I'm not generally a New York Times hater, but they sure do know how to overdo things. I mean, is the resignation of Harvard's president really worth five front-page pieces in a single day? I get that their target audience is upper middle class northeasterners, but come on.

Does DEI even work?

For the past year or so, the new hotness on the right has been an all-out attack on DEI—Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. They object to it pretty much everywhere, but most of their attention recently has been focused on universities.

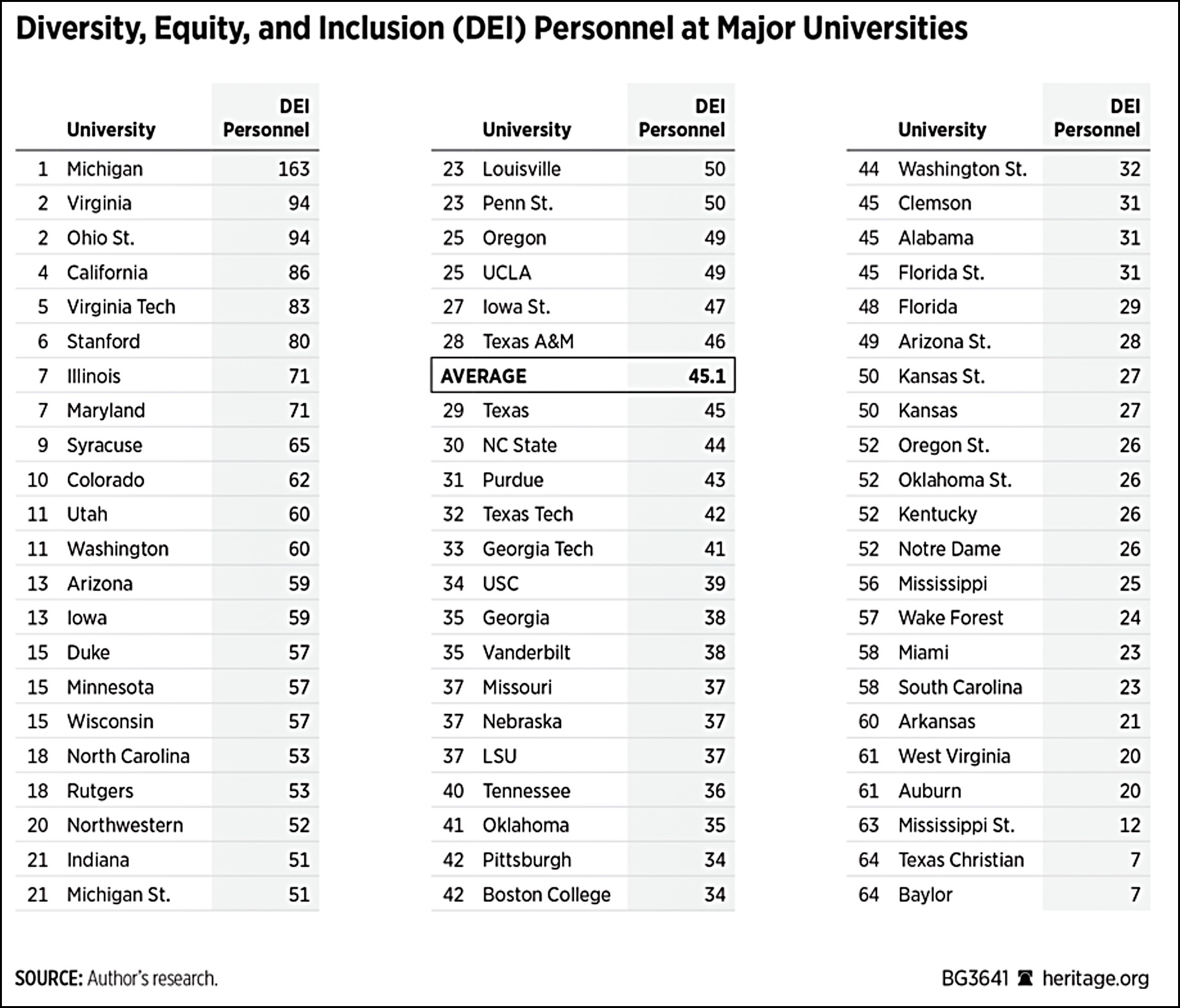

As usual, this got me curious. Unfortunately, it appears all but impossible to get reliable figures for the growth of DEI staff at universities. The best I could come up with was a Heritage Foundation study that tickled me because the authors chose to examine schools in the Power 5 football conferences.¹ Here it is:

