Here is Charlie helping perform quality control on the blog.

Lunchtime Photo

Today we have four different photos showing the interior of St. Peter's Basilica. From the top:

- A single frame with the camera turned to portrait mode in order to show more of the floor and ceiling.

- Multiple frames taken from farther back that are stitched together to show a little more floor and ceiling, but considerably more from side to side.

- A cropped version of #2.

- Even more frames stitched together, showing much more ceiling and much more from side to side, but at the expense of additional distortion.

Which one do you like the best?

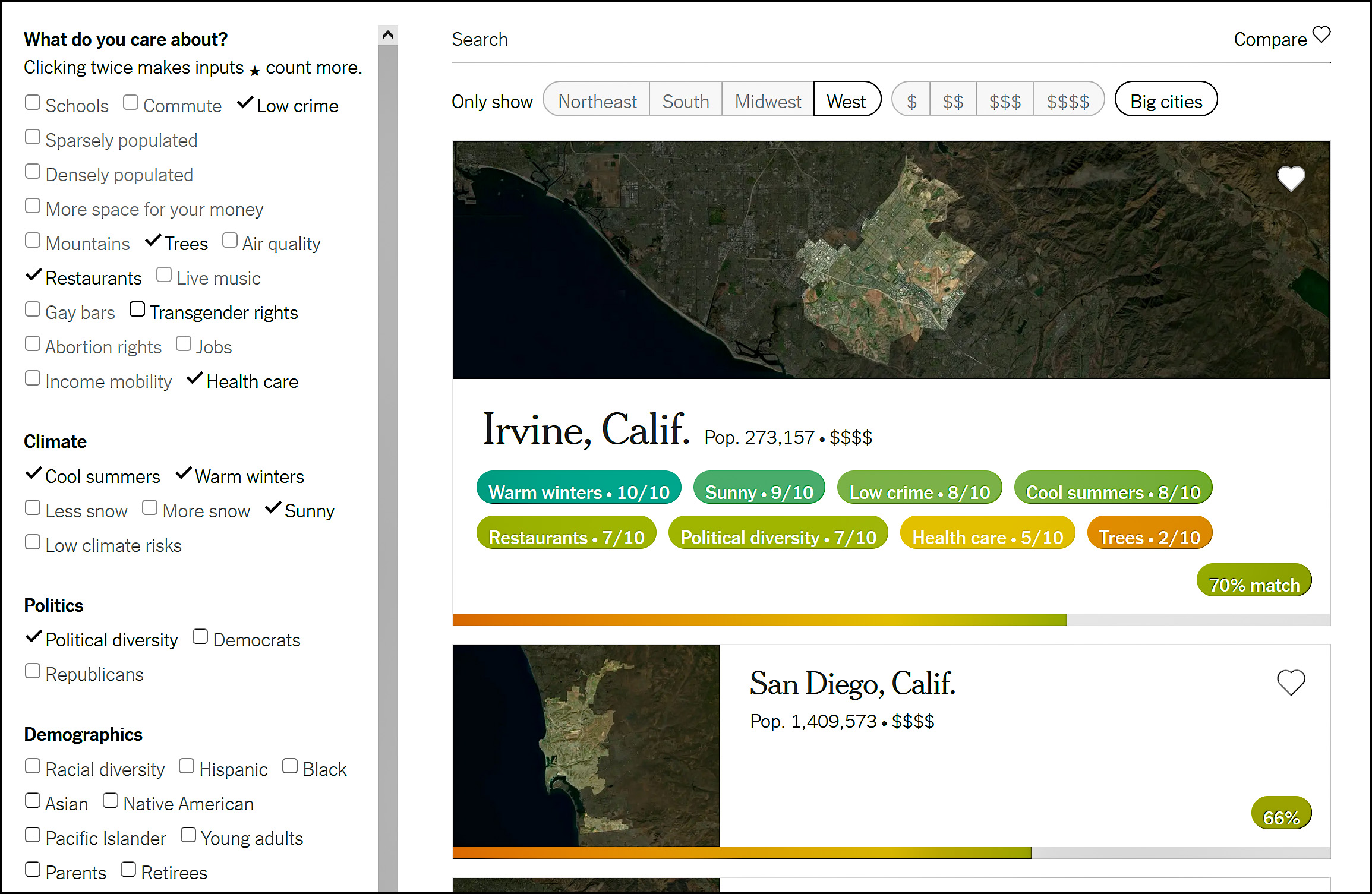

NYT says Irvine is the perfect home for me

It took a bit of doing, but I finally found the set of inputs that provided me with the correct answer on the New York Times's "Where Should You Live" clickbait thingy:

