According to the Wall Street Journal, same-sex couples account for 1% of all households nationwide. Of that, half are married and a little less than half are unmarried partners. The remainder live alone or in other arrangements.

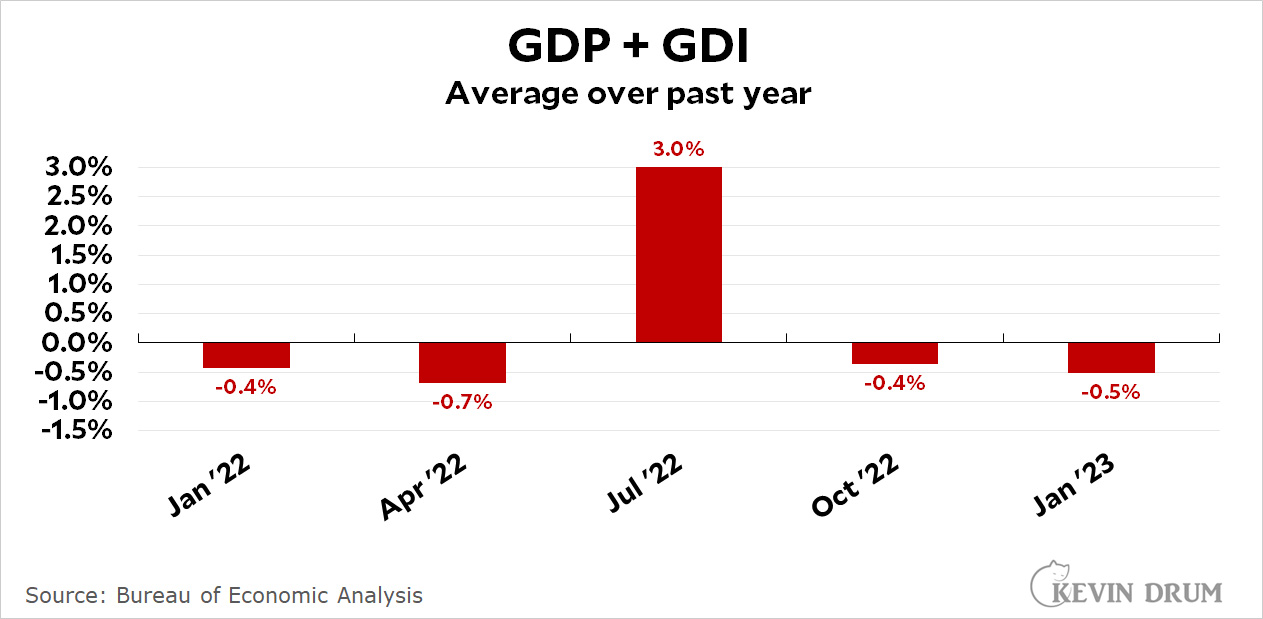

The US economy is a riddle wrapped in an enigma

The American economy is in very squirrely shape right now. I have two things to show you that demonstrate how weird things are.

First, you may recall that there are two basic measures of economic growth: GDP and GDI. They are theoretically identical, but in practice they diverge—sometimes a little, sometimes a lot. For that reason, many economists think the best overall measure of economic growth is an average of the two. Here are the latest figures for that:

If this is correct, we've been in a light recession for the past year. That hardly seems plausible, though, especially with the labor market so tight.

If this is correct, we've been in a light recession for the past year. That hardly seems plausible, though, especially with the labor market so tight.

