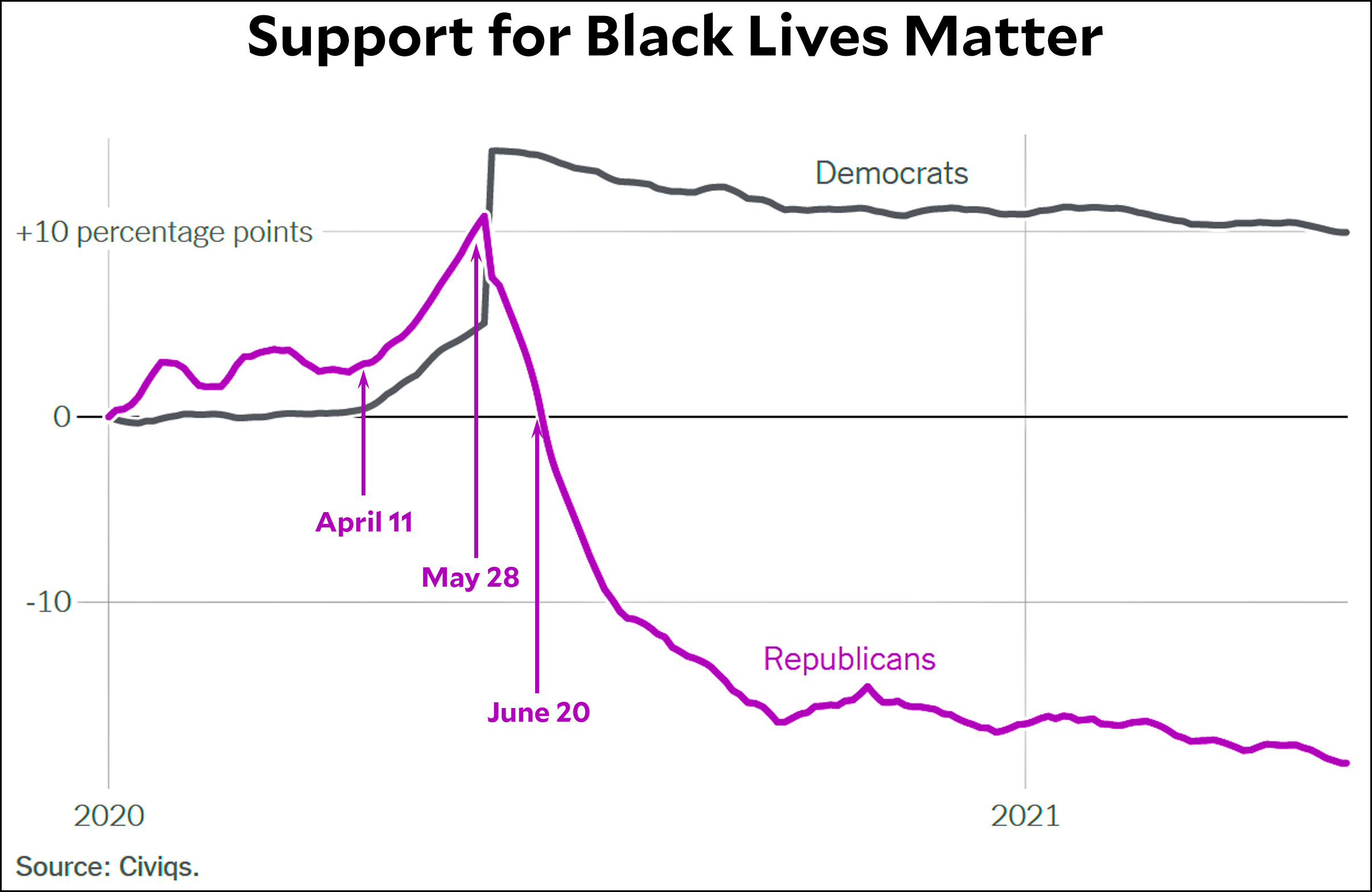

The New York Times published an interesting essay today that includes a chart showing support for Black Lives Matter in the wake of the George Floyd murder. But it's even more interesting if you put some dates on the chart:

Support for BLM starts to increase within both parties at the beginning of April, following a couple of lower-profile police killings. George Floyd was killed on May 25, and that's when support for BLM hits its peak.

