Turkey—aka Türkiye—suddenly abandoned its long opposition to Sweden joining NATO earlier today. No explanation, as near as I can tell. Very weird.

Lunchtime Photo

Please God, no more about the Luddites

Will robots take away all our jobs? Steven Rattner says no:

Almost exactly 60 years ago, Life magazine warned that the advent of automation would make “jobs go scarce” — instead, employment boomed.

Now, the launch of ChatGPT and other generative A.I. platforms has unleashed a tsunami of hyperbolic fretting, this time about the fate of white-collar workers....A breathless press has already begun chronicling the first job losses.

....[But] when it comes to the economy, including jobs, the reassuring lessons of history (albeit with a few warning signals) are inescapable. At the moment, the problem is not that we have too much technology; it’s that we have too little.

....Higher worker productivity translates into higher wages and cheaper goods, which become more purchasing power, which stimulates more consumption, which induces more production, which creates new jobs. That, essentially, is how growth has always happened.

Rattner takes us through the usual well-worn history of the abacus and the Luddites and his old handheld calculator to make his point. Sure, these things put some people out of work, but eventually new and more plentiful jobs took their place. "This is how growth has always happened."

I've just about given up trying to understand how smart people can believe this. We've had precisely one (1) genuine Industrial Revolution, and yes, it turned out fine. But why does anybody think that n=1 is predictive of every future revolution?

The Industrial Revolution mostly replaced muscle power. We still needed lots of brains to keep running things. The Digital Revolution will replace brains too. By definition, if we eventually develop true artificial intelligence it will be able to do anything a human brain can do.¹ This means, by definition again, that any new jobs created by AI can also be performed by AI better and more cheaply than people. There will be virtually nothing left for us.

How is this not obvious? Help me out here. We could, of course, address the AI revolution by flatly banning robotic labor in a wide range of situations. Or maybe we'll end up with worker riots, except putting the torch to robots instead of powered looms. Who knows?

But short of artificial solutions like that, true AI really has no plausible endpoint except mass unemployment. This will obviously require a huge rethink of how we compensate people once hourly work is out of the picture, but hourly work will indeed be out of the picture. People really need to pull their heads out of the sand on this.

¹If you don't believe true AI is possible, that's a whole different argument. It's probably not one you can win, but at least it's an argument.

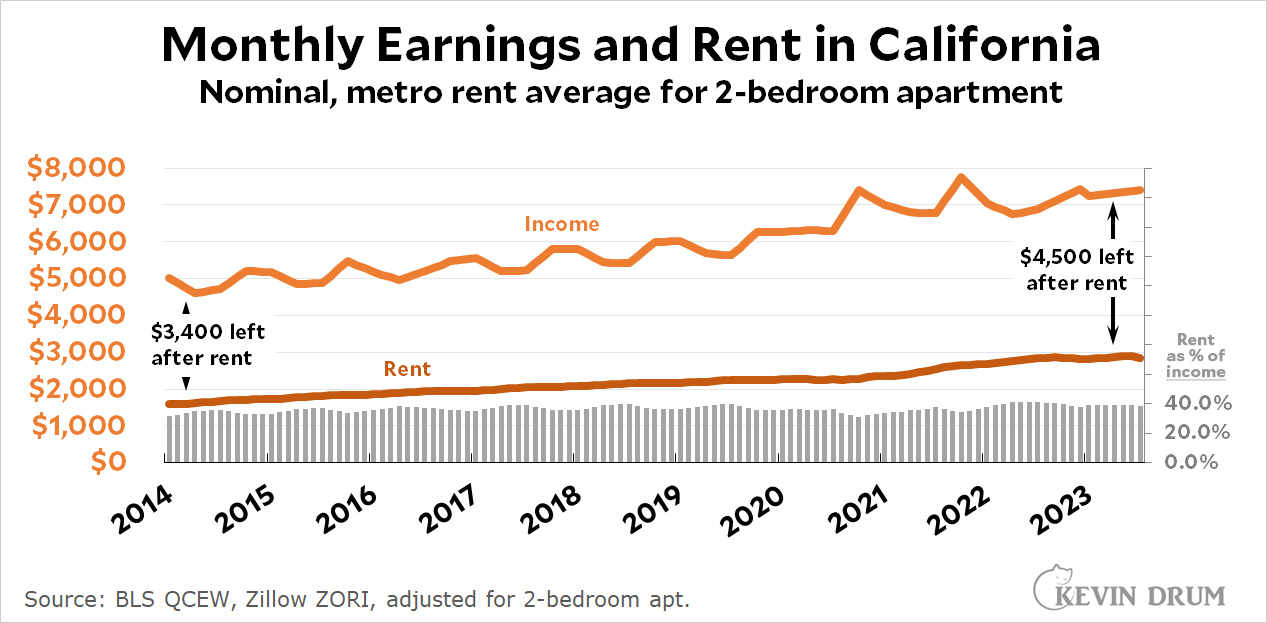

Rent in California is high, but income after rent is about the same as a decade ago

The LA Times reports that rental life is grim everywhere, but especially in California:

Minimum-wage workers shouldn't bother trying to find a two-bedroom apartment anywhere in the country.

