Question #1: Do you know what the following acronyms stand for?

- MRA

- FDA

- EMA

- GMP

For the record, they are: Mutual Recognition Agreement, Food & Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and Good Manufacturing Practices.

Question #2: If you didn't recognize all four of these acronyms, did you nonetheless have a strong opinion about whether the United States should automatically accept European approvals of European pharmaceutical facilities instead of always requiring its own?

Hmmm. Readers of this blog will probably not be surprised to learn that just because they haven't heard of something, that doesn't mean nobody is doing something about it. Various agencies, because they are not staffed with idiots, have been aware of this issue for more than two decades and have been working on it the entire time. And guess what? We do have a reciprocity agreement regarding pharmaceutical facility inspections with the EU (and Britain). Here's the history:

1998: First attempt at an agreement.

2001: Attempt fails. Everyone gives up for a while.

2012: Congress passes a law allowing the FDA to try again.

2014: Negotiations begin, mainly between the FDA and the EMA, but also with every national regulatory authority in the EU.

2017: An MRA is agreed to. The plan is to implement it for most ordinary facilities by July 2019; for veterinary facilities (which are under the authority of the USDA) at a later date; and for facilities that manufacture vaccines and plasma-derived pharmaceuticals by July 2022.

2019: The MRA is implemented as planned after the FDA reaches agreement with Slovakia, the last of the EU countries to gain US approval. By the end of 2020, agreement is reached in principle for veterinary facilities but is not implemented.

2020: The COVID-19 pandemic puts negotiations on hold. Both the FDA and the EMA are putting every spare resource to work on COVID.

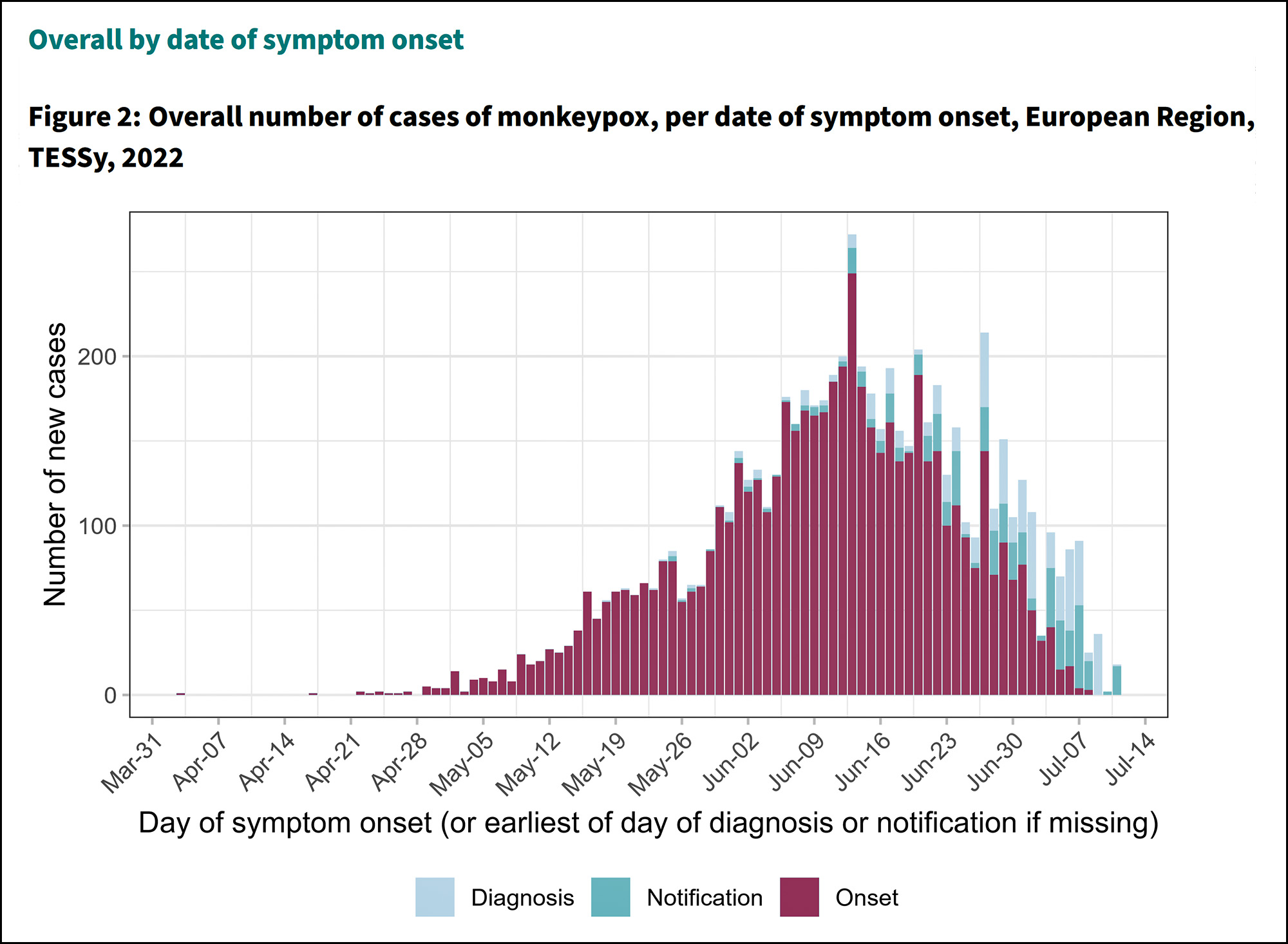

July 2022: Because of the pandemic delay, there is still no MRA today for either veterinary facilities or vaccine factories. Without this, it is not legal for the FDA to accept the results of an EMA inspection for something like the monkeypox vaccine. It must verify GMP itself.

This is the basic timeline and it doesn't seem unreasonable to me. In 2017 there was no special reason to hold up the main MRA for vaccines, so they didn't. Then, when COVID hit, the vaccine MRA was put on the back burner in order to expedite cooperation on COVID. That's also reasonable. The downside of all this is that when the monkeypox outbreak hit us earlier this year, there was no MRA in place for vaccine facilities.

The cost-benefit on these decisions is sky high. On the benefit side we have an MRA in place for nearly all human medicines. On the cost side we have a short delay in approval for a single vaccine aimed at a disease that's extremely mild. Monkeypox needs to be dealt with, but it's simply not a high priority compared to a killer like COVID.

Would any of you have done things differently given the resources available to you?

POSTSCRIPT: Whenever there's a panic over something like this, it spawns a widespread sentiment that (a) Agency X is moving too slowly, (b) they obviously aren't taking this seriously, (c) this is an emergency and they should ignore the rules, and (d) WHAT THE HELL IS GOING ON WITH THESE STUPID BUREAUCRATS AND THEIR STUPID RULES???

My advice: STFU unless you really, genuinely know what you're talking about.¹ The rules might or might not make sense, but they aren't stupid. And if we routinely cave in to Twitter mobs and discard them whenever public pressure gets heavy, someday we will pay a big price. And I wonder who will get the blame?

¹This does not include generic knowledge about the deficiencies and regulatory capture of Agency X. I'm talking about the nuts and bolts here.