Harvesting the strawberry crop on May Day.

Cats, charts, and politics

Harvesting the strawberry crop on May Day.

There are certain topics that generate an almost infinite number of news articles that are essentially identical except for the single detail of who the main character is. The pandemic is an example: you can write a piece about how it affected the theater business; and the restaurant business; and the trucking industry; and Joe's Dry Cleaning—and they will all be basically the same: their customers went away and this caused them big problems. Racism works the same way: you can write a thousand stories about a thousand different industries and they're essentially all identical. The details will differ, but it will turn out that racism is responsible for the underrepresentation of Black/Hispanic/Female/etc. people in that industry.

We are now entering the same phase of the end-of-lockdown pandemic story. Guess what? It turns out that practically every industry cut back on production because their customers stopped buying stuff. And only now, for reasons that remain puzzling, are they realizing that the pandemic wasn't a permanent condition and they need to ramp up production. Why didn't they figure this out a few months ago when vaccines became widely available? Beats me. My unconsidered view is that it's because they're idiots, but I suppose there's more to it.

Anyway, we're now being deluged with stories along this line. Last night, for example, 60 Minutes ran a segment about the shortage of chips for cars and videogames and whatnot. And why is there a shortage of chips? Is it because we've outsourced everything to the wily Chinese folks on Taiwan? You'd think so after inhaling Lesley Stahl's inane reporting, except for the fact that she inadvertently allowed the chairman of Taiwanese chipmaker TSMC a brief moment to give the game away: "In March, 2020, as COVID paralyzed the U.S., car sales tumbled, leading automakers to cancel their chip orders. So TSMC stopped making them."

Oh. So it has nothing to do with Taiwanese fabs vs. American fabs or global supply constraints or any of that. Nor is it related to a possible invasion of Taiwan or the fact that Intel may or may not have made good decisions about its future business. It's because American car companies canceled their chip orders and never bothered to reinstate them. Then in December, when car sales "unexpectedly" began to rebound, they panicked and realized what they had done. You'd think these guys had never done an economic forecast or used an MRP system before in their lives.

Anyway, be prepared for hundreds of stories like this. For each one, be careful to ignore the details and instead focus on the big picture. In about 90% of them, it will be the same: They didn't plan for the pandemic to ever end, and now they're paying the price.

If you sell an app for use on an iPhone, Apple demands a 30% cut of any revenue generated by the app. But is this legal?

Apple is being sued by Epic, the maker of the popular video game “Fortnite,” for allegedly using its control of its mobile operating system to stymie competition....Up for debate is how Apple allows apps to function on iPhones. The only way to install software on Apple’s mobile operating system, called iOS, is through the company’s App Store. Developers who make software for iOS must follow Apple’s rules and use its payment system, which charges a commission on every sale.

....The trial will determine whether Apple’s control over iOS is a monopoly, and whether Apple can use that control to force developers to use the App Store and its payment system. One possible outcome in the case is a very different smartphone landscape, in which the powerful computers in everyone’s pockets operate more like desktop computers, where any kind of software is allowed to exist.

The trial begins today. As it happens, Apple's market share of smartphones in the United States is about 50%. Does that qualify as a monopoly? I'm not sure, but it comes pretty close by anyone's measure.¹

One thing to keep in mind, because a lot of people don't seem to understand this, is that there's no law against being big. Nor is there any law against having a huge market share. Like it or not, though, there is a law that prevents big companies from abusing their bigness. A small company could charge anything it wanted to sell apps on its phones and no one would have a case against them. But a big company has to be more careful. There are things a small company can do that a big company can't.

So the question is whether Apple is doing something that they shouldn't, even if it's something that a smaller company could get away with. But the peculiar thing about this case is that antitrust law is generally oriented toward preventing big companies from doing things that stifle competition. Spotify, for example, says that Apple's 30% charge makes it hard for them to compete against Apple's own music offerings. That's a fairly normal case.

But Epic is different. Even if they can show that Apple has a habit of stifling competition in some cases, Apple doesn't have a big presence in the gaming market and their 30% charge doesn't really do much to prevent competition against Apple's own offerings. It's just a way of hoovering up a bunch of money. So even if Apple is, in some sense, abusing its bigness, it doesn't seem like it's doing anything that makes it harder for small gaming companies to enter the market.

In any case, this trial is scheduled to last three weeks plus about a thousand years of appeals, so don't expect any quick decisions. Normally, I might predict that the companies will reach a settlement before then, but both CEOs seem inclined to treat this as something of a dick-measuring contest and are unlikely to give up. So this case might truly drag on nearly forever.

It's more than obvious now that early April represented our peak vaccination rate and we're now declining pretty steadily.

This whole thing is just such an ungodly shame. For all the endless griping about how badly we screwed up our response to the pandemic, nobody can complain about our vaccine development. The Chinese released the coronavirus genome on January 10; we had the first vaccines developed by January 12; and they were ready for distribution by December. That's just mind-boggling. Overall, we've also done a good job of distributing them, with something like half the country vaccinated within four months.