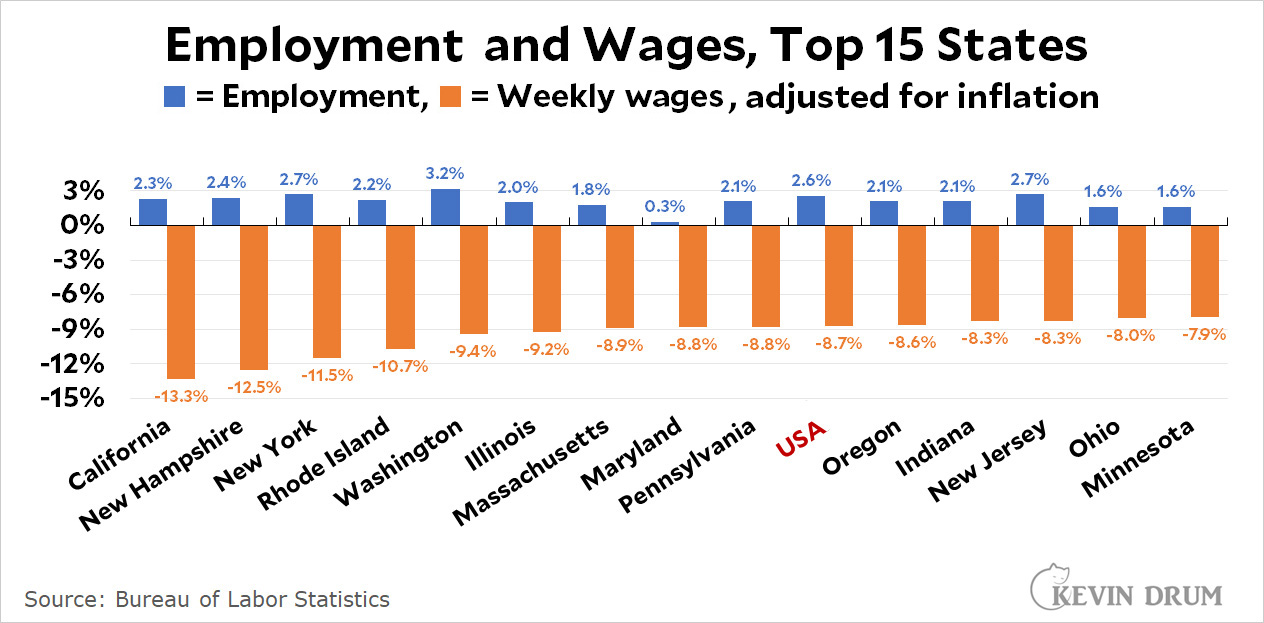

But that gets me to my second, even more astonishing chart. The BLS reported yesterday that overall US employment was up 2.6% last year but weekly wages were down 8.7% after adjusting for inflation. This same dynamic was true in virtually every state and 240 out of 355 big counties. Here's a sample:

This is nuts. Take a look at California: employment growth is strong at 2.3% but pay is down a whopping 13.3% after inflation. In San Francisco alone, employment increased 2.5% but pay cratered by 29%. How is that even possible?

This is nuts. Take a look at California: employment growth is strong at 2.3% but pay is down a whopping 13.3% after inflation. In San Francisco alone, employment increased 2.5% but pay cratered by 29%. How is that even possible?

I'm stymied by this. If hiring is strong, how can wages be going down—a lot? Is it related to the overall economy being weaker than we think? I don't know, but one way or another the labor market just isn't as tight as we think it is.