This took a while. At first it kept telling me I should live in New Jersey. Then I restricted it to the West and it told me I should live in various tiny towns in northern California. Then I restricted it to big cities and up popped Irvine. Hooray! Moving is such a pain in the ass.

This took a while. At first it kept telling me I should live in New Jersey. Then I restricted it to the West and it told me I should live in various tiny towns in northern California. Then I restricted it to big cities and up popped Irvine. Hooray! Moving is such a pain in the ass.

Dollar Tree raises prices after 25 years

Oh ffs. Dollar Tree says it is now $1.25 Tree:

The company — one of America's last remaining true dollar stores — said Tuesday it will raise prices from $1 to $1.25 on the majority of its products by the first quarter of 2022. The change is a sign of the pressures low-cost retailers face holding down prices during a period of rising inflation.

I'm whistling into the wind, but I have two comments about this:

- First, Dollar Tree says this is "not a reaction to short-term or transitory market conditions."

- Second, they're right. They've been selling stuff for a dollar since 1993. Prices have nearly doubled since then and it's a miracle that they managed to keep selling stuff for a buck the entire time.

Question: Will our media report things this way? Or will they use this as a hook for "high inflation claims another victim" stories? Sadly, I suspect I know the answer.

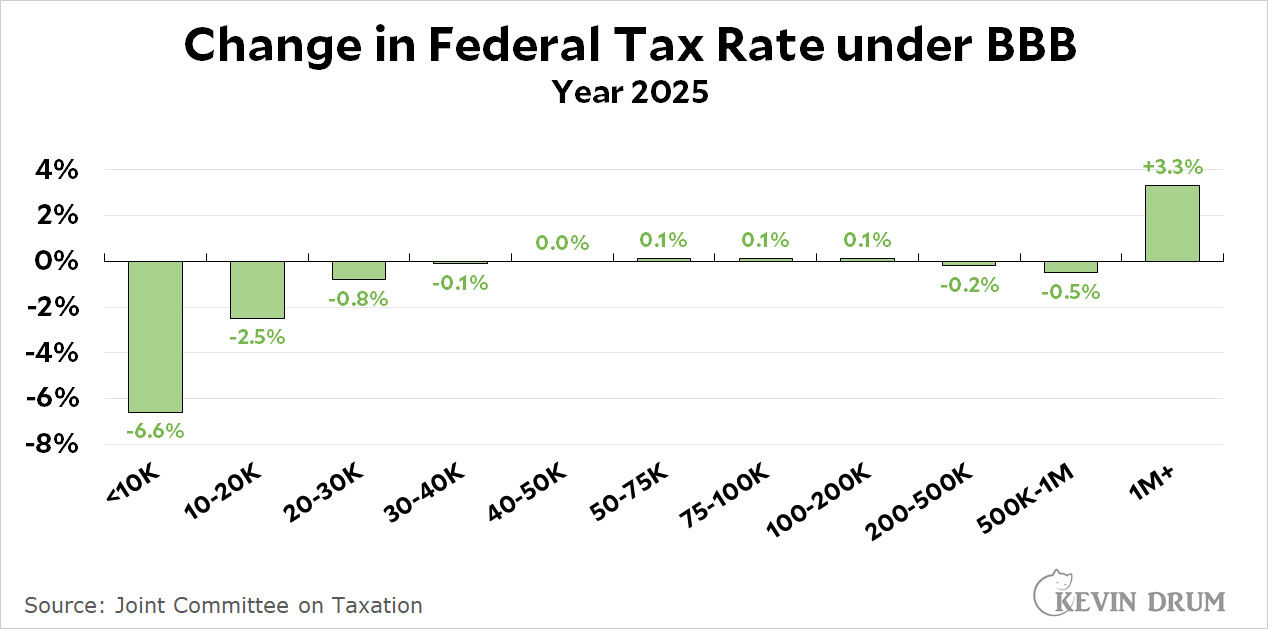

Chart of the day: Federal taxes under the BBB bill

Will you pay higher or lower taxes under Joe Biden's Build Back Better bill? The Joint Tax Committee has the answer:

This is in 2025, when the tax provisions have pretty much all kicked in. It's not clear to me why we want to lower taxes on the $500K crowd, but this is all of a piece with the rest of the bill. It's well intentioned but generally seems to be kind of sloppy in execution.

This is in 2025, when the tax provisions have pretty much all kicked in. It's not clear to me why we want to lower taxes on the $500K crowd, but this is all of a piece with the rest of the bill. It's well intentioned but generally seems to be kind of sloppy in execution.

Are we conducting a “dangerous experiment” on teen girls?