According to a new federal report, "in no state, metropolitan area, or county in the U.S. can a worker earning the federal or prevailing state or local minimum wage afford a modest two-bedroom rental home at fair market rent by working a standard 40-hour work week."

....A California renter need to earn $42.25 an hour to afford a two-bedroom unit, the most in the nation, according to the study. The mean hourly wage for California renters is $33.67.

There's something to this. Not about the federal minimum wage, though, which currently affects only 1.2% of working adults. It's irrelevant to any serious discussion.

But rent in California is indeed very high, especially in metro areas. An average worker renting an average two-bedroom apartment in a metro area paid 32% of their monthly paycheck toward rent in 2014. Today it's more like 39%. On the other hand, there's also this:

The average worker today has $4,500 left after paying rent. Adjusted for inflation, this is about 4% higher than the $3,400 left over after paying rent a decade ago. The increase would be more if not for the overall decline in real wages over the past few years:

The average worker today has $4,500 left after paying rent. Adjusted for inflation, this is about 4% higher than the $3,400 left over after paying rent a decade ago. The increase would be more if not for the overall decline in real wages over the past few years:

California is the worst rental market in the country, but even here things haven't changed all that dramatically over the past ten years.

California is the worst rental market in the country, but even here things haven't changed all that dramatically over the past ten years.

English test set to get more rigorous in citizenship test update

The US citizenship test is due for an upgrade and apparently "some advocates" fear it will get harder. There's a bit of angst over the history section, but mainly it's about changes to the English skills section:

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services proposes that the new test updates the speaking section to assess English skills. An officer would show photos of ordinary scenarios — such as daily activities, weather or food — and ask the applicant to describe the photos.

In the current test, an officer evaluates speaking ability during the naturalization interview by asking personal questions the applicant has already answered in the naturalization paperwork.

I'm not sure why asking for a description of a picture is inherently any harder than asking personal questions. I suppose it has to do with these personal questions only requiring the applicant to parrot things they've already written elsewhere?

In any case, this sounds to me like a good change. Surprisingly, perhaps, I've never taken the increasingly popular liberal view that it's borderline racist to insist on English fluency from immigrants who want to become citizens. English proficiency is culturally critical in the United States—not to mention just plain practical—and doing our best to insist on a common language is a good thing, not a bad one.

Of course, this isn't something to get too worked up about since all the evidence in the world shows that English fluency develops strongly in second-generation immigrants and is complete by the third generation. Still, insisting on at least a decent basic level of English language competence should not be too much to ask of people who want to live in the United States forever.

Sea water near Tampa hits record-setting 90ºF

In the summer the water is always warm off the Gulf Coast of Florida. But this summer is off the charts:

"Not sure I've ever seen the water around Florida look quite like this before... at any time of year," says Brian McNoldy, the researcher at the University of Miami who created the map. The purple mass stretching from the coast off Miami, around to Cape Coral, and then up to Tampa shows that water temps there are currently over 90°F.

"Not sure I've ever seen the water around Florida look quite like this before... at any time of year," says Brian McNoldy, the researcher at the University of Miami who created the map. The purple mass stretching from the coast off Miami, around to Cape Coral, and then up to Tampa shows that water temps there are currently over 90°F.

Plus both the Arctic and Antarctic ice masses are setting record lows. And there's been yet another "1000-year" flooding in upstate New York. Those floods sure seem to occur a lot more often than every thousand years these days, don't they?

Oh, and we've just endured the hottest few days on earth in the past 100,000 years. Perhaps it's time to do something more serious about climate change than hold a few talking shops?

Air pollution doesn’t affect the birth weight of babies

Here is an interesting tidbit via Alex Tabarrok. It's a study of low birth weight in babies from Maxim Massenkoff of the Naval Postgraduate School. Here's the most basic US data:

US birth weights peaked in 1985 at about 3,350 grams (7.4 pounds) and then declined over the next 20 years to about 3,290 grams (7.2 pounds) Why? Massenkoff theorized that it might be due to small particle pollutants in the air. Here's how that turned out in several cities with high pollution levels:

US birth weights peaked in 1985 at about 3,350 grams (7.4 pounds) and then declined over the next 20 years to about 3,290 grams (7.2 pounds) Why? Massenkoff theorized that it might be due to small particle pollutants in the air. Here's how that turned out in several cities with high pollution levels:

No dice. In cities with high levels of PM2.5 particulates there was virtually no difference in low birth weight babies. But maybe US cities aren't bad enough enough to show a strong effect. Here's the same chart for some of the world's most highly polluted cities:

No dice. In cities with high levels of PM2.5 particulates there was virtually no difference in low birth weight babies. But maybe US cities aren't bad enough enough to show a strong effect. Here's the same chart for some of the world's most highly polluted cities:

Again, no dice. There's just no systematic difference between particulate air pollution and low birth weight. Massenkoff is perplexed:

Again, no dice. There's just no systematic difference between particulate air pollution and low birth weight. Massenkoff is perplexed:

