For the past week or so Bob Somerby has been writing about whether doctors believe that Black patients are more tolerant of pain than white patients. In particular, he's been writing about a frequently cited study from 2015 which you can read here if you're so inclined.

Now, Bob is practically trolling me here. This kind of thing is right in my wheelhouse: read the study, explain the ins and outs, and discuss the results. But there's a problem: I've probably read this study half a dozen times over the past few years and I read it again last night. And I've never written about it because I've never been able to make sense of it.

This is weird because the study itself is the simplest possible kind: it's a survey of white medical students and residents—hereafter S&Rs. They were asked 15 questions about biological differences between Black people and white people, four of which were true and 11 of which were false. Here are the questions:

- On average, Blacks age more slowly than Whites.

- Black people’s nerve-endings are less sensitive than White people’s nerve-endings.

- Black people’s blood coagulates more quickly—because of that, Blacks have a lower rate of hemophilia than Whites.

- Whites, on average, have larger brains than Blacks.

- TRUE: Whites are less susceptible to heart disease like hypertension than Blacks.

- TRUE: Blacks are less likely to contract spinal cord diseases like multiple sclerosis.

- Whites have a better sense of hearing compared with Blacks.

- Black people’s skin has more collagen (i.e., it’s thicker) than White people’s skin.

- TRUE: Blacks, on average, have denser, stronger bones than Whites.

- Blacks have a more sensitive sense of smell than Whites; they can differentiate odors and detect faint smells better than Whites.

- Whites have more efficient respiratory systems than Blacks.

- Black couples are significantly more fertile than White couples.

- TRUE: Whites are less likely to have a stroke than Blacks.

- Blacks are better at detecting movement than Whites.

- Blacks have stronger immune systems than Whites and are less likely to contract colds.

The problem with the study is that after presenting the results of the survey it immediately dives into a long and messy bunch of weird measurements and unclear statistics. Its conclusion, based on the survey plus an additional set of questions, is that holding false beliefs doesn't much change assessment of pain in Black people and it doesn't substantially change recommendations of pain relief to Black and white patients.¹ The only noticeable effect is that S&Rs who hold a lot of false beliefs tend to have higher assessments of pain in white people.

