Nutshell summary: Good news!

Long, complicated explanation: Buckle up for this one. No doctors were involved in this analysis.

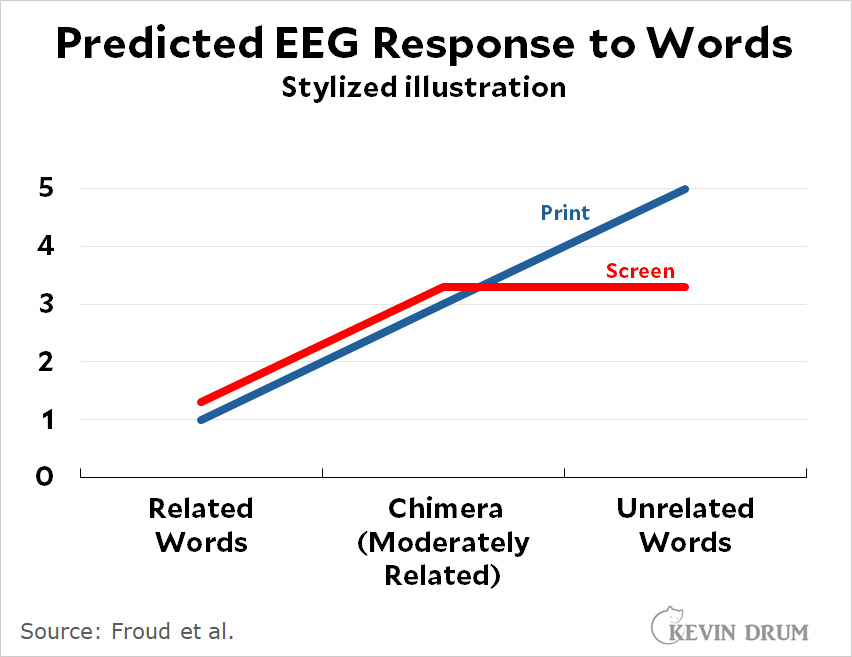

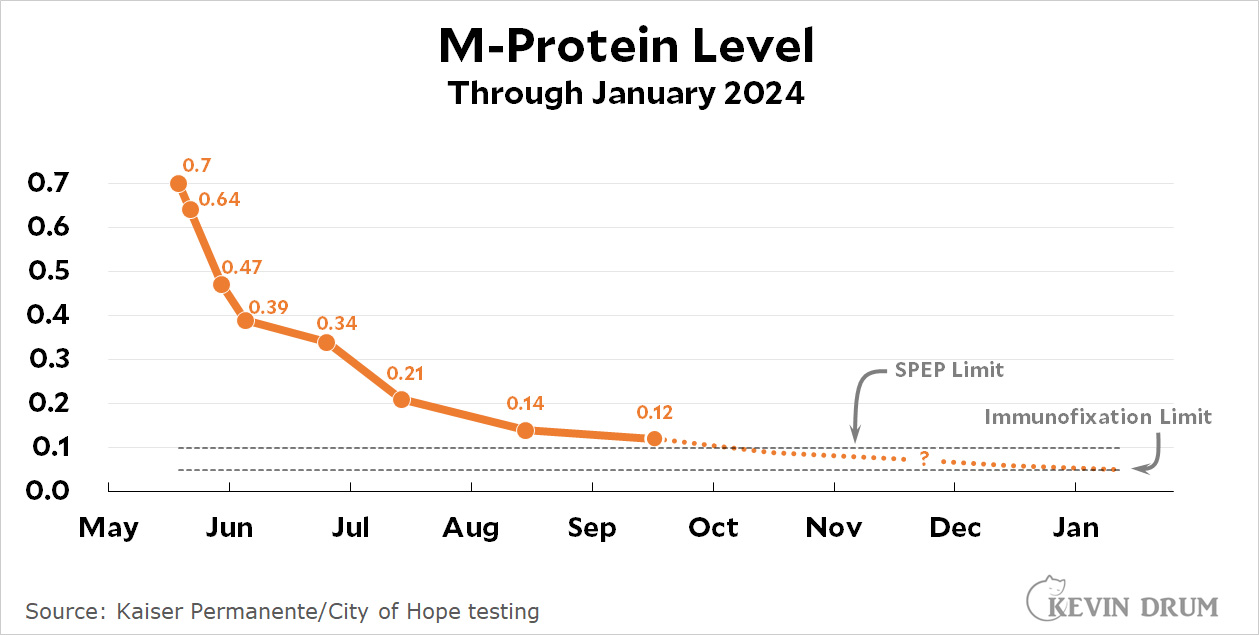

As you know, for years I've been getting M-protein results to check the level of multiple myeloma in my bone marrow. This is done via an SPEP test—Serum Protein Electrophoresis. A successful treatment of my cancer would mean that the M-protein level was "undetectable." Not completely gone, but so low the SPEP test couldn't detect it.

I always assumed this meant an SPEP result of 0. But no: I finally got tired of never getting an explanation of how this stuff really works so I looked up the clinical literature myself. In the relevant units, it turns out that SPEP can only detect M-protein down to about 0.10.

But there's more. I've also been getting a second test all along: Serum Immunofixation. It's a binary test (normal/abnormal) so I've never paid any attention to it. Obviously I've been abnormal ever since I was diagnosed.

Not anymore. It turns out that immunofixation is only accurate down to a level of about 0.05. Below that the cancer level is undetectable.

Now, as you might recall, the CAR-T procedure I had last April can produce a range of outcomes. The best outcome is "complete," which turns out to mean a cancer level that's undetectable by both SPEP and immunofixation. Conversely, if you're below the SPEP level but still above the immunofixation level, your outcome is "partial complete."

That's where my test results have been for months. But this month something changed in the immunofixation results. Instead of "IgG Kappa monoclonal gammopathy"—i.e., multiple myeloma—the result was "Band of restricted mobility of IgG Kappa. Consider retesting if clinically indicated." This suggests that the immunofixation result is right on the edge of being undetectable. Here's a chart:

September was the last time I got an SPEP result. Now, in January, I seem to be very near to not getting an immunofixation result either. If this is true, it means I've finally reached the fabled "complete" response from the CAR-T procedure. It took eight months instead of six weeks, but in the end it came through.

September was the last time I got an SPEP result. Now, in January, I seem to be very near to not getting an immunofixation result either. If this is true, it means I've finally reached the fabled "complete" response from the CAR-T procedure. It took eight months instead of six weeks, but in the end it came through.

Now, it's worth noting that no doctor has confirmed this for me. In the case of my general oncologist I think it's because he's not familiar enough with CAR-T to know these details. In the case of my transplant physician, I imagine he knows but just never felt like explaining in detail.

So that's that. It's good news no matter what, and if my amateur interpretation is correct it's very good news. The next step would be a test for MRD—Minimal Residual Disease—which is more sensitive than either SPEP or immunofixation. No one has suggested this yet, probably because I was nowhere near needing it before now. Maybe someday.

In any case, who knows? The fact that it took so damn long to reach this level might mean it will also take a very long time before it starts to go up again. My multiple myeloma has always been fairly slow reacting. Check back with me in 2028 or so and we'll know.