In addition to the birth weight estimates in this paper, it is striking that Goldin and Margo find normal birth weights by today’s standards in a 19th century poor house. Are birth weights unusually hard to change? While far from exhaustive, I searched all reviews of randomized trials in the Cochrane Library targeting either birth weight or low birth weight. According to meta-analyses, many treatments come up short, including: zinc, calcium, deworming, vitamin E, vitamin A, vitamin C, iodine, and magnesium

On the other hand, the reviews find either increases in birth weight or decreases in low birth weight for: folic acid, vitamin D, omega-3, and anti-malarial bed nets. Also, birth outcomes within the US still vary substantially across groups: There is a stark income gradient, with mothers in the bottom income quintile more than twice as likely to have a low birth weight infant compared to mothers in the top quintile of income suggesting that access to resources could drive poor birth outcomes

So it's a mystery. The answer, of course may simply be that high levels of small-particle pollutants have lots of ill effects, but low birth weight just isn't one of them. But it's still odd.

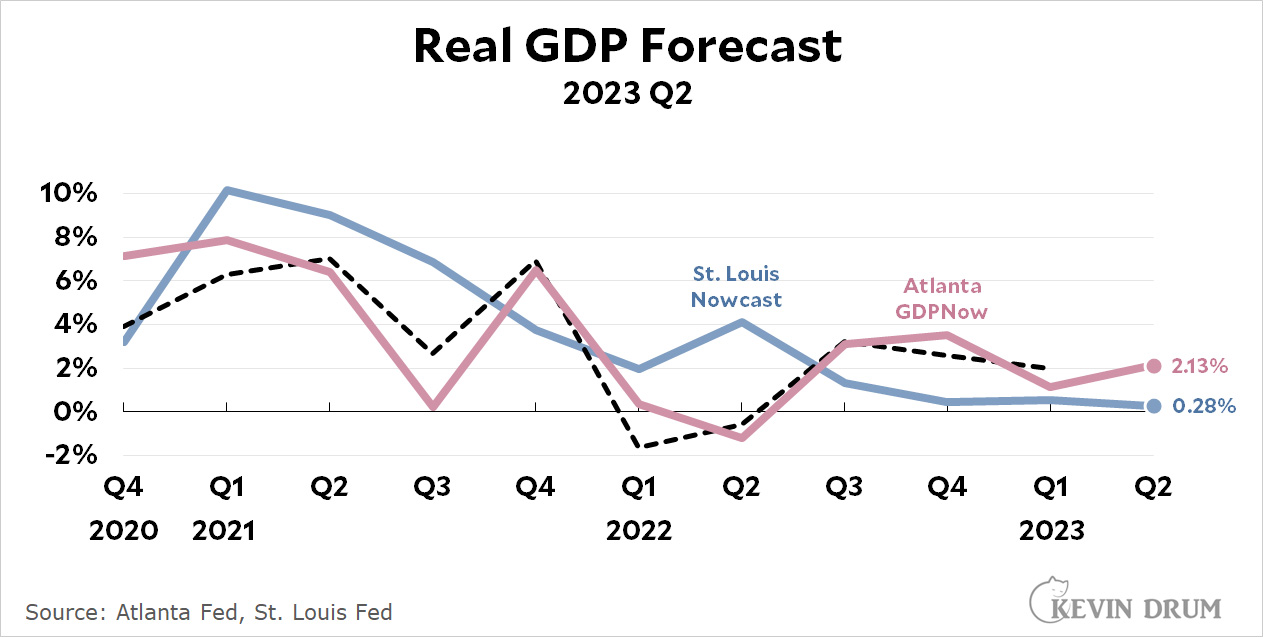

Atlanta victorious in dueling GDP forecasts

The St. Louis Fed's GDP Nowcast is forecasting that GDP growth in Q2 will be 0.28%. The Atlanta Fed's GDPNow is forecasting growth of 2.1%. Big difference! So who's right?

No offense to the St. Louis folks, but it looks like the Atlanta forecast has a considerably better recent track record. GDP growth in Q2 is likely to be OK.

Nonwhite workers are powering the economy back to work

Over at the Washington Post, Heather Long says, "If we avoid a recession, we can thank Black and Hispanic workers." I was all set to scoff, but she's right. Here's the basic employment pictire:

White workers have only barely recovered their pre-pandemic employment levels while nonwhite workers are all 10-13% higher. But a better metric of work might be the labor force participation rate, which is the percentage of the potential labor force that's actually working. Here it is:

White workers have a lower participation rate than they had before the pandemic. Nonwhite workers have 1-4% higher rates. On an absolute level, whites now have the lowest participation rate of any demographic group.

I don't really know what to make of this. Ideas?

Robocall fundraising sure is inefficient

The LA Times has a story today about a couple of fraudulent PACs that scammed both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton in 2016. The bad guys are now behind bars, but I was intrigued by this brief aside:

The two groups made more than 275 million robocalls over a 16-month period and netted nearly $4 million in small-dollar contributions.

So on average, a single robocall nets one-hundredth of a dollar. If we could just figure out a way to make phone calls cost a penny apiece, it would put the whole robocall industry out of business.