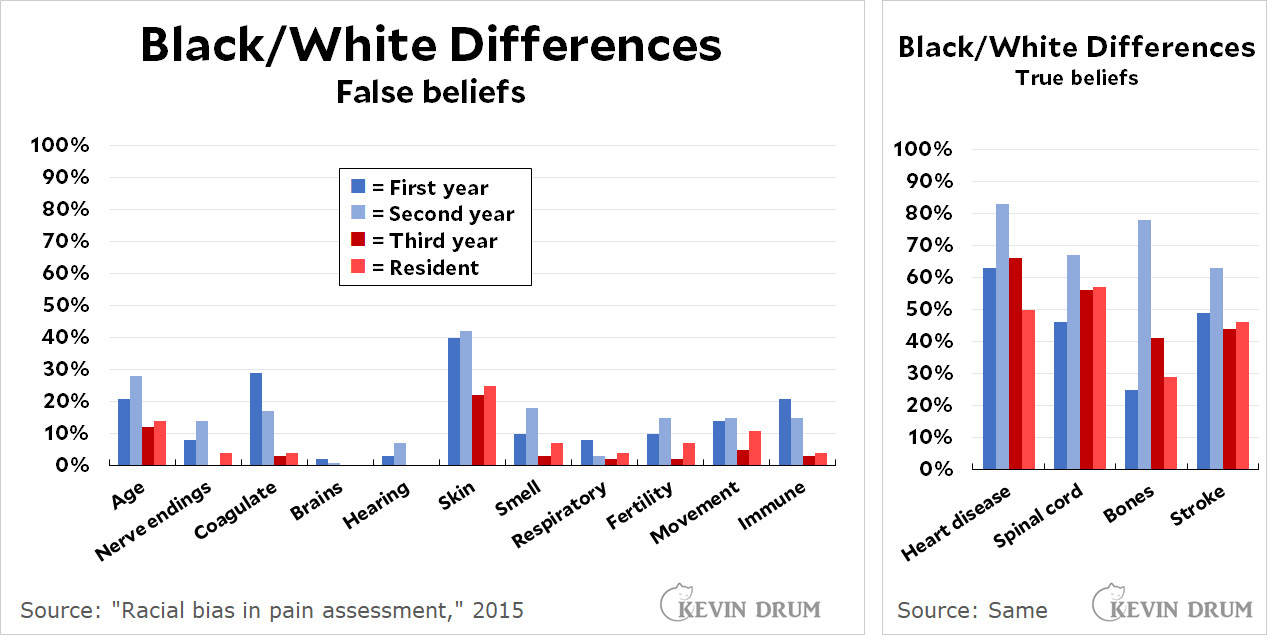

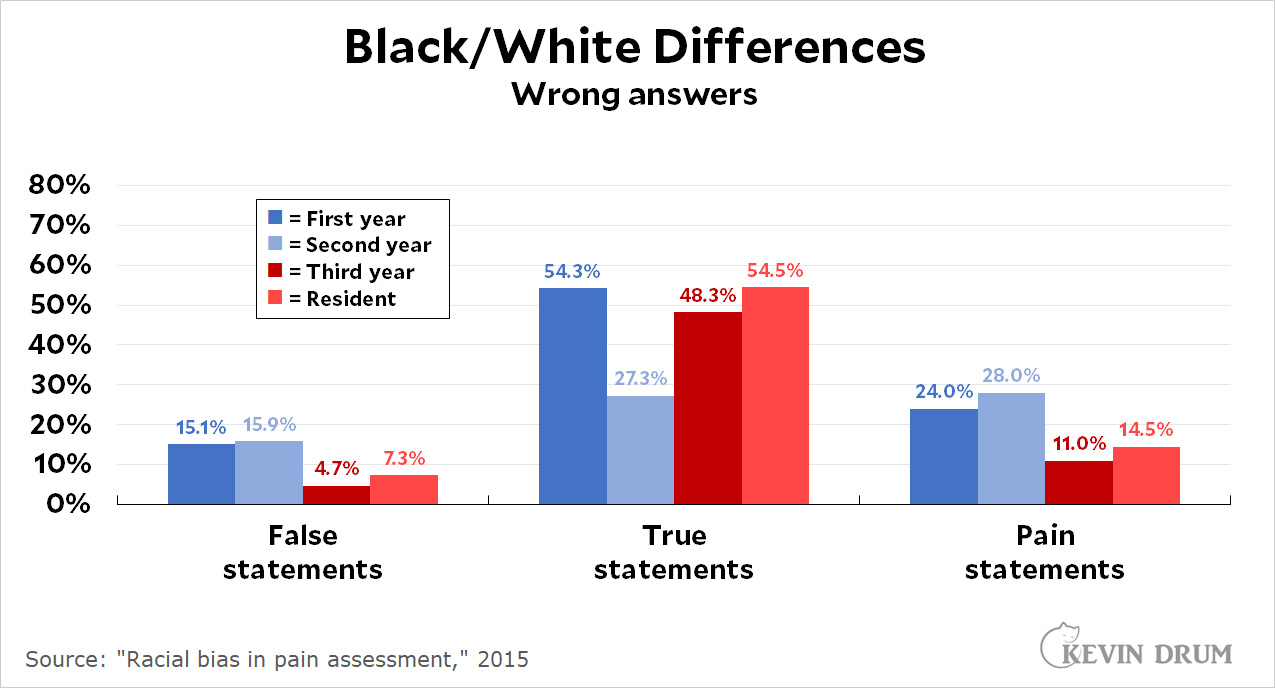

That's a pretty weak result, especially given the deficiencies in the survey design. But for our purposes, let's keep things simple and just take a closer look at the survey responses. First, here are the basic results:

There are a few things to notice here:

- Third years and residents generally do much better than first and second year med students on the false beliefs. Very few mark them as true.

- Second years are more likely to mark something true whether it's true or not. They marked 31% of the statements true, compared to 23% for first years and 17% for third years and residents.

- The respondents do worse on the true statements than on the false ones:

Roughly speaking, about 10% of the respondents mark false statements as true. However, about half of all respondents mark true statements as false. Second year students do much better on the true statements but not so great on the false statements (or the pain statements). - Answers are given on a scale of 1-6. S&Rs are allowed to mark an answer as "possibly," "probably," or "definitely" true or false. With one exception, which I'll get to, virtually every single person who marked a false statement as true said it was only "possibly true." Among all the false statements, there were 229 marks of "possibly true" and only 9 marks of "probably true." There was not a single mark of "definitely true."

