Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through February 20. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Cats, charts, and politics

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through February 20. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

Yesterday I wrote about the apparent tendency of Texas power plants to literally catch on fire and explode if demand for electricity gets too high. My deeply considered response was basically "Huh?" Today, though, a reader emails to explain things to me.

The story starts with the fact that our electric system is based on 60 Hz AC. This means that the direction of the current reverses 60 times per second, and obviously the entire grid needs to be in sync:

The fundamental reason why grid operators have to resort to induced blackouts to protect their generation stations (and why it's sometimes done automatically) is that AC frequency management is everything in grid safety. Every generation hooked to the grid that uses physical motion (typically a turbine) has huge, expensive, precise turbines turning at some local multiple of 60Hz, and all of them are putting out AC whose waves are synchronized with one another. A small gas plant in El Paso phase peaks within a few milliseconds of when the steam turbines at the Comanche Peak nuclear plants do.

Under normal conditions that's just how AC power works — if it wasn't in sync no one would get power anywhere. Under strain, such as when demand surpasses capacity, frequency starts to drop — turbines start getting more magnetic resistance from their coils, solar inverters start heating up, wind turbines get more rotational resistance from their generators, etc. Most of that equipment can't tolerate going out of phase or frequency target more than slightly before it's damaged in big expensive ways. Hence they'll trip off the grid to protect themselves if needed, and grid operators have to drop loads rather than letting the frequency drop when they're out of generation capacity. They wouldn't "blow up" if they just stayed connected, but the damage would be real. There's nothing special about Texas' grid in that respect — all AC grids work that way.

There's a whole side market in energy just around frequency management — batteries and generators that can add or take away energy just to maintain stable frequency in the phase of short-term load shifts. It's fascinating stuff if you're into that sort of thing.

Another reader writes:

Remember the testing done around Y2K or thereabouts of whether you could actually damage a generator through the Internet? They destroyed a really big diesel generator with astonishing ease by oscillating the load to form a standing wave and ruined it beyond repair. Mind you, diesels are not known for being fragile, and certainly not as fragile as a turbine. These are big, macho machines, and each one is essentially a one-off custom build, so when one is severely damaged, it might take years to replace.

This YouTube explains in graphical terms:

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through February 19. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

A few days ago I wrote that our overall response to the COVID-19 pandemic had been pretty good, all things considered. I also mentioned that my post was basically a reply to Lawrence Wright, who argues that our pandemic response has been "one of the greatest failures in the history of American governance." He bases this on three big mistakes:

This struck me as laughably thin. Wright admits that #1 is the fault of the Chinese and there was nothing we could have done about it. #2 is real, but I doubt very much that it had much of a long-term effect. Europe had tests earlier than us and their outbreaks were just as bad.

As for #3, the CDC could have done better. But there really was new research being done in real time, and it was only slowly that mask wearing was tested as a way to prevent the spread of the virus. Previous research had been mostly about protecting the mask wearer, and the CDC was correct in saying that this was of limited use. European countries were in the same boat, and they changed their minds at about the same time we did.

All in all, this just isn't the devastating indictment Wright thinks it is. But the funny thing is that he missed the truly greatest mistake we made. Take a look at this chart of COVID-19 deaths:

This is a chart of all European countries plus the US. In the early days, the US is at the low end of the pack. Despite our missteps, we're not doing too badly. But during the summer of 2020 the pandemic dies down in Europe but keeps shooting up in the US. By November we're doing worse than all but four or five European countries.

Why? Because Donald Trump insisted on reopening the economy too soon. Unlike Europe, we never crushed the virus to near zero. Instead we kept on killing people all through summer, and when winter came we were starting from a higher base. I think it's safe to say that this one mistake probably cost a hundred thousand lives or so.

This is why I rate our overall response to the pandemic as "pretty good." We really didn't make as many deadly mistakes as people think, and overall the CDC and FDA did a fairly reasonable job. The one big mistake we did make came down to a single sociopathic man whose motivations, as always, were beyond human ken. Electing Trump president was our only real mistake, and we did that long before anyone had ever heard of COVID-19.

NUTSHELL VERSION: We mostly responded fairly well to the pandemic, especially given how new it was and how the science behind it was changing rapidly in real time. On the vaccination front, our response has been all but miraculous.

We made only one big mistake: allowing Donald Trump to be our president. My take is that this is not enough to condemn the entire US response. It's only one thing. On the other hand, it was a big thing and we did elect the man. If you think it's sophistry to say "it was only one thing" when the result was so catastrophic, I can't really blame you. I think it's important to understand just where we went wrong, but I'm less concerned with how you then describe it.

Whenever I go on a photo expedition I try to find at least one cat to take a picture of. This puts a little variety into Friday Catblogging.

