In news that comes as a shock to everyone who hasn't actually been paying attention, evictions haven't skyrocketed since the eviction moratorium ended last month:

In major metropolitan areas, the number of eviction filings has dropped or remained flat since the Supreme Court struck down the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium on Aug. 26, according to experts and data collected by the Eviction Lab at Princeton University. In cities around the country, including Cleveland, Memphis, Charleston and Indianapolis, eviction filings are well below their pre-pandemic levels.

....The overall picture has confused experts who had grim warnings for the looming crisis once the federal ban was no longer in place. Those same experts are hesitant to say the wave won’t come. After all, recent Pulse Survey data by the Census Bureau suggests that some 3 million households have reported concerns of imminent eviction.

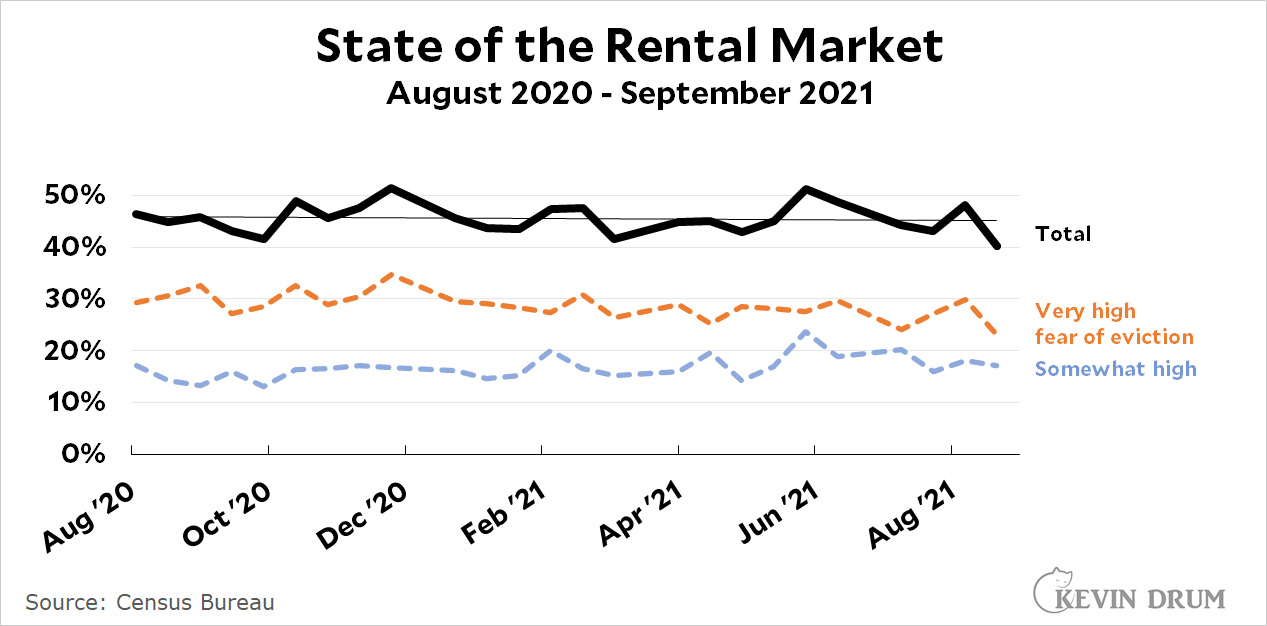

Yes, the Household Pulse survey suggests that about 3 million families fear that they may be evicted in the next couple of months. However, this is a pretty worthless statistic. First, it includes only families that are renting homes, not apartments. Second, it's based on the number of people surveyed, which changes from week to week. Third, what we want to know is not the raw number anyway, but whether it's going up or down as a percentage of all home renters. Here's the answer:

I wouldn't take this very seriously, but just for the record it shows that fear of eviction has been pretty stable for the past year and actually dipped a bit at the end of September.

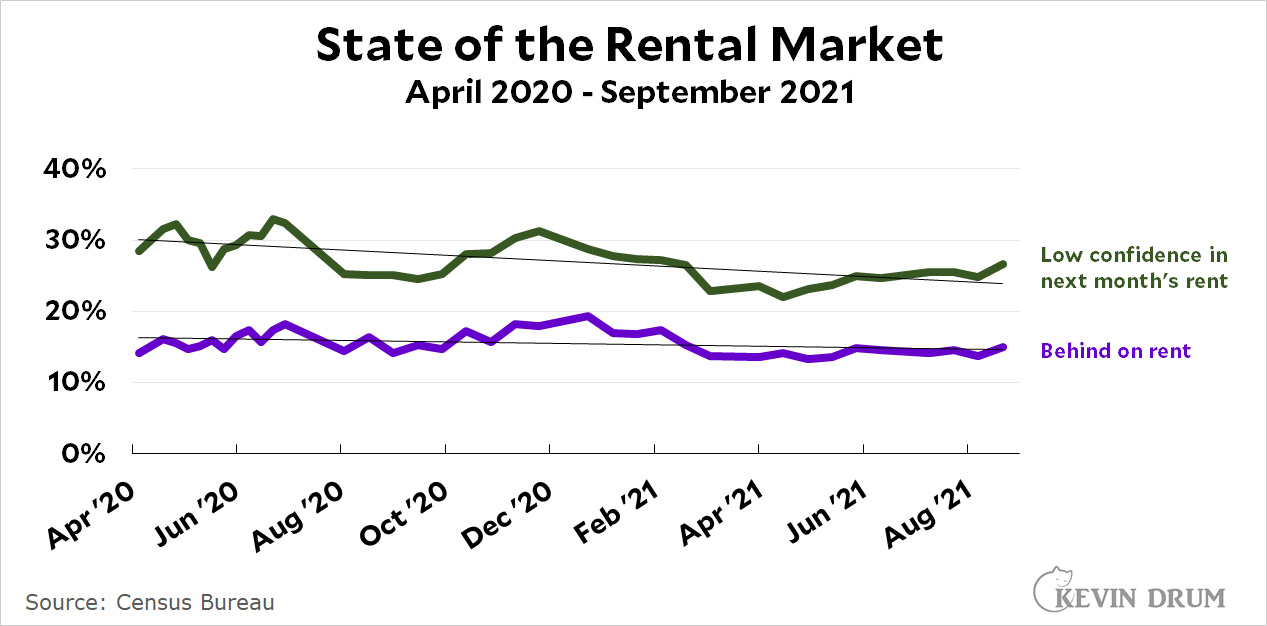

Here's a better set of data from the survey:

This includes all renters and goes back further than the eviction question. It shows that trouble making rent has trended generally downward, but with a small blip upward at the end of September. Is that meaningful? It's too early to say. The next release of the Household Pulse survey will give us our first true look at things in the weeks following the end of the rent moratorium.

In any case, there's no mystery here. The reason that evictions aren't skyrocketing is because the rescue packages passed by Congress kept poor people whole during the pandemic and even allowed them to save a little. Those benefits have now ended, but people are mostly as current on their rent as usual and are now back to where they started before the recession. There's really no special reason why they should be any farther behind on rent than they've ever been.

It's striking to me that this isn't more widely recognized. The big pandemic rescue packages were a victory for liberals, and we should be celebrating the fact that they allowed low-income workers to survive the pandemic recession mostly intact. The rent figures are pretty good evidence that we did the right thing.

The obvious problem with this is that you lose the absolute numbers, which are often handy to have. But perhaps you gain clarity?

The obvious problem with this is that you lose the absolute numbers, which are often handy to have. But perhaps you gain clarity?