A while ago I asked if there were any academic types who had written a good summary of all the research about the impact of social media on teenage users. At least, I think I did. Maybe I only thought about doing it, because I can't find it now. [Ah, here it is.]

In any case, it turns out that Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge have been compiling a list of research papers on this subject for the past couple of years. This prompted Haidt to write a piece for the Atlantic titled "The Dangerous Experiment on Teen Girls." This article is very specifically about Instagram, not social media in general, and his argument goes approximately like this:

- Gen Z teen girls have been reporting increasingly high rates of anxiety and depression.

- This started happening between 2010-14, exactly the time that Instagram use became nearly universal among teens.

- In a 2017 survey by British researchers, teens rated Instagram as the most harmful of all social media platforms on measures of anxiety, loneliness, body image, and sleep.

- No other explanation for the rise in teen mental health problems makes sense.

By itself, this is not the most persuasive argument I've ever read. However, we can learn more by looking at the Haidt/Twenge list of research papers.

First off, they found 29 studies that showed an association between social media use and teen mental problems. They also found 11 studies showing no association.

This is moderately persuasive, though a 72% hit rate isn't conclusive. A bigger problem is that the studies almost all found that effects kicked in only among teens who used social media a lot (4-5 hours per day or more). This immediately raises the question of whether (a) social media causes mental health problems or (b) teens with mental health problems seek out social media more obsessively.

This is an obvious question, and in a separate section Haidt and Twenge highlight studies designed to test causality. Most of them are experiments where teens are asked to eliminate (or cut back) social media use for a few weeks. At the end of the experiment their mood was compared with that of a control group that made no changes. Of the 13 "true experiments" they found, eight showed a causal effect and five showed no causal effect. This is suggestive, but even less conclusive than the association studies.

