I got pointed to a paper earlier today that summarized the trend in natural disasters in recent years. It wasn't super interesting, but it did have one thing that intrigued me:

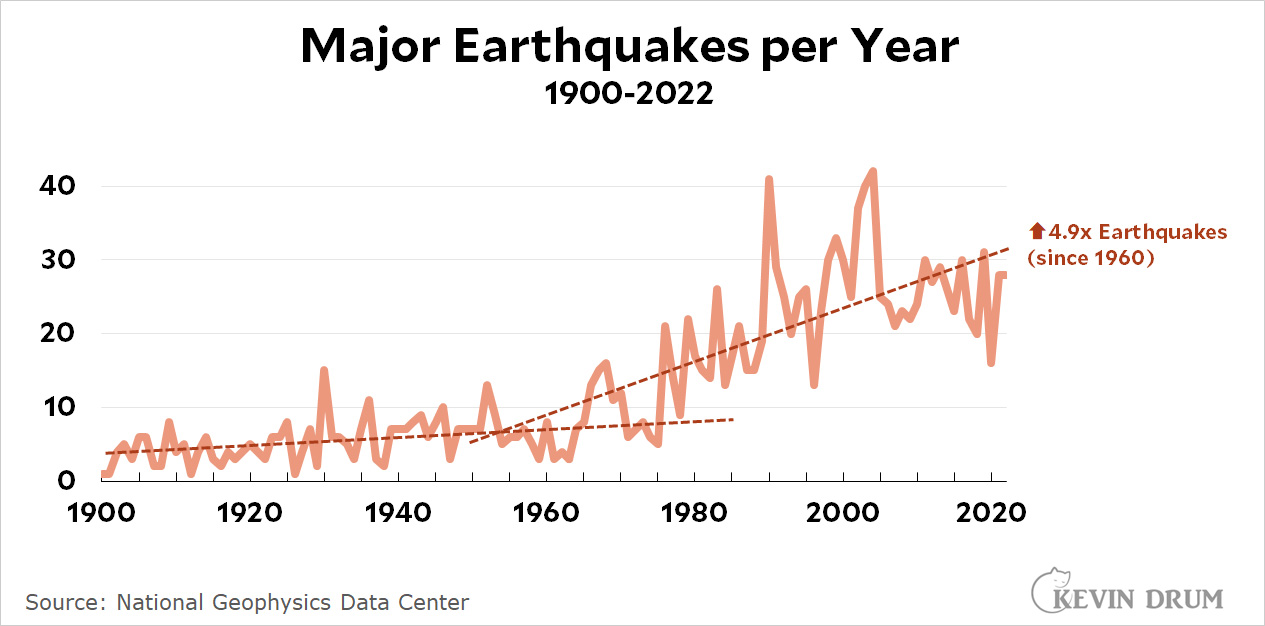

What's up with this? These are major earthquakes, so it's not likely to be a measurement issue. But for some reason the number of earthquakes suddenly took off from 1960-2000 before leveling off. We now have nearly five times as many earthquakes each year as we did in 1960 and seven times as many as 1900.

What's up with this? These are major earthquakes, so it's not likely to be a measurement issue. But for some reason the number of earthquakes suddenly took off from 1960-2000 before leveling off. We now have nearly five times as many earthquakes each year as we did in 1960 and seven times as many as 1900.