I said there was one exception, and this is it: I didn't count the marks from the question about the thickness of Black skin. This is the huge outlier, with 41% of first and second-years believing it and even 23% of thirds and residents believing it.

So what can we conclude? Not much, but I'd toss out a couple of things:

- There does seem to be a problem with the belief that Black skin is thicker than white skin. This is worth addressing.²

- Beliefs of white and nonwhite respondents are virtually identical. In particular the average score for nerve endings is 1.94 vs. 1.83 (nonwhite S&Rs are more likely to believe it) and 1.76 vs. 1.73 for skin thickness. Overall, the belief in false statements is 2.06 vs. 1.98, meaning that nonwhite S&Rs are slightly more likely to believe them than white S&Rs.

- Belief in false statements is not a problem. The percentages are low and the responses are almost all tentative.

- However, S&Rs are apparently so afraid of saying they believe in any Black/white differences that they do very poorly on the statements that are true.

Overall, this is a dog's breakfast of a study. The authors end up focusing on whether S&Rs who harbor more false beliefs also tend to rate pain lower in Black patients compared to better-informed S&Rs. It turns out they don't, but they do rate pain in white patients higher. However, the amount is smallish; it makes little difference in treatment; and the statistics presented seem cherry-picked and gnawed at a little too carefully. I'm not really sure I put much stock in the authors' conclusions.

I'd recommend that no one cite this study—and if you do, at least cite it correctly. The authors don't make this easy, but if you want to play with the raw data go here and click on "Study 2" and then on "Data - Raw and Cleaned." Be sure to first read the main report carefully, though. For example, you'll want to remove all nonwhite respondents since the study was solely of attitudes from white students and residents. And you'll want to understand the response scale. Etc.

Overall, though, I'd say you shouldn't bother. It's just a simple survey with weak results. The real question is why no one seems to have done much research on this question since 2015. The treatment of Black patients is an issue of high interest these days and you'd think there would be more about it.

¹The measured difference is 15% of a standard deviation. That's pretty small, the equivalent of less than a half inch in height in the human population.

²However, it's worth noting that this is an active area of research that has produced some contradictory results. See here, here, here, and here. That said, most pain isn't affected by skin thickness anyway. If you fracture a bone or have a heart attack, there's no reason to think white people will suffer worse pain than Black people.

"The authors end up focusing on whether students who harbor more false beliefs also tend to rate pain lower in Black patients. It turns out they don't, but they do rate pain in white patients higher. "

I guess I don't get the difference. When you say "rate pain lower in black patients," my first question is compared to what? If it is lower than how they rate white patients, then it seems to me that rating pain lower in black patients and rating pain higher in white patients are the same thing.

I'm curious: for the four statements that are true, do we have have a handle on causation. For instance, if I were shown the statement about heart disease, I'd probably want clarification: are you asking if African ancestry correlates with innate (that is, genetic) propensity to suffer from heart disease? My guess would be the answer to that is "no" — it's due to socioeconomic factors, diet, etc.

Confusion about what the questions are really asking might have an effect on results.

How do questions about redheads and pain affect this?

I agree that it would be a good idea for Kevin Drum never to cite this study. He doesn't have any idea how to critique this study and he knows nothing about pain studies. He doesn't know the literature in this area, showing undertreatment for pain for various minority groups, including women and infants, not solely black people. Earlier studies showed undertreatment for people of various ethnicities, such as Eastern European immigrants.

This is not a valid criticism:

"The problem with the study is that after presenting the results of the survey it immediately dives into a long and messy bunch of weird measurements and unclear statistics. "

This only reveals that Drum, like Somerby, doesn't understand what the study is analyzing. Like Somerby, Drum largely ignores the treatment task and focuses on the false question ratings, which only serve the purpose of classifying those subjects with misinformation about black physiology. The relation of that misinformation to the pain treatment portion of the study is the whole point, yet Drum brushes those significant correlations aside.

This is what happens when non-specialists try to jump into a domain with insufficient knowledge to interpret what they are reading.

Like Somerby, Drum substitutes his own lack of knowledge for the judgment of PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Science) peer reviewers and pain researchers, dismisses a result he does not wish to acknowledge, and pretends that every study should be accessible to the general public without any background or training in medicine, pain research, measurement (creation of surveys) or experimental research. Neither Drum nor Somerby would be saying anything about this study if it did not touch on race, and the defensiveness of both men is obvious. In Drum's case, he works very hard to discredit a study that doesn't even show anything important, if you can believe his summary.

