Over at New York today, Zak Cheney-Rice has a long piece about the imminent death of affirmative action if the Supreme Court, as expected, kills its final foothold in higher education later this year. It's a good piece, with loads of historical detail, and Cheney-Rice is certainly correct that the backlash against affirmative action in the '70s was all but instantaneous:

[Affirmative action for jobs] was ultimately doomed by several overlapping factors: the GOP’s wholesale turn against Black communities, the white working class’s betrayal of their Black peers, and the government’s terror of sparking a backlash from white voters. Alongside the Harvard Plan [for higher education], it represented the other half of the affirmative-action equation: the idea that the government could help build a Black middle class the same way the labor movement made a white middle class, by creating good-paying jobs for low-skilled workers without a lot of education. And it never had a chance.

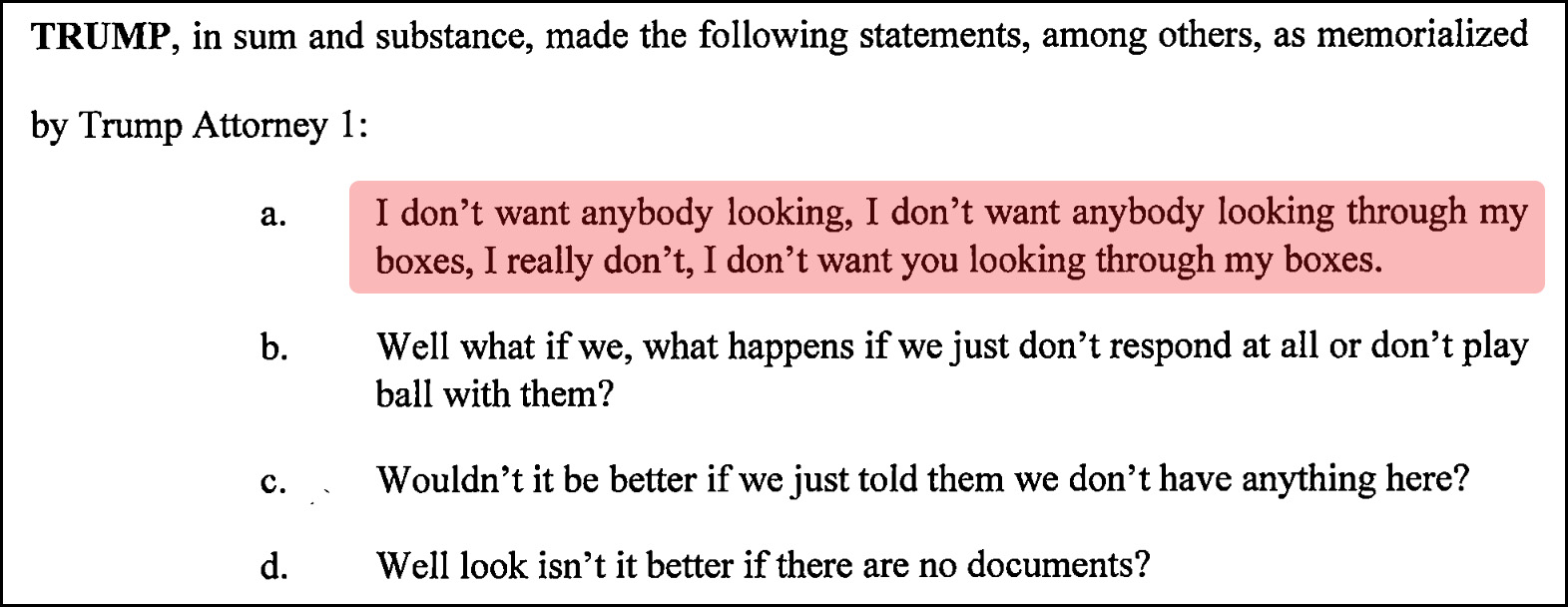

I hate to pick nits in a thesis that I think is basically correct. But there really is more to this story. For one thing, although it's true that whites have long opposed affirmative action, it's been unpopular even among Blacks for the past quarter century:

There are legitimate issues with affirmative action, and not all of them are motivated by white racial animus. These problems are serious enough that I've long believed class-based affirmative action would, on net, be a better policy than race-based affirmative action.¹

There are legitimate issues with affirmative action, and not all of them are motivated by white racial animus. These problems are serious enough that I've long believed class-based affirmative action would, on net, be a better policy than race-based affirmative action.¹

Black small business owners account for 6.7% of federal procurement spending compared to an overall Black business ownership rate of 8.9%. I don't know precisely what this number was in 1970, but I think it's safe to say that it was more or less 0%—and the increase since then has been at least partly due to minority hiring requirements.² That is, affirmative action.

Black small business owners account for 6.7% of federal procurement spending compared to an overall Black business ownership rate of 8.9%. I don't know precisely what this number was in 1970, but I think it's safe to say that it was more or less 0%—and the increase since then has been at least partly due to minority hiring requirements.² That is, affirmative action.

It's been one of my longtime wishes that we could all keep two thoughts in our heads at once. It is simultaneously true that affirmative action faced enormous opposition among whites from the very beginning and that it nevertheless had (and has) a continuing impact on Black outcomes in various areas.

In other words, things can be better but still need to improve. The evidence suggests that affirmative action has been effective for the past 50 years but that most people—including minority populations—don't believe it should last forever. Its importance has faded over time, but perhaps that's as it should be.

¹If you want more detail about why I believe this, I've written about it before. Here's a piece from 2003, here's one from 2010, and here's yet another from 2013.

²I would love to see a time series of this and related statistics, but I was unable to find one