No luck this time, I'm afraid. However, I did get some pictures of horses. None of them were showstoppers, so I picked this one because I liked the dramatic mane highlighted by the sun. Consider this the first and probably last Friday Horseblogging.

This year is the 25th anniversary of the great Welfare Reform act of 1996, which means we will all be treated to loads of thumbsuckers about whether "it worked." This is a conversation I'm eager to avoid, since the question of whether it worked is almost entirely a question of values.

But I was curious about one thing. The stated goal among Republicans was to push more single mothers into the workforce. So I wondered: by their own lights, is it fair to say it "worked"? Did it really push more single women to find jobs?

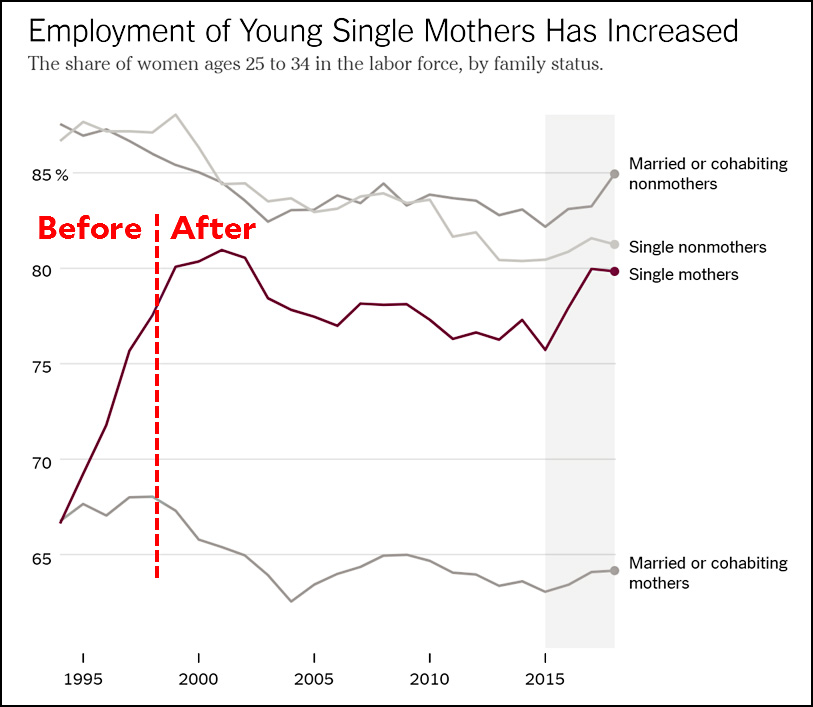

Here's a chart from the New York Times that shows what happened:

Welfare reform passed in 1996 and spent 1997 being implemented. So it's fair to say that 1998 is sort of the dividing line for "before welfare reform" and "after welfare reform." There are several odd things here.

First, as many people have pointed out, single mothers were piling into the workforce well before the welfare reform bill had a chance to have any impact. In fact, just a glance at the numbers makes it clear that welfare reform, at most, raised labor participation only slightly above where it was already at.

Second, the labor participation rate declined gradually over the next 15 years, and it declined at the same slow rate through both recessions and economic expansions. That seems weird. Then, in 2016, it suddenly shoots up for no apparent reason. What's up with that? Whatever it is, it hardly seems like welfare reform could be the culprit.

So did welfare reform "work" according the metric that conservatives themselves set out? It's hard to say. Something caused lots of single mothers to get jobs during the '90s—and to keep them through the first 20 years of the aughts (most of them, anyway). One possibility that's related to welfare reform is that in the early '90s lots of states were experimenting with tightening standards for welfare benefits, and talk of national welfare reform was in the air. Might that have something to do with it? I'd rate it fairly unlikely since the early efforts were weak and welfare recipients almost certainly had no idea that welfare reform was getting a lot of attention in Washington DC.

But if it wasn't welfare reform that did it, what was it? The burnout of the crack epidemic? A new generation of single mothers who were less lead poisoned than earlier generations? Some kind of weird statistical artifact? I don't know, but from the very beginning there's been something of a puzzle about why single mothers started entering the workforce in large numbers before welfare reform passed and before the economic boom of the late '90s started up. There are mysteries here that deserve a look.

There's been guffawing on both sides over the fact that Texas now has its own electricity crisis to match the one California had in 2019. This is because there are a surprising number of people who judge the success of conservatism and liberalism by which state is "doing better." It's a weird little game.

In this case, though, it turns out that both states suffered from the exact same problem: private companies that declined to bother themselves with taking safety seriously.

In the case of Texas, their power operators didn't engineer their systems to fail gracefully in the face of a huge weather event. That's expensive! This left them with only one option when that event finally occurred: they pulled the switch on millions of customers and left them completely without power for days. This was because they didn't want to spend the money to do things right, and Texas regulators let it slide.

