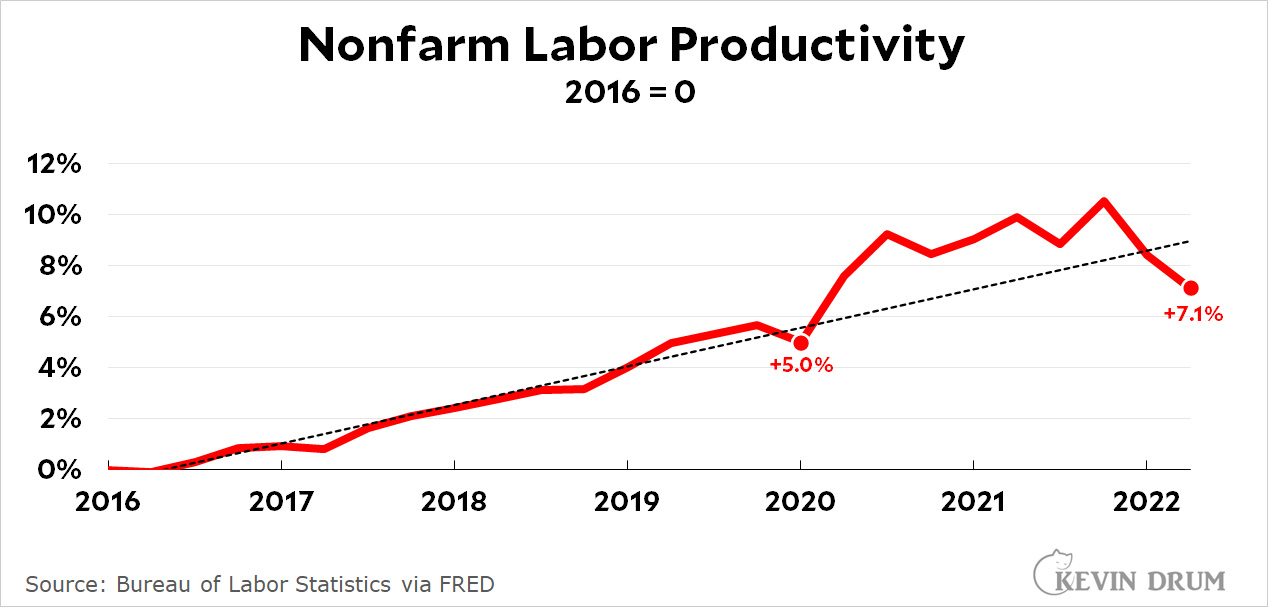

The BLS released productivity numbers for Q2 this morning, and the headline number is bad: a 4.6% decline from the previous quarter (at an annualized rate). This is bad, but in a slightly different way than it seems. Here's a chart that shows the absolute level of productivity, not the change from quarter to quarter:

This is, as usual, my favorite format. First I draw productivity from 2016 through the first quarter of 2020, just before the pandemic. Then I draw a trendline. Then I fill in the numbers from 2020 to the present.

This is, as usual, my favorite format. First I draw productivity from 2016 through the first quarter of 2020, just before the pandemic. Then I draw a trendline. Then I fill in the numbers from 2020 to the present.

What you see is that productivity went up faster than trend during the pandemic. This is because a huge number of people were laid off. Total output went down, but the number of workers went down even more. By simple arithmetic, this means that output on a per-person basis was higher than before.

As the pandemic eased, the opposite happened. Output went up, but the number of workers went up even more. The same arithmetic tells us that this means output on a per-person better declined.

There's nothing especially wrong with that. We should expect productivity to return to trend level once the economy has recovered. The problem is that this happened in the first quarter. But then, instead of leveling out, productivity declined again, taking us well below the pre-pandemic trend.

It's typical of recent recessions that productivity continues to go up or, at worst, stays flat. Usually, however, productivity keeps going up after the recession is over. This happened again this time, but only for a couple of years before it began to turn down. This is only the second time in 30 years that productivity has decreased two quarters in a row (the other time was in late 2012).

This is yet another indication of how strange the economy is right now: GDP is declining even as employment keeps going up. This is not usually how a recession works. (Nor is it how an expansion works.) So everyone is puzzled.

Here's one explanation that will probably ruffle some feathers: unemployment is too low. Employers have been snapping up anyone with a pulse, and this means they're pulling relatively unproductive workers off the sidelines. Many of them are now now stuck: hiring more people doesn't really improve output because the new workers are of such poor quality. They require more management time and more cleanup time after mistakes than they're worth. Maybe the conventional wisdom was right all along: 4% unemployment really is about the lowest it should ever get in an advanced economy like ours.

