David Brooks has a question:

Why have Americans become so mean? I was recently talking with a restaurant owner who said that he has to eject a customer from his restaurant for rude or cruel behavior once a week—something that never used to happen. A head nurse at a hospital told me that many on her staff are leaving the profession because patients have become so abusive.

At the far extreme of meanness, hate crimes rose in 2020 to their highest level in 12 years. Murder rates have been surging, at least until recently. Same with gun sales. Social trust is plummeting. In 2000, two-thirds of American households gave to charity; in 2018, fewer than half did. The words that define our age reek of menace: conspiracy, polarization, mass shootings, trauma, safe spaces.

The article is paywalled, so I can't read the rest of it. But you folks all know me pretty well, so you can probably guess what's next: Is it, in fact, true that we've become meaner over the last decade or so?

This is not an easy question to answer. We're interested in "mean" interpersonal interactions, not necessarily riots or murder rates. But who measures that? Who even decides what it is?

I thought about this for a short while and came up with some examples. Like Brooks, let's start at the extreme end:

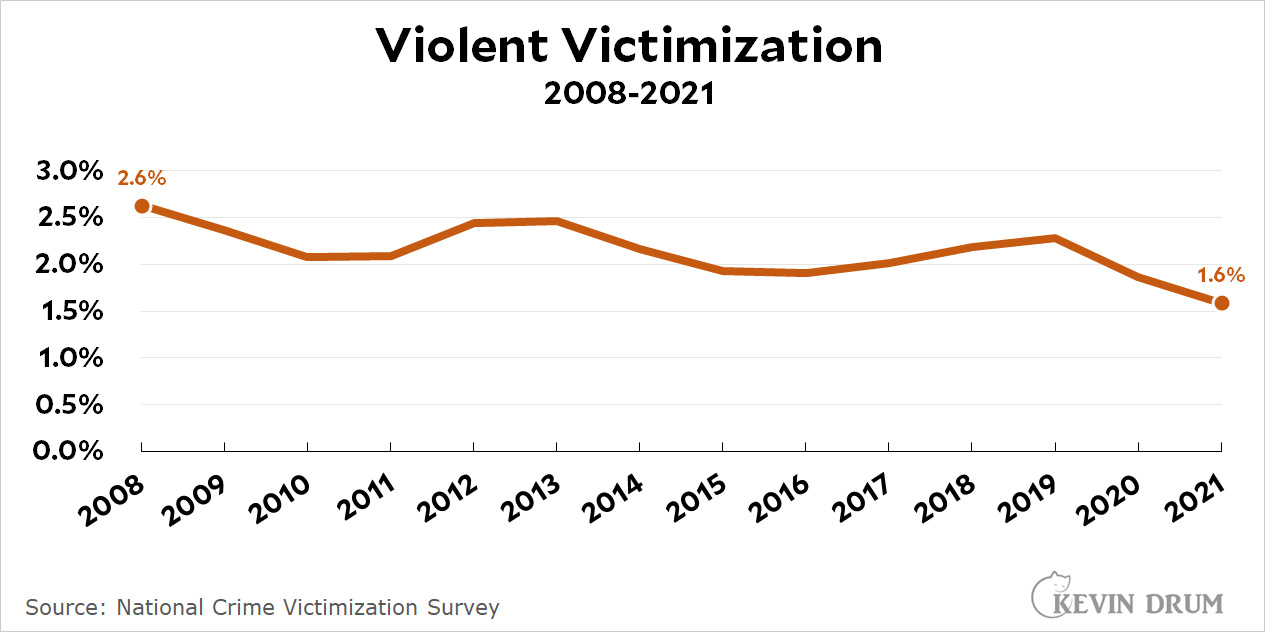

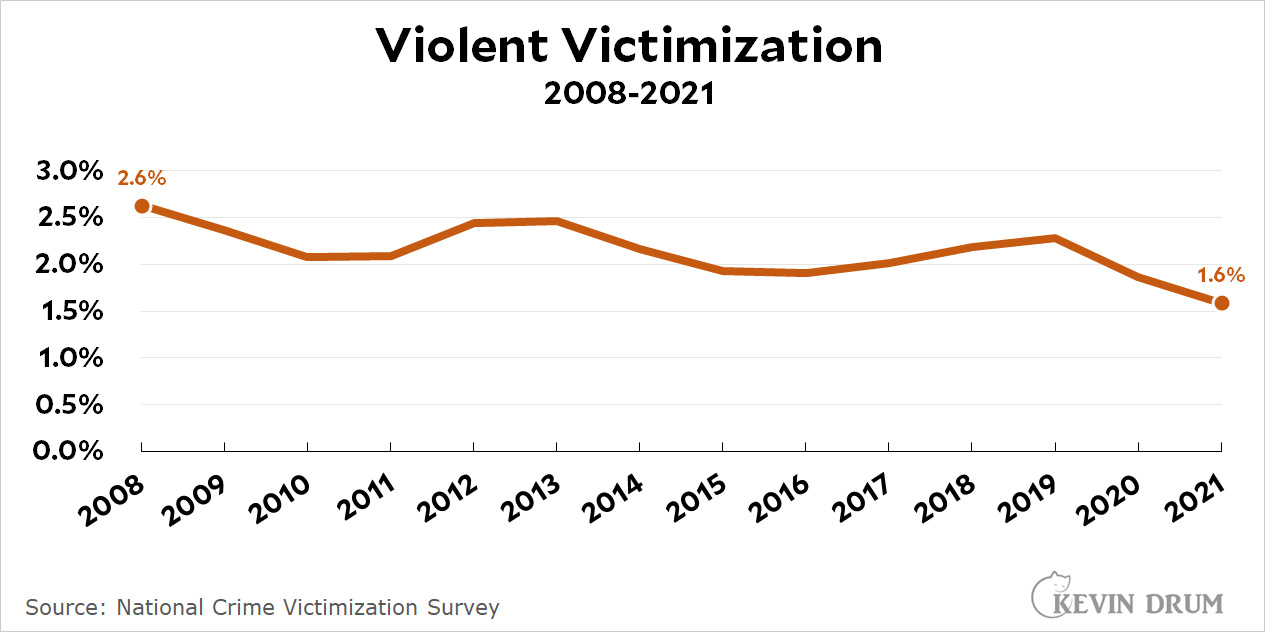

Violent victimization has been dropping fairly steadily over the past 10+ years. In 2021 it was a third lower than in 2008.

Violent victimization has been dropping fairly steadily over the past 10+ years. In 2021 it was a third lower than in 2008.

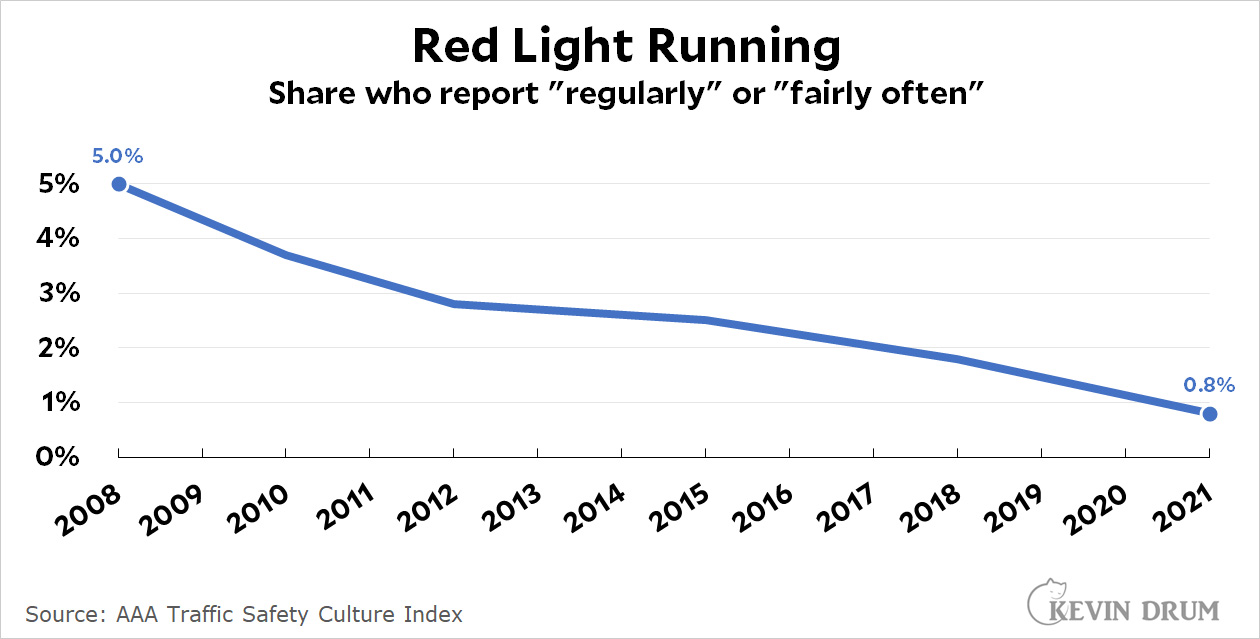

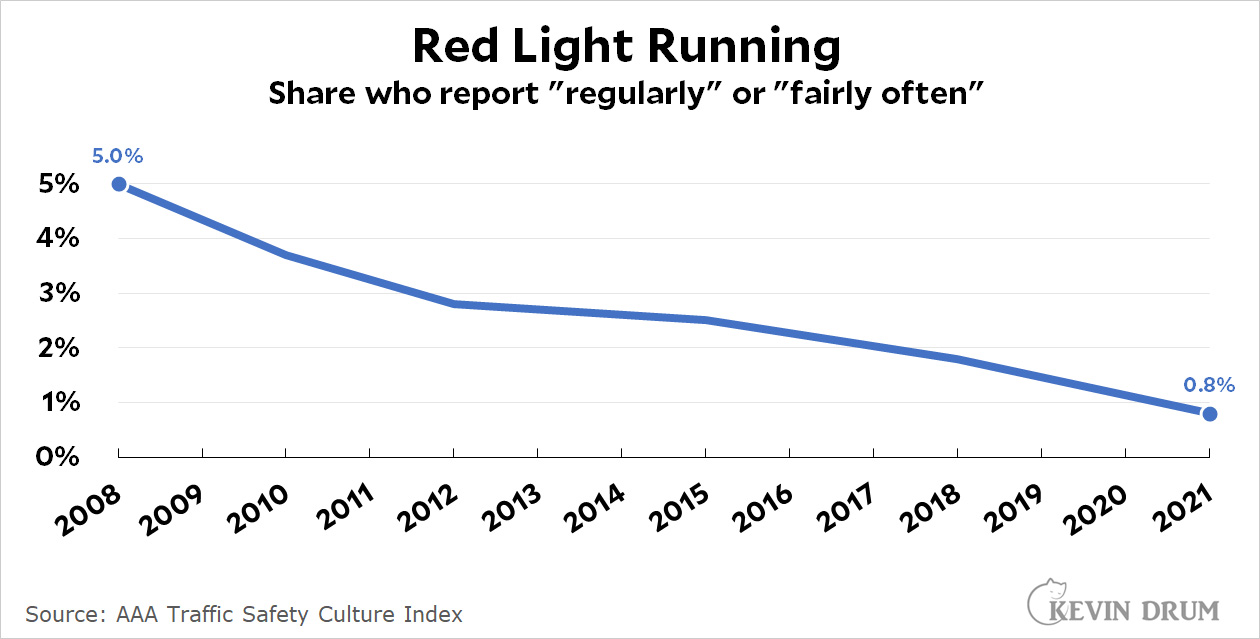

Stepping down the scale a bit, here is red light running, which is the best proxy for aggressive driving I could find in the AAA's annual Traffic Safety Culture Index:

Like every other measure of aggressive driving in the AAA report, it's down substantially since 2008.

Like every other measure of aggressive driving in the AAA report, it's down substantially since 2008.

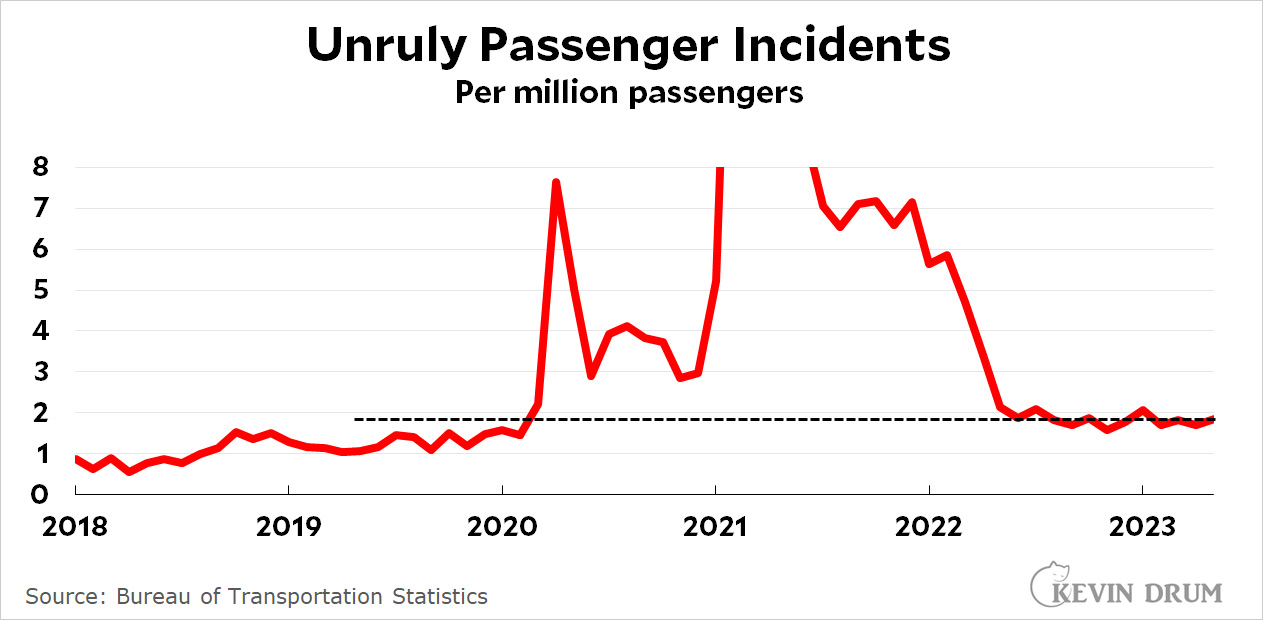

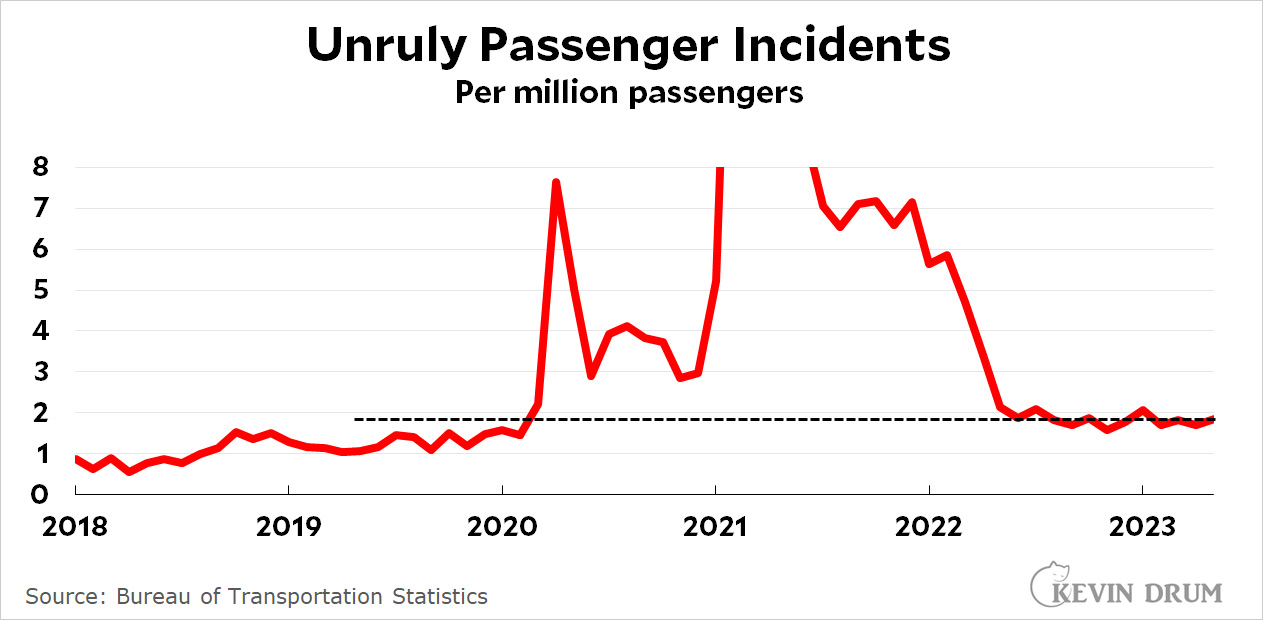

Here are incidents of unruly airline behavior reported to the FAA:

This has been going up—but not by a whole lot. The latest figures are only slightly higher than just before the pandemic, and are heading down.

This has been going up—but not by a whole lot. The latest figures are only slightly higher than just before the pandemic, and are heading down.

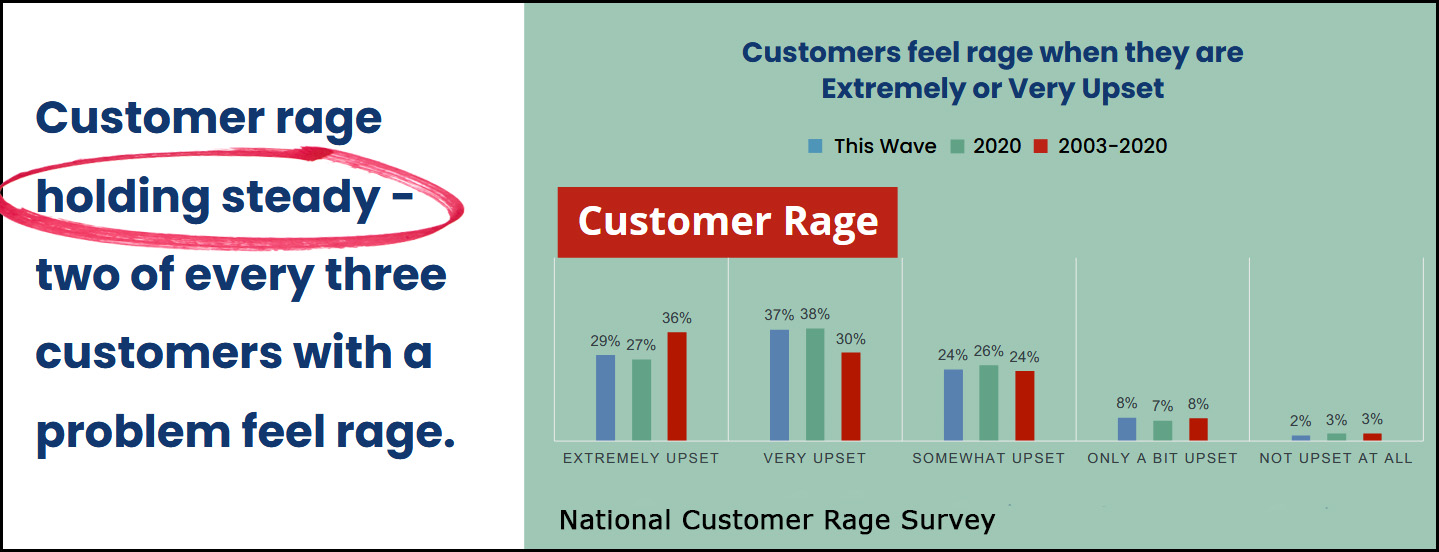

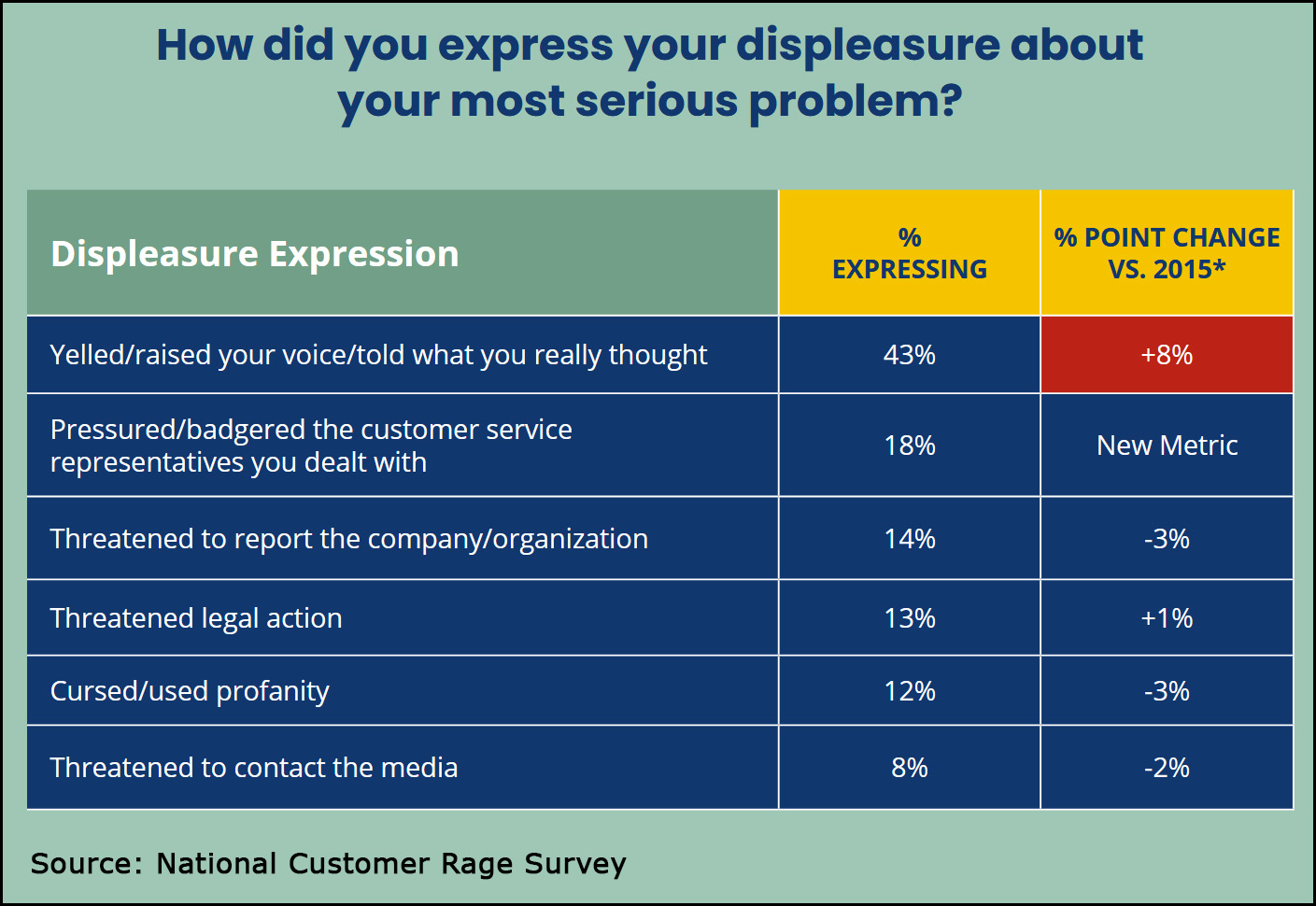

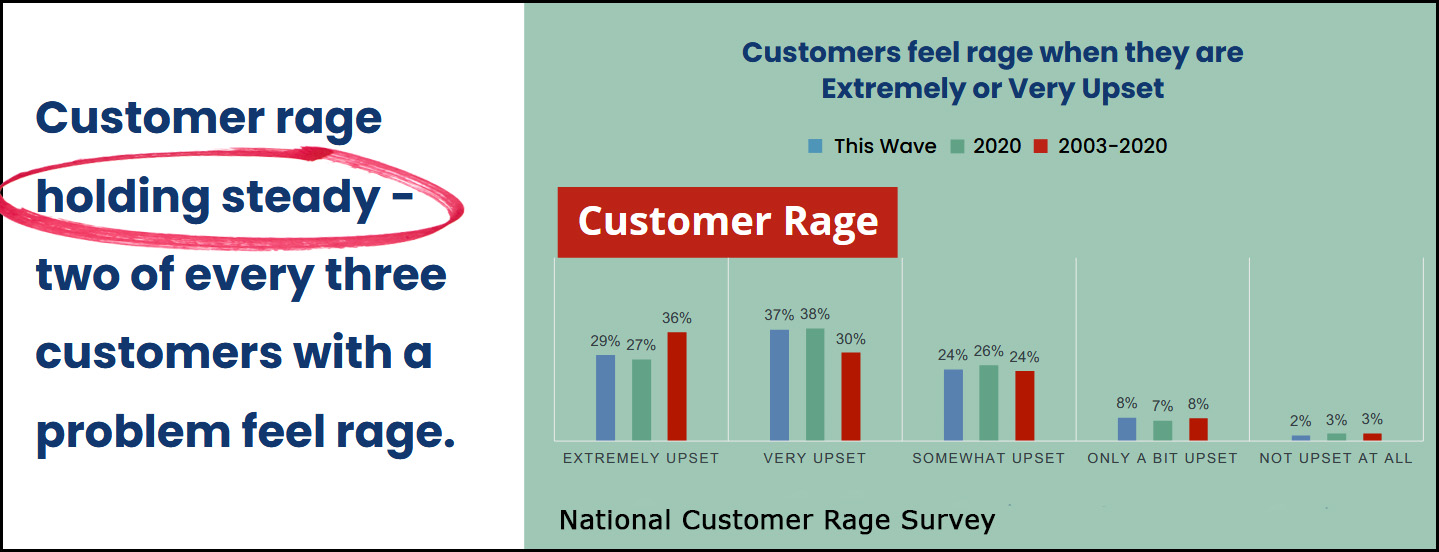

And here, believe it or not, are a couple of results from the annual Customer Rage Survey, conducted by Customer Care Measurement & Consulting and Arizona State University:

The number of people reporting that they get "extremely" or "very" upset at things was 66% in 2003 and 66% in 2022. There's also this:

The number of people reporting that they get "extremely" or "very" upset at things was 66% in 2003 and 66% in 2022. There's also this:

