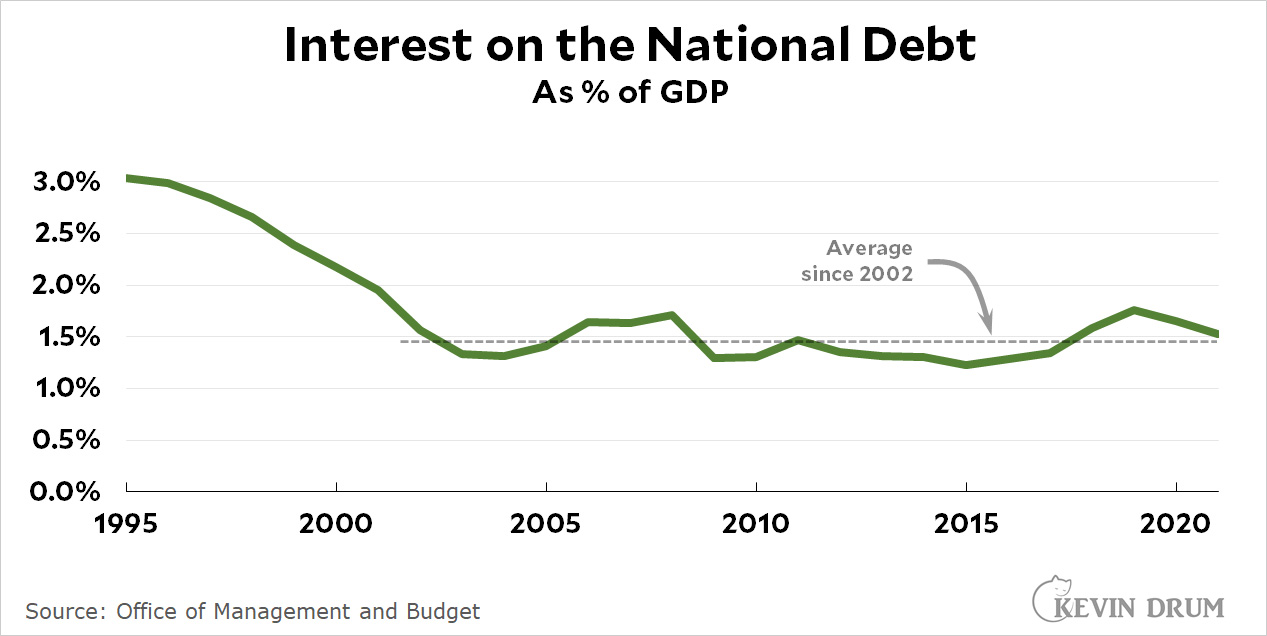

The national debt topped $30 trillion this week, "an ominous fiscal milestone that underscores the fragile nature of the country’s long-term economic health," according to the New York Times. However, a more important measure is the amount of interest we pay on that debt:

Interest on the national debt soared under Ronald Reagan and then returned to normal under Bill Clinton. For the past two decades it's been pretty flat at just under 1.5% of GDP. In 2021 it clocked in at 1.53%.

Interest on the national debt soared under Ronald Reagan and then returned to normal under Bill Clinton. For the past two decades it's been pretty flat at just under 1.5% of GDP. In 2021 it clocked in at 1.53%.

Of course, interest payments could increase if interest rates go up significantly. That doesn't seem likely right now, but the Fed has certainly signaled a modest increase in interest rates later this year. Combined with increased spending, this could add up to higher interest payments in 2022.

"Combined with increased spending, this could add up to higher interest payments in 2022."

And as a nation with a sovereign currency that is also the world's reserve currency, that's a problem . . . why?

It's not a huge problem given the modest levels, certainly, but close to 40% of the interest paid is received by foreigners, so, we're basically giving them claims on our production of goods and services. Also, the overall structure of the debt (namely, that it is skewed toward holdings by the affluent) represents an increase in the regressivity of the country's tax/transfer system writ large. Finally, the return of inflation suggests that monetization of debt is off the table, so the increase in interest expense will eventually have to be met by increasing taxes or cutting spending, either of which crimps living standards (save for those who are receiving the interest as income, mostly the rich).