But now, just as we're on the brink of truly crushing the coronavirus, we can't quite take the final step. Masking and other countermeasures are being abandoned too quickly and we're now having trouble getting the other half of the country to get the vaccine. All we need is a few more weeks. That's it. And we can't quite do it.

We'll get there eventually. Everyone forgets this now, but vaccine hesitancy ran around 30% for the polio vaccine too, so response to the coronavirus vaccine is not unprecedented. I'm just not sure if that makes me feel any better.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 2. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

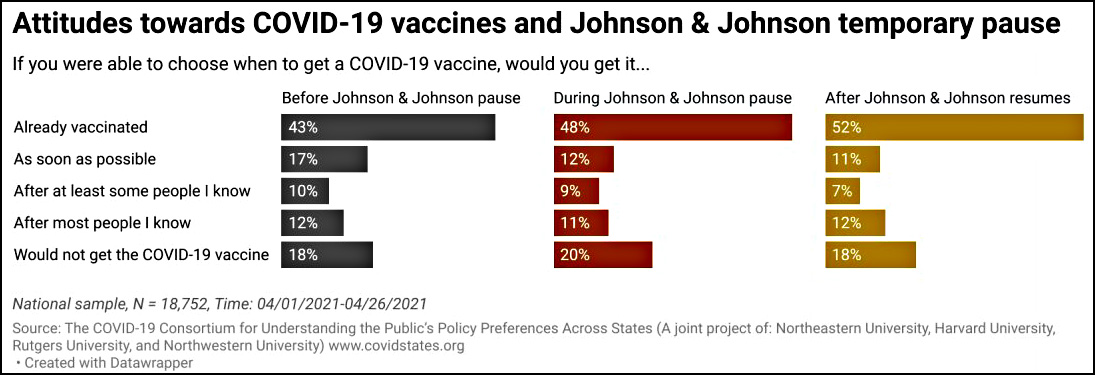

A new study suggests that the CDC's pause in administering the Johnson & Johnson vaccine had little to no effect on attitudes toward vaccination. Here are the results of a survey that spans before, during, and after the pause:

Before the pause, 60% of the respondents had either gotten vaccinated or wanted to as soon as possible. After the pause, that number was 63%. The percentage who wanted to wait until "after most people I know" stayed the same, as did the number of people who flatly didn't want it.

The authors also break down the results by demographic group, and there's not a single group that's more vaccine hesitant after the pause. Their conclusion:

Our survey suggests that awareness of the J&J pause was extremely high. Despite this, vaccine hesitancy/resistance did not increase for responses received after the pause, and our analysis of repeat respondents suggests a small but systematic shift decrease, largely because a fair number of people who were vaccine hesitant in early April were vaccinated by late April. In short, it seems very unlikely that the pause had major negative effects on vaccine attitudes.

My update to Wednesday's post about the J&J pause points in the same direction. The immediate decline in vaccination rates after the pause was due mostly to a decline in J&J vaccines, as you'd expect, and the subsequent smaller decline in the overall vaccination rate was most likely because we had vaccinated nearly everyone who was enthusiastic and were now entering a new phase that required more work to persuade people to get shots.

For now, then, I've changed my mind. It appears as if the J&J pause, regardless of whether it was right or wrong, probably had little to no effect on vaccine resistance.

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through May 1. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

I keep going back and forth:

I dunno. I get tired of the folks who make a big deal out of masks, but I also get tired of the immense weenie-ness of a big chunk of the American public. Maybe I'm just tired, period.

My monthly M-protein numbers are in for April. They're up a little bit, but not by much:

In other news, I had a sudden insight a couple of days ago about my longtime breathing problem.

Readers with good memories will recall that this all started in 2013, after I tripped and fell on my chest. My breathing worsened over the next few months until it got to the point that I was gasping for breath just sitting down. I ended up in the ER, followed by a battery of tests from a pulmonologist which revealed nothing. In retrospect, I'm pretty sure that the cause was a couple of broken ribs that went undetected and which I aggravated over time.

My breathing improved steadily after that, but then I was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and went through several months of chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant. Those caused lots of fatigue and all of my health problems sort of blended together after that. My breathing problem had improved enough that it was still mild after the initial chemo was finished, but it got steadily worse over the years until recently, when it's become pretty bad.

Except for one thing: I don't have a breathing problem. I can breathe deeply and fully. I've been thinking of it as a breathing problem only because it started out that way and because even a small amount of exertion does cause me to breathe pretty heavily. But that's not a breathing problem, it's a stamina problem. And loss of stamina is a common side effect of cancer meds. Every single one I've taken—velcade, revlimid, darzalex, dex, and now pomalyst—warns of this. It is probably the most common side effect of cancer and cancer meds.