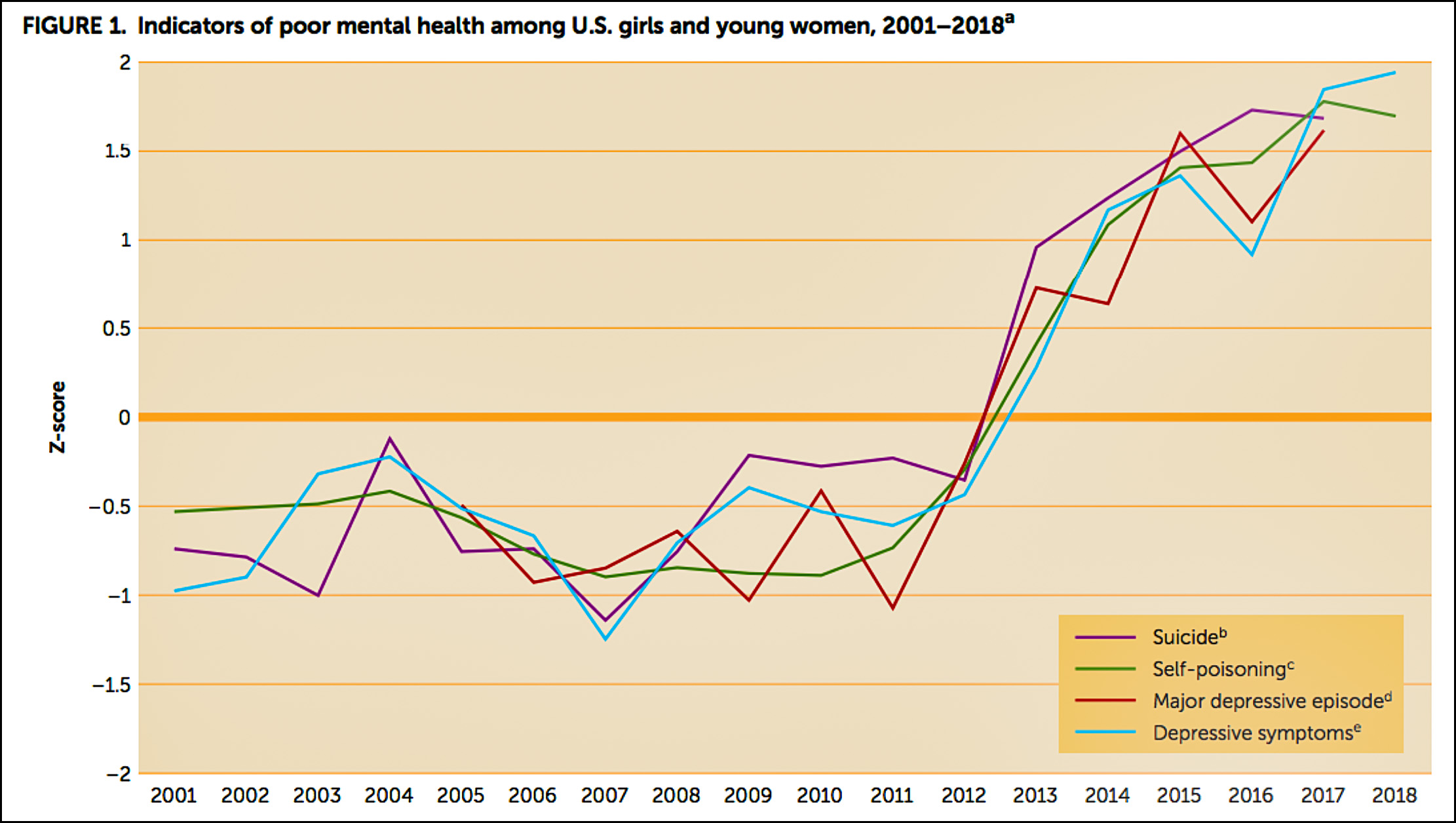

Overall, I'd call this moderately weak evidence. I also had a couple of other problems. This chart, for example:

This shows an astonishing jump in mental health problems between 2011 and 2013. It hardly seems possible that anything could cause such a huge spike in a mere 24 months, and certainly not a mere 10-20 point increase in the number of teens using social media. This makes me wonder if there's some kind of artifact in the reporting of mental health problems.

This shows an astonishing jump in mental health problems between 2011 and 2013. It hardly seems possible that anything could cause such a huge spike in a mere 24 months, and certainly not a mere 10-20 point increase in the number of teens using social media. This makes me wonder if there's some kind of artifact in the reporting of mental health problems.