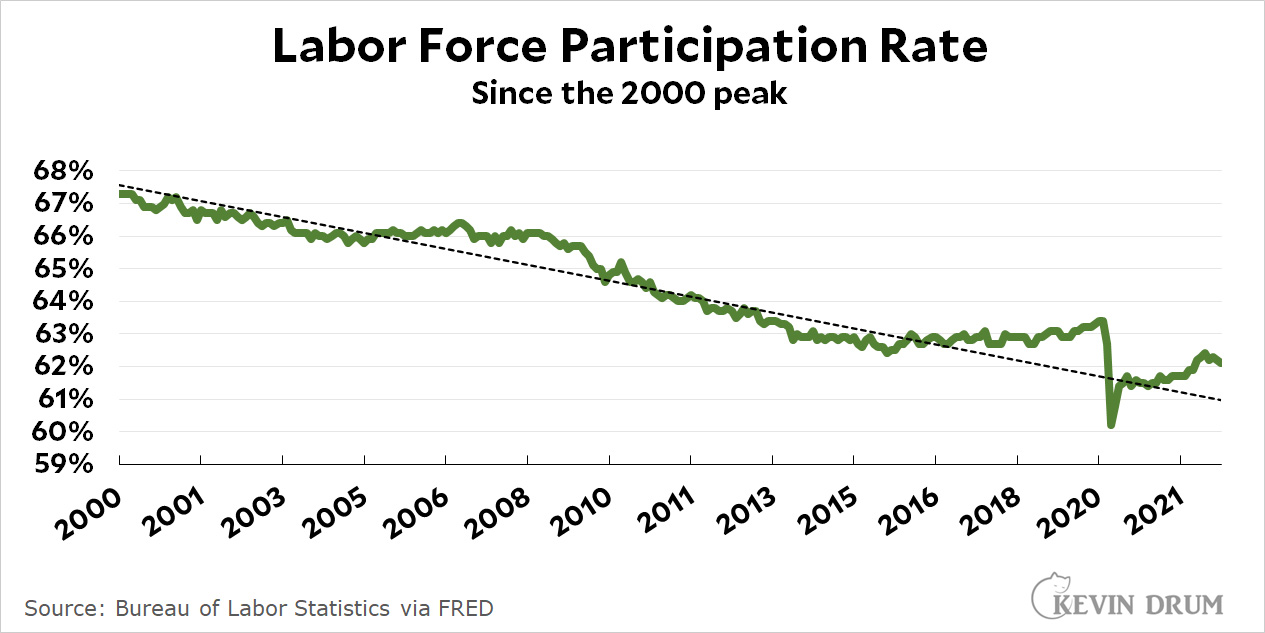

The way to return to growing productivity, as usual for the past century, is more machines. But things have changed. When the Industrial Revolution started, the productivity increase from automation was so great that we needed as many workers as before just to handle the huge increase in output. Lately, though, that hasn't been true. Automation has produced modest increases in productivity and the number of workers needed to handle the higher output has gone down. You can see that in the fact that the labor force participation rate has declined from its peak of 67% in 2000 to about 62% today. Here's what that looks like in a slightly modified version of my favorite format:

This time I drew the trendline through 2016, which shows a steady decrease in labor force participation. But then the participation rate flattened and even moved up in 2019. There was a huge downward spike during the pandemic, but the recovery put us right back on trend. Starting in 2021, however, participation grew well above trend.

This time I drew the trendline through 2016, which shows a steady decrease in labor force participation. But then the participation rate flattened and even moved up in 2019. There was a huge downward spike during the pandemic, but the recovery put us right back on trend. Starting in 2021, however, participation grew well above trend.

Perhaps it grew too much. Perhaps employers have been more reluctant this time around to replace workers with automation. But that's not likely to last. For the first time in quite a while I saw a movie on Sunday and there were no ticket sellers at all. The entire process at our local gigantic multiplex was handled by touch screens. Fast food restaurants are moving in the same direction. The eventual result is going to be fewer workers but a return to normal productivity growth.

This is our long-term future and we can't avoid it except for short periods here and there. We're apparently in one of those periods now, but we'll probably return to trend before long. That means some pain in the employment rate, which the Fed seems determined to make even worse, but eventually a return to normal labor participation and productivity rates.