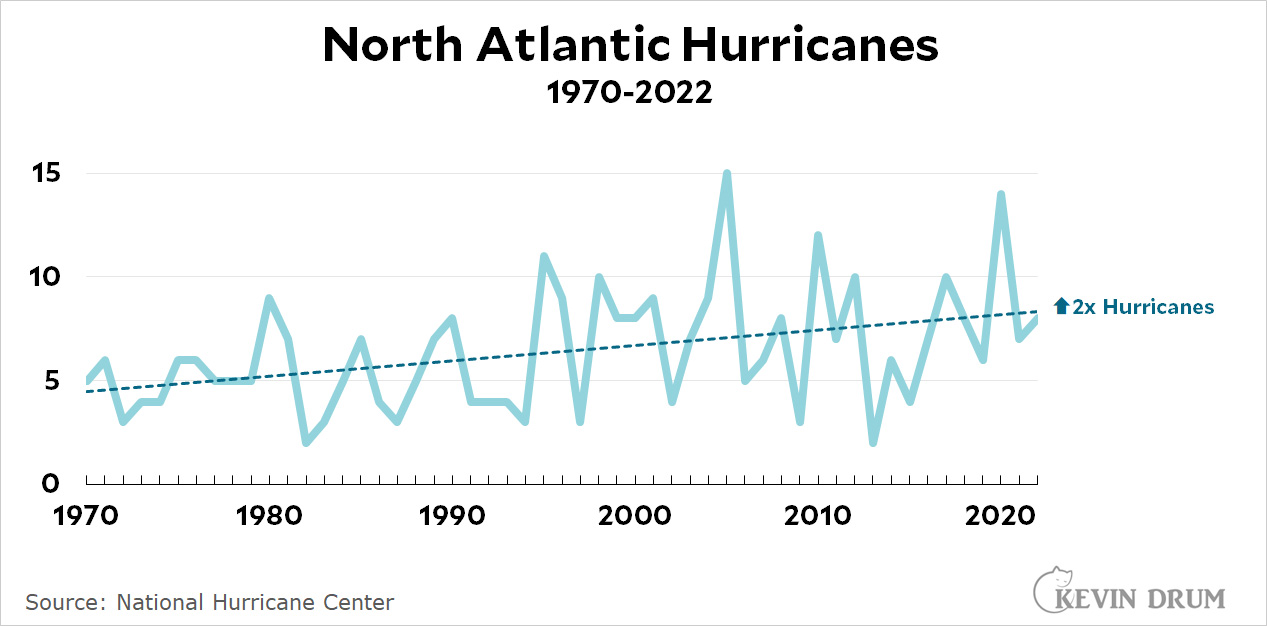

Anyway, as long as I was doing this, I checked out hurricanes too:

North Atlantic hurricanes are up about two times since 1970. Here's everything else climate related:

North Atlantic hurricanes are up about two times since 1970. Here's everything else climate related:

