Megan McArdle picks at a scab of mine today:

It’s hard to pick just one favorite form of internet insanity, but, if I had to, it would definitely be shoplifting denialism.

Over the last few years, shoplifting has clearly become a bigger problem. We’ve seen videos of brazen shoplifters casually walking off with goods while helpless security guards watch. Retailers tell us it’s a problem, one that’s forcing them to close some of the hardest-hit stores. If you live in one of those areas, it’s also visible in your daily shopping: the locked cases at your drugstore, the signs banning knapsacks or oversize totes, the armed guard who recently appeared at the exit of my local supermarket, checking receipts.

This is all true. Why would drugstores lock up toothpaste if shoplifting weren't a real problem? On the other hand, FBI crime statistics don't show a huge surge:

Shoplifting has gone up by a quarter since 2021, but it's still no higher than it was in 2017. However, I had to extrapolate this data myself and it might not be right. What's more, it's possible that retailers have mostly given up reporting shoplifting to the police since it does little good. Even the FBI admits that clearance rates are generally below 10%.

Shoplifting has gone up by a quarter since 2021, but it's still no higher than it was in 2017. However, I had to extrapolate this data myself and it might not be right. What's more, it's possible that retailers have mostly given up reporting shoplifting to the police since it does little good. Even the FBI admits that clearance rates are generally below 10%.