Earnings are not up

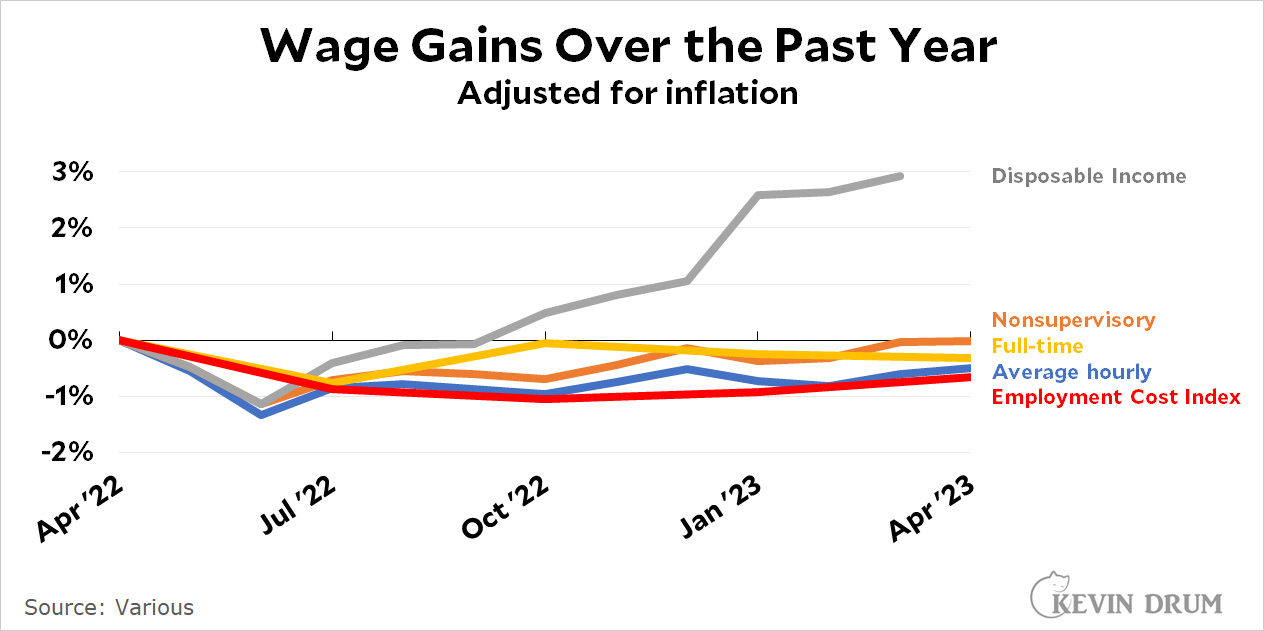

Over at the Washington Monthly, Robert Shapiro argues that Americans—and Democrats in particular—should be more aware of big wage gains over the past year. It's something to brag about.

The problem is that it really isn't true. There are several common ways of measuring wages, and nearly all of them show no gains at all over the past 12 months:

Shapiro focuses solely on disposable personal income even though every other measure shows small losses over the past year. The key here is that DPI measures income after taxes, so an increase in DPI doesn't necessarily mean that income is up. It might just mean that taxes have fallen a bit. This is almost certainly the case here, possibly due to various tax credits and temporary adjustments passed over the previous two years.

Shapiro focuses solely on disposable personal income even though every other measure shows small losses over the past year. The key here is that DPI measures income after taxes, so an increase in DPI doesn't necessarily mean that income is up. It might just mean that taxes have fallen a bit. This is almost certainly the case here, possibly due to various tax credits and temporary adjustments passed over the previous two years.

Whatever the reason, it's almost certain that income has been flat or down over the past year. There's nothing much to crow about.

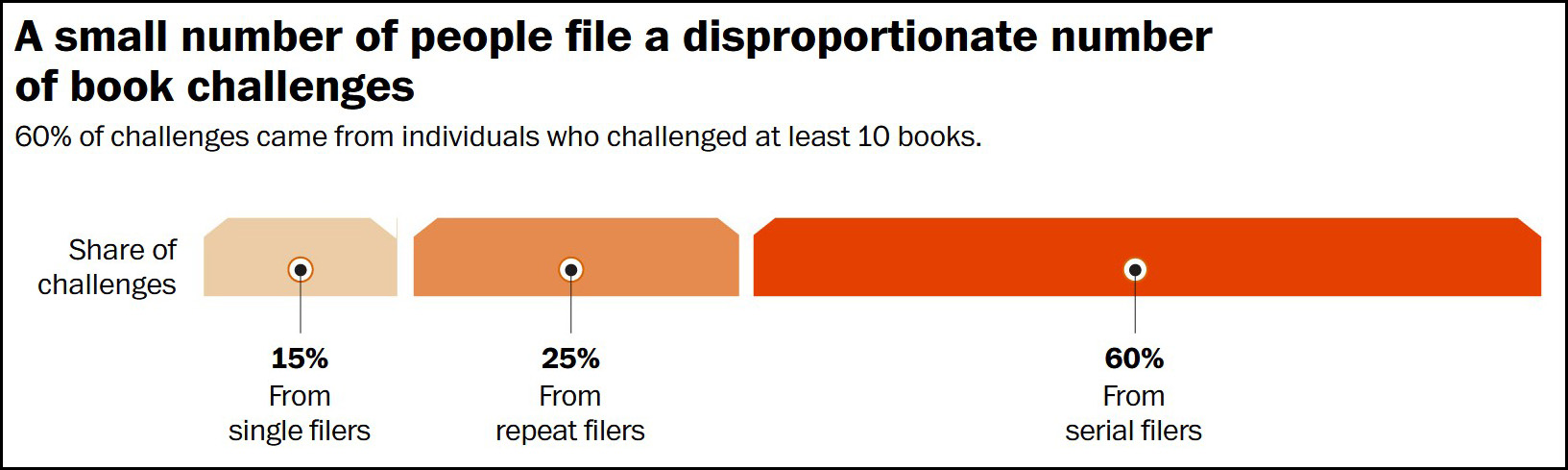

Book banning is a very, very niche activity

The Washington Post reports that most book challenges come from a tiny number of activists:

The majority of the 1,000-plus book challenges analyzed by The Post were filed by just 11 people.