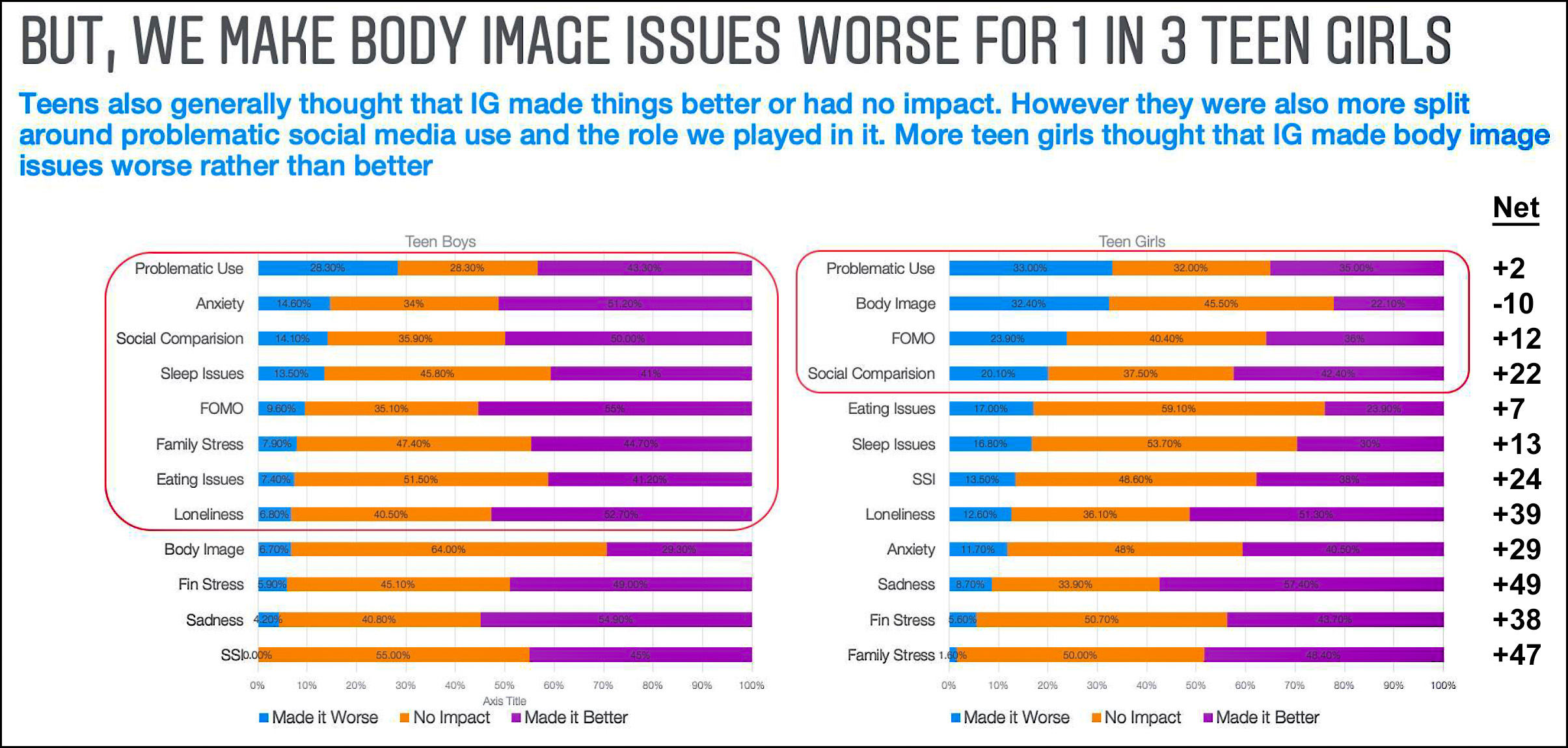

My other problem was Haidt's reference to the recently leaked Facebook documents as support for his thesis. But as I've pointed out before, there's no there there:

Among teen girls, Instagram has a net negative effect on one thing (body image) and a net positive effect on everything else. This simply doesn't support the argument that Instagram is an overall problem for teen girls.

Among teen girls, Instagram has a net negative effect on one thing (body image) and a net positive effect on everything else. This simply doesn't support the argument that Instagram is an overall problem for teen girls.

All this said, there's enough evidence here that it certainly suggests some caution is probably in order. And as it turns out, Haidt makes three proposals that are suitably cautious in turn. First, he wants social media companies to allow academic researchers access to their data. Second, he wants the age of "internet adulthood" to be raised from 13 to 16. Finally, he wants to encourage a norm among parents and schools of delaying use of social media until high school. None of these strike me as objectionable given the suggestive evidence we have.