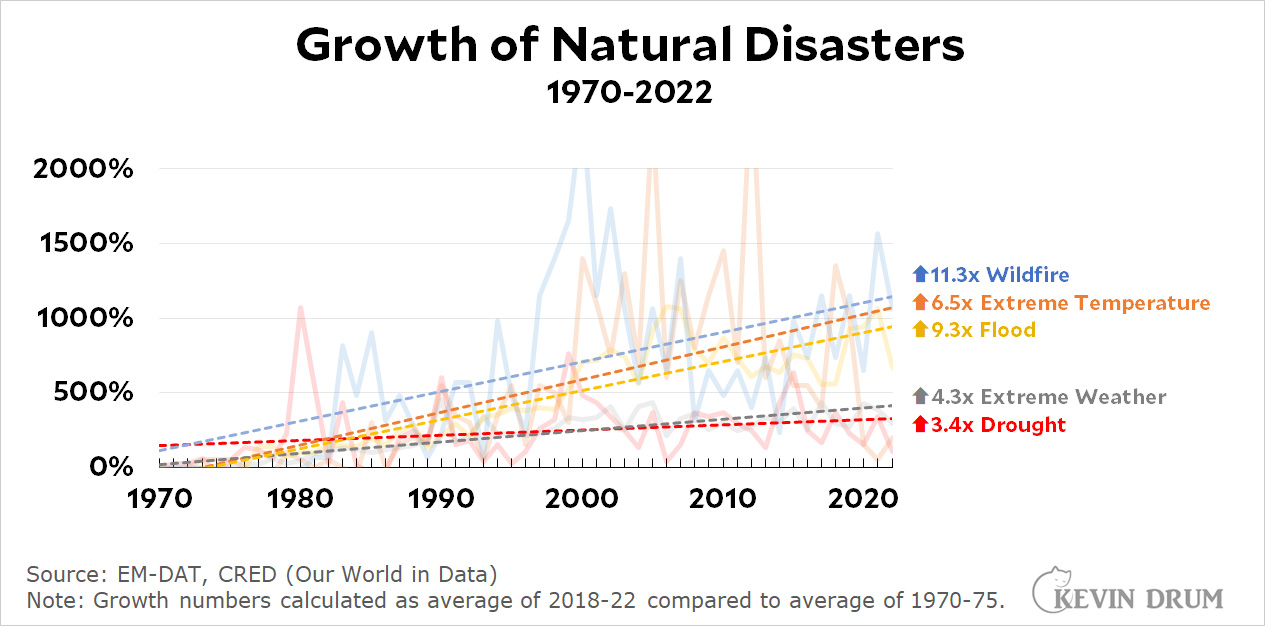

Everything climate related is up a lot since 1970. No surprise there.

Everything climate related is up a lot since 1970. No surprise there.

But what's the deal with earthquakes?

Inflation!

Not a geologist. But there is some evidence that the reduction of ice or lakes has reduced the slippage of faults. The "Big One" has not hit California. The Salton Sea is shrinking.

Not sure the Saltin Sea “counts” in so far as it was a man-made accident.

The theory is the weight on the Salton Sea puts pressure on the San Andreas fault at the southern end of California. Man made or not has nothing to do with it. It is the weight of the Sea that counts.

Before it was a man-made accident, it was a natural lake that dried up due to previous climate change. I got caught up in this same conundrum myself.

Actually, there's a whole slew of faults beneath the Salton Sea that were once upon a time responsible for major earthquakes. Reduction of fresh water inflow likely plays a role.

For hurricanes it's partly reporting: a hurricane has a specific windspeed definition. We've had satellite cloud photos since the 70s, so a pattern that looked like a hurricane probably would have been noted, but quite possibly not confirmed. (Of course, ships - that could measure the windspeed - would avoid them).

Wind-measuring satellites were routine by about 1990, though might not have been considered accurate enough for another decade. That would let some open-ocean hurricanes be missed.

But yeah, earthquakes, especially "major" ones, should have been detected.

Unless "major" is defined by dollar amount of damage???

The chart suggests 4.9 and higher, so force before dollars.

NM - now that I can see it on a desktop screen, that is a 4.9X assertion not a strength assertion...

As it seems Drum has not linked to underlying paper, the Earthquake definition needs clarification before one can really hypothesize, although as a first guess more broad and effective measurement from 1960s onwards would be a potential contributing factor to allow and control for.

My WAG would be lack of sensors to nail down seismic until about 60 years ago. I mean if a quake happened in the ocean before worldwide monitoring would it be noticed if too far away from land to be felt or maybe mistaken as smaller because it was far away?

For hurricanes, the real answer is that history didn't start in 1970. The 1970s was the period of lowest hurricane activity recorded. NOAA has data on hurricanes making landfall in the US going back to the 1870s, and there's no long term trend.

A hurricane which does not make landfall is still a hurricane.

I've put the numbers going back as far as 1900 into https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ngW7b4rUz7fZfx1SXZwhdpKLuoxvx1FjXgneH1Ii51s/edit?usp=sharing The "data" tab. Feel free to make a copy and take it back to the 1870s to prove your assertion. Going back as far as 1900 at least there is very definitely a trend in the data.

Oh, and it shows that the 1970s were not the period of lowest hurricane activity recorded. If you want to shift the goal-posts to hurricanes world-wide, please provide a followable reference. This site does permit links in comments, you just have to start with actual text first.

Thanks for that - I'm always eager to learn. Where did your counts come from? Why do you think you have comprehensive data for the number of hurricanes before 1970? I'd always heard that hurricanes that didn't make landfall were reported by ships, but ships tried to avoid the hurricane belt because of the hazards of encountering hurricanes.

I think that the scientists writing for the IPCC took my view - they note an increase in number of storms since 1970, while noting that NOAA's data is reliable and shows no trend since 1900. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-11/

References are in the spreadsheet in the "Notes" tab.

From your reference:

OK - but what does that have to do with the number of hurricanes? My question was "Why do you think you have comprehensive data for the number of hurricanes before 1970?" Your reference is to Wikipedia, which refers to HURDAT, the Hurricane Databases managed by the National Hurricane Center. This database was originally established to record the tracks of hurricanes at the request of NASA to understand risks to space launches at Cape Kennedy. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HURDAT) I've read several papers from the relevant offices (https://web.archive.org/web/20150402114424/http://www.nws.noaa.gov/oh/hdsc/Technical_papers/TP36.pdf, https://web.archive.org/web/20161221020658/http://www.nws.noaa.gov/oh/hdsc/Technical_papers/TP55.pdf, https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/NHC_Past_Present_Future_1990.pdf). They discuss in detail how they determine hurricane tracks. Over time, they've expanded the dataset to include hurricanes going back to 1851, where the data is available.

The key question is "How much data is available?" Prior to 1970, there were two basic ways that hurricanes were detected: when they made landfall, or when they were encountered by ships at sea. As I noted, ships tended to avoid hurricane areas during hurricane season, so it's very likely that some storms were missed. Since 1970, we've had satellite systems in place that can identify storms, and probably catch every storm as it develops. So, prior to 1970, the best available data is a subset of all storms. If you're interested in hurricane tracks, especially hurricane tracks that affect land, you have pretty good data. If you're interested in the number of storms that made landfall, you've got pretty good data, particularly for the US. If you're trying to count all the storms each year, you've got good data only back to 1970.

Well, looking at the chart, 1970 appears to have been 5. The trend-line for "today" (through 2022) is at 8. 1.6X is a funny definition of "two times" ...

The trendline went from about 4 to about 8, which fits the standard definition of doubling.

"About 4" to "about 8" might be "about doubling" but is not "doubling" and that trend line is not "about 4" - the actual counts are whole numbers, so while Kevin did not give us minor ticks/lines, we can see where they are (in the middle of those lines) and the trend line is more than half-way up from four.

And, interestingly enough, while I was trying to find Kevin's source (which I still seek), I came across: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1970_Atlantic_hurricane_season which asserts there were 7 hurricanes (echoed in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantic_hurricane_season) and https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/mwreview/1970.pdf which asserts there were only three.

That's ... odd. Thanks for the info, this definitely bears looking into.

I went ahead and transcribed Kevin’s numbers and those from Wikipedia into a spreadsheet. Apart from two years in the 1970s they agree: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ngW7b4rUz7fZfx1SXZwhdpKLuoxvx1FjXgneH1Ii51s/edit

Would be nice to see Kevin’s source.

I owe you one, sir.

No worries, the proofreading will be worth it.

Fracking?

I was thinking that at first, but I noticed it’s major earthquakes, I think fracking causes lots of small earthquakes, like literally more than 1 a day in Oklahoma, but very few if any of them are major.

Was thinking the same thing. Hydraulic fracking took off in the early 60s, so who knows... maybe it causes more serious seismic problems in some places than the industry is letting on?

Fracing, in the modern sense, took off around 1990 not thwe 60s, It was invented in the 60s but very small scale and uncommon until the 90s.

OK, next chart peeve - "4.9X since 1960" - perhaps, if one cherry picks 1960 from one trend line and today from the other. The trend line running to "today" has 1960 at perhaps 9.5, but we'll call that 9. And 31 for today. 3.4X. Which should be a plenty big and scary enough number on its own.

Here's my guess. Things tend to expand as they get hotter. The same would be true of the earth's crust. As the plates expand, they push up against each other more than they would otherwise.

Warming is a surface and atmospheric phenomenon. It hasn't increased temperatures at the depths at which earthquakes take place.

Far more likely is that melting ice sheets have decreased downward pressures on the earth's crust, causing it to shift.

Actually, (some) geologists claim that the el nino signal can be read off of the changes in the rate of spin of Earth's inner core. And if changes in el nino weather pattern can be traced back to temperature changes in the Earth's atmosphere ...

One should be advised before such guesses to do a small bit of self-education on plate tectonics and fundamental energies involved (as well as geological heat factors, with a side reading perhaps on geothermal). This may have some small chance of eliminating making nonsensical guesses.

Oh, but we enjoy speculative guessing! As long as we don't get married to some foolishness, (eg Republicans) it is all good...thinking actually, It could be wrong, but thinking it is. On the heating question I initially saw a cracked hard boiled egg....the shell all akembo...well, whatever. Traveller

As the Earth is not like a boiled egg physically - as boiled eggs do not have internals under such pressure that mineral solids heat to liquification - the analogy is literally worthless.

Of course glacial melting will have effects via relief of weight and thus rebound, they will be showing up in the upcoming decades - consider for reflection, Scandinavian rock is still rebounding from a glaciation that ended over 10k years ago.

I seem to recall that continental drift---the theory that eventually became plate tectonics---was initially scoffed at as a nonsensical guess. So be careful. Scientific history is littered with so-called experts insisting that various speculations could not possibly be true, only to look like fools later on when evidence comes in that proves the experts wrong.

Plate tectonics was scoffed at until DATA, which became available with more advanced instruments, demonstrated

However this is fucking irrelevant to the subject of a degree celsius in atmospheric warming being imagined to influence plate tectonics which involve deep earth temperatures that literally liquify rock (although also water cycle at super-heated state under pressure).

Yellowstone e.g. ...

The energies and orders of magnitude of forces are not comparable.

That is scientific illiteracy of the Hollywood disaster movie sort.

Wondering about this at mere human decades scale is nonsense. Emmerich disaster movie nonsense.

Climate change has already enough actual real negative effects without adding illiterate disaster movie pseudo-science.

Here's a thought with no supporting evidence: I would guess that the dawn of the atomic age resulted in greatly expanded spending on networks of much more sensitive seismographs so we could watch for other countries' tests. If true, you can squint at the graph and assume the technology got as good as it needed to be by around 1990. There aren't more major earthquakes, we just detect them all.

Improvement in global detection technology & coverage certainly as a measurement factor certainly needs to be controlled for - as the earthquake increase is one rather difficult to associate with human factors excepting more thorough and extensive monitoring technology coverage.

It's much simpler than that: If you look where the two trendlines cross it is exactly on my birthday: I must be to blame. Sorry!

Could less load from glaciers in the Andes and Alaska affect earthquakes there? Or from Greenland and Antarctica affect them worldwide? There is this phenomenon of rebound, where the crust rises after an Ice Age. The East Coast is still rising, actually.

The east coast is not noted for its numerous earthquakes, though. They are a lot more likely to happen at plate boundaries, which don't exist there.

The decrease in pressure from melting ice sheets causes shifts within the earth's crust, so it can affect areas far away from Greenland and Antarctica. And Iceland is extremely volcanically active.

Charleston 1886, an intraplace earthquake around 100 fatalities. Lower risk but not NO risk and a higher risk of damage due to the lack of building codes to make buildings safer during quakes. See the 2011 quake centered in Louisa County VA - millions in damage to the National Cathedral in DC and the Washington Monument on the National Mall.

I think that the increase is likely a measurement issue. The number of earthquakes detected each year continues to rise as detection improves. Depending on how “major earthquake” is defined, it seems quite plausible that there were many undetected ones. (Remember that about 71% of the earth's surface is covered by ocean.)

Source: http://cires1.colorado.edu/~bilham/Honshu2011/Satake%20and%20Atwater.pdf

This, and what SC-Dem says, seem right to me. I can recall how novel the 1964 Alaska quake was, and that what really set it apart was that photographers were able to get up there for Life and other magazine coverage and display just how dramatic its results were.

Think how many really major quakes would have happened in earthquake-prone parts of the world before contemporary instrumentation or before photographers could be there to capture them at just the right time. And think how routinely skeptical our "civilized world" was about reports from areas that had a lot of quakes.

Changes in underground water flows, glacial and ice sheet melting, all undoubtedly have and will have major effects, and we know that injection wells have produced a lot of small shallow disturbances. But in geologic time I have to think most of these changes are so recent that their effects won't be felt for a very, very long time. Subterranean water could be a big exception, maybe, for its effects on fault lubrication. But isn't it the case that Canadian shield country is still thought to be rising since the last Ice Age cover melted?

"But isn't it the case that Canadian shield country is still thought to be rising since the last Ice Age cover melted?"

Yes, but it also has one of the lowest incidences of earthquakes world-wide. The whole thing is moving up in unison. No plate boundaries to stick when they need to slide.

The entire continental reach of last extensive ice age glaciation, northern North America of which the N-NE of the USA and Canada, and Europe, of which notably Scandinavia / Baltic sea basin are not just 'thought' to be still rebounding but are without doubt.

Geological time makes nonsense of human time.

See: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/16/climate-change-triggers-earthquakes-tsunamis-volcanoes

If you think about it, fracking has caused a rise in earthquakes in Oklahoma. It seems quite likely that, by humans raising global temperatures, the knock-on effects include events that raise/lower pressures acting on large plates or sections of plates that then push faults to relieve stresses.

No, no it does not seem likely in the least, rather it's innumeracy that makes that seem likely. The geological factors acting on the plates respond to temperatures and pressures far beyond the trivial factors of humanity's current reach. (mixing fracking with plate tectonics rather indicates no grasp of the geology of either, nor the entirely different forces and magnitudes involved).

Small earthquakes and factors raised in the article are quite another order of phenomena.

In short, human-centrics get over yourselves.

Climate impact is quite severe enough on ecosystems humans need - the stres on humans need - without going Emmerich drama fantasy à la "2012"

Did you read the article?

I read the Guardian opinion piece, yes. It was about as useful as one would expect a Guardian opinion piece in this area to be.

Then, you would understand the potential parallel of small scale pressure changes from fracking acting on localized small scale geological features contributing to small earthquake clusters in Oklahoma with large scale pressure changes acting on larger scale geological features eventually resulting in larger earthquakes.

NOAA:

But if the scale (pressure) and frequency of such events increase, then it should follow that the number of earthquakes will increase. Now, is that the only thing contributing to an increase in earthquakes? No. But if large pressure changes are contributing to "slow earthquakes", then it also is likely that such massive, persistent pressure drops/increases such as heat domes and the Arctic polar vortex are also having an effect.

.... none of that is likely in the least and is sheer bollocks on the timescale Drum is looking at.

Of course the mystery of the increase has been clarified to be in fact MEASUREMENT as rational and modestly informed respondents immediately sai.

Yeah, I bet it's a measurement problem anyway. Even if they're major quakes, if you don't have detectors that will detect the quake in an obscure part of the world (to us, in the West), or in the ocean, you're not going to count it.

But to monitor nuclear explosions, we've been improving detector technology across the years in question. And yes, probably by now the tech is good enough to spot any major quake anywhere, and so the rate has leveled off.

I'd be surprised if fracking had anything to do with it. We could probably answer this question with a map that showed where quakes were detected in the 1900s vs today.

Tectonic or post-glacial rebound. Put a block of ice on a trampoline, it creates a dimple in the fabric. As this block of ice melts, the trampoline slowly rebounds toward it's original state. On a planetary scale, the diminishing ice sheets in the polar regions are causing tectonic activity everywhere else. Large-scale flooding can also cause an increase in tectonic activity. Water can lubricate a fault zone that is close to giving way. This may have happened with the rain in So Cal last week.

Rain fall does not lubricate fault planes or cause earthquakes. Earthquukes general start kilometers below surface. Water at those depths has been there for millions of years.

I agree with what others have pointed out: the "rise" in earthquakes is almost certainly due to the creation of a global network of sensitive seismographs in the 50s and 60s used to detect nuclear detonations and enforce test limitation and test ban treaties.

As an old, barely qualified (BSc) geologist I have two comments. First, I thinks seismographs were good enough and widespread enough to reliably identify major earthquakes well before 1960. To identify nuclear test they needed to identify and locate much smaller earthquakes. Second, there may be a medium term (decades long) natural variation in earthquke frequency that we are now seeing (we don't have long enough records to know). Climate change may also have an effect but aremore likelyto cause smaller earthquakes. One other note; for any specific fault, fearthquake frequency is highly vriable. It maty average 50 years but could easily go from 25 to 125 years.

Could you please link to the paper? My guess is that their “major earthquake” threshold is by damage, not intensity, so the trend is a reflection of GDP

There were apparently seismographs before the end of the 19th century, but I wonder whether they had the coverage and sensitivity to measure events all over the world as early as 1900, when the graph starts. We need to know whether the frequencies are based on seismograph evidence or historical reports of damage.

Major earthquakes can be detected all around the world. The modern network of very sensitive seismographs can dectect smaller earthquakes and locate any earthquake much more accurately (including there depth) but older seismographs could detect major earthquakes.

The United States Geological Survey has commented on major earthquake frequency without noting any trend since 1900:

"In the past 40-50 years, our records show that we have exceeded the long-term average number of major earthquakes about a dozen times."

This is a remarkably uninformative statement. Why shouldn't the number be greater than average over many of the 40-50 years? It is not possible for the number to be less than the average every year unless the frequency is decreasing.

I agree that sentence says little. It does underscore to me that they didn't have any recent increase in the numbers of major earthquakes to speak of.

For what it's worth, the USGS count of major earthquakes (meaning magnitude 7.0 or above) from 1900 through 2021 has 11 years where the number of major earthquakes exceeds the long term average of 16 per year, 5 years where it equals the long term average, and 16 years where the number of major earthquakes is less than the long term average.

https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/lists-maps-and-statistics

A linear regression shows the number of major earthquakes decreasing at a rate of 0.026 earthquakes per year over that period. That's probably statistically insignificant. A linear regression over the period 1990 through 2000 shows a slope of zero, which doesn't support Drum's contention that the number of major earthquakes was increasing between 1960 and 2000.

The increase in earthquakes parallels the growth of obesity epidemic, just sayin.'

There is some research that suggests that ice shelf / glaciers slowed down the movement of tectonic plates, and their loss/degredation is leading to more earthquakes.

https://worldcrunch.com/green/climat-change-earthquakes-connection

you're trying to compare apples to oranges KD

look at your time ranges

earthquakes over the last 122 years

hurricanes from 1970 to 2022 or 52 years

ditto natural disasters 52 years

yet, speaking glacially we've had 7 cycles of glacial expansion and contraction over the last 650,000 years. and the last ice age ended "only" 7000 years ago.

thus is where you lose a great deal of people.

The argument of human induced climate change loses itself in the time frames involved here. I would argue that we have been terrible stewards of this globe we live on and use THAT as a basis for arguing against fossil fuels use etc etc.

otherwise the human induced portion gets lost in the scales of time.

do I belive your argument(s)? Absolutely

but change it to being piss poor stewards of the globe and a LOT more people get on board.

ask yourself this.

If climate change were to stop getting worse for the next thousand years would we pat ourselves on the back claiming we had "won" the battle or would we call it the abnormal few centuries?

most people don't grasp the concept of a 100,000 year time frame

the dangers are real. the time frames are too different

Yeah, but what is the REAL horror of climate change?

https://www.mattball.org/2023/08/the-horror-of-climate-change.html

If you google earthquakes and climate change you will get your answer. A basic amount of work friend.

Pingback: Here’s why we have more earthquakes – Kevin Drum