Matt Yglesias takes on the "Deaths of Despair" meme today. It originates with Anne Case and Angus Deaton, who wrote about it a few years ago, and, as Matt points out, it's somehow survived despite a series of statistical examinations that have left it in tatters. If you adjust for age, it becomes less dramatic. If you adjust for geography, it's limited largely to the South. If you break it down by education, it's largely a phenomenon of high school dropouts. Matt continues:

The rise in deaths of despair turns out to overwhelmingly be a rise in opioid overdoses. This increase is not happening in European countries that have not only been buffeted by the same broad economic trends as the United States, but are also seeing the rise of right-populist backlash politics.

The obvious explanation is that the US and Europe have very different laws governing pharmaceutical marketing....This is all actually pretty clear cut and has been said before, but critics must not be saying it clearly (or rudely) enough because the narrative just keeps trundling forward.

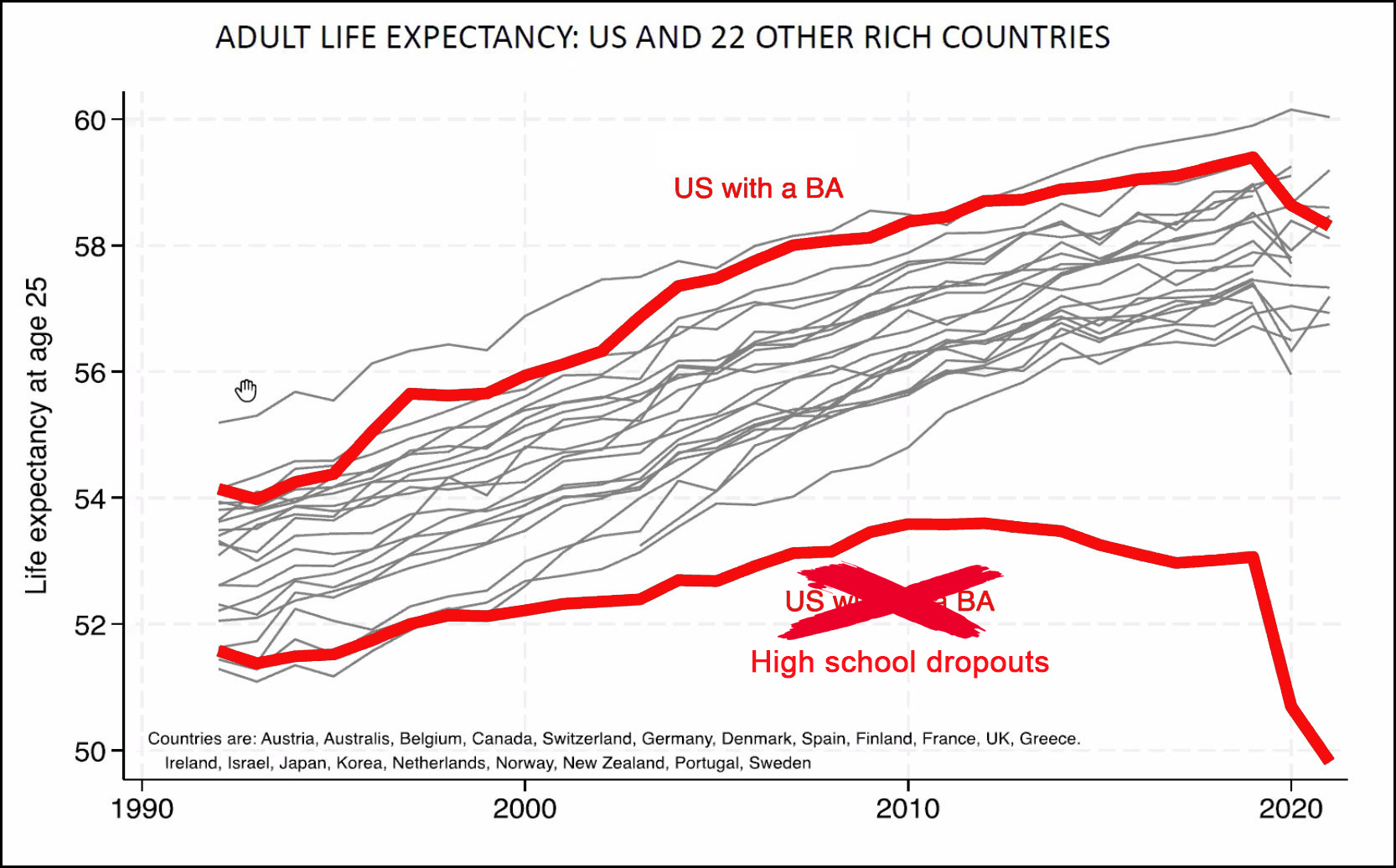

I agree with Matt's larger point: the deaths of despair narrative doesn't really seem to hold water, and it's worth saying this bluntly. But is it really just about opioid overdoses? Let's revisit a recent chart from Case and Deaton:

US life expectancy has taken a big hit compared to other rich countries, but it turns out this is largely due to reduced growth rates among high school dropouts. The slowdown started around 1998 or so, which means it has to be related to something that changed in 1998 or earlier. Something that changed more for high school dropouts than for college grads.

US life expectancy has taken a big hit compared to other rich countries, but it turns out this is largely due to reduced growth rates among high school dropouts. The slowdown started around 1998 or so, which means it has to be related to something that changed in 1998 or earlier. Something that changed more for high school dropouts than for college grads.

Now let's take a look at drug overdoses from a recent RAND study:

There's a huge difference in the rise of opioid overdoses between college grads and high school dropouts. And the OxyContin revolution started in 1996, which makes it a natural candidate for a trend that began in 1998.

There's a huge difference in the rise of opioid overdoses between college grads and high school dropouts. And the OxyContin revolution started in 1996, which makes it a natural candidate for a trend that began in 1998.

But the difference is fairly modest until around 2015, when fentanyl hits the scene. Between 2000 and 2015 the difference rose by about 30 per 100,000. Then, in just the few years from 2015 to 2021, it rose by about 45 per 100,000. Thus we'd expect life expectancy growth for high school dropouts to slow down between 2000 and 2015, and then to really slow down from 2015 to 2021.

And this is roughly what happened—until COVID hit and the bottom fell out of everything. So the only remaining question is this: Is the increase in overdose deaths among dropouts (bottom chart) enough to account for their stagnant life expectancy (top chart)? This is something that only an expert can answer. Any volunteers?