California, on the surface, looks entirely different, but is actually nearly identical. The simple story is that the long series of blackouts in 2019 were caused by a manic wildfire season. But why should wildfires cause blackouts? Not because the fires damaged power plants or transmission lines. It was the other way around: faulty transmission lines can cause wildfires. And why can they do that? Because even after a decade of lawsuits, judicial orders, and attention from regulators, PG&E refused to fix its thousands of spark-prone power lines running through national forests. Everyone knew how to do it—better maintenance of transformers, clear cutting areas around transmission towers, etc.—but PG&E just didn't. So when the high winds came, they shrugged and turned off people's power instead. After all, they're already bankrupt thanks to other acts of negligence. They can hardly afford a spate of new lawsuits claiming that their transmission lines destroyed entire towns—as they had the previous year in Paradise.

It doesn't take a degree in engineering to figure out the solution to these twin crises: private utilities need to be regulated in a serious way. They won't spend money on avoiding seemingly rare events unless someone makes them, and that someone is the state legislators, the regulatory commissions, and judges. They've now failed in the two biggest states in the union. Who's next?

A Texas power official says they were "seconds and minutes" away from long-term catastrophe:

In an interview with the Texas Tribune, Bill Magness, the president of the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, said that if the utility did not cut power on Monday, the amount of energy going offline due to the storm, combined with a surge in demand amid the intense cold, could have caused widespread blackouts lasting for months, leaving the state in an “indeterminately long” crisis.

....In that disaster scenario, demand for power would have overwhelmed the supply of energy on the grid, which could potentially cause power stations to blow and equipment to catch fire. Once physical infrastructure takes such severe damage, it can take months to repair and would demand a slow process to return power sources back to the grid.

Wait. If demand for power is too high, power plants can blow up? Sort of like a bad Star Trek computer when you ask it a difficult question?

I know nothing about power generation, but seriously? You can make a power plant blow up simply by demanding too much electricity? I would sure like to hear an explanation for this. Is it common to all power plants and grids? Or just those in Texas?

ERCOT has a last resort option: ordering transmission companies to reduce demand on the system with rotating outages for customers....Usually, those outages are limited to less than 45 minutes. But this week, the outages lasted days. That’s likely because after ERCOT ordered companies to stop providing power to customers, even more power generation tripped offline, and it was not able to “roll” the outages effectively, Johnson explained.

So if the power deficit is too big, they can't even roll their rolling blackouts, as they usually do? They just have to choose some unlucky schmoes and cut their power for days?

It sure sounds like Texas power utilities are badly fucked up. They apparently have almost no ability to fail gracefully, something that every engineer in the world counts as a high priority. But I guess it would have been too expensive, and who expects bad weather in Texas, anyway?

Here’s the officially reported coronavirus death toll through February 18. The raw data from Johns Hopkins is here.

A new law has been proposed in Australia that would require social media companies to pay for the news items they promote. Facebook has responded by cutting off all news feeds in Australia, and the Australians are not happy:

Facebook’s brazen move could easily backfire. Facebook is facing new regulation and legal scrutiny globally, and the move is a clear demonstration of the harm that can be caused by a company wielding such enormous power over free expression.

....“Their decision to cut off news in Australia is a demonstration of their raw technical power and their willingness to use it for their own ends,” said Drew Margolin, professor of communication at Cornell University. “It reminds me of Mr. Burns’s decision to block out the sun in the Simpsons movie — it stokes fear but also encourages resistance.”

....Following Facebook’s move, hundreds of publishers lost access to revenue and readers previously gleaned from the site.

Hold on a second. I have two thoughts:

In a nutshell, one party (news publishers) wants to charge another party (Facebook) higher rates. This kind of thing happens all the time. It's practically the foundation of capitalism. If the buyer decides the price is too high, they don't buy. That's all Facebook did.

Second, aren't we all up in arms about Facebook's news feeds and how they're destroying democracy? Shouldn't we be delighted to see them cut off news altogether?

Wait. Three thoughts. Shouldn't Australian publishers be ecstatic to no longer be under the Facebook lash? Now they can promote their work without having to worry about Facebook's endless algorithm changes and paywall hacks. More generally, publishers need to make up their minds. Is Facebook good for their business because it sends lots of traffic their way? Or is it bad for business because it steals ad revenue from them?

Now, it's true that Facebook is doing this as a way of pressuring the Australian government to back off. They are undoubtedly afraid that if Australia passes its law and gets away with it, similar laws will spread across the rest of the world in short order. Still, what's wrong with that, beyond normal concerns about a big company lobbying for its interests?

There is something incoherent about our attitude toward Facebook. We don't just think of them as a big, powerful company, but as practically a demon lord run amok. If they run a news feed, they're single-handedly undermining civil society. If they cut their news feed, they're trying to destroy the news business. Meanwhile, the evidence that Facebook's curation of news actually changes much of anything in the real world is surprisingly thin.