"Finally, the return of inflation suggests that monetization of debt is off the table" Inflation is the definition of monetizing the debt. And it should be noted that 8.9 trillion of that debt is owed to the federal reserve, i.e. it never needs to be paid back and costs no interest.

Solution?

Cut taxes for the highest earners.

That is all.

It's just common sense.

Remember when Clinton blew up about Wall street bankers?

Take a look at this graph of interest as percent of GDP--we're about half of what it was in the late 80's/early 90's. Eyeballing, a return to that level would cost the Treasury $400-500 billion a year, or $4 trillion over 10 years, bigger than BBB.

Higher interests rates would certainly put pressure on the federal budget, but it would also mean investors in US treasuries could actually earn a return for a change. That's helpful, too.

And why should the Government hand money to people who happen to hold Treasury bonds? If the Government wants to hand out money, and it often does, surely there's more rational based than having the wherewithal to buy bonds?

The effect would be gradual, no? I thought the ten-year was the most popular Treasury, so the higher rate would only factor in at the rollover. Also, aren’t the Treasuries zero-coupon? So all the notes already sold are unaffected, until they mature and new bonds are issued. Is that how it works?

I came here to point this out. I don't know this for sure, but if the fed were to increase the interest rate I don't think current debt would be affected.

You're right. IIRC the Volcker interest rate squeeze was highest around 1981, but the impact on interest payments didn't peak until 1990 or so. Fed debt is a mix of short, medium and long term (30 yr) obligations with new bonds/notes being auctioned every month at so it takes years for the full impact to be felt.

Thanks, that's how I thought it worked.

Interest payments are all that ever matter. The balance sheet value of outstanding debt by itself is somewhat meaningless for extremely large organizations, completely meaningless for large countries.

The scare stories about rising interest rates and outstanding debt always seem to forget what happens to the market value of existing debt when interest rates spike. Might be ignorance, might be willfull deception....

Interest payments not paid to the general revenue fund of the US government are what count. the Fed owns 8.9 trillion of that 30 trillion debt. We simply pay ourselves that interest.

Interest on bonds held by the Fed is simply remitted back to the Treasury. Interest on bonds held by the private sector (us, mostly) is paid to us.

It's almost as if the NYtimes does not understand the importance of expressing this data in terms of a rate.....or 30 Trillion gets more clicks....this is why I canceled my subscription. The paper of record is a joke.

If we are going to raise interest rates by 1.5% over the next 18 months then the interest is going to go up significantly.

If the average life is about 7 years then 2/7 of the debt will increase by more than 1% over the next 18 months. Then that will be somewhere between 0..3% and 0.6% of GDP.

I can estimate Fed Funds rates for free but I can't do forward rates for longer term issues without a Bloomberg.

https://www.cmegroup.com/trading/interest-rates/countdown-to-fomc.html

This actually shows 7 increases are likely by July 2023.

So the interest payment would increase because current debt is continuously turning over? As in, at any given point in time there will be bonds maturing at the old rates and bonds being issued at the new rate?

Well, since the debt is increasing over time, it's likely something less than 2/7. But this fraction would also change if the mix of short vs long bonds varies from time to time. Also, how much of the Covid relief appropriations have actually been spent to date?

Biden just announced almost all.

You need to reduce the cost by the 30% of the bonds owned by the fed.

Then the chart should go back to before the Reagan administration…

Interest rates are completely and entirely at the will of the Government, which can and should keep them at zero forever, by the simple mechanism of having the Fed offer to buy in unlimited quantities at face value. There is no outside force that can stop the US Government from doing that if it wants to. Paying interest on Government bonds is simply giving money away on the basis of bond holding. I don't object to the Government giving money away, but there are better bases for doing it than that.