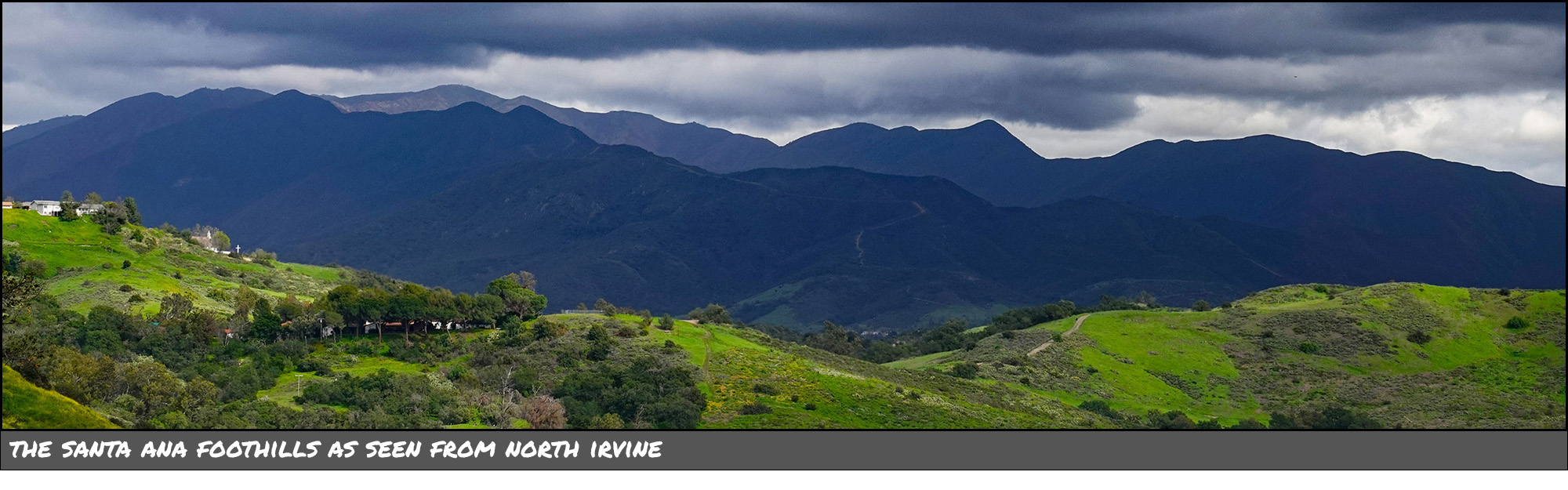

Matt Yglesias linked to an old piece of his about homelessness today, and that reminded me of a conversation I had a few days ago. I was telling a friend that homelessness is mainly a reflection of high housing costs, which is why Los Angeles has such a high homeless rate. OK, he said, but what about Irvine? Housing is expensive in Irvine too.

And that's true. But income is also high in Irvine, and it's average rent as a share of average income that's the real driver of homelessness. Here's a chart from a paper written by a team of researchers a couple of years ago:

Needless to say, there are lots of things that affect the homelessness rate. The cost of rent is only part of the story, which is why LA and Irvine are both off the trendline a bit.¹ Nevertheless, the trend is clear: As rent goes up as a percent of income, homelessness goes up. When it passes 32%, homelessness goes up really fast. This is the state of affairs in lots of big cities.

So what's the answer? To a certain extent, there isn't one in the short term. As long as housing costs are high, you're going to be stuck with lots of homeless people. And as we all know, the most common view of homelessness is (a) we should build more shelter (b) somewhere else.

Oddly, though, there is a partial answer, but it's one that's largely ignored. It's called Housing First, and it has two parts. The first part, which everyone understands, is to build permanent housing. The second part, which gets a lot less attention, is to skip all the rules to qualify for this housing. Just let people in, regardless of whether they have drinking problems, or drug problems, or need mental health treatment. Just let them in.²

You see, it turns out that a big part of the problem with getting the homeless into homes is that many of them would rather be in a tent on the street than in an apartment with lots of rules. So skip the rules. Surprisingly, to many people, this doesn't cause a lot of problems.

Another thing is to stop whining about the cost of cheap housing. It's true, for example, that the cost of a trailer or a tiny home or a plexiglass dome is fairly modest, running maybe $10-20,000 apiece. But you have to put it somewhere, and an acre of land in central Los Angeles will run you $5-10 million. Then add in the fact that you need some security, and maybe showers and food depending on your goals, and you're up to $500,000 per shelter. That's outrageous! Maybe, but that's how things are in a big city.

Based on my (limited) experience, I'm all in favor of this. The problem, as always, is that no matter what kind of shelter you're talking about, no one wants a bunch of homeless near their neighborhood. And there's no way to finesse this. All it takes is one person to start a lawsuit and you'll chew up years of time. This is by far the most fundamental problem facing projects to build housing for the homeless, and no one seems to have a serious answer to it. I certainly don't.

¹There's also politics involved. Irvine, for example, has been accused for years of picking up its homeless and dumping them in nearby Santa Ana. This is something that smallish cities can do but bigger cities can't.

²Obviously this doesn't account for everyone. Some homeless people, especially those with families, very much want a normal apartment while they try to get back on their feet. Not only are they willing to follow rules, they prefer a place where everyone else follows some rules too.

At the other end of the spectrum, some people will resist assistance no matter what. That's a very tough nut to crack.