Obviously research on social media and mental health is difficult to do well. Nevertheless, if we're going to act responsibly instead of moving straight to our usual panic phase, we need something better than what we have now. In particular, we need a more thorough explanation of what happened in the 24 months between 2011 and 2013. Beyond that, we need higher quality studies of how social media affects teens, ideally using something better than self-reported hours of internet use (which is highly unreliable) and self-reported survey questions of mental health (also not terribly reliable). Let's get cracking, researchers!

Yet another gripe about the mythical “trucker shortage”

The Guardian regales us today with yet another article about the shortage of truck drivers:

Truckers say the problem isn’t a shortage of qualified drivers; there’s plenty of people who have been through the training programs and hold a commercial driver’s license. The rot, they say, is far more systemic: low pay, long hours and an industry that treats drivers like “cannon fodder”, churning out new recruits who inevitably quit because the job is so grueling.

“There is no driver shortage; there’s a retention problem,” said Mike Doncaster, a 30-year veteran and driver trainer who parked his big rig at Joe’s Travel Plaza for the night, before heading up to Canada with another load of vegetables.

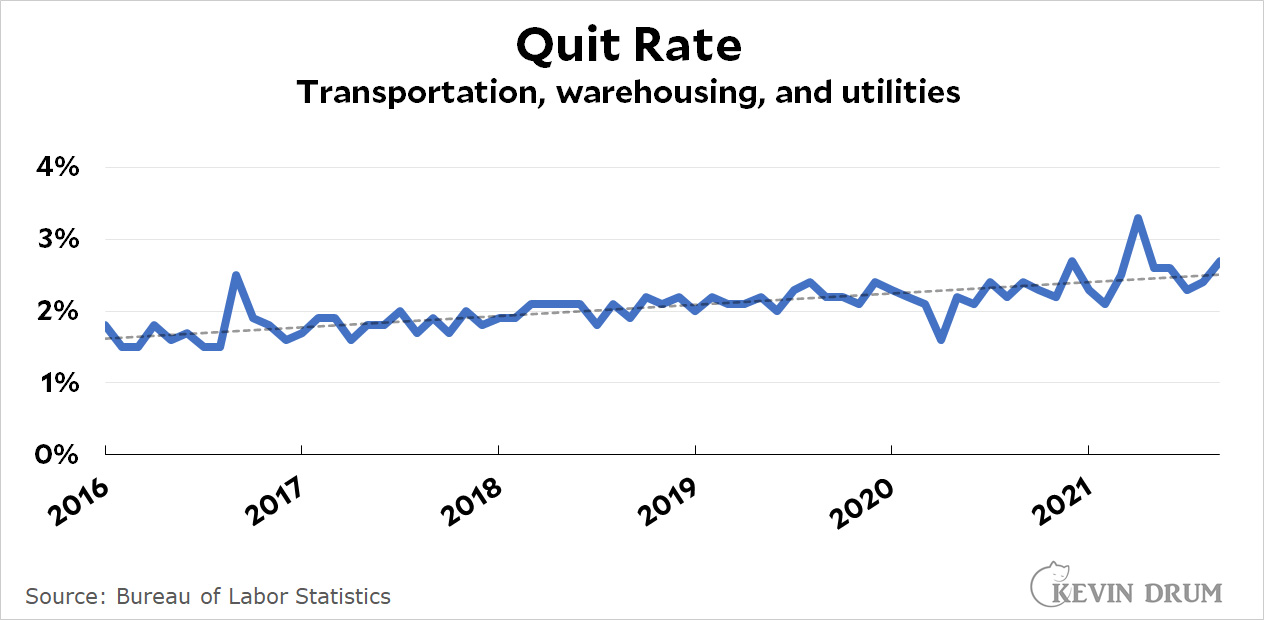

I don't doubt that long-distance trucking is a pretty crappy job these days. But are truckers really quitting at higher rates than usual? Unfortunately, that's hard to say with the data we have at hand. Here's the quit rate:

Nothing looks out of whack in the most recent months, but the data for quits uses pretty broad categories. In this case, it's all transportation, plus warehousing and utility jobs.