But within three weeks, Republican support has plummeted to its level at the beginning of the year, and by autumn it's another 15 points lower. Democratic support also wanes, but only a little bit.

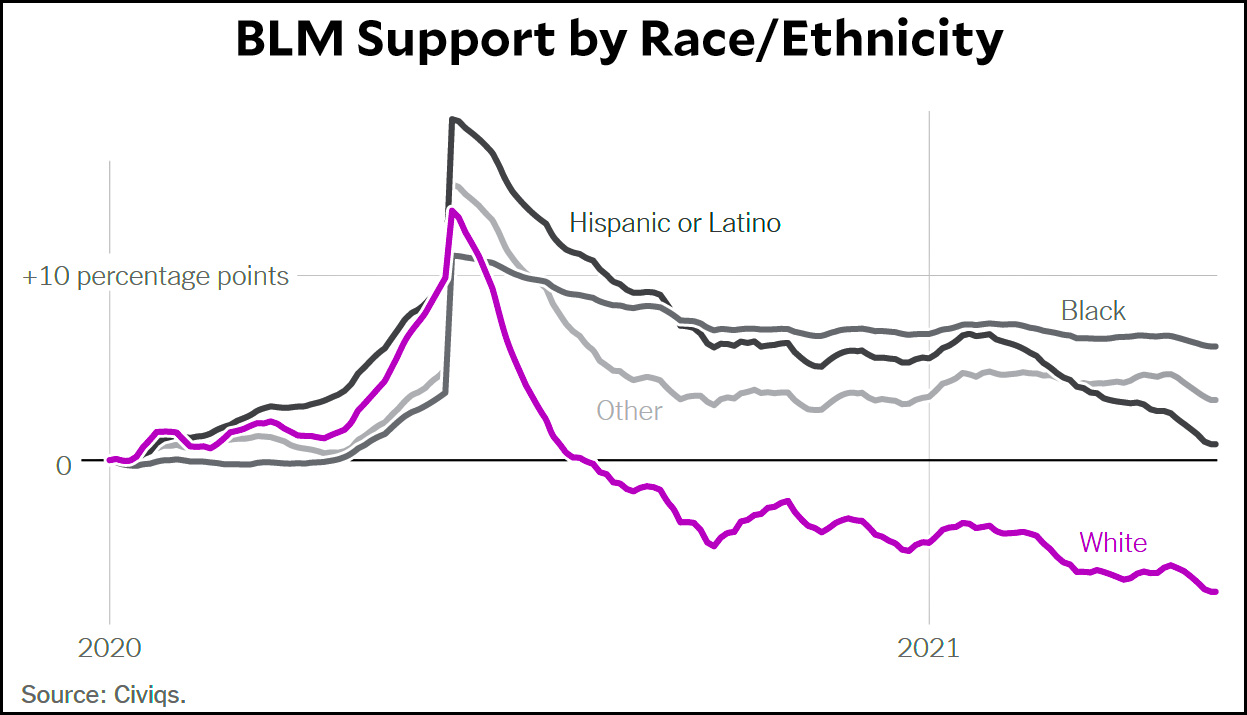

As you'd expect, since Republicans are mostly white while Democrats have a large Black contingent, white support for BLM went down sharply after the George Floyd murder while Black support went down only a little. Without further crosstabs, it's hard to say whether race or party ID is the most important factor here.

I remember writing something a couple of months after the George Floyd murder about BLM having a "moment." I got some editorial pushback on that and revised it. But compared to support for BLM right before the George Floyd murder, the BLM protests of last summer produced:

- A huge decline in BLM support among white people.

- A big decline in support among Hispanics.

- A modest decline among "Other."

- A modest increase in support among Black people.

Even among Black respondents, who registered an eight-point spike immediately after the George Floyd murder, support for BLM by the end of the year was only about two points higher than it was just before the George Floyd murder.

It's pretty obvious that the massive downturn among Republicans is due largely to Fox News and its cronies. But every other group also ended the year with less support for BLM than it had before the protests. The only exception is among Black people, and even that's a close call.

So a moment it was. The question now is how to turn it into more than that.