What serious researcher suggests that any study can be summarily dismisses by simply saying that no one should cite it? When a study is problematic or contradicts other findings (as this one does not) that makes it more important to address in one's literature review. You don't get to just ignore the findings you don't like.

I think this incompetent analysis by Drum and Somerby's more specious criticism both come from untrained non-researchers who don't know what they are talking about. These are the critiques that can be safely ignored.

Somerby has become a bore and his style of argument is tedious, but the starting point for his comments was an opinion piece in the WAPO:

NORRIS (12/9/20): We are not just tussling with historical wrongs. A recent study of White medical students found that half believed that Black patients had a higher tolerance for pain and were more likely to prescribe inadequate medical treatment as a result.

Is that an accurate statement about the study ?

Also, the fact that the questions leave no "I don't know" option seems like a meaningful design flaw, doesn't it ?

Oh, I'm keenly aware of the research in this area. And as I said, this study finds no effect of wrong beliefs on assessment of Black pain. Both well informed and badly informed students rate it the same. However, badly informed students *do* rate white pain higher than well informed students.

However, in neither case does this affect treatment by more than a smidgen. 15% of a standard deviation, to be exact. That's a very small amount.

The authors don't make this easy to figure out, but it's from their own slope analysis. The plain fact is that *this* study simply doesn't show that med students in general are badly informed and it doesn't show that being badly informed has much effect on pain management.

There are also other problems with this study, including the fact that a non-random selection of students taking a particular class (or, worse, residents self selecting whether they want to bother taking it) is just bad design. Anyone with any background in survey design would notice this instantly.

Other studies have shown different things, but none of them have shown very substantial results. We need more and better studies in this area.

If the mechanism for the significant effect which was found in this study were racial bias, then the details of the wording of the questions would be less important, since it isn't actual knowledge driving the effect. With false statements, the logic of the statement and the issues about ancestry and genetic liability to heart disease (mentioned above) would be irrelevant, given that there is no actual basis to the false statement.

When you give subjects neutral statements, ambiguous statements, irrelevant statements, wrong statements, so there is no knowledge-based way to answer them, the subjects can project their own biases onto the statements. That's why a "possibly false, possibly true" statement will attract an answer consistent with a person's racial bias, not their knowledge -- they don't seem to know for sure and thus are guessing. Questions where subjects are forced to guess in the absence of certainty are widely used in psychology to allow researchers to estimate guessing bias (a systematic tendency to select an answer based on something other than knowledge, such as a preference for a response worded with the word "true" as opposite to one worded with the word "false." See all of the work by Kahneman and Tversky about judgments under uncertainty, framing effects and bias (Kahneman won a Nobel prize for that work). See also signal detection theory. Lisa Feldman Barrett has suggested using a similar approach to measuring racial bias, both by people who use their biases as a substitute for knowledge in situations of uncertainty, and for people who are the targets of bias when trying to evaluate whether an outcome was due to prejudice or accidentally adverse (chance). Analyzing how many people got each question right or wrong is fairly meaningless when the measure being correlated with pain treatment (or used to form test groups) is a set of 15 questions. Responses to the individual questions are meaningless and so is your analysis of each of them. This kind of approach is used in a variety of types of study, but it isn't surprising that it would not be intuitive to you, since you are not a psychologist and neither is Somerby.

This is one reason why Somerby's complaint about the survey question responses is specious. It sounds plausible but isn't. The absence of concrete knowledge about black physiology permits projection of bias that may later drive the pain treatment responses in that second task. If there were only ignorance operating, there would be no significant effect, especially not one consistent with undertreatment for pain, which has been identified in many studies, including chart review studies in ER rooms where people with broken bones have been undermedicated, in dentist offices, and in cancer treatment.

Nitpicking the specific answers to certain questions does not address this issue.

But my larger concern is the lack of respect both you and Somerby show for the researchers and the results of these studies. You confidently believe that your knee-jerk reactions to these studies is better than the skills (capacity to understand and review the literature, methodological training, medical knowledge and specific pain knowledge, and statistical skills of these professional and well-trained researchers, especially following a peer review by additional well-trained people who work in this field, many for years. That looks like hubris to me.