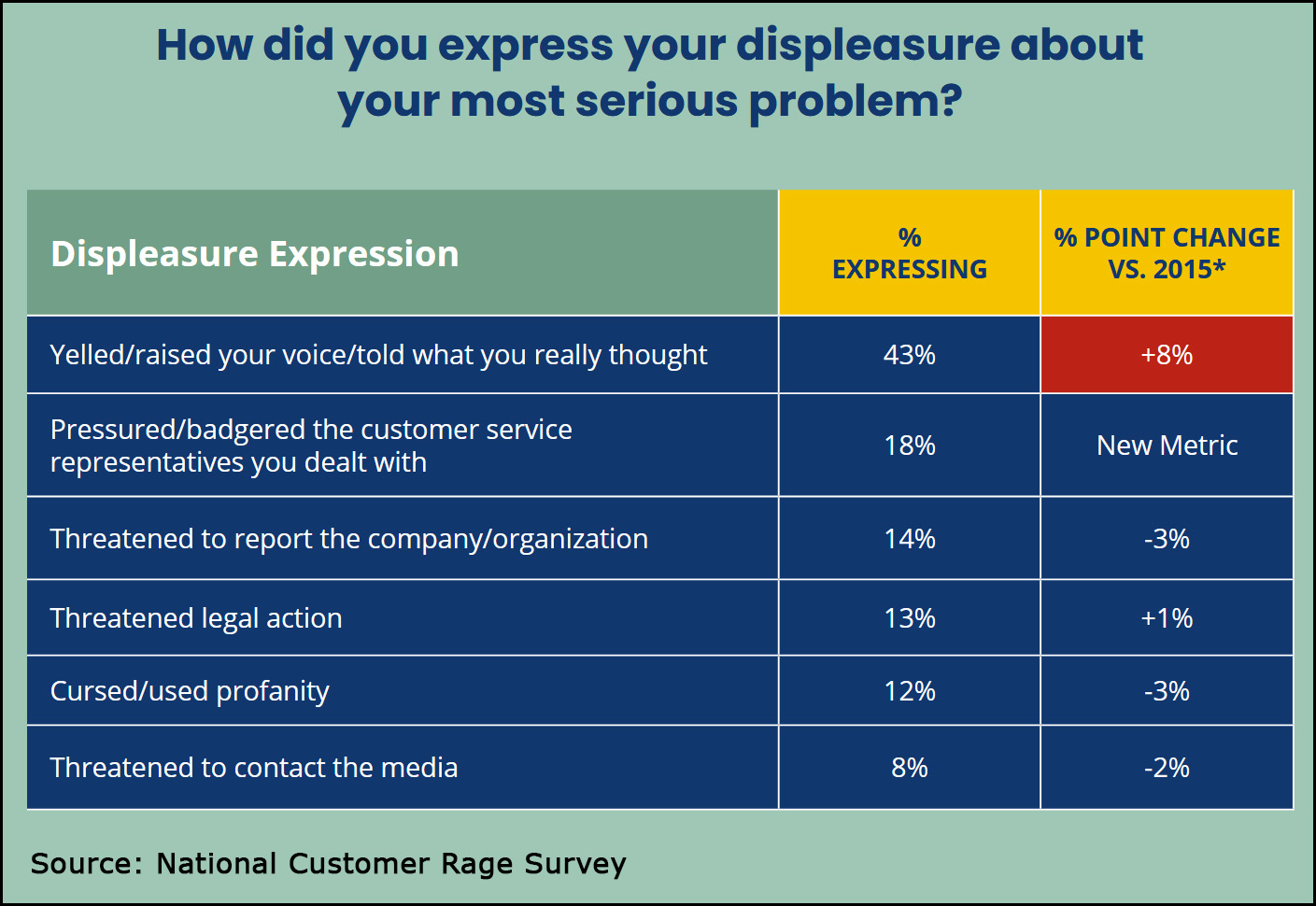

Compared to 2015, more people raised their voice when they were mad, but on every other metric bad behavior was down.

Compared to 2015, more people raised their voice when they were mad, but on every other metric bad behavior was down.