Each of these people brought 10 or more challenges against books in their school district; one man filed 92 challenges. Together, these serial filers constituted 6 percent of all book challengers — but were responsible for 60 percent of all filings.

This is good news. Think about it: there's not a huge nationwide campaign to ban books from school libraries. There are literally eleven people in the whole country responsible for most challenges. And there's no telling how many of these challenges are even successful in the first place.

The fact that this is happening at all is obviously dispiriting, but it's simply not a widespread or popular activity. It's the province of a tiny handful of cranks who got way more publicity than they deserved a couple of months ago. In the end, it's a nothingburger.

Lunchtime Photo

Who gets paid if the US defaults on its debt?

One of the more mysterious aspects of the debt ceiling crisis is what happens if we actually go over the edge. There are two basic possibilities:

- Treasury simply pays bills on a first-come-first-serve basis. So if X-Day arrives on, say, June 1, and Treasury runs out of cash at 11 am, all the bills still in the queue after that would get tossed aside. This would be an entirely random set of vendors, Social Security recipients, Medicare providers, and so forth.

- Second, Treasury prioritizes payments. Maybe Social Security and bond repayments go to the top of the queue while everyone else gets (temporarily) stiffed. The problem with this approach is that Treasury secretaries have consistently warned us that our computer systems can't do it. They're set up to spit out checks when they're due, and that's that. Janet Yellen is the latest to confirm this:

Ms. Yellen declined to elaborate on how exactly she would proceed if the debt limit was not lifted, but she dismissed the idea that “prioritizing” certain payments that the government is required to make would be an easy solution. She noted that government payment systems were devised to pay bills on time, not to decide which ones to pay.

“Prioritization is not really something that is operationally feasible,” Ms. Yellen said.

This would be hellishly chaotic. Can you imagine? A bunch of Social Security recipients get their checks, but then the machine suddenly stops and the rest of the day's recipients get nothing. What happens then? Do they lose their place for a month, or are they first in line for the next day's check run? And what about bondholders? Do folks from Botswana get paid because they happen to be first in alphabetical order, while investors in the UK get defaulted?

We've never gotten to this point, so we don't know for sure what would happen. But it sure sounds like we'd all be at the mercy of a gargantuan piece of programming designed to do precisely one thing—print checks—with no discretion and no ability to stop or start except on the basis of whether there's a few dollars in the till. This works fine in ordinary times, but God only knows what it will do if Republicans shut things down. Helluva way to run a railroad.