I did pain research myself before I retired from my job as a full professor. You and Somerby have no background that would justify the harsh criticism you have made based on very little knowledge in this area. That doesn't stop you from trashing the study. Somerby has been showing racial bias in his essays lately. His motive is to attack Norris and claim that the left is excessively woke. I haven't seen the same from you, but you might slow down your rush to support his hit pieces on studies (and journalists) addressing racism. Somerby misquoted Norris, who herself grabbed the results summary from the study itself. He has been doing this lately, manufacturing complaints that are not legitimately the fault of the journalists he attacks.

He never reads his comments (or he doesn't admit to it) and he never addresses or corrects anything based on comments. He frequently makes errors, including some huge ones involving statistics. He isn't the guy he used to be -- and I've been reading him since the beginning. I would advise greater caution when following him over one of his cliffs.

For the sake of the historical record, I'll offer a reaction to this part of what the commenter has said:

"Somerby has been showing racial bias in his essays lately. His motive is to attack Norris and claim that the left is excessively woke...Somerby misquoted Norris, who herself grabbed the results summary from the study itself. He has been doing this lately, manufacturing complaints that are not legitimately the fault of the journalists he attacks."

I have no desire to "attack" Norris. It's extremely depressing and draining to criticize people from one's own tribe, in large part because any such criticism produces ad hominem rebuttals of precisely this kind. Motives will be divined!

It's much easier and more rewarding to repeat the Established Mandated Truths of the tribe. To see this done on an endless loop, just watch cable news or read the columns of our standard columnists.

As for the idea that I've been "misquoting" Norris, I've been printing the exact text of something she actually wrote. I've interpreted the meaning of what she (somewhat fuzzily) wrote in the way which seemed to make sense.

Perry says that Norris merely "grabbed the results summary from the study itself." I'm not sure what that means, but for the record, she didn't link to the actual study. As I've noted, she linked to an essay by Professor Sabin, an essay including an ambiguous statement which Norris may have misread.

Two years ago, when I read what Norris had written, it struck me as a statement which may well be inaccurate. I've seen nothing in the study, then or now, which supports anything like what Norris wrote.

As I've noted, the authors of the study state their findings in a grossly misleading way right in their Abstract. The spinning of their meager findings can be said to get its start there.

Perry seems to say that Norris didn't get anything wrong and that it isn't her fault! Humor aside, I haven't spoken about "fault," though if Norris misstated what the study shows, that is plainly her doing, and it's the doing of her editor.

People do make mistakes. At any rate, I don't know of any way to read the study in which the statement by Norris which I've been quoting can be seen as even dimly accurate.

I also haven't used the word "woke" in any of my commentaries. Have I been "showing racial bias?" This is precisely the type of reaction on the part of our badly failing tribe which I have often criticized.

By the law of our badly failing tribe, if you challenge anything said by our tribe about "race," this kind of divination will instantly follow. Our tribe has become highly expert at the calling of names, while becoming increasingly inexpert at everything else.

Nothing in the UVa study supports the claims a range of journalists have put in print about it, or about the (white) medical students, who were crazily accused of holding disturbing 19th-century beliefs by the professor Norris cites as her source. According to Drum, nonwhite participants in the study recorded the same number of alleged mistakes. This fact is buried deep in the basement of the study, never to be mentioned again.

I regard the study's methods as very strange in a wide array of ways. Were I to leap to pleasing name-calling in the manner of the commenter, I would call him a "running dog" and leave the matter at that.

Perry skips past almost everything Drum has said about the study and its results. He accuses me of racial bias.

Drum says the study is a nothingburger, and he gives reasons for his claim; I'm prepared to assume that he's right, especially in the absence of rebuttal from the commenter. I've focused on what journalists have said about the study. It seems to me that their statements have routinely been grossly inaccurate, in a way which captures the route our tribe insists on taking on the road to our endless defeats.

Very few of those (white) medical students "endorsed" any false beliefs. That said, our tribe has developed a love for accusing people of racism.

We love love love love love love love to make that claim about Others. The claim is frequently stupid and ugly and unfounded or wrong, and it's also routinely self-defeating.

It makes us feel very good and very moral inside. Given our vast indifference to matters of race down through the many long years, we should possibly make an effort to step feeling that way.

Thanks for the explanation about forcing respondents to guess as a method to uncover bias. I read one of Kahneman's books a few years ago but I don't remember (or just missed) this point.