Nothing looks out of whack in the most recent months, but the data for quits uses pretty broad categories. In this case, it's all transportation, plus warehousing and utility jobs.

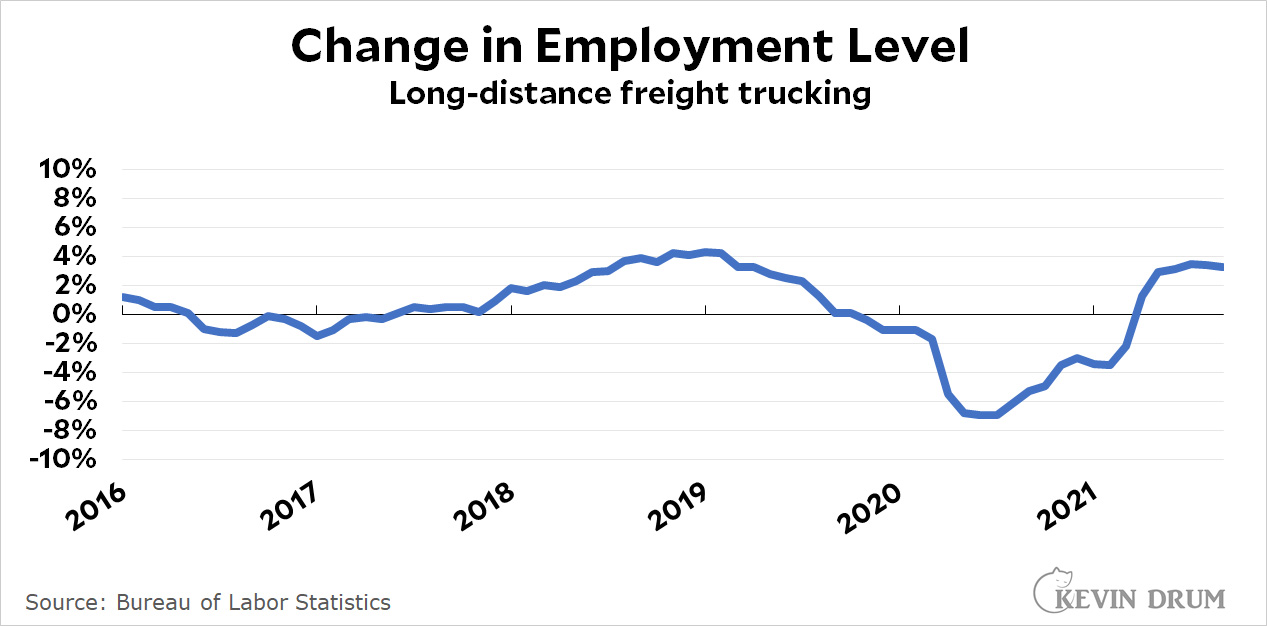

We also have this:

The absolute number of long-distance truckers is within a percent or two of where it was before the pandemic, and employment is rising at a rate of more than 3%.

The absolute number of long-distance truckers is within a percent or two of where it was before the pandemic, and employment is rising at a rate of more than 3%.

So we have one series that shows quits, but only broadly, and another that zeroes in on long-distance drivers but only shows employment levels. If you put them together I think the obvious interpretation is that nothing new is happening right now. Quits are probably no higher than historic levels, and the number of drivers is increasing solidly. What's more, long-distance driving continues to pay about 25% better than other blue-collar jobs.

To put things simply, we don't have a trucker shortage, we have a goods surplus. In an economic sense I suppose you can say they're the same thing, but given that the goods surplus is almost certainly temporary it hardly seems likely that trucking firms want to hire a lot more permanent drivers who they won't need six months from now. They're hiring as many truckers as they think they need and they don't seem to be having a lot of trouble attracting them.

What’s behind Joe Biden’s low approval rating?