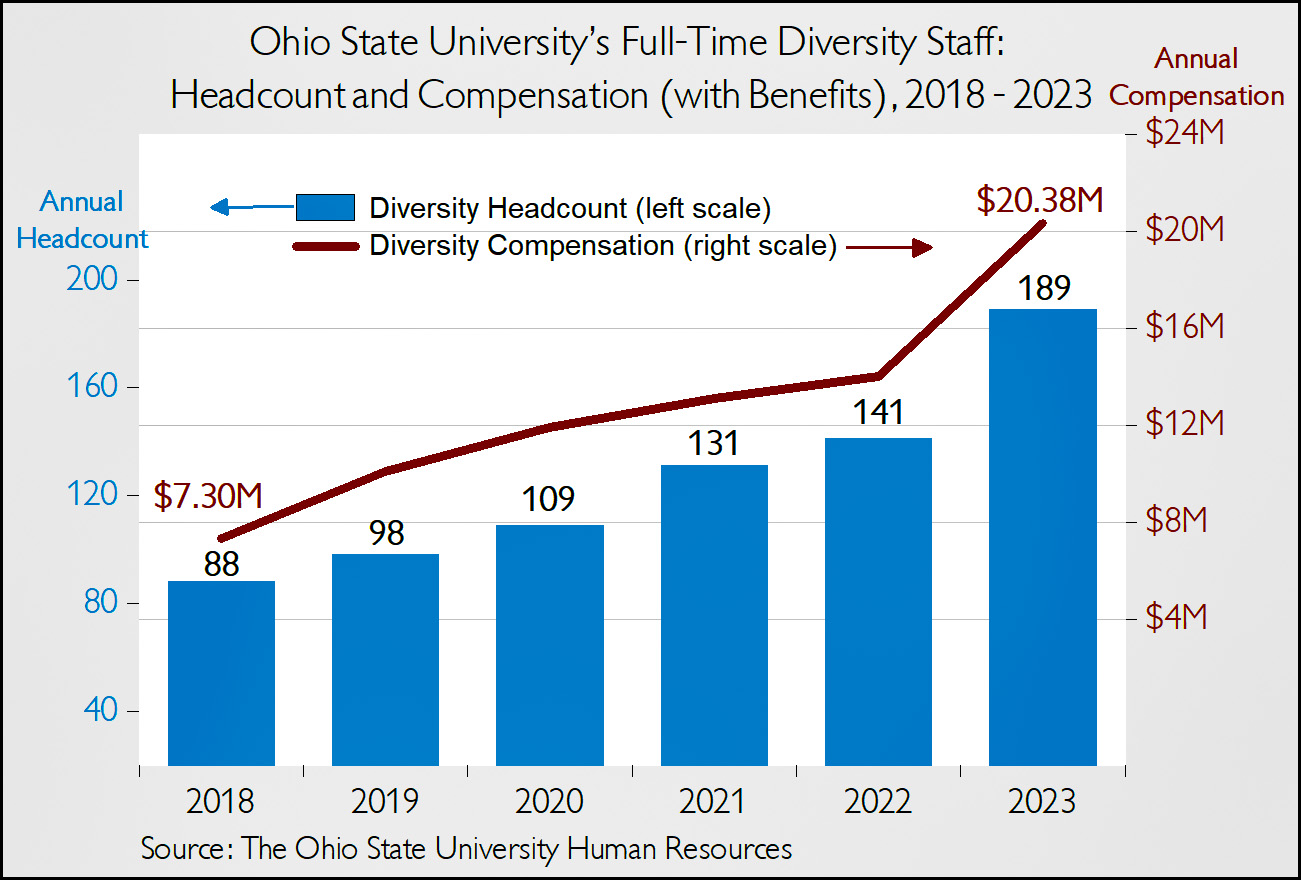

I can't vouch for the accuracy of this, especially since it relied on web searches, but it probably gives a rough idea of things. It's just a snapshot, though, and doesn't show trends. Here's a trend chart for Ohio State University:

I can't vouch for the accuracy of this, especially since it relied on web searches, but it probably gives a rough idea of things. It's just a snapshot, though, and doesn't show trends. Here's a trend chart for Ohio State University:

Put these two things together, stir in the fact that everyone thinks DEI administration has skyrocketed, and it's a pretty good guess that it really has skyrocketed—even more than overall university administration has.

Put these two things together, stir in the fact that everyone thinks DEI administration has skyrocketed, and it's a pretty good guess that it really has skyrocketed—even more than overall university administration has.

Now, it's a little hard to figure out exactly why the right has such a big problem with this. It's not because they care deeply about university budgets, nor is it because this is related to curriculum. These are administrators whose job is mostly to recruit and retain minority students. They claim, of course, that it's just part of their dedication to a colorblind society, but that doesn't really hold water either. So as much as I hate to jump on the racism bandwagon here, it's hard to take this as anything other than general conservative opposition to anything that helps non-white people.

But how about on the left? I have a problem with DEI administration too. Here it is:

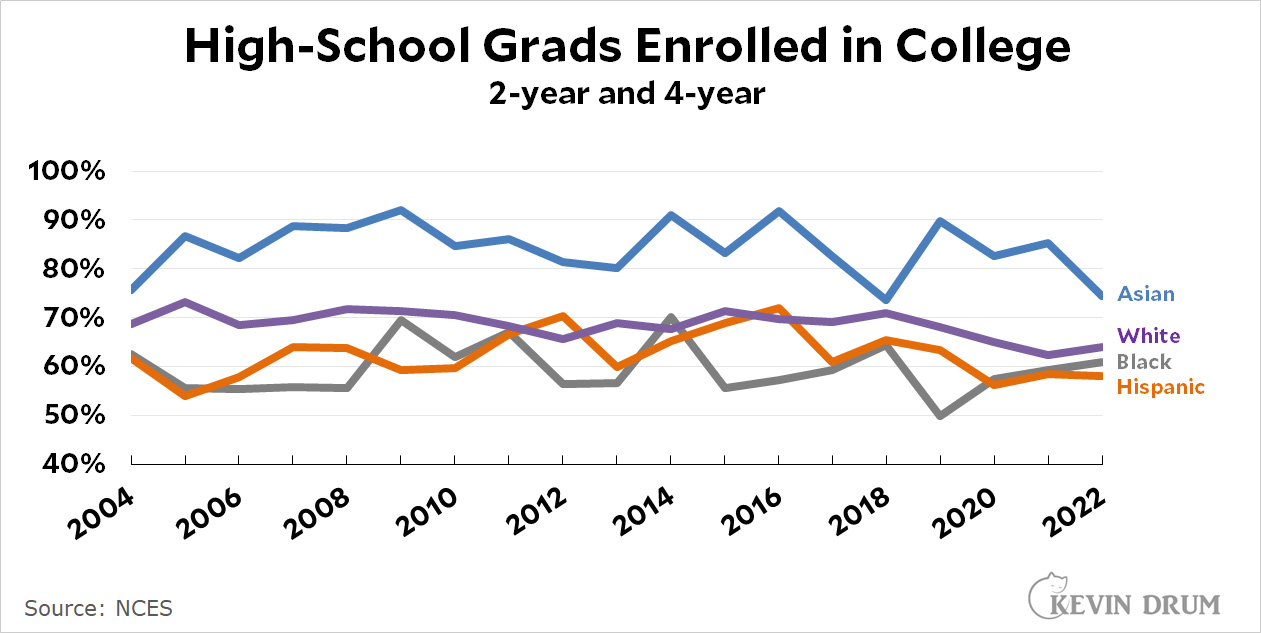

Over the past 20 years DEI programs have expanded considerably but they haven't really accomplished anything. The college enrollment rate of white and Asian students is down slightly while the the enrollment rate of Black and Hispanic students is dead flat.

Over the past 20 years DEI programs have expanded considerably but they haven't really accomplished anything. The college enrollment rate of white and Asian students is down slightly while the the enrollment rate of Black and Hispanic students is dead flat.

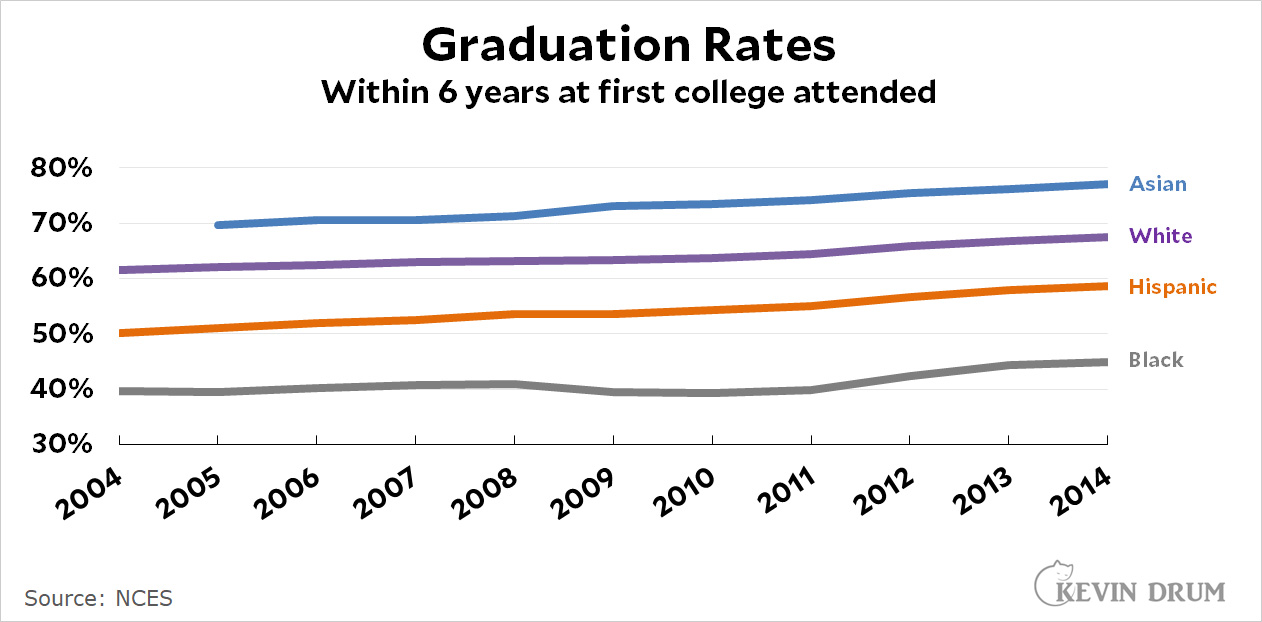

Ditto for graduation rates. They're up for Black and Hispanic students, but no more than they are for everyone else. Universities have apparently gotten better at pushing kids over the finish line, but the Black and Hispanic gap hasn't closed more than a hair.²

So do DEI programs even work? Last night I wrote about the truism that "nothing works," and I suspect this is an example. It's all well intentioned, but what's the point if the end result isn't more students and graduates of color?

¹Soon to be the Power 4, of course.

²The authors of the Heritage report also claim that there's no correlation between a large DEI staff and student satisfaction with the campus DEI climate (among both white and nonwhite students).

Quote of the day: Mickey the slasher

From Mark Lezama, a patent attorney, about recent announcements that Steamboat Willie (aka Mickey Mouse) will be starring in several horror films now that Disney's copyright has expired:

The main thing is to be sure you’re not using Mickey in promotional materials in a way that would make someone think the film came from Disney. I don’t think that should be too hard, especially if Mickey is portrayed as a bloodthirsty sadist.

Lunchtime Photo

What happens if Congress never passes a budget?

Sen. Patty Murray has been sounding alarm bells recently about the possibility of a full-year continuing resolution. This would happen if the House simply gave up on enacting a budget for the current year and instead extended current spending through September.

But there's a catch to a full-year CR: The debt ceiling deal has a provision that says budgets will be cut 1% from 2023 levels if a CR is in effect on January 1. This would take effect in May if no budget has been passed by then.

But then there's another catch: someone has to decide what 2023 levels were and then shave them by 1%. You'd think this would be a black-and-white issue: just look at last year's appropriations bills and add everything up. But no. In practice, the Congressional Budget Office is forced to estimate appropriations levels:

Some bills...name specific amounts....Other bills authorize the appropriation of “such sums as may be necessary”....And still others set forth programmatic directions...that do not explicitly authorize appropriations for those purposes.

In 2022, CBO estimated that nondefense discretionary spending would be $987 billion. At the end of 2023 it recalculated and decided that it had actually been $917 billion. That's a reduction of $70 billion. Add a 1% cut and you have a reduction of $77 billion. This appears to be the amount that Patty Murray is upset about.

I am completely befuddled by this. For starters, every other source puts 2023 spending at $744 billion. This includes the usually reliable Congressional Research Service just a couple of months ago. That's nowhere near either of CBO's estimates.

Second, the CBO's reduction doesn't represent a real reduction. It's merely a new estimate of how much was actually appropriated and spent. A 1% cut would still be 1% from actual 2023 spending levels.

Third, there's a different explanation for Murray's alarm, namely that it involves "side deals" which were part of the debt ceiling talks. Those deals were made by Kevin McCarthy, and Mike Johnson is (allegedly) ignoring them. This amounts to a difference of about $70 billion.

Finally, David Dayen has yet another explanation here, namely that the CR merely has some technical errors that haven't been fixed. But I can't make sense of that either. The CR is a simple, brute force law that says appropriations will continue "at a rate for operations as provided in the applicable appropriations Acts for fiscal year 2023." There's not much room for technical errors, and those errors would only amount to a few billion dollars anyway.