For some reason it took me five years to figure this out, but then again, none of my oncologists has suggested it either. So I guess I shouldn't feel too bad. In any case, what this means is that I can stop wondering what's going on with my breathing and instead accept that stamina deterioration is a pretty standard part of chemo meds that, unfortunately, has no remedy. That won't make me any better, but at least I can stop wondering what the hell is going on.

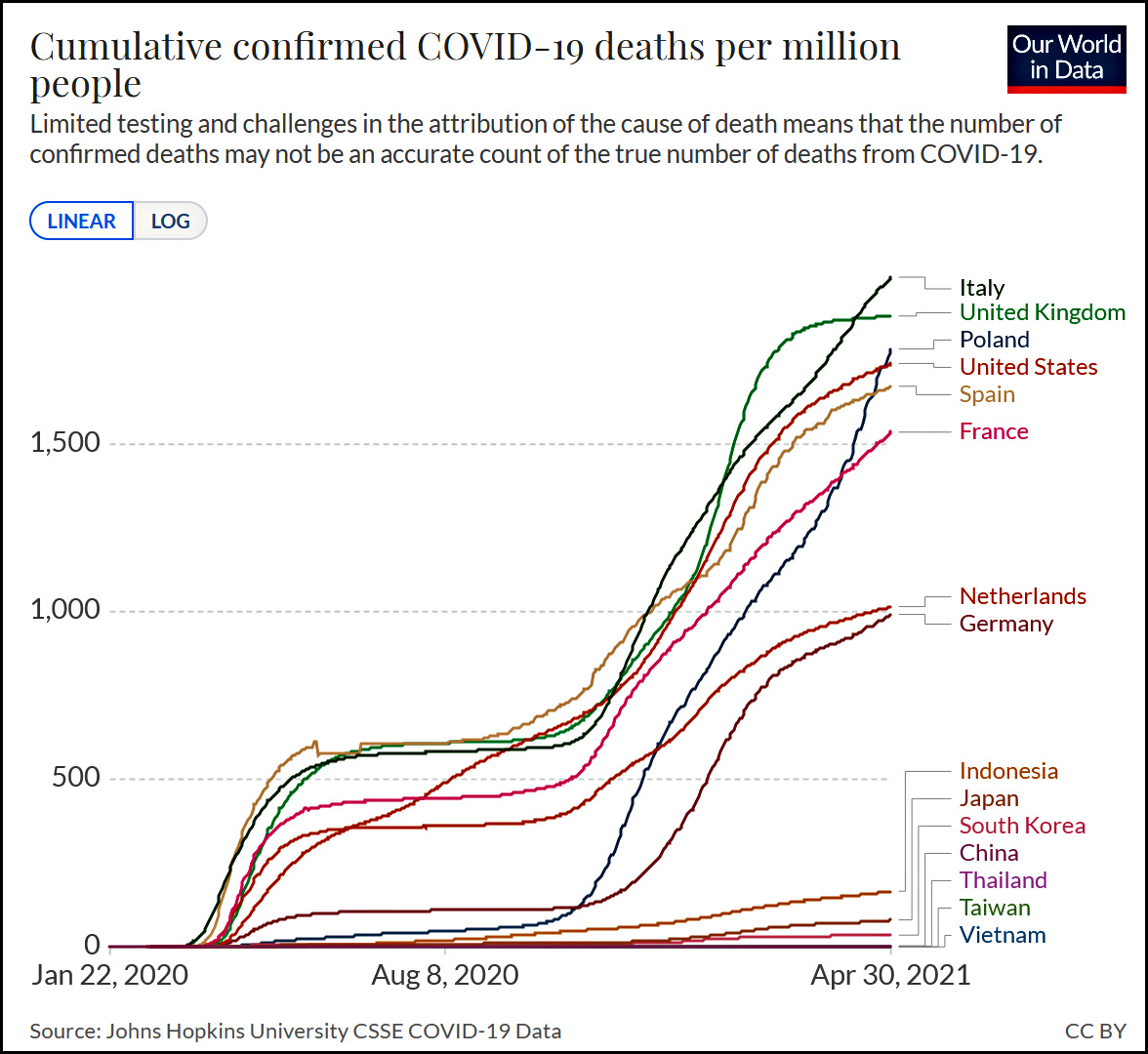

A friend emails to ask why I don't include, say, Japan, in my daily roundup of COVID-19 mortality. The answer is pretty simple:

This is not every European country or every Asian country, but it gives a pretty good representation of what's going on. Basically, nearly all European countries (plus the US) have very high COVID-19 death rates and nearly all Asian countries have very low rates. Taken as a whole, the mortality rate in Europe is 14x the mortality rate in Asia. This is the result of both a higher case rate (8x higher) and a higher case mortality rate (70% higher).

This makes it pointless to keep comparing Europe and Asia on a daily basis. There is, obviously, something very, very different going on in Asia, and I doubt that better quarantine and masking rules can truly account for a 14x difference.

I've written about this before, and nothing much has changed since then. We still don't have a good explanation for what's going on.