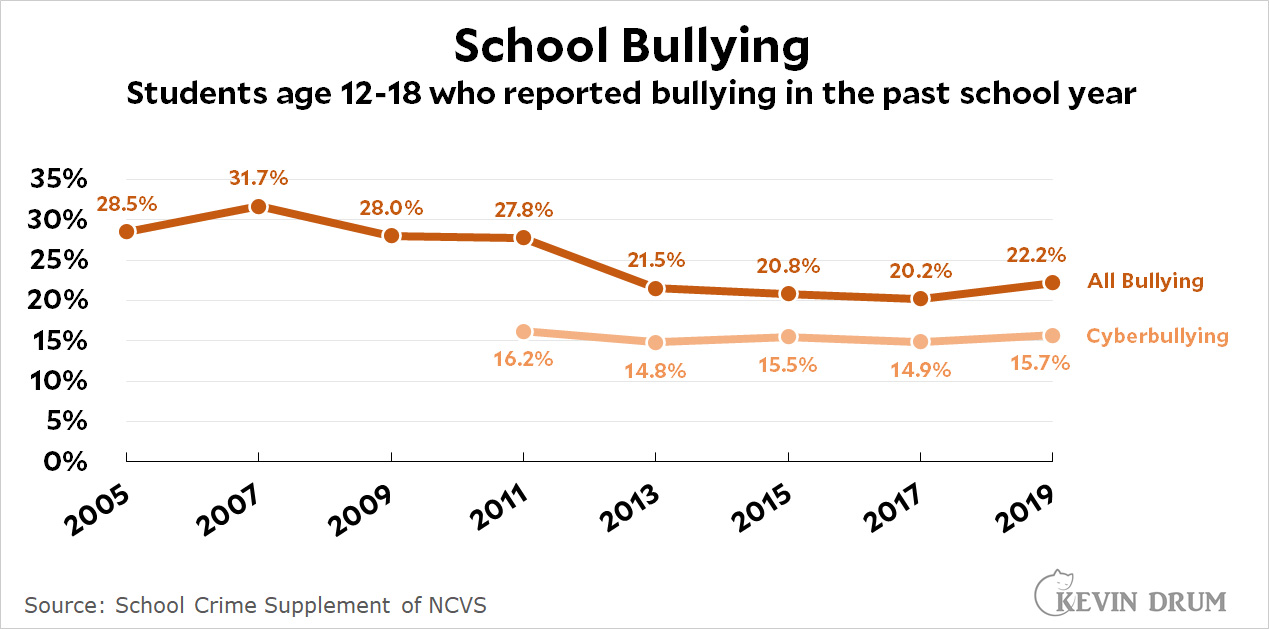

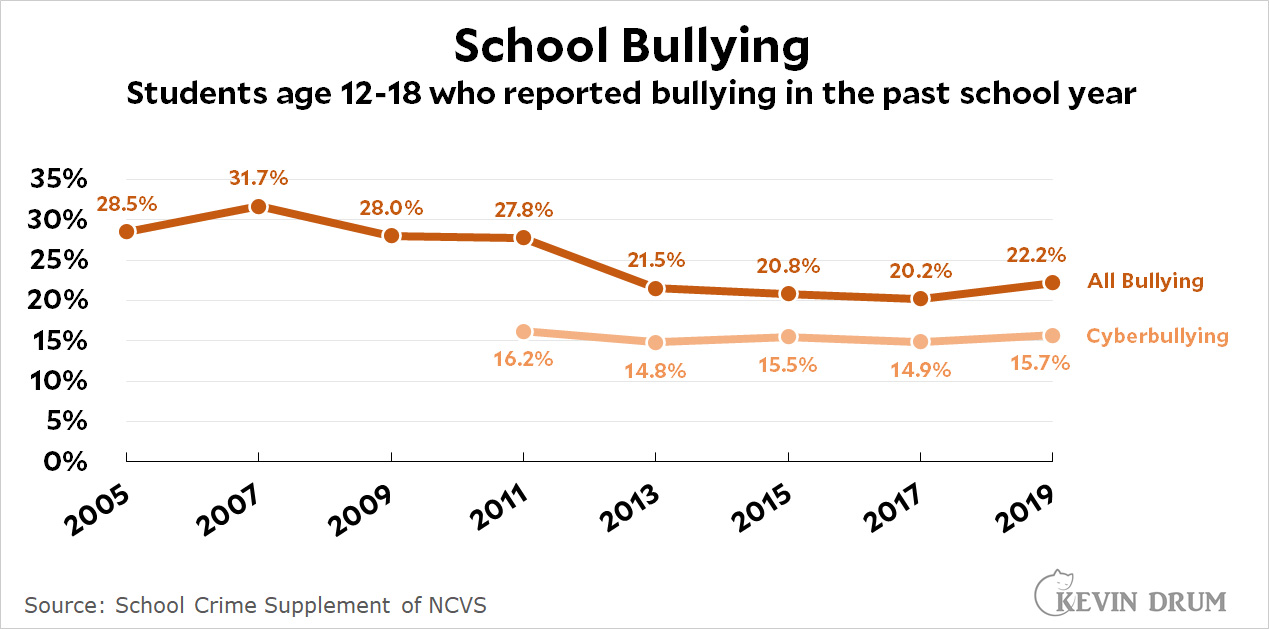

Here is school bullying:

None of this stuff is proof positive of anything. For one thing, almost all of it is self-reported, and maybe people are just kidding themselves. There's also no measure here of political polarization and anger, which has certainly increased over the past couple of decades. Still, almost all of these metrics point in the same direction: we're getting nicer, not meaner. The only exception is airline incidents, which have increased a little bit and are probably still suffering a hangover from the COVID era, when air passengers went completely bonkers.

None of this stuff is proof positive of anything. For one thing, almost all of it is self-reported, and maybe people are just kidding themselves. There's also no measure here of political polarization and anger, which has certainly increased over the past couple of decades. Still, almost all of these metrics point in the same direction: we're getting nicer, not meaner. The only exception is airline incidents, which have increased a little bit and are probably still suffering a hangover from the COVID era, when air passengers went completely bonkers.

If you can think of other examples, leave them in comments. Just remember, we're interested here in low-level rudeness and aggression, not wars or international terrorism.