lacked the basic skills to succeed, to a student who was fantastic in one of my classes, but when taking another the next year had huge attendance issues and turned in late assignments. The change was related to coming out to their family as trans immediately before the second class started. In the old days, he'd have gotten bunches of 0s and failed the course, because that's how I set the floor. But in fact, they turned in all the assignments by the end of the semester, and it was great work: they'd clearly done all the reading and managed to get by even without all the benefits of regular attendance. I've had other students miss work or assignments because they had been raped. At the high school level, I'd expect any number of family-level disfunctions to drive student attendance issues. Rating this work as a 0 and holding the students back simply takes potentially good students and teaches them that they're bad students just because they have an abusive parent, or are forced to act as primary caregiver for a single mom, or whatever is going on.

In high school, you'd also have the students who have given up on HS and are only attending by force. Failing them and not giving them a diploma isn't going to change their behavior. They've written themselves off, for whatever reason.

The students who are gaming the system will game whatever system you give them. The students who gave up can't be forced to change their minds. So you don't help these students much by adjusting the floor or being more generous about missed assignments or missing classes: the outcomes will be similar. You can either help or harm students who miss assignments or classes due to factors outside their control.

The best solution would be to provide our schools sufficient resources that they can identify students who are having trouble, identify the sources of the problems, and try to work with them to address those problems. Of course, that would require a lot more one-on-one work, spending a lot more money, and being willing to spend more money on struggling students than on the top performers.

Strangely, the people most angry about "falling standards" and excessive leniency in our schools tend to be the ones who are least interested in actually helping students. They're angry because these failing/drop-out students haven't been given up on fast enough, that they're consuming resources that could go to "better" students.

One last thought: in HS, I took a Calculus course with five other qualified students. After our first test, the teacher wrote the grades up on the board, and they ranged from 72% to 36%. He then sat down and said, "You are taking calculus in high school. You are all good students. Calculus is just really difficult. By the end of the year, you'll be doing much better." And we were. If the point of a class is for students to learn difficult material or challenging skills, and if they enter the class performing at 100%, then their perfect score reflects that they already knew the material or possessed the skills they were supposedly taking the class to learn. We should want students challenged at the beginning of a unit/year and rising to that challenge across the period of learning. Insisting students should be graded more harshly doesn't seem responsive to the actual purposes of learning, it seems to be an insistence that students already possessing skills should win awards for learning nothing new, while students severely lacking in skills and years behind their peers should be punished for not catching up to everyone else in a single year.

Missing mostly so far is the importance of comments addressing the student as well has ticking off the rubric. IOW, tests, assignments, projects, etc, should be regarded as diagnostic tools, not a hoop your students have to jump through.

I also tell my students that there will be no letter grades until the end of the semester; IOW I make sure they damn well know they're not allowed to convert a numeric score into a letter grade and then treat them as if they were numbers.

If schools allow students to get away with not bothering to actually get an education, the kids who suffer most in the long run will be those whose parents also allow them to get away with it - mostly parents who are low income and not well educated themselves - while the kids who still get the education required to get hired to decent jobs will be those whose parents provide the enforcement that the school won't, mostly parents who are high income and highly educated. So what's the real inequity here?

Discipline is inherently unpleasant and takes a real toll on people, but it is the only way to get people to behave. There are some instances where the benefits of the desired behavior aren't worth the costs of discipline, but this isn't one of them. Most kids are, by nature, too shortsighted to be motivated by the far-off prospect of their labor market performance, but we adults know better, don't we? In this case, the discipline really is for their own good!

No amount of discipline will work if no additional resoures are provided

I agree that resources matter and I've always supported ample school funding. But resources without discipline won't work either.

You are completely very most sincerely correct.

Oh, it suddenly occurs to me that some people might not be aware of the four types of data:

1 Continuos/Ratio - Plus, minus, multipy, divide allowed

2 Interval /Discrete - Plus and minus allowed, but not multiply and divide

3 Ordinal/Ranked - Can be ordered but no math operations allowed.

4 Nominal/categorical - Cannot be ordered and no math operations allowed.

Letter grades fall into the third category because their weights differ. But the both admin and teachers are treating them as if they're in the first category ?!?!

Yes that class I mentioned above were taking statistics ... why ever do you ask?

There is a certain amount of wussieness on this one.

I grew up in Indiana, so this might be regional, but in my time, an A=95 minimum; B=88 minimum. It took a 70 to pass. I can’t remember the exact breakdown for C and D, mostly (and Imma not even going to blush) I hardly ever got one.

Of course this was long ago. When dinosaurs walked the earth.