M-Protein update

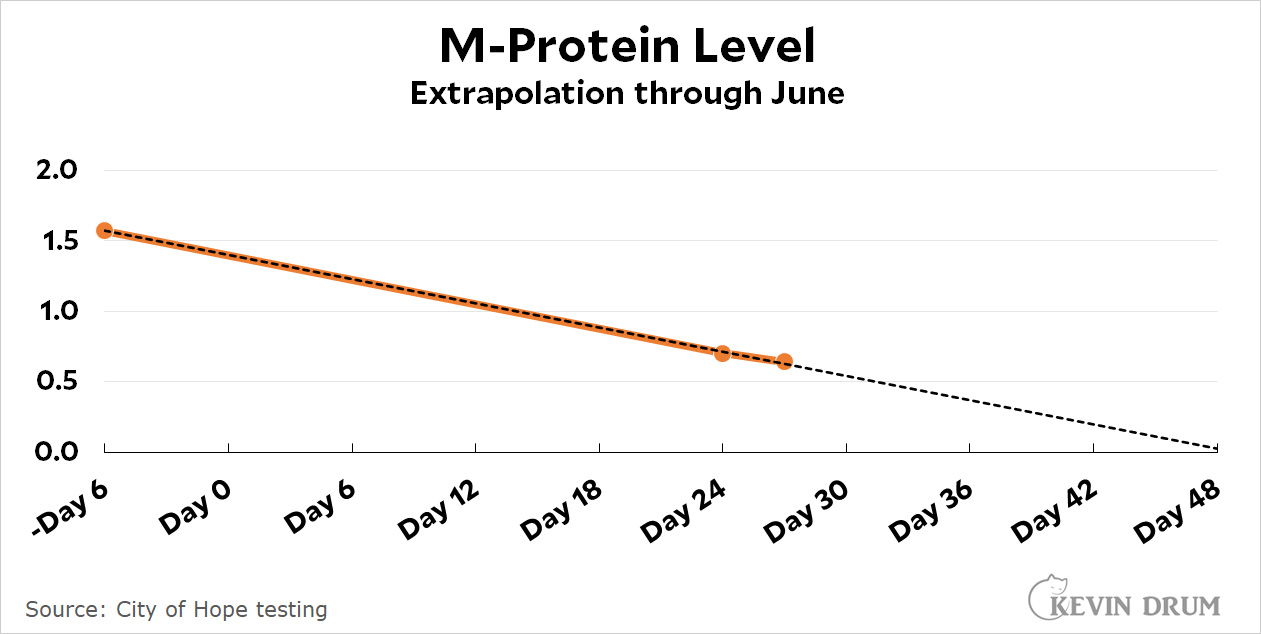

I'm feeling back up to making charts, so I thought I'd show you one that clarifies my progress with the CAR-T infusion. This is just the crudest sort of extrapolation, so take it with a grain of salt.

As it turns out, I've actually had three M-protein measurements. The first was several days before the CAR-T infusion; the second was a few days ago; and the third was on Monday. Here's what they look like:

As you can see, the M-protein level appears to be dropping on a dead straight line. If this keeps up, it will reach zero on Day 48, which is around June 12. This is seven weeks after Day 0, which is precisely when the recovery is supposed to be at its deepest.

As you can see, the M-protein level appears to be dropping on a dead straight line. If this keeps up, it will reach zero on Day 48, which is around June 12. This is seven weeks after Day 0, which is precisely when the recovery is supposed to be at its deepest.

None of this is guaranteed, and I'll have to come back for a PET scan and then a biopsy to get accurate numbers. But it does suggest that I'm on the road to zero, or "undetectable," as they call it, since the myeloma never truly goes 100% away. Regardless, it's looking good so far.

Health update

I am definitely on the mend. My counts are practically up to normal; the Bell's palsy is receding; my energy is slowly returning; and my appetite has improved. Everything is getting better.

But the bigger news is that I finally got my first M-protein result. As you'll recall, this is a proxy for the total cancer load in my bloodstream, and right before the CAR-T infusion it had risen to 1.57, the highest it had been in years. As of Monday, a month after the infusion, it clocked in at 0.64.

This is a nice drop, though I'm not sure just how nice it is. Obviously there's still a long way to go before we hit zero, which is the goal.

Lunchtime Photo

Should AI be regulated?

A few days ago, OpenAI's CEO, Sam Altman, testified that artificial intelligence posed significant dangers and ought to be regulated. Yesterday, though, he released a short brief on the subject and, remarkably, it turns out he doesn't want anything regulated at all. Not in practice, anyway. For starters, here's what he affirmatively does want regulated:

In terms of both potential upsides and downsides, superintelligence will be more powerful than other technologies humanity has had to contend with in the past....We must mitigate the risks of today’s AI technology too, but superintelligence will require special treatment and coordination.

Altman is clear that by "superintelligence" he's talking about AI considerably beyond full general intelligence—i.e., full normal human intelligence—which is generally considered ten or fifteen years away all by itself. So call it the better part of 20 years before we get seriously close to superintelligence. That's all he proposes to regulate. It's pie in the sky.

Now here's what he affirmatively doesn't want to regulate:

We think it’s important to allow companies and open-source projects to develop models below a significant capability threshold, without the kind of regulation we describe here (including burdensome mechanisms like licenses or audits).

Today’s systems will create tremendous value in the world and, while they do have risks, the level of those risks feel commensurate with other Internet technologies and society’s likely approaches seem appropriate.

In other words, all of OpenAI's current—and very profitable—work (ChatGPT and so forth) should be entirely unregulated. Only the stuff that's 20 years away deserves any attention.

This amounts to no effective regulation at all. Note that I'm not even saying Altman is wrong about this, since I have my doubts that AI will ever move slowly enough, narrowly enough, or be well-enough defined to permit any kind of effective regulation. Still, Altman is being disingenuous here. He's playing at being the reasonable man while, in practice, advocating for the Wild West.