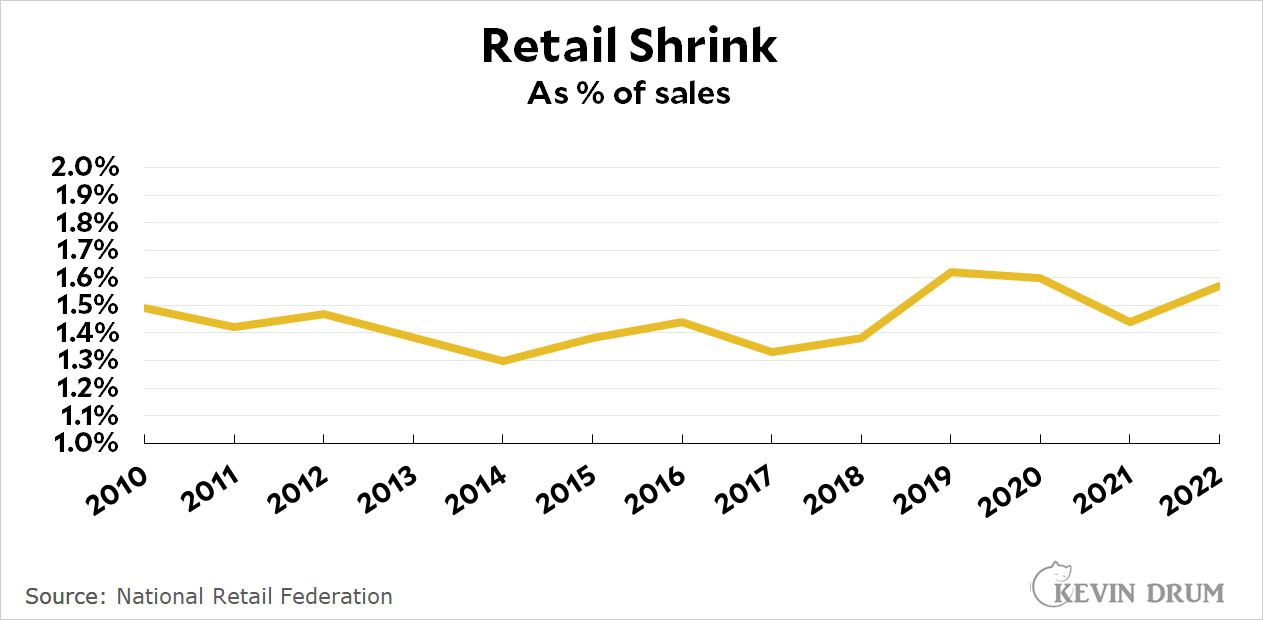

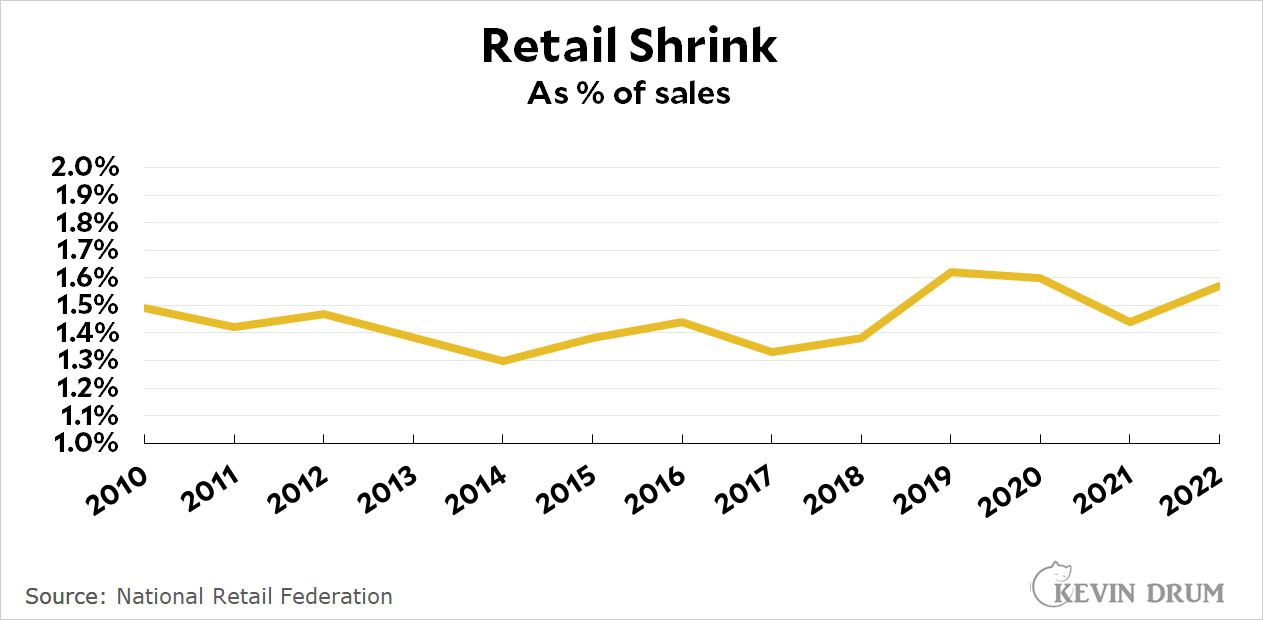

But there's also this:

This doesn't come from police reports. It comes from an annual survey of retailers by their own industry group. They have every incentive to report accurate numbers.

This doesn't come from police reports. It comes from an annual survey of retailers by their own industry group. They have every incentive to report accurate numbers.

But there are problems here too. First, "shrink" includes losses from shoplifting, employee theft, and operational errors. Maybe it's steady because shoplifting went up and the others went down. Who knows?

Second, maybe shoplifting really has stayed steady, but it's because of the locked cabinets, surveillance systems, and guards at the door. There's no sure way to tease out causality.

What to think? It sometimes happens that widespread anecdotal evidence flatly doesn't match the best statistical data. This is one of those cases. So what's the best bet: trust the statistics or trust the anecdotes?

The case for statistics is that they really do tend to be reliable on a nationwide basis. The case for anecdotes is that they can identify trends faster and at a more granular level.

The case against statistics is that they're bloodless and don't always capture the full scope of things. The case against anecdotes is that media coverage can amplify limited local events into broad moral panics that don't represent reality. In turn, this can motivate businesses announcing weak results to blame everything on the excuse du jour—in this case shoplifting—because that's better than admitting you're managing the business poorly.

This has all been a longwinded way of saying that I find this particular issue perplexing. The anecdotal evidence really does look convincing, but maybe it's only capturing isolated incidents in a few high-crime cities. And why doesn't it show up in any of the data?

I don't know.

What's more surprising is that abortion bans haven't even reduced abortions in the states where they're banned. Women in those states have either traveled out of state or obtained abortion medication. The New York Times has the data:

What's more surprising is that abortion bans haven't even reduced abortions in the states where they're banned. Women in those states have either traveled out of state or obtained abortion medication. The New York Times has the data: