I've mentioned several times that the Fed's aggressive interest rate hikes haven't yet had an effect on inflation, which has been declining on its own. The reason is that it takes time for the impulse of an interest rate hike to work its way into the economy and produce an impulse in the inflation rate.

But on average, how long does this take? Fifty years ago Milton Friedman popularized the idea of "long and variable lags," which suggests we don't really know for sure. But there's been a ton of research about this since then, which means we can at least hazard a guess or two. This will take a while, so buckle in.

Our first problem is that a great deal of the research looks at how long it takes interest rate changes to have their greatest effect on inflation. The most common guess is 18-36 months. This is suggestive that interest rates have very little impact in their first year, but no more than that. What we really want is research that tells us how long it takes for an interest rate hike to have a noticeable effect on inflation.

Here are a few comments on that:

- Esther George, Kansas City Fed President: "We don't know exactly. I think typically, we've thought about 6 to 12 months of lag in that."

- Nate DiCamillo, Quartz economic reporter: "Part of the reason why the Fed’s rate hikes haven’t had more of an effect is that they take about six to nine months to work their way through the economy."

- Raphael Bostic, President of the Atlanta Fed: "A large body of research tells us it can take 18 months to two years or more for tighter monetary policy to materially affect inflation."

- James Cloyne, then of the Bank of England, and Patrick Hürtgen of Germany’s Bundesbank: "In the U.K., a 1 percentage-point increase in the policy rate reduces output by 0.6% and inflation by up to 1 percentage point after two to three years."

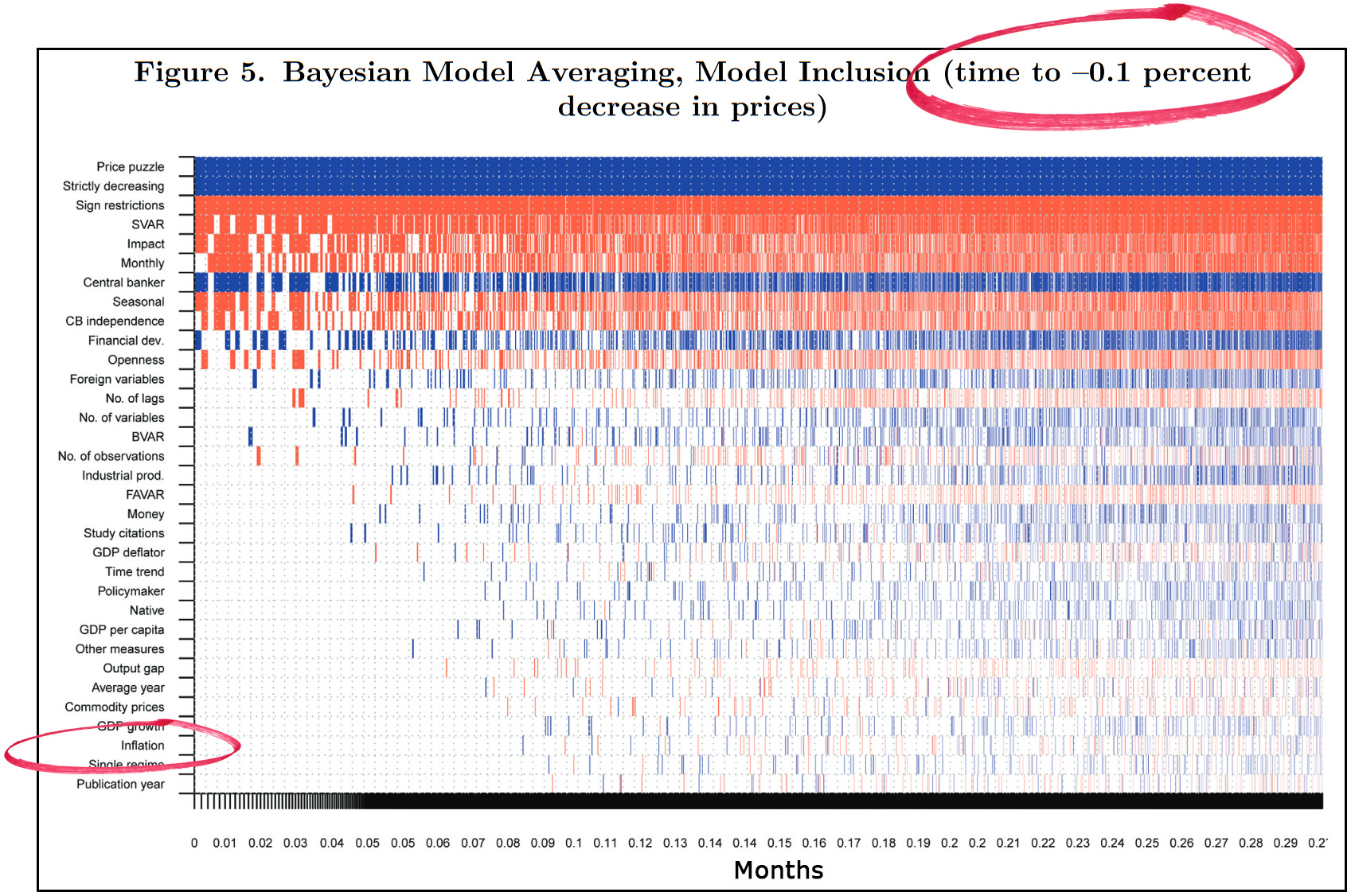

Taken together, these suggest that interest rate hikes start to have an effect on inflation in about a year or so. But I have one more study to add to this, and it's the most interesting of all. It's a meta-study from Tomas Havranek and Marek Rusnak of the Czech central bank and it examines research about monetary policy changes in dozens of countries over the past few decades. It suggests that the maximum impact of rate hikes takes 3-4 years to materialize in the US. But now take a look at something else. First I'm going to show you the whole chart even though it's illegible at this size:

For now, just take a look at the two things I've circled. First, this is a measure of how long it takes for a rate hike of 1% to produce an inflation response of -0.1%. In other words, how long it takes before you get the first hint of lower inflation.

For now, just take a look at the two things I've circled. First, this is a measure of how long it takes for a rate hike of 1% to produce an inflation response of -0.1%. In other words, how long it takes before you get the first hint of lower inflation.

Second, look at the lower circle. Out of all the things that monetary policy affects, inflation is the very last. Inflation reacts very slowly to rate hikes.

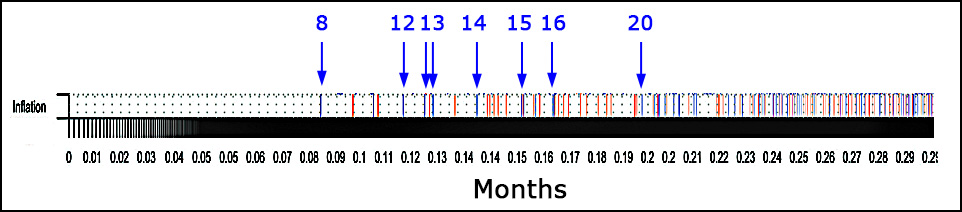

Now let's zoom in on inflation and see what it says:

This is still not the most legible graph in the world, but it does the job. The blue lines represent monetary episodes that produced a positive response—that is, where a rate hike produced the expected reduction in inflation. The earliest response was 8 months and every other episode took at least 12 months to have an effect on inflation.

This is still not the most legible graph in the world, but it does the job. The blue lines represent monetary episodes that produced a positive response—that is, where a rate hike produced the expected reduction in inflation. The earliest response was 8 months and every other episode took at least 12 months to have an effect on inflation.

Bottom line: Except in the most extraordinary circumstances, rate hikes take around nine months to have an effect, and 15 months is probably more likely.

In our current case this doesn't really matter. The earliest date for serious Fed hikes is May 2022 and nine months takes us out to February 2023. It's an almost sure thing that the Fed's actions have had no effect on inflation yet, and probably won't for another three months—maybe longer.

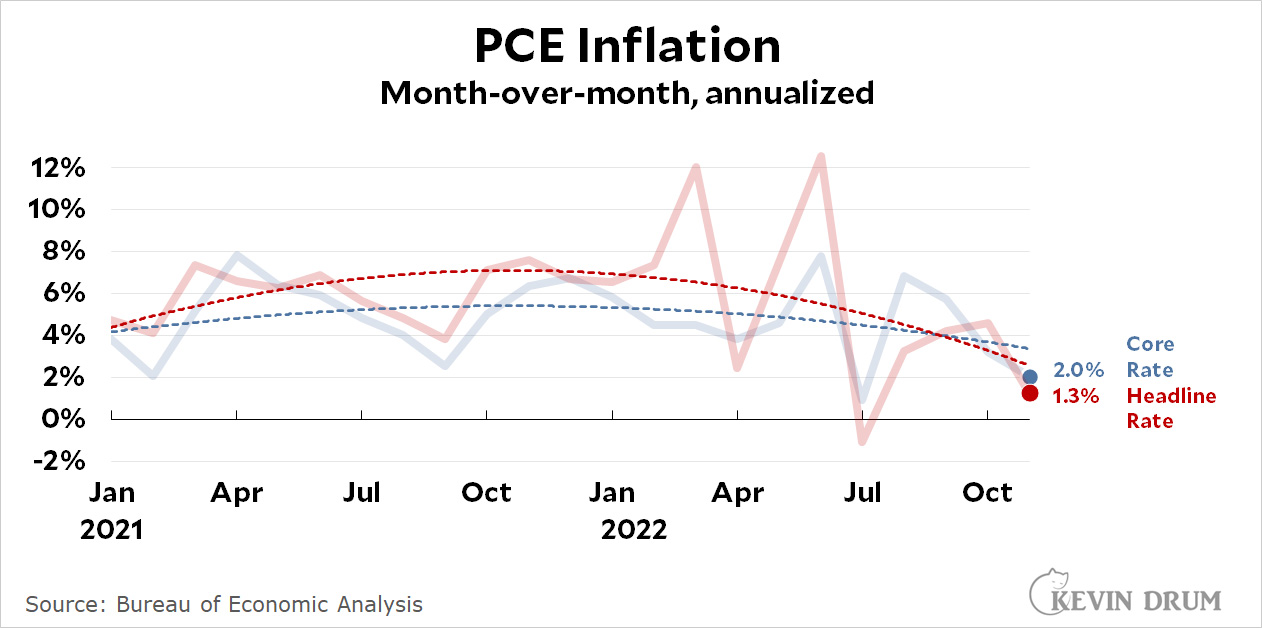

And yet, during that time core inflation has plummeted:

What caused this? My take is here (supply chain problems, stimulus, rents, and savings) but it doesn't matter much if you agree with me. The one thing we can say with high confidence is that it hasn't been the result of interest rate hikes.

What caused this? My take is here (supply chain problems, stimulus, rents, and savings) but it doesn't matter much if you agree with me. The one thing we can say with high confidence is that it hasn't been the result of interest rate hikes.

However, interest rate hikes generally affect economic growth sooner than they affect inflation. In fact, low economic growth is one of the channels used by rate hikes to influence inflation. So there's a good chance that the Fed has already hurt the economy and will continue to hurt it even worse next year, all the while affecting the inflation rate—which had already come down by itself—only much later, when we no longer care about it.

Worst. Fed. Ever.

From the other thread

"The Fed most likely had nothing to do with it."

After writing something akin really to an anti-vax conspiracy theorist with only a vague understanding of the subject on hand and misunderstanding and misframing actual subject experts general comments....

Sad really. Very sad. Ergogan levels of sad.

He’s becoming almost unreadable. It really is quite sad. I’ve been following Kevin for something like 15 years, but this drivel is pushing me away.

You missed the revised GDP, yesterday? Q3 third estimate was 3.2%, up from 2.9% in second estimate, up from 2.6% in initial estimate. Exciting times to be contrarian macro. NAIRU is completely vertical. Phillips Curve is broken.

The Phillips curve was broken in the 70's and the NAIRU has never worked. Many economist never learn from experience - they elaborate on excuses as to why the Fed's assumed control of inflation (and the economy) never actually works.

Biden has a responsibility to publicly criticize the Fed for their actions that will result in a recession on his watch.

Certain factors can be identified as causing recent inflation; the rise of oil price, supply problems, rents, and some other things associated with the pandemic. When these factors subsided, a reduction of inflation was predictable. The Fed's actions had nothing to do most of with these factors. Some people went wrong in forecasting the subsidence of those factors too early or in minimizing their effects, but the subsidence has actually taken place now, and inflation has actually gone done (it has been low since July). There is no need to bring in an effect of the Fed's interest-rate actions to explain either the rise or the fall of inflation.

The main canon of the standard dogma on inflation is that unemployment is the key - falling unemployment causes inflation and the Fed brings inflation to an end by raising unemployment. The Fed has not raised unemployment yet, although its actions may do so after inflation has already been going down for some time (which has happened before). The supposed experts have continually got this and other assumed causes of inflation wrong.

The Federal Reserve Board has only one thought and one purpose, and that is to create a labor surplus. The fact that they did not act to do this during 2020 and 2021 only indicates that they felt that they had no effective tools. Now they do, but, like everyone, they are fighting the last war: their tools, which are the old ones and which they only understand in old contexts, may still not work. The nightmare scenario is that they "stay the course" until the desired labor surplus emerges, by which time very great harm may have been done.

Oh and by the way, statistics aggregated across the entire country or across all industries are absolutely meaningless, and policy actions that are not narrowly targeted have no chance of success.

This feels correct. Plus, the Fed has been pretty clear that goal number 1 is weakening the labor market to keep wages down.

The Fed has explained that wage increases are bad for the economy because INFLATION!!

"Irrational exuberance" --Greenspan.

I remember when Greenspan issued that statement about the market, yet when asked about raising rates to curb enthusiasm, said that wasn't his business....

Raising rates a bit was needed, as was unwinding QEII (or whatever number it was). Not so much because of recent inflation, but because the markets were rather frothy. The initial steps will cost people money. Mortgage payments go up for homeowners and puts pressure on landlords to raise rents if they can. Same for any loan tied to Fed rates. Housing prices might come down, but that won't help people who bought when the prices were still going up.

Of course the Fed way overshot this time. We are still in a series of transitory events. There are articles about the "worker shortage" and others claiming Silicon Valley firms have hired 2 to 4x too many people. And now layoffs at big tech firms--but jobs available at other places for that talent. Those in low wage jobs are starting to see more unionization and salary increases (though not keeping up with inflation).

One of the problems we're facing is that there is far too much money in far too few hands. The covid stimulus packages addressed that to a small degree, but only a long term change in tax policies and anti-trust regulations (de-Borkify) are needed.

In the mean time, looks like Fed wants a recession. Then again, that's about all they can do--Congress has to pass immigration reform and set appropriate tax rates.

Wow, Kevin is good.

It’s not easy coming off an addiction to cheap money.

Imagine canceling Medicare, Medicaid and WIC, then scolding the country for the struggles in coming off their addiction to basic health care.

Ending public education and closing every library, then scolding people for their past addiction to cheap education.

Ending fire and emergency ambulance service, then mocking the familes at funerals for their past addiction to basic safety services.

etc....

it's bizarre to see people promote less investment, lower employment, reduced economic growth and a reduced quality of life as a moral cause.

Please! Interest rates get all the press headlines but fundamentally miss the point. Yes, they will have an impact on expectations and on some limited sectors of the economy. But the real action shows up in the monetary base (MB). The Fed can just wave its hands and raise the federal funds rate, but that doesn't mean any other rate needs to increase. Rates like Treasury rates are determined in much larger markets and could move very differently from the funds rate - if market participants there had a different perspective of the supply and demand for different financial assets. If the Fed is interested in slowing the economy (or speeding it up, e.g. QE), it's going to start with reducing the MB which it started to do over a year ago in late 2021. So the Fed has actually been undertaking contractionary policy for over a year.

Second important point. Friedman noted "long and variable lags" and the emphasis generally has been on the "long" part. There is absolutely no reason to think that the lagged impact of Fed actions after the Great Recession should look the same as the lagged impact of Fed actions after Covid. Add to that the fact that it is appropriate to treat the lags in both cases as distributed lags, which Kevin suggests. That is, there will be some impact almost immediately, generally building over time, and then presumably gradually waning as (1) inflation slows and (2) the Fed deflationary actions also slow, albeit with the expectation that (1) follows (2).

There has been a huge amount of research on this subject but trying to put it together in a meta-analysis is simply a fools game. You simply cannot combine observations across countries and even making comparisons within a country has two major limitations. (1) We really don't have many observations of inflationary periods, and (2) the causes of inflation will differ across periods and controlling them is difficult if not impossible. And I have certainly tried!

I think Kevin is correct when he notes that inflation has been declining, albeit excruciatingly slowly, for months. And I think the Fed has been too aggressive in raising rates. But that's largely due to the very simple fact that our most recent recession and the current inflation are both fundamentally supply-side phenomena and the Fed actions are much more effective when addressing demand-side issues. Bottom line is we should expect a continued long slog to get the rate of price increases below 3%.

Didn’t it reduce the demand for houses financed by mortgages almost immediately?

Good effort here to shed more light on what experts might know about lagging effects of monetary policy shifts. It's hard to nail down, even if you're a Federal Reserve board member or bank CEO.

But it must be said that the horizontal scale of Figure 5 from the Czech bank's meta-study does not indicate months. It measures cumulative posterior probability of the ranked transmission lag models. To be honest, I am not crystal clear on what that means, but I'm sure it isn't a count of months. (Who would write 0.08 to mean 8 months, anyway?) The point of the figure is not to show how long the lag is, but to show which variables are most important in explaining the variability of that lag.

My buddy's mother makes fifty dollars per hour working on the computer (Personal Computer). She hasn’t had a job for a long, yet this month she earned $11,500 by working just on her computer for 9 hours every day.

Read this article for more details..