Why is Joe Biden so unpopular? As the pundits stroke their chins and come up with ever more abstruse theories, allow me to butt in. We should all know by now that normal political polls of "the public" are all but useless in these polarized times. You have to look at Democrats and Republicans separately to make any sense out of anything. Here's what Biden's approval rating really looks like these days:

Roughly speaking, support among Democratic and Republican partisans went down by a modest six points during Biden's first few months and then flattened out. Since about midsummer, their support hasn't fluctuated more than a point or two.

Roughly speaking, support among Democratic and Republican partisans went down by a modest six points during Biden's first few months and then flattened out. Since about midsummer, their support hasn't fluctuated more than a point or two.

In other words, all the stuff that happened after the middle of summer—Afghanistan, inflation, CRT, the infrastructure bill passing, the social spending bill not passing—has had essentially no impact on partisans.

But then there are independents. Their support went down 13 points through midsummer and then kept on dropping, losing another 11 points through November. What's going on with them? All the usual suspects might explain what happened after midsummer, but independents also soured on Biden very strongly in the months before midsummer, when none of this stuff had yet happened.

So that's the mystery. Why has Biden lost a whopping 24 points of support among independents? For this, we have to abandon our usual way of thinking and pretend to be the kind of people who don't pay much attention to politics. They don't know what Tucker Carlson said last night. They don't know that Republicans are refusing subpoenas to testify before Congress. They don't know what's so great about the infrastructure bill, and are probably totally unaware of what's in the social spending bill. Generally speaking, they aren't especially outraged by anything going on in Washington DC.

So what's been eating at them for the past ten months? You probably think that this is the point at which I unveil my brilliant analysis, but I don't know any more than you do. My only real guess is that it's less connected to politics than we political junkies like to think.

The most obvious candidate is the seemingly endless COVID-19 pandemic. Ditto for the related turmoil over remote school, which is a huge issue for parents with young children.

On the other hand, it's probably not the economy: the unemployment rate is low and nominal blue-collar wages have been rising steadily over the past year. Inflation is an issue, but only over the past couple of months.

Cars have been a problem. The price of new cars and trucks has gone up amid continuing shortages, while the price of used cars and trucks has skyrocketed.

What else is bugging people? Give this a real try without resorting to political effluvia. Just ordinary, everyday problems that have gotten more and more tiresome over the past year with Biden seemingly unable or unwilling to do anything about them. Ideas?

Lunchtime Photo

This is the Atchafalaya Swamp, just up the road from Lafayette. You can see the distinct water line on the tree trunks, which shows how high the water level gets in spring. These are mostly new-growth cypress trees, the old-growth trees having long ago been cut down to feed the maws of northern factories.

We are nowhere near herd immunity for COVID-19

The LA Times says that Colorado may hold a lesson for California:

California is entering the holiday season with an uncertain outlook. Optimistically, new weekly coronavirus cases have become stable statewide; the vaccination rate is higher than in many other states, and there are few signs right now of a big winter surge.

But the deteriorating conditions in Colorado offer a cautionary tale of how things can go south quickly....In Colorado, 62.8% of all residents are fully vaccinated, almost identical to California’s 62.7%, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But the differences in weekly case rates are stark: CDC data show California currently has the 10th lowest out of all states, and Colorado has the eighth highest.

It's worth remembering that researchers long ago changed their estimates of herd immunity from 60-70% of the population being vaccinated to 90+% of the population—including children—being vaccinated. Obviously more vaccination is better than less, but as long as we remain well below 90% we should expect that we will continue to suffer periodic outbreaks. Colorado is having one now, and there's little reason to think that California or any other state will avoid one over the next few months.

POSTSCRIPT: Why the change in estimates of what it takes to reach herd immunity? Part of it was the introduction of the Delta variant. Part of it is the fact that our vaccines appear to get less effective over time. And part of it is better modeling of vaccines—like the ones we have—that don't prevent viral transmission.

ANOTHER POSTSCRIPT: Yes, this means that we will probably never eliminate COVID-19 via herd immunity. We can manage COVID-19, but it's likely to eventually become endemic, like the flu.