So would a full-year CR really produce enormous cuts to actual spending, as opposed to merely a change in how spending is estimated? I'm confused. If I find a definitive answer, I'll let you know.

Cold feet? Wear socks in bed.

The Wall Street Journal has finally gotten around to addressing one of the great issues of our times:

A growing understanding of the importance of sleep for health and lifespan has made slumber hacks and gadgets all the buzz—including the increasingly common advice to sleep with socks.

....Authorities, from the Cleveland Clinic to the University of Florida Health have expounded on the positives of sleeping in socks.... A study published in the Journal of Physiological Anthropology found that young men fell asleep 7.5 minutes faster, slept 32 minutes longer and woke up 7.5 times less often than those not wearing socks.

First off: the Journal of Physiological Anthropology? wtf does that even mean?

But back to the subject at hand. I've always worn socks to bed for the obvious reason: they keep my feet warm. Marian thinks this is crazy even though she's always complaining that her feet are cold in bed. "Wear socks!" sez I, but she just can't do it.

Neither can I anymore. My chemo treatments have given me a case of peripheral neuropathy, mainly in my feet. This makes it uncomfortable to wear shoes and socks for long periods, and in particular it makes it uncomfortable to wear socks in bed. My choice is either cold feet or maddening neuropathy, and these days I choose the cold feet. It's a sad state of affairs.

But most of you don't have that problem. So if you have cold feet, wear socks in bed! You'll get used to it pretty quickly, especially if you wear cotton socks instead of wool.

Hiring down sharply in November

JOLTS data is out for November and hiring was way down. The number of new hires declined by 363,000, or 6.2%, from October:

Hiring is now down to its 2017 levels. Job openings were also down, but only slightly, and remain well above pre-pandemic levels.

Hiring is now down to its 2017 levels. Job openings were also down, but only slightly, and remain well above pre-pandemic levels.

Nothing works. Now with proof!

It's sort of a truism in the social sciences that nothing works. More specifically, interventions meant to improve things almost never actually do. Megan Stevenson, an economist and criminal justice scholar at the University of Virginia law school, says this about it:

This claim will not be controversial to anyone immersed in the literature. But, like a dirty secret, it almost never gets seriously acknowledged or discussed. Nor is it widely known beyond the small circle of people trained in statistical methods of causal inference. The research that people hear about shows the rare cases of success; the remainder gets filtered from public view.

That's from a newly published article where Stevenson makes two claims about interventions that initially seem successful:

- If you test them with a randomized controlled trial, the gold standard of experimental assessments, they almost always fail.

- If they succeed, they almost always fail when someone tries to replicate them.

Stevenson is focused on the criminal justice space, though she believes her conclusion is probably true for almost all social interventions. The problem is that very often initial successful results get a lot of attention but subsequent failures don't. For example:

In 2017, an article showed that a program teaching youths to “think slow” instead of impulsively responding led to a substantial decline in violent arrests and gains in high school graduation rates.... However, a follow-up article shows that this effect was mostly prevalent in the earliest cohort analyzed: effects for subsequent cohorts were close to zero and statistically insignificant.

....Note that this disappointing follow-up result would be hard to discover. While the original success was published in economics’ most prestigious journal and received widespread media attention, the subsequent failure to replicate is mentioned only tangentially in the back pages of an unpublished working paper on a different topic.

Is Stevenson right that nothing works? I'd say almost certainly—though note that this is only the case for social interventions, not things like vaccines or environmental changes.

Also worth a note: Stevenson points out that plenty of simple, direct interventions work fine. If you give people food, they'll be less hungry. The failures arise for less obvious, more indirect questions. For example, does having more food affect graduation rates or make people less likely to steal stuff?

In any case, Stevenson's claim doesn't have a lot of political valence: it's true for both liberal and conservative interventions. However, by its nature it applies mostly to small-bore interventions, since those are the ones that can be tested. So the good news is that there's still plenty of reason to believe that big, revolutionary changes have plenty of effect.

Lunchtime Photo

Joe Biden has capped insulin prices at $35 per month

CNN is reporting that "all three major insulin manufacturers are offering $35/mo caps on out-of-pocket costs." But that's not really true. They aren't "offering" anything. They fought tooth and nail against this but were essentially forced by Joe Biden to cap their prices via rebate provisions of the American Rescue Plan that would otherwise have cost them hundreds of millions of dollars. Credit where it's due, please.

Starting this week millions more Americans can get cheaper insulin. Never forget that when Democrats capped the price of insulin every single republican in Congress voted no and voted to tell Americans to drop dead. pic.twitter.com/NCxT31ILh6

— Bill Pascrell, Jr. ???????????????? (